Introduction

The open and fearless criticism of the political affairs of the particular state is always a risk for the author. No political authorities prefer being dishonored by any kind of article, news, or other types of critical expression. The modern world is a world of democratic countries that proclaim the freedom of thought and press. However, the practice shows that such notions as freedom and the right to express one’s thoughts are often no more than illusions. Whenever a particular person crosses the line of allowed criticism, some measures may be taken.

Many countries of the Middle East have become independent and announced the establishment of democracy in the previous century. Palestine is one of such countries. However, the democracy is this state is more about a mere concept than a reality. This idea was central to the art of the renowned Palestinian cartoonist Naji Al-Ali. In the following paper, the importance and influence of Naji Al-Ali’s personality and art will be examined and analyzed.

Biography

Early Life

Naji Al-Ali was a prominent Palestinian cartoonist famous for his criticism of the political situation in the country. Naji Al-Ali was born in 1936 or 1937 in Al-Shajara village in the Galilee. His native village was located near Nazareth. The childhood of Al-Ali was not happy because of the tragic historical events of those times. In 1948, Ali’s family was expelled from the new State of Israel that was created during the Arab-Israeli conflict. After leaving his native village, the boy grew up in the refugee camp of Ayn Al-Hilwa.

The historical situation in the region influenced the development of Ali’s talent and character significantly. Thus, it is necessary to have an insight into the historical context. The events of 1948 are referred to as the Palestinian catastrophe or the Nakba. Before the war, almost one million Palestinian Arabs lived on the newly established territory of the State of Israel. The mass expulsion of Arab people was the largest adverse impact. When the war was close to its end, in 1949, more than seven hundred thousand people left the country and became refugees.

Only one hundred and fifty thousand people stayed in Israel. It is relevant to mention predominant reasons for becoming refugees. Thus, most people were afraid of the Israeli attacks and preferred leaving their homes to find a safer place for living. When the Israeli forces became dominant in the region, they started practicing forced expulsion of people from their settlements.

The importance of Nakba for Palestinians cannot be overestimated. Michael Balfour dwells on the role and influence of those days by citing Edward Said: “For Palestinians, 1948 is remembered as the year of the Nakba, or catastrophe when 750 000 of us who were living there — two-thirds of the population — were driven out, our properly taken, hundreds of villages destroyed, and entire society obliterated.” Naji Al-Ali experienced all terrors and challenges of those times, and they became a basis for his future creativity.

Career

The cartoonist career of Naji Al-Ali began in that refugee camp in Lebanon. In the 1950s, Ali was already concerned about the political situation in the country. He was politically active and was not afraid to express his opinion openly. As a result, he was often detained and held in prison cells. They became his first canvases for creativity. Drawing became his passion and primary aim in life. He used drawing for the expression of his indignation concerning the severe constraints of the Palestinian people in refugee camps. As it is written in the newspaper Palestine News & Information Agency, “having realized such constraints, he swore then to immerse himself in politics and serve the Palestinian revolution by all the means at his disposal.”

Al-Ali received an education and mastered the mechanic profession at Tripoli. Although he had this education, he was still eager to proceed to withdraw. Thus, he decided to take a course at Lebanese Art Academy. He studied for one year. What concerned his personal life, Al-Ali was married and had four children. His wife was a woman from Safuriya village — Widad Saleh Naser.

Ghassan Kanafani was the person who inspired Al-Ali to continue his creative activity. He was the Palestinian writer who visited refugee camps. During one of his visits, he noticed Al-Ali’s paintings. The writer was the owner of Al-Horiya magazine. Kanafani recognized the talent of Naji Al-Ali and encouraged him to continue to develop his abilities. In 1961, he decided to publish Ali’s drawings in his magazine.

Few years later, Ali moved to Kuwait and began his professional career at the Al Tale’ah weekly magazine. He had a variety of responsibilities at this magazine. He was a secretary, editor, reporter, and journalist. When he was working in the magazine, he understood that cartoons were the most powerful ways for the expression of his thoughts. The other distinctive feature of his creativity was an emphasis on poor people. Ali believed that the fate of the poor was the most terrible and full of misfortunes. He said, “The poor people are those who suffer, are sentenced to jail, and die without shedding tears.”

After being in Kuwait, Ali returned to refugee camps in Palestine. He was surprised to find out that people were not living with the idea of Palestinian liberation with the same desire and willingness to act. In 1982, Lebanon faced the attack of Israeli forces. Again, Ali had to move to another place and leave his native home. This time, he happened to be in ships with other Palestinian people.

