Neuroplasticity Principle Interference

Brain plasticity has a typically favorable connotation when it is about to function in recovery. However, plasticity can also serve as a roadblock to modifying behavior (Kleim & Jones, 2008). The ability of a particular neural circuitry’s plasticity to interfere with the development of new plasticity or the expression of preexisting plasticity within that same circuitry is known as interference. As a result, learning could be impeded (Kleim & Jones, 2008). Even though a variety of noninvasive cortex stimulation techniques applied before or during skill training may enhance motor learning, other types may interfere with learning. For instance, transcranial direct current stimulation administered following training decreased the gains in cortical excitability caused by training.

Robbins Experiments of Spatial Learning

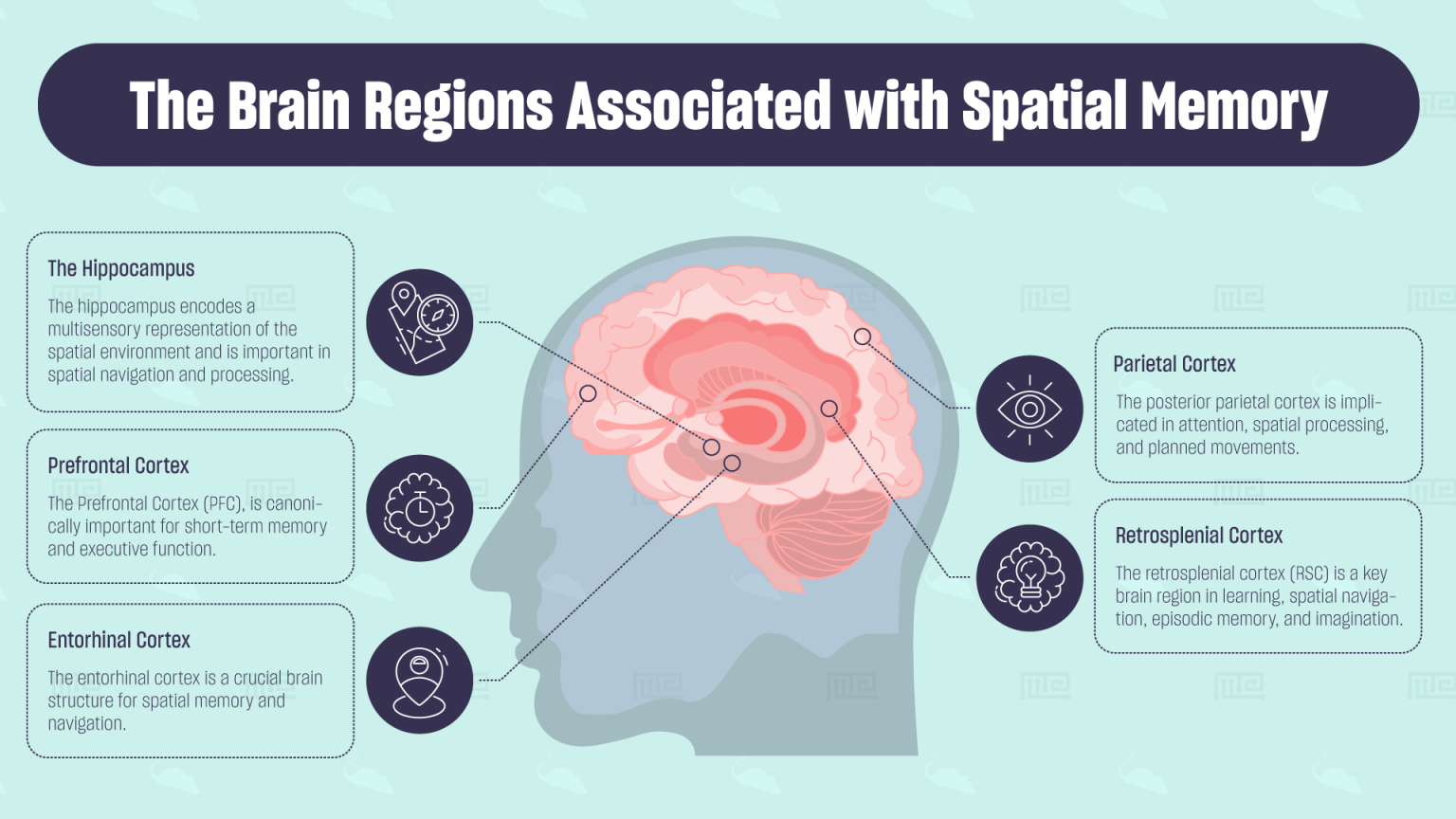

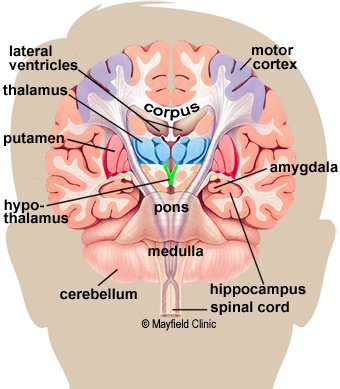

The hippocampus, a part of the brain important for spatial learning, has been found to become saturated with synaptic potentiation in rodent spatial learning tests, which has been demonstrated to hinder subsequent learning. The behavioral cues promoting plasticity during training are enhanced by the additional stimulation. Therefore, it seems sensible that synchronizing training with stimulation increases performance (Kleim & Jones, 2008). Outside of a training environment, stimulation may not only interfere with the consolidation of memories but also lead to plasticity that is uninfluenced by behavioral cues and is, therefore, harmful to performance. This has particular significance for the use of adjuvant stimulation to speed up recovery after brain injury.

Additionally, it is feasible for behavioral experience to influence the plasticity of remaining brain regions in a way that will obstruct the best potential behavioral recovery. In contrast to more challenging but ultimately more successful compensating methods learned during rehabilitation (Kleim & Jones, 2008), brain trauma survivors may establish undesirable habits that make compensatory tactics simpler to conduct. These techniques may be employed considerably more often and with more haste than those recommended during therapy (Kleim & Jones, 2008). After brain injury, it could be simpler to develop some compensatory behaviors (Kleim & Jones, 2008). Rats with minor unilateral somatosensory cortex lesions acquire a novel proficient reaching task with a less forelimb with fewer apparent aiming mistakes than undamaged rats, and this is linked to more pronounced neuroplastic alterations in the contralesionally motor cortex.

