Vocabulary Defined

‘Word’ is defined by Merriam Webster Dictionary as follows:

“1a: something that is said b plural (1 : TALK, DISCOURSE (2) : the text of a vocal musical composition c : a brief remark or conversation

2a (1) : a speech sound or series of speech sounds that symbolizes and communicates a meaning usually without being divisible into smaller units capable of independent use (2) : the entire set of linguistic forms produced by combining a single base with various inflectional elements without change in the part of speech elements b (1) : a written or printed character or combination of characters representing a spoken word

—sometimes used with the first letter of a real or pretended taboo word prefixed as an often humorous euphemism (2) : any segment of written or printed discourse ordinarily appearing between spaces or between a space and a punctuation mark c : a number of bytes processed as a unit and conveying a quantum of information in communication and computer work. (Merriam-Webster Dictionary Online, 2011, 1)

The work of George A. Miller entitled “On Knowing a Word” states that the individual who “knows a word knows much more than its meaning and pronunciation. The contexts in which a word can be used to express a particular meaning are a critical component of word knowledge. The ability to exploit context in order to determine the meaning and resolve potential ambiguities is not a unique linguistic ability, but it is dramatically illustrated in the ease with which native speakers are able to identify the intended meanings of common polysemous words.” (nd, 1)

Miller writes that it has been the fascination of many psychologists to question what it really means to ‘know’ a word and states for example Galton (1879) and his experiments with word associations and Binet (1911) testing mental age through use of word tasks. Miller also cites Ogden (1934) who selected 850 words that he deemed the individual must know to master Basic English and Buhler (1834) and his analysis of deictic words that make the acquisition of referential value from the contexts in which the words are used. Verbal-linguistic intelligence used in communicating with one another is the method that human beings use to understand one another. Verbal-linguistic communication may be either formal or informal in nature and includes such as writing a letter, creating poetry, keeping a diary, and many other such activities that are comprised of the ability of “thinking words and to use language to express and appreciate complex meanings.” (Miller, and, 1)

Verbal-linguistic intelligence is reported to be used in other activities such as storytelling, telling jokes as well as the “use of metaphors, similes and analogies…in learning proper grammar and syntax in speaking and writing.” (Wessman, nd, 1) The verbal-linguistic capabilities are primarily located in the left hemisphere of the brain and specifically in the temporal cortex area in what is known as ‘Broaca’s Area’. Included in verbal-linguistic intelligence are the following four primary sensitivity areas:

- Semantics – shades of meanings of words, whereby an individual appreciates the subtle shades of difference in descriptors;

- Phonology – the sounds, rhythm, inflection, and meter of words, which give them a kind of interactional effect on one another. It is here that how something is said is as important as what is said;

- Syntax – or the order among words, which involves the rules which govern the ordering of words in speech or writing, as well as their meaning within a particular context; and

- Praxis – the different uses of words as in sentence structure, or in understanding the cultural nuances of words, or the emotive aspects of language. Though each of these dimensions of VL intelligence can be isolated, in reality, they all function as an integrated whole. (Wessman, nd, 1)

Verbal-linguistic learning capacities include the following capacities: (1) Understanding the order and the meaning of words; (2) Convincing someone of a course of action; (3) Explaining, teaching and learning humor; (4) Memory and recall; and (5)Meta-linguistic skills. (Wessman, nd) Verbal-Linguistic Capacities Developmental Journey skill levels include the following three levels: (1) the basic skill level; (2) the complex skill level; and (3) the Coherence level. (Wessman, nd, 1)

The basic skills level “involves the acquisition and basic development of ‘building block’ language arts capacities, including simple reading and writing and rudimentary patterns of speaking” including the following: (1) Knowledge of the alphabet ; (2) Recognition of one’s own name in writing and in conversation; (3) Single word utterances; speaking pairs of words and meaningful phrases; (4) Creation of simple sentences, generally with poor syntax in speaking; and (5) Ability to perform ‘imitation writing’, especially of one’s own name and other letters. (Wessman, nd, 1)

The Complex Skill Level is reported by Wessman (nd) to involve the understanding of ‘various aspects of language as a system, for example, grammar, syntax, phonetics and praxis and the development of language comprehension skills” including the following stated skills: (1) complex and proper use of language to communicate ideas, desires, and feelings; (2) capacity to tell jokes and understand various kinds of language-based humor; (3) expanded vocabulary including skill in using new words in speaking and writing; (4) execution of self-initiated writing to communicate thoughts, opinions, feelings and so on; (5) Comprehension of information presented in a written format; and (6) self-expression in various creative writing forms.

Coherence level verbal-linguistic developmental journey is reported by Wessman to involve “development of the creative and self-expressive dimensions of linguistic communications and expanded comprehension and interpretive capacities” including (1) the ability to create original stories and relate classically and previously heard stories; (2) execution of various types of formal speaking; (3) skilled use of various figures of speech; and (4) ability to engage in metalinguistic analysis and dialogue. (Wessman, nd, 1) Wallace (2007) writes that the greatest of all challenges English language learners must overcome to read at the grade level appropriate for their age is certainly “a lack of sufficient vocabulary development. The use of cognates, teaching the meaning of basic words and review and reinforcement are important steps in developing the vocabulary of English language learners. Direct instruction in vocabulary, combined with word-learning strategies, was also found to be effective. Ultimately, vocabulary knowledge is a critical component of reading comprehension.” (cited in Wessman, nd, 1).