For several years of movements and changes of locations, Ali returned to Kuwait. The famous Arab edition, Al-Qabbas, accepted him as an employee. Naji Al-Ali always introduced extreme criticism addressing particular leaders. Some political groups did not like his activity and cartoons. The cartoonist received a variety of threats and warnings. As a result, he had to leave the country. He began working in the London branch of that newspaper.

Assassination

Naji Al-Ali’s settlement in London was a final destination in his life. On 22 July 1987, Ali was moving towards his office. He received a shot in the face immediately in front of his office. He was delivered to the closest hospital in the area. Then, he was replaced in the department of neurosurgery at Charing Cross Hospital. Later, it was found out that some witnesses saw “Ali being approached by two men — aged twenty-five to thirty, with olive complexions — when one of them drew a gun and shot him at point-blank range on the right side on his face.”

Naji Al-Ali was not killed immediately. He was in the coma for almost six weeks. After the death, all writers, reporters, and journalists started to look for the answer to the most disturbing question — “Who killed Naji Al-Ali?”. The number of accused was immense as well as various testimonies claimed that different influential people wanted Ali to be dead. A day after Ali’s death, The Observer published an information accusing the PLO of killing Naji Al-Ali. According to The Observer, Ali received a threatening call not long before his death. The message of the call was to “correct the attitude”.

An unknown voice also told: “Don’s say anything against honest people, we will have business to sort you out.” It is estimated that the caller was a leader of the PLO — Yasser Arafat. However, Ali neglected the threat and published his last cartoon. In general, he received approximately one hundred warnings and threats during his life.

Two general theories about Ali’s killers were the most widespread. According to the first supposition, the leader of the Palestine Liberation Organization, Yasser Arafat, was the initiator. This view was extremely controversial as far as many people considered that no Palestinian would kill another son of the country. Still, Ali criticized Arafat’s hegemony within the state. The other opinion was much more accepted. According to it, the Israeli Mossad (secret service) organized the assassination of Naji Al-Ali. This version was popular because Israel was an enemy of Palestine, and such a conclusion was logical. The British police found a suspected man who could be the hitman of Ali. This man was known as a member of the PLO assassination group in London. Thus, the evidence demonstrated that Arafat was more likely to be the culprit.

The last important thing about Ali’s assassination concerned his burial. The cartoonist was buried in London, and many people did not understand the reasons. Naji Al-Ali was devoted to his native country and refugee camp, so many individuals believed that it would be better to bury him in Palestine. According to Lemelle, two possible reasons were introduced. First, authorities were afraid that the masses’ reaction to the death might be unpredictable or even aggressive. The second estimation was very controversial. “Naji Al-Ali’s burial in London testified to his controversial independence, his contentious and critical ideological position vis-à-vis the Arab regimes and his insistent ‘representation’ of all the Arab people, who, like the Palestinians, were systematically exploited.”

Cartoons

The art of drawing was the most important for Naji Al-Ali. As has been already mentioned, he started his artistic career with drawing on the walls of cells. Naji Al-Ali realized that art could serve as a powerful means of sharing experiences and revealing the truth. With the help of art, artists depict the everyday lives of people as it is. They uncover a reality about life and picture it from the new angle so that everyone can see what is hidden behind.

Cartoons of Al-Ali were of great significance for the Palestinian people. Even more, they influenced numerous people who lived in the Arab world. Al-Ali’s cartoons did not serve their original aim — to entertain readers. Al-Ali used the art of drawing cartoons for rendering political messages. He was a political activist who understood the inequalities and untold secrets of governments, political regimes, and activities of authorities. Naji Al-Ali expressed his personal opinions and feelings in his cartoons.

However, his opinions represented the life condition of numerous refugees who lived in refugee camps after the conflict in 1948. The massive expulsion of the Palestinian people and loss of home were central themes in his works. Naji Al-Ali drew the life of the poor. He wanted to reflect all sufferings and misfortunes of his people. He also referred to other nations drawing oppressed people in the Arab countries and worldwide. Ali’s cartoons were predominantly pessimistic. However, some of them inspired people to believe in better future for Palestine and its residents.

The primary theme of Al-Ali’s works is political and social criticism. Thus, he was a merciless when he censured the arbitrariness of officialdom and ruling powers in the Middle East region. He addressed taboo issues, and his bravery was unique in this respect. Naji Al-Ali ridiculed political leaders, uncovered the pretense and hypocrisy of the rich, and demonstrated the situation and life of the poor people. Al-Ali addressed the topic of the corruption of the Arab major powers.

