Introduction

The feminist movement is spread all over the world, and more and more people are sharing their values. In the context of the modern era, the position of women has changed. Discrimination based on gender is slowly vanishing from our reality, though it is still an issue in emerging countries. The patriarchal type of relations has almost disappeared, and household duties are usually shared by family members. Such positive changes would be impossible without the influence of passionate women, who stand for their rights. Although the feminist movement is still making a huge impact on global society, some of its aspects have changed throughout time, and this paper is focused on observing the present-day agenda in comparison with previous goals and achievements of feminism.

Liberal Feminism

The definition of liberal feminism is the following: “a particular approach to achieving equality between men and women that emphasizes the power of an individual person to alter discriminatory practices against women” (“Liberal Feminism: Definition & Theory” par. 2). In other words, it is based on the idea that in a democratic system women can create an equal society where law and men respect them. It should be noted that democratic institutions have developed significantly, so nowadays women have more opportunities for action. However, every movement has different directions, and liberal feminism can be addressed from two points of view: middle-class and working-class feminism.

Middle-class Feminism

The division by class here is for a reason. A famous activist bell hook claims that in the US middle-class white women had more opportunities to fight for their interests than women from other class and race (hooks 6). It means that privileged women had access to media, universities, and other public institutions, unlike others, so they could easier address the large audience.

The problems that middle-class feminists were highlighting mostly concerned about their isolation and inequality in the labor market. “The Feminine Mystique” by Betty Friedan, which illustrated the sad truth about the life goals of women, provoked a massive reaction and protest. Friedan disagreed with the nationwide promotion of early marriages and family as the only goal for women and revealed the problem of never questioning. It was torturing women, who did not even realize their true state of mind (Friedan 54). Hence, the movement became focused on highlighting women’s individuality and abilities to make an impact in society along with men.

Working-class Feminism

The status of working-class women was always vulnerable and open to debate. Firstly, as workers, they had to face the dehumanizing nature of labor and suffered from poverty daily. Furthermore, they were suspicious about middle-class women’s attempts to get a place at the labor market and knew that this liberation movement threatened their jobs (hooks 98). Therefore, the main struggle for them was to get decently paid and to avoid total discrimination.

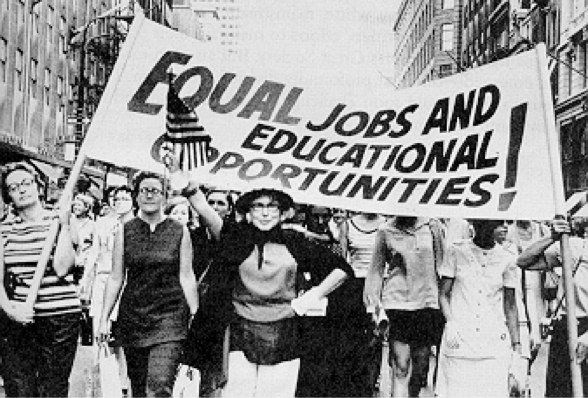

All in all, liberal feminism was reflected in massive protests and public speeches, which finally reached many of its primary goals. In 1920 American women finally obtained the right to vote. Later, it became possible for women to work in the same positions as men. Today’s feminism missions would be much more complicated without this progress. Gender discrimination at work is gradually vanishing, and women keep raising awareness about it in order to eliminate it completely. Erasing these inequalities contributes to making a healthy society, where people respect each other and value work of the others.

Radical Feminism

Another school of feminism is called radical and focuses on fighting against male violence and patriarchy. Challenging the patriarchy means dealing with male dominance at home and at work (Mackay 4). Unfortunately, men’s supremacy has been a feature of every community for a long time. Hence, the concepts of radical feminism are interconnected with ideas of the liberal school, as male supremacy was always one of the major concerns for all women.

Radicals stress the topic of rape and violence. This is a critical issue that has always been hard to discuss. Women had never been eager to share their traumatic experiences and to combat violence at home until some brave activists began the public protest. It caused a tidal wave of disagreement, and it is noteworthy that women living in civilized countries can feel safe nowadays. Law protects them and brings confidence to millions of women across the world.

However, there are still many countries where the state does not protect from violence. It happens because of the reluctance of members of these societies to make a change. Possibly, they underestimate the features of healthy societies, and it results in indifference.

Agency

Modern feminism would not have been what it is without influencers and activists from the past. Literature, music, and other cultural ways of transferring a message helped feminists to widespread their ideas and beliefs. Second-wave feminism was the period when the movement was at its peak, so most of the remarkable works concerning the position of women in society were created at this time. Along with authors who discussed basic women’s rights, like bell hooks, others promoted the topics which had never been talked about before. For example, Erica Jong developed a theme of female sexuality in her novel “Fear of Flying” published in 1973. It was a provocative subject for those days, but it was time for the society to reconsider conservative views and accept the natural causes of the phenomenon.

Another outstanding example in modern feminism is Alice Walker, a writer who coined the term “womanism.” It was meant to symbolize all women, including the black ones, as “feminism” did not usually encompass them. According to Walker, “womanism” is a philosophy of women who love their gender, which also addresses all issues mentioned above (Junior 16). Although the opposite term “misogyny” has been popular lately, there are still many proponents of Walker’s views.

In the context of education, the feminist movement became a global appeal for critical thinking and overviewing the common concepts of the position of women. Women started asking themselves, and they finally realized that their opinion and self-respect matter. It is important that the ideas of feminism gave a sense of community to women, and this sense of participation brought power and confidence to many of them. Women became capable of debating openly over controversial topics. This is how the slogan “the personal is political” occurred – it addressed the connection between the self and political reality. It was one of the first steps in discussing the subject of political consciousness among women, and it seems especially important today when we finally see women-politicians, women-presidents.

To sum up, the contemporary feminist movement has progressed to the state of a global and powerful philosophy which helps women worldwide. Fashion claims that the future is feminine, men join the movement and support active women, and this would never be true without the founders and previous activists, who were first to declare women’s rights. Besides, today’s agenda has become more diversified, and feminists’ concerns are not only about women but also about global development in general. Thus, the efforts of the first feminists were not useless, and future generations can rely on modern activists.

Works Cited

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. W.W. Norton and Co, 1963

Hooks, bell. Feminist Theory: From Margin to Center. Routledge, 2014.

Jong, Erica. Fear of Flying. Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1973.

Junior, Nyasha. An Introduction to Womanist Biblical Interpretation. Presbyterian Publishing Corp, 2015.

Mackay, Finn. Radical Feminism: Feminist Activism in Movement. Springer, 2015.