Vocabulary depth of word knowledge is reported to include …all word characteristics such as phonemic, graphemic, morphemic, syntactic, semantic, collocational and phraseological properties” (Quian, 2002, p. 516 in Coyne, et al, 2009, 1) Breadth and depth are critically important in learning English vocabulary and this makes the question of what the best method is in the provision of instruction in English vocabulary or specifically what memory techniques for learning English vocabulary are the most appropriate and effective for English vocabulary learning. While breadth or the number of words known by the student or word meanings contained in the student lexicon is a “…primary dimension of vocabulary knowledge depth” and another is stated to be that of “significant dimension. Knowledge of each word meaning exists on a continuum from no knowledge to varying levels of partial knowledge to more complete and full knowledge.” (Coyne, et al, 2009, 1)

Coyne reports the depth of word knowledge to hold “important implications for listening or reading comprehension. How well, or deeply, a word is known determines whether or not it can be discriminated from other words and understood in novel contexts or in different morphosyntactic forms. Therefore, another critical goal of direct vocabulary instruction is to help students develop sufficient depth of word knowledge to support comprehension. Instructional approaches that focus on developing depth of vocabulary knowledge most often provide students with extended opportunities to discuss and interact with words outside story readings.” (Coyne, et al, 2009, 1)

Coyne et al report that benefits have been shown to be linked to extended vocabulary instruction.” (2009) Extended instruction is reported to “..allocate more instructional time per word” meaning that student “…receive more encounters with and exposure to target vocabulary. Extended vocabulary instruction also provides students with opportunities to interact with words outside the narrative constraints of the story. This allows teachers to give students examples of how target words can be used in multiple and novel contexts.” (Coyne, et al, 2009, 1) In addition, the focus of activities of extended instruction is on “enabling students to engage in rich dialogic interactions around words and word meaning. The deep and refined knowledge of word meanings that is the goal of extended instruction may better support comprehension across varied contexts.” (Coyne, et al, 2009) The primary limitation of extended vocabulary instruction is the amount of time required to teach each target word.” (Coyne, et al, 2009, 1).

Breadth, or the “number of words known” can be clearly differentiated from vocabulary depth. The work of Coyne et al (2009) reports a study that compared two methods for direct teaching of word meanings to kindergarten students. The participants in the study included a 42-kindergarten student who was taught nine target words and three with each method used in this study. Coyne et al state that students enter school “…with significant differences in vocabulary knowledge and these differences grow larger in the early grades. Converging evidence has suggested that instruction in code-based skills is insufficient to meet the needs of students who are at risk for experiencing reading problems because of language and vocabulary difficulties.” This highlights the growing acknowledgment of the critical nature of vocabulary development acceleration in students at a young age through use of “targeted and teacher-supported instruction and other intervention efforts.” (Coyne, 2009, 1)

Coyne et al (2009) additionally report that individuals interested in academic achievement being accelerated are presented with barriers in regards to the better way to “leverage scarce instructional time. In vocabulary intervention research, discussions about leveraging instructional time often revolve around the trade-offs between teaching for breadth or depth.” When kindergarten begins each year the students generally know literally thousands more meanings to words than peers who are considered “at risk of language and learning difficulties” with this gap growing even wider in the primary school grades. (Coyne, et al, 2009, paraphrased)

Biemiller and Slonim (2001) have stated estimations that children with large vocabularies by second grade “…know approximately 4,000 more root word meanings than children with delays in vocabulary development.” (Coyne, et al, 2009, 1) It is reported that the breadth of a learner’s word knowledge “is the number of words for which the individual has at least some familiarity with their meaning. “ (Curtis, nd, 1) The importance of the individual’s vocabulary breadth is important because the more word meanings learners know, the easier it is for them to acquire new ones.” (Curtis, nd, 1).

Having a big vocabulary is reported to be “a prerequisite for reading (and presumably) listening ability.” (Meara, 2010, 1) Vocabulary size also is stated to be, potentially, a reliable predictor “not just of reading success, but of overall linguistic competence.” (Meara, 2010, 1) In first language acquisition, “the processes of vocabulary development and grammar development are closely intertwined, with the former possibly driving the latter.” (Meara, 2010, 1) It is reported that only after children have vocabularies “of several hundred words [do] they begin to produce in earnest grammatical speech, which suggest to Tomasello ‘that learning words and learning grammatical constructions are both part of the same overall process.” (Meara, 2010, 1).

The work of Miller and Taylor reports that when vocabulary learning is considered by teachers for second language learners, “it is essential to determine whether students have adequate receptive and expressive vocabularies in their first, if they can read in their first language, and their developmental age and age of acquisition for the their second language, which can affect their ability to understand concepts. It is important to decide which expressive and receptive vocabularies to assess, the first language, or the target language; the student’s second language.” (nd, 1)

There are various factors known to affect the vocabulary learning of students therefore, teachers “…have to know as much as possible about the individual students. It is important to keep careful records of speech interactions and seek to understand the student’s history with regards to language learning.” (Miller and Taylor, nd, 1) A student’s vocabulary is reported to be greatly influenced “…by the amount of talk in their environment, bilingual students’ vocabulary is influenced by the amount of talk in each language. Therefore, bilingual students may have a restricted vocabulary in each language. Their teachers need to understand this as they interpret assessments, and they should work to expand their students’ vocabulary (Tabors & Snow, 2004 cited in Meara, nd, 1). It might behoove teachers to assess oral language proficiency in both languages to better understand their students’ strengths and weaknesses in this area.” (Miller and Taylor, nd) Tabors and Snow (2004) have reported concern that learning to read in a language that the individual has not yet mastered “carries with it the risk that students will not understand that reading is about making meaning.”(cited in Meara, nd, 1)