He also accused them of acting against the interest of their people and nations. He was not afraid to criticize the United States of America for the backing of Israeli activities. The cartoonist expressed his indignation concerning the foreign policy of the Soviet Union. Thus, he reprobated the Soviet Union’s intention to make use of some of the Arab countries to protect own interests. Naji Al-Ali also reacted to the international relations of the Gulf States and blamed them for the compliance and obedience to the Western states. The distinctive feature of his cartoons was their simplicity. Thus, everyone could comprehend the simple message hidden in the context of the particular cartoon.

Main Characters

Naji Al-Ali created over forty thousand cartoons. The most vivid and significant character in all his cartoons is Handala. He is a ten-year-old boy who observes all inequalities and problems that are typical for the Arab regimes. Handala (often spelled as Handhala, Hanzala) was created in 1969 and since that time became a mute witness.

The significance of Handala cannot be overestimated. He became a sign of the defiance and the unity of the Palestinian people. Al-Ali used to put a signature of his name before introducing Handala. When the boy became a well-known symbol, Ali used him instead of the signature. The name of the boy is translated as “bitter fruit”, and he is a representative of people who live in refugee camps. The age of the icon is autobiographical. At the age of ten, Ali was expelled from his native village.

It is relevant to cite the words of Naji Al-Ali about Handala. He wrote, “The child Handala is my signature everyone asks me about him wherever I go… His name is Handala, and he has promised the people that he will remain true to himself. I drew him as a child who is not beautiful; his hair is like the hair of a hedgehog who uses his thorns as a weapon. Handala is not a fat, happy, relaxed, or pampered child. He is barefooted like the refugee camp children, and he is an icon that protects me from making mistakes.” The example of the cartoon with Handala is as follows:

In this cartoon, Al-Ali criticizes the Arab regimes. In the cartoon, the man says that he will shave his beard if the Arab regimes aim at the liberation of Palestine and other people. One can see the second picture and come to a logical conclusion.

Fatima is the only female character in Al-Ali’s cartoons. She serves as an embodiment of Palestine, Lebanon, and all refugee camps. She struggles for the freedom of Palestine and makes sure that nobody gives up. The distinctive feature of Fatima is that she always wears a house key around her neck. The next picture is a cartoon with Fatima. It is devoted to refugees.

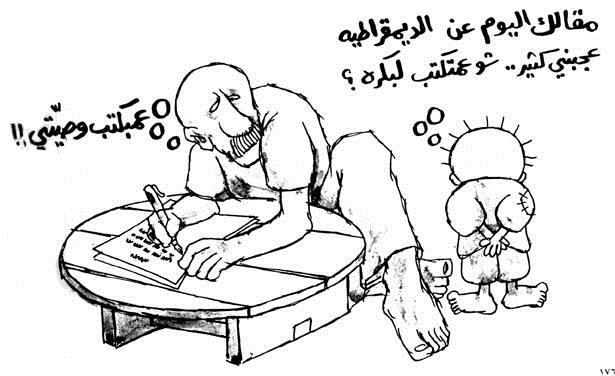

Al-Zalama is another character of Naji Al-Ali. He is a man who represents poor people. He usually wears shabby clothes and has a miserable appearance. Naji Al-Ali created that character to depict all poor people who live in Palestine. Al-Zalama is used to demonstrate the hard life in refugee camps or the injustice of the Arab regimes. In the following cartoon, Handala tells the man that his recent article about democracy is fascinating. The boy asks about the next article about the man. However, the man answers that he is writing his will for tomorrow. This cartoon shows that the freedom of expression and the Arab regimes are not compatible notions.

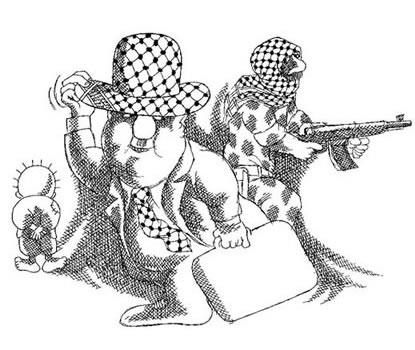

The last character of cartoons is Evil Man. He is a picture of everything negative in the Arab world. An Evil Man is used to personify officials who are interested in their benefits rather than in the development of the country and overall progress. He is depicted as a fat man dressed in the suit who has a stupid look at his face. The following image demonstrates Al-Ali’s vision of the difference between officials and representatives of power and refugees.

Naji Al-Ali’s Cartoon and the Palestinian Identity

The cartoons of Naji Al-Ali and Handala, in particular, became signs of rebellion and fight for Palestine’s freedom. These cartoons motivate people not to give up and remember that they should continue doing everything possible. Al-Ali’s cartoons are often estimated to be a powerful source of the political identity of Palestinians.