The work of Yamashita and Jiang (2010) investigated first language and its influence on the acquisition of second language collocations using a framework based on Knoll and Stewart (1994) and Jiang (2000) through a comparison on the performance on a phrase-acceptability judgment task among native speakers of English, Japanese English as a second language (ESL) users and Japanese English as a foreign language (EFL) learners. The test materials are reported to have included

“both congruent collocations, whose lexical components were similar in L1 and L2, and incongruent collocations, whose lexical components differed in the two languages. Findings in the study show that EFL learners made more errors and reacted more slowly to incongruent collocations than congruent collocations. ESL users were found to perform generally better than EFL learners (low error rate and faster speed) but they still made more errors on incongruent collocations than on congruent collocations. The results suggested that: (a) both L1 congruency and L2 exposure affected the acquisition of L2 collocations with the availability of both maximizing this acquisition, and (b) it is difficult to acquire incongruent collocations even with a considerable amount of exposure to L2; and (c) once stored in memory, L2 collocations are processed independently of L1.” (Yamashita and Jiang, nd, 1)

Vocabulary breadth and depth are distinguished as vocabulary depth of word knowledge is reported to include …all word characteristics such as phonemic, graphemic, morphemic, syntactic, semantic, collocational and phraseological properties…” while vocabulary breadth is the number of words the individual knows. The number of words known by an individual directly affects their ability to read and listen. The more the individual hears the words spoken and uses them in speaking the more proficient the individual becomes at reading. This means that the native speaker and the English as Second Language learner are more familiar with the words making them more proficient at reading than the English as a foreign language learner who rarely if ever hears the English words they are learning spoken aloud.

Children Learning Their First Language

According to Miller and Taylor (nd) vocabulary is “not decoding or word identification; rather, the focus is always on meaning. When students learn to read they use their oral vocabulary to begin to develop and text or reading vocabulary. Vocabulary knowledge is tied to comprehension.” (Miller and Taylor, nd, 1) The work of Lefever (2007) states that Young learners have the following characteristics: (1) they are keen and enthusiastic; (2) they are curious and inquisitive; (3) they are outspoken; (4) they are creative and imaginative; (5) they are active and like to move around; (6) they are interested in exploration; (6) they learn by doing; (7) they are holistic, natural learners searching for meaningful messages. (Lefever, 2007, 1)

According to Pinter (2005) “There are some advantages that young learners have over older ones. Young children are sensitive to the sounds and the rhythm of new languages and they enjoy copying new sounds and patterns of intonation. In addition, younger learners are usually less anxious and less inhibited than older learners.” (Lefever, 2007, 1)

Lefever additionally states that the needs and characteristics of young learners “have implications for language instruction. Teachers should provide a wide range of opportunities for hearing and using the language and play should be an active part of the teaching. Tasks should be meaningful and help children to make sense of new experiences by relating them to what they already know. The use of routine and repetition should be emphasized along with opportunities for interaction and cooperation.” (2007, 1) Lefever reports that maintaining the positive attitudes, motivation and self-confidence of children requires both praise and encouragement.

Piaget held that the development of logical thought is dependent on social interaction. Piaget wrote “…complete reversibility presupposes symbolism, because it is only by reference to the possible evocation of absent objects that the assimilation of things to action schemes and the accommodation of action schemes to things reach permanent equilibrium, and thus constitute a reversible mechanism. The symbolism of individual images fluctuates far too much to lead to this result. Language is, therefore, necessary and thus we come back to social factors.” (1945/1995a, p.154)

Piaget linked the role of social interaction to the importance of language. Piaget held that language played a role in the development of conceptual and logical understandings. The work of Becker and Varelas states that this theory “…provides an account of two developments of the semiotic function. The first is a development from the absence of representation to the generation of mental images that arise from perception and action, which Piaget considered to be strongly tied to experiential knowing. The second is a development from such mental images to arbitrary conventional signs, which Piaget considered to be less directly tied to experiential knowing. In this theory, the signifier is at first an internal image derived from perceptions and actions and resulting from extended accommodation. At this point, though is still particular and individual. The development from the first signifiers to signifiers that support the development of logical thought arises from the “intervention of language.” (Becker and Varelas, 1997) Piaget wrote the following to illustrate this view:

” We have to attempt to determine the connection between the imitative image, ludic symbolism and representative intelligence, i.e., between cognitive representation and the representation of imitation and play. This very complex problem is still further complicated by the intervention of language, collective verbal signs coming to interfere with the symbols we have already analyzed, in order to make possible the construction of concepts. It is moreover unnecessary to emphasize that this irreversible centration of the first conceptual representations is mainly expressed socially as egocentrism of thought…” (1945/1995a cited in Becker and Varelas, 1997, 1)

In other words, since a “concept centered on typical elements corresponding to the lived experience of the individual and symbolized by an image rather than by language, could neither be a general notion nor be capable of being fully communicated.” (Becker and Varelas, 1997, 1) The idea of Piaget in the foregoing passage is stated to be that “the arbitrary nature of the signifiers of a language facilitates a relative detachment of the concept from the lived experience to which it refers and that this relative detachment is necessary for the concept to become an instrument of logical reasoning.” (Becker and Varelas, 1997, 1) It is reported that Piaget viewed language, as “inherently a social factor partly because of the conventional nature of words and it is just this conventional nature of words that Piaget saw as crucial for conceptual development.” (Becker and Varelas, 1997, 1)

The work of LeGard (2004) states that Vygotsky perceived the child “…as a social being who is able to appropriate new patterns of thinking when learning alongside a more competent individual. He called this concept, the Zone of Proximal Development. This is the expanse between the child’s level of development and their potential development level, in collaboration with more competent individuals.” According to LeGard social interaction “…supports the child’s cognitive development in the ZPD, leading to a higher level of reasoning.” (2004, 1)

According to Vygotsky, there are two functionalities of language: (1) inner speech used for mental reasoning; and (2) external speech used to converse with others. (LeGard, 2004, 1) These operations are reported by LeGard (2004) “to occur separately.” Before the child is two years of age the words are used by the child socially but have no internal language meaning. However, upon thought and language merging “the social language is internalized and assists the child with their reasoning.” (LeGard, 2004, 1) Therefore, LeGard states that the social environment is “ingrained within the child’s learning.” (2004, 1)

Constructivist theory holds that learning is exploratory in nature and that the individual learner and the learner’s comprehension occurs relative to stages of cognitive development. LeGard (2004) writes that social constructivism “…maintains that knowledge is constructed by an understanding of social and cultural encounters and by the collaborative nature of learning. Social constructivist theory emphasizes the significance of adult tuition with the teacher occupying an active role.” (2004, 1).

The work of Richers (nd) entitled “How Did They Do It? Language Learning in Bruner and Wittgenstein” states that it was suggested by Bruner that children “…typically need not be drilled as suggested, but that they have a natural tendency towards both mutual attention and agreeing on reference (“referential intersubjectivity”, Bruner 1983, 27, 122), which is augmented by a device to acquire language.” To Bruner, the infant has a “natural disposition systematicity and means-end abstraction, which is augmented by the constrained, familiar situations of action and interaction, which support a high degree of order. Infants are extraordinarily social and communicative…” (Bruner, 1983 cited in Richers, nd, 1) Richers writes that children provide an eager response to the actions of others and spend a great many hours playing and

“…doing a limited number of things with their caretakers, repeatedly going through the child’s ever-growing repertoire of games, responding to prompts, exchanging smiles, and so forth. Underlying a child’s approach to the world is a nave realism: children do not question the existence of mental phenomena, other beings or physical objects. At first, they cannot distinguish between thoughts and things, or between others’ and their own mental activity. But even extremely young children have communicative intentions that they try to make clear through constant and repeated negotiations. Over time, such negotiations lead to ever more complex communication and then to recognizable linguistic procedures, to language games. Language learning consists not only of learning grammar but “of realizing one’s intentions in the appropriate use of that grammar” (Bruner 1983, 38 cited in Richers, nd, 1).

Bruner posited a Language Acquisition Device (LAD) to explain children’s language learning.

The work of Pinter (2006) entitled “Teaching Young Language Learners” notes various reasons why children benefit from foreign language learning. Those benefits include such as

- development of the basic communication skills of the child;

- encouragement and motivation gained for language learning;

- promotion of learning about other cultures;

- development of the cognitive skills of the child;

- development of the metalinguistic awareness of the child;

- encouragement for learning to learn. (cited in Lefever, 2007, 1)

Lefever writes that foreign language instruction for young learners is quite challenging for educators. One reason is that English is learned by children at various ages and therefore children have levels of English proficiency that are different. This means teachers have to be prepared to cope with the mixed levels of language skills of children as well as mixed levels of knowledge. Also stated, a challenge is that children often are not proficient at reading and writing in their native language prior to beginning to learn an additional language. Also stated as a challenge is educating teachers with enough English skills and knowledge of methodology in teaching language to young learners. Lefever states that language programs should be both “flexible and conducive to effective learning.” (2007, 1).

The work of Erika Hoff and Jodi McKay entitled “Phonological Memory Skill in Monolingual and Bilingual 23-Month-Olds” reports that word learning includes the formation of a lexical entry or stated otherwise when the child encounters a new word that word must be stored in the child’s memory as a new sound sequence. (Paraphrased) According to Hoff and McKay memory is dependent on possessing a “system of representation that captures the to-be-remembered stimuli.” (2004, 1) Children who are learning two languages are reported to potentially have systems of phonological representation for each language that is not established as well as their monolingual peers. In fact, evidence from a study of two-year-old children indicates that bilingual children “…may process both their languages through a single phonological system—the system of whichever language the child hears more.” (Navarro, 1998; Navarro, Pearson, Cobo-Lewis, & Oller, 1998 in Hoff and McKay, 2004, 1)

The evidence is stated to demonstrate that: (1) phonological memory is related to vocabulary learning; (2) phonological memory is related to knowledge of the phonological system to which new sound sequences conform, and (3) bilingualism affect phonological development suggest that bilingual children have phonological memory skills that are less developed than their monolingual peers. (Hoff and McKay, 2004) In fact, sound evidence exists to indicate that bilingual children and young adults “have smaller vocabularies in each of their languages than do monolingual children of the same age.” (Hoff and McKay, 2004, 1) It is currently held that this difference is related to the amount of input received by the children in each language. The evidence in this area of the study indicates that bilingual children are more challenged in learning new words due to a difficulty experienced in new sound sequence memory.