Al-Ali’s cartoons, characters, and his personality became icons of the Palestinian upheaval. Gruber and Haugbolle use the term “secular iconography” to describe Al-Ali’s artistic activity from the political and social perspective. Authors write, “In the twentieth century, the original meaning of “icon”, an image preserving the divine, gradually has been secularized to mean representations that inspire some degree of awe — perhaps mixed with dread, compassion, or aspiration — and that stand for an epoch or a system of belief.” Al-Ali uses a variety of symbols and themes that enhance the identity of the Palestinian people.

Naji Al-Ali established the Palestinian identity via the utilization of the secular folkloric symbols. Fatima is a vivid example of the usage of folkloric symbols in drawings. Thus, her embroidered dress and key around the neck are symbols that can be recognized by the Palestinian people. Fatima wears a key from her house with a hope to see his native place again. The key is a figurative symbol of returning to Palestine and ending of the conflict. The key is a Palestinian symbol of home. It is a sign that serves as a reminder of belonging to the particular land.

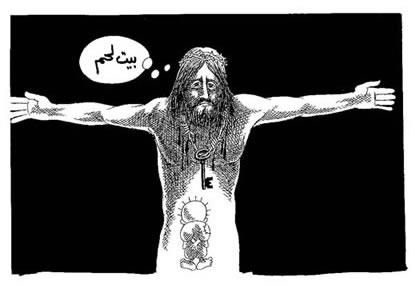

The employment of religious symbols is another way to affect people and whole nations. Naji Al-Ali utilizes both Christin and Muslim religious symbols in his works. The usage of Christian symbols, such as a depiction of Christ, is not typical for the Palestinian artists, due to the drastic differences in these cultures and religions. Still, Palestinians are aware of the story of Jesus Christ and know its significance. The following picture is a cartoon with Jesus Christ.

The Christ is depicted without Crucifixion. He has a key on a barbed wire around his neck as Fatima. That key and barbed wire are used as the Palestinian analogy for the cross and crown made of thorns. Sufferings of Jesus and his life are compared to that of the Palestinian refugees. Thus, Naji Al-Ali takes foreign symbols and puts them in the domestic context. The cartoonist knew ways of addressing his native people and wringing some secret chords in their hearts that inspired them to believe in a better future for Palestine.

Conclusion

Naji Al-Ali was an outstanding figure in Palestine. He was a well-known cartoonist who used his drawing to express indignation about the political authorities and Arab regimes. The main character of his cartoons is Handala — a ten-year-old barefooted boy from refugee camps. He is a mute witness of all inequalities and tragedies of Palestine. Naji Al-Ali contributed significantly to the development of the Palestinian identity and became a symbol of freedom and resistance.

Bibliography

«Al-Ali 2.” Muftah.org. 2015. Web.

“Al-Ali 5.” Muftah.org. 2015. Web.

Al-Arian, Laila. “Naji Al Ali’s Cartoons Still Relevant Today.” The Washington Report on Middle East Affairs 24, no. 1 (2005): 67.

Alkhateeb, Firas. “The Nakba: the Palestinian Catastrophe of 1948.” Lost Islamic History. 2013. Web.

Balfour, Michael. Refugee Performance. Bristol: Intellect Books, 2013.

Fassed, Arjan. “Naji Al Ali: the timeless conscience of Palestine.”The Electronic Intifada. 2004. Web.

Gruber, Christiane and Sune Haugbolle. Visual Culture in the Modern Middle East. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013.

“Jesus.” Handala.org. 2015. Web.

Khoury, Gisele. “Understanding Politics in the Arab World through Naji Al-Ali’s Cartoons.” Muftah.org. 2013. Web.

Lemelle, Sidney. Imagining Home. London: Verso Books, 1994.

Mattar, Philip. Encyclopedia of Palestinians. New York City: Infobase Publishing, 2005.

Najjar, Orayb. “Cartoons as a Site for the Construction of Palestinian Refugee Identity.” Journal of Communication Inquiry 31, no. 3 (2007): 269.

“Palestine Remembers Prominent Political Cartoonist Naji Al Ali.” Palestine News & Information Agency (SyndiGate Media Inc), 2015.

“Refugees 5.” Handala.org. 2015. Web.

“Refugees 7.” Handala.org. 2015. Web.

Totry, Mary and Arnon Medzini. “The Use of Cartoons in Popular Protests that Focus on Geographic, Social, Economic, and Political Issue.” European Journal of Geography 4, no. 1 (2013): 23.

“Who is Handala?” 2015. Web.

“Who Killed Naji Al Ali?”Beyond the Mass Media. 2015. Web.

“1987: Cartoonist shot in London street.”BBC. 2015. Web.