Reports state that children who grow up with two or more languages are many times “slower to talk than a monolingual child.” It is reported that this is not surprising “given the amount of analysis and code-cracking necessary to organize two systems simultaneously, but the lifelong advantage of knowing two native languages is considered an appropriate balance to the cost of the potential delay.” (Lewin, 2011, 1) Bilingualism is reported to be the norm throughout the modern world with monolinguals being the exception to the rule. It is reported that learning of each language for the bilingual child “proceeds…much the same way as it does [for] the monolingual child…” although “some mixing may be observed, in which the child uses words or inflections from the two languages in one utterance.” (Lewin, 2011, 1)

In a York University report entitled “Bilingualism, Biliteracy, and Learning to Read; Interactions among Languages and Writing Systems” it is reported that bilingual students have the advantage of “a general understanding of reading and its basis in a symbolic system of print.” (Early Advantage, 2011, 1) It is reported that it is possible to acquire this general understanding “in any writing system” which provides children “an essential basis for learning how the system works and how the forms can be decoded into meaningful language.” (Early Advantage, 2011, 1) Bilingual children are accustomed to thinking of more than word work in relation to an object and because of this, they are reported to be “more sensitive to language as a system made up of distinct sounds. This sensitivity can be transferred to reading as the child learns to associate the letters in print with sounds.” (Early Advantage, 2011, 1) It is reported that what it is all about in reality is the child’s “decoding ability” in which the children are able to grasp more quickly the “concept that letters make sounds.” (Early Advantage, 2011, 1) The same concept is reported to be one that can be “applied to both languages, and suddenly a light goes on. It’s a transferable set of strategies and expertise.” (Early Advantage, 2011, 1) This general sensitivity to language is reported to be often referred to as “metalinguistic awareness” which results from ‘exposure over time to more than one language – regardless of the language.” (Early Advantage, 2011, 1)

A second benefit realized by Bilingual children is reported as the “potential for transfer of reading principles across the languages, or the likely possibility that the children will take the methods and insights they’ve built up in one language and apply them to advance more rapidly in the other language.” (Early Advantage, 2011, 1) The York University study found that bilingual children “we’re all learning to read in both languages at the same time…” (Early Advantage, 2011, 1) The study results demonstrated that the advantage of bilingual kids “was independent of instruction time in the other language. The key was not so much how many hours were spent practicing as the ability the other language gave them to combine their insights and strategies. The York University team credited this as “the additional advantage of applying the concepts of reading that they learn to their two languages, enhancing both and boosting their passage into literacy.” (Early Advantage, 2011, 1)

Research Study

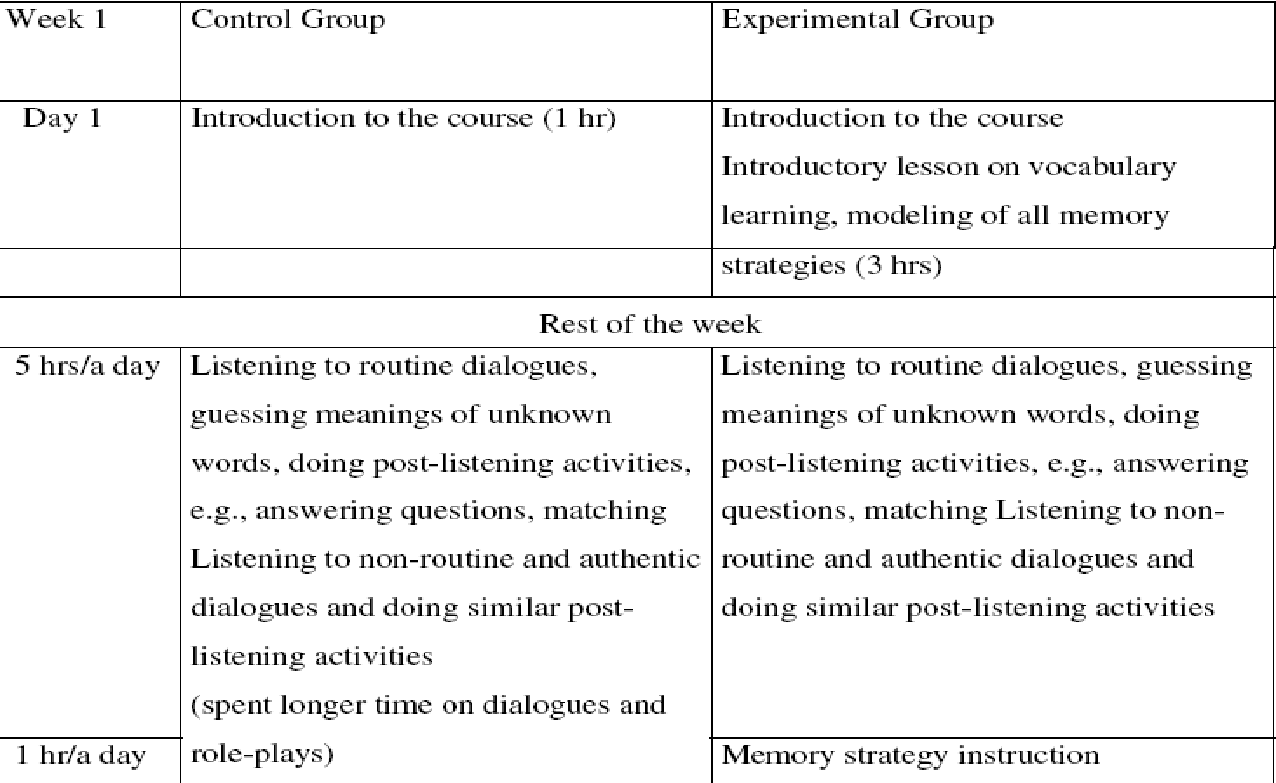

The research in this study sought to determine whether students who were trained in memory strategies would be more successful at English vocabulary learning than students who did not receive memory strategy training. The study involved students in the experimental group receiving training one hour per day in memory strategies for learning English vocabulary words and in a technique otherwise known as Mnemonics. The control group did not receive this training intervention.

The control in this study received no instructions regarding memory or mnemonic learning strategies while the experimental group did receive one hour of instruction each day on this memory strategy. The design of this study is illustrated in the following figure labeled Figure 1 in this study.

The study included three specific memory strategy learning exercises:

- Exercise 1 – Acronym memory strategy;

- Exercise 2 – Rote Repetition Memory Strategy; and

- Exercise 3 – Use of Imagery Memory Strategy

Each of these memory strategies for learning is described in the following section.

Memory Exercises

Exercise 1: Acronym – Invented Combination of Letters with Each Letter Cue to Word

The first memory exercise in this study involved students learning ‘key’ vocabulary words through the use of a technique referred to as Mnemonics and specifically through the use of an Acronym or an invented combination of letters with each letter acting as a cue to word that the students needed to remember. The words the students needed to remember in this exercise were those as follows:

- Straight

- Under

- Nocturnal

- Ladle

- Insignia

- Ground

- Height

- Trouble

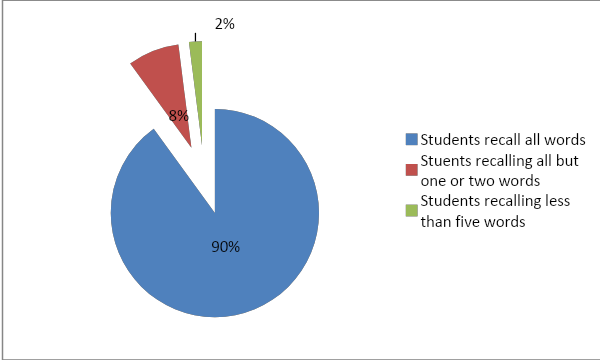

The first letter of each word was taken to form the word ‘S-U-N-L-I-G_H-T and this Acronym was utilized for tickling the memory of the students so that might better remember each of these vocabulary words and the correct spelling for these words. This technique was found to be successful in assisting students with remembering vocabulary words as shown in the following percentages of results from the Experimental Group in this study:

- Students recalling all vocabulary words in this exercise – 90%

- of Students recalled all but one or two words I this exercise – 8%

- Students recalling less than five words in this exercise – 2%

The Control Group results in Exercise 1 are as follows:

- Students recall all words – 22%

- Students Recall All but One or Two Words – 72%

- Students recalling less than five words – 1%

Exercise 2: Rote repetition

The second exercise in this study involved students learning 20 words. The 20 words were presented in 10 groups of two words that are opposite from one another. The words in this exercise were the following words:

These word combinations of opposites were reviewed twice per day for five consecutive days and the word combination lists were sent home with students over the weekend for study. The word lists were accompanied by illustrations of the meanings of the opposite words. The word lists were then reviewed again twice per day in the classroom for two consecutive days and on the third-day students were tested on their recall of these opposite word combinations. As shown in the following chart this technique was very successful in assisting students with vocabulary memory and recall.

Experimental Group Results: Correct Student Recall of Words in Exercise 2:

- About/ exactly 82%

- Above/below

- 100%

- Absence/presence 100%

- Abundance/lack 88%

- to accept/to refuse 100%

- accidental/intentional 100%

- active/lazy 92%

- to add/to subtract 100%

- to admit/to deny 100%

- adult/child 100%

Average for all word combinations in memory recall – 96.2%

Control Group Results Correct Student Recall of Words in Exercise 2:

- About/ exactly 66%

- Above/below 80%

- Absence/presence 75%

- Abundance/lack 77%

- to accept/to refuse 88%

- accidental/intentional 65%

- active/lazy 89%

- to add/to subtract 80%

- to admit/to deny 81%

- adult/child 82%

Average Correct Recall of Vocabulary Words – 77.3%

Exercise 3: Use of Imagery

The third exercise in this study involved the use of illustrations of common objects in the environment in assisting the students with learning English vocabulary words. The words that students were required to learn in this exercise include those as follows:

- Library

- Police Department

- Hospital

- Clinic

- Church

- Gymnasium

- Fire Department

- Ambulance

Each of these words was printed in English beside an illustration of the object along with the word in the student’s native language being printed on the opposite side of the illustration for the purpose of allowing the student to reference the word. The students had ample time to study this handout as it was part of classroom instruction for a period of five days followed by students taking the handout home over the weekend with homework instructions to study the handout and gain confidence in learning the vocabulary words in English. The students returned to school on Monday and a review of this handout was conducted on both Monday and Tuesday prior to the exercise in this study being administered.

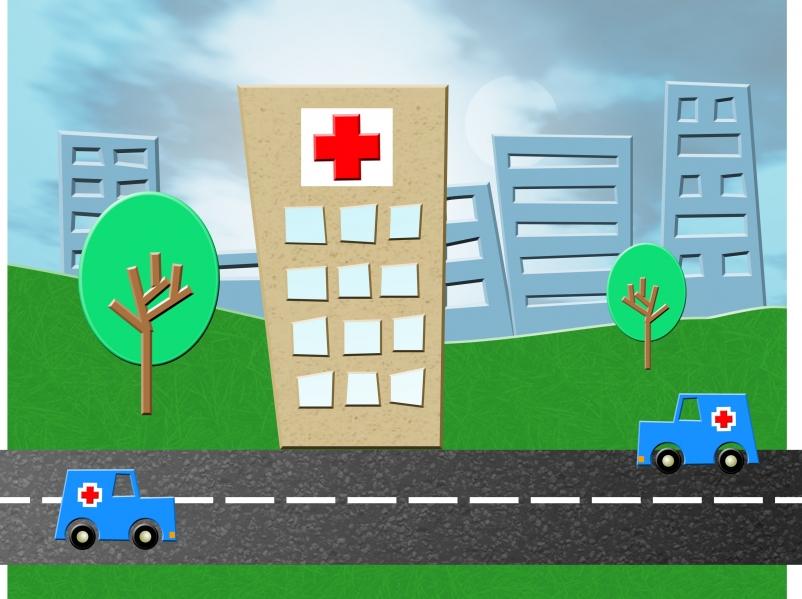

The illustrations used in this study for assisting students correctly with a recall of vocabulary words are shown in each problem in this Exercise and the results are listed following each illustration.

(The word library in student’s native language).

Experimental Group Results:

- There was a 95% recall of the word library among students in this exercise.

- Correct spelling of the word was accomplished by 72% of the students.

Control Group Results:

- There was a 75% recall of the word library among students in this exercise.

- Correct spelling of the word was accomplished by 55% of the students.

Experimental Group Results:

- Students correctly recalling vocabulary words ‘Police Station’ – 89%

- Students correctly spelling vocabulary words ‘Police Station – 71%

Control Group Results:

- Students correctly recalling vocabulary words ‘Police Station’ – 75%

- Students correctly spelling vocabulary words ‘Police Station – 59%

Experimental Group Results:

- Students correctly recalling vocabulary word ‘hospital’ – 92%

- Students correctly spelling vocabulary word ‘hospital – 90%

Control Group Results:

- Students correctly recalling vocabulary word ‘hospital’ – 79%

- Students correctly spelling vocabulary word ‘hospital – 68%

Experimental Group Results:

- Student correctly spelling vocabulary word ‘church’ – 97%

- Students correctly spelling vocabulary word ‘church’ – 94%

Control Group Results:

- Student correctly spelling vocabulary word ‘church’ – 81%

- Students correctly spelling vocabulary word ‘church’ – 79%

Experimental Group Results:

- Students correctly recalling vocabulary word ‘Gymnasium’ – 82%

- Student correctly spelling vocabulary word ‘Gymnasium – 77%

Control Group Results:

- Students correctly recalling vocabulary word ‘Gymnasium’ – 65%

- Student correctly spelling vocabulary word ‘Gymnasium – 52%

Experimental Group Results:

- Students correctly recalling vocabulary word ‘Fire Station’– 95%

- Student correctly spelling vocabulary word ‘Fire Station’ – 81%

Control Group Results:

- Students correctly recalling vocabulary word ‘Fire Station’– 79%

- Student correctly spelling vocabulary word ‘Fire Station’ – 62%

Experimental Group Results:

- Students correctly recalling vocabulary word ‘ambulance’ – 82%

- Student correctly spelling vocabulary word ‘Gymnasium – 67%

Control Group Results:

- Students correctly recalling vocabulary word ‘ambulance’ – 71%

- Student correctly spelling vocabulary word ‘Gymnasium – 55%

Experimental Group Average Results

- Average correct responses on vocabulary words in Exercise 3 or in other words students correctly recalling vocabulary words averaged 90.3%.

- Average correct Responses on the spelling of vocabulary words in Exercise 3 or in other words students who correctly recalled and then correctly spelled the vocabulary words in Exercise 3 averaged 79.4%.

Control Group Average Results in

- Average correct responses on vocabulary words in Exercise 3 or in other words students correctly recalling vocabulary words averaged 75%.

- Average correct responses on the spelling of vocabulary words in Exercise 3 or in other words students who correctly recalled and then correctly spelled the vocabulary words in Exercise 3 averaged 61.4%.

These findings affirm the findings in the study reported by Atay and Ozbulgan (2007) entitled “Memory Strategy Instruction, Contextual Learning and ESP vocabulary recall” in which it is reported that memory strategies (traditionally known as mnemonics) have been found to enhance remembering through the connecting of new knowledge with familiar words and images.” (p.40) Thompson (1987) states Mnemonics that this strategy is effective and works “…by utilizing some well-known principles of psychology: a retrieval plan is developed during encoding, and mental imagery, both visual and verbal, is used. They help individuals learn faster and recall better because they aid the integration of new material into existing cognitive units and because they provide retrieval cues (p. 211)

Discussion

The present study had as its’ aim to examine the effects of memory strategy instruction in combination with learning through context on the vocabulary knowledge of learners of English vocabulary and compare it with those with no instruction on memory strategy for English vocabulary learning. As cited in the work of Macaro (2001) “just making learners aware of the existence of strategies and exploring the range of available strategies’ was not enough to bring about effective use of the strategies. However, students in the present study were shown specifically the strategies that could be used by them in achieving better learning. The students discussed these strategies and practiced these strategies and were provided feedback by the teacher. While the students in the control group remained seated during the present study, the students in the experimental group were not only allowed but were required to move around the classroom and collaborate among themselves regularly. This process assisted them in learning the type of memory strategies that were used by other students and enabled them to apply these strategies to their own learning of English vocabulary.

Summary

The findings in this study demonstrate that the use of memory learning strategies for achieving better vocabulary learning was effective for the students in the experimental group. As noted in Exercise 1 – Acronym Use for Vocabulary Learning. The students in the experimental group that recalled all vocabulary words in the list are reported at 90% as compared to the control group percentage of 22% of students recalling all words in this exercise.

Exercise 2 in the experimental group states results of an average of 96.2% providing correct vocabulary word recall as compared to the control group average of 77.3% correct responses in vocabulary word recall.

The Experimental group’s correct responses to vocabulary words in Exercise 3 are stated at an average of 90.3% while the control group’s correct responses average in Exercise 3 is stated at 75%, a clear indicator of the effectiveness of the memory learning strategies for vocabulary learning in the experimental group. The experimental group’s average correct responses on the spelling of vocabulary words are stated at 79.4% as compared to the average of 61.4% for the control group, again a clear indicator of the effectiveness of the memory strategies for vocabulary learning in the experimental group in this study.

Findings in this study affirm the findings in other previous studies on memory strategies for English vocabulary learning through the use of Mnemonics or memory learning strategies. Atay and Ozbulgan (2007) report that the development of lexical knowledge “occupies an important position in the learners’ struggle to master a second foreign language.” (p.40) Researchers state that vocabulary-learning strategies “facilitate the acquisition of a new lexis in the second/foreign language as they aid in discovering the meaning of a new word and in consolidating a word once it has been encountered.” ( p. 40) Successful vocabulary learners are those who are active users of strategy and who are “conscious of their learning” and who take steps to regulate that learning. In comparison, poor learners “display little awareness of how to learn new words or how to connect new words to old knowledge.” (Atay and Ozbulgan, 2007, p.40)

References

Atay, Derin and Ozbulgan, Cengiz. Memory Strategy Instruction, Contextual Learning and ESP Vocabulary Recall. English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 39-51.

Becker, Joe and Varelas, Maria. Piaget’s Early Theory of the Role of Language in Intellectual Development; A Comment on DeVrie’s Account of Piaget’s Social Theory. Educational Researcher, 1997. Vol. 30, No.6. Web.

Bruner, Jerome. Child’s Talk: Learning to Use Language. 1983. New York: W. W. Norton & Company.

Coyne, Michael D., et al. Direct Vocabulary Instruction in Kindergarten: Teaching for Breadth versus Depth. The Elementary School Journal. 2009. Volume 110, No. 1. 2009. University of Chicago. Web.

Curtis, Mary E. The Role of Vocabulary Instruction in Adult Basic Education. Date Unknown. Vocabulary Instruction in ABE. Web.

Does Bilingualism Help Children Learn to Read? Early Advantage. 2001. Web.

Hoff, E. and McKay, J. Phonological Memory Skill in Monolingual and Bilingual 23-Month-Olds. 2003. Proceedings of the 4th International Symposium on Bilingualism, ed. James Cohen, Kara T. McAlister, Kellie Rolstad, and Jeff MacSwan, 1041-1044. Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press. Web.

Lefever, S. English for Very Young Learners. The Association of Teachers of English in Iceland. FEKI. Aberdeen Skotlandi 18-22 2007. Web.

LeGard, W.T. Piaget Versus Vygotsky. Scribd. 2007. Web.

Lewin, Kurt. Language Delay – Monolingual vs. bilingual, Language delay and hearing loss, Language delay and mental retardation. 2001.

Macaro, E. Learning strategies in second and foreign language classrooms. London: Continuum in: Atay, Derin and Ozbulgan, Cengiz. Memory Strategy Instruction, Contextual Learning and ESP Vocabulary Recall. English for Specific Purposes 26 (2007) 39-51.

Meara, Paul. V is for Vocabulary Size. 2010. An A-Z of ELT. Web.

Miller, S.A. and Taylor, D.L. Vocabulary development for at-risk middle school students and English language learners. Date Unknown. Vocabulary Development. Web.

Navarro, A.M. Phonetic effects of the ambient language in early speech: Comparisons of monolingual- and bilingual-learning children. 1998. Unpublished dissertation, University of Miami, Interdepartmental, Coral Gables, FL.

Navarro, A.M., Pearson, B.Z., Cobo-Lewis, A., & Oller, D.K. Identifying the language spoken by 26-month-old monolingual- and bilingual-learning babies in a no-context situation. 1998. In A. Greenhill, M. Hughes, H. Littlefield, & H. Walsh (Eds), Proceedings of the 22nd Annual Boston University Conference on Language Development (pp. 557-568). Somerville, MA: Cascadilla Press.

Piaget, J. Play, dreams and imitation in childhood. 1962(a) New York: Norton. (Original work published 1945)

Piaget, J. Supplement to L. Vygotsky, Thought and language. 1962(b) Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Piaget, J. The child and reality: Problems of genetic psychology.1973. New York: Viking. (Original work published 1972)

Piaget, J. Logical operations and social life.1995(a) In L. Smith (Ed.). Sociological Studies (pp. 134–157). London: Routledge. (Original work published 1945)

Piaget, J. Explanation in sociology. 1995(b) In L. Smith (Ed.). Sociological Studies (pp. 30–96). London: Routledge. (Original work published 1950)

Pinter, A. Teaching Young Language Learners. 2006. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Richers, N. (nd) How Did They Do It? Language Learning in Bruner and Wittgenstein. Philosophy of Language. Web.

Wessman, Leslie. Verbal-Linguistic Ways of Knowing.Date Unknown. Web.

Word.Merriam Webster Dictionary. 2011. Web.

Yamashita, J. And Jiang, N. L1 Influence on the Acquisition of L2 Collocations: Japanese ESL Users and EFL Learners Acquiring English Collocations. 2010. TESOL Quarterly, Vol. 44, No. Web.