Stimulation Outside Training Experiences

Transient virtual lesions of the motor cortex in humans also improve some hand functions when they are ipsilateral. However, relying too heavily on less vulnerable modalities might potentially accentuate impairments (Kleim & Jones, 2008). In rats with unilateral infarcts, early skill training on the ipsilesional limb was found to significantly deteriorate subsequent performance and decrease the use of the compromised forelimb, suggesting that it may have led to learned nonuse. These self-taught compensatory methods may cause plasticity when they are maladaptive, which will need to be addressed with further rehabilitation and other therapeutic modalities (Jones, 2017). Therefore, a therapy that improves one ability may interfere with the performance of another, which is another reason to take interference effects into account.

Principle Application to Therapy

Neuroplasticity, also known as neural plasticity, is the brain’s capacity to alter, change, and Adapt its form and operation during a person’s life and in response to environmental factors. The emphasis of this systematic review is on neuroplasticity that results from treatment-induced neural alterations. These alterations in brain function have been linked to alterations in synaptic strength, neuronal excitability, neurogenesis, or cell death, as well as changes in dendritic development or neuronal sprouting, which may be seen by neuroimaging after therapy (Grefkes & Fink, 2020). Promoting transference to neighboring abilities and avoiding interference from maladaptive alterations can be achieved through the targeted use of certain skills in functional activities with sufficient intensity, repetition, and complexity. Because substrates tend to become better with continued usage, skills may be promoted in response to targeted practice.

MIT (Melodic Intonation Therapy as a Form of Interference)

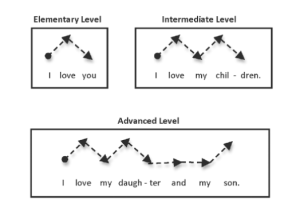

Individuals claim the following recommendations for use in clinical practice for treating patients with nonaffluent aphasia: For people with noneffluent aphasia in subacute and chronic phases, MIT is a successful treatment strategy, especially for improving overall informativeness of speech (CIUs), but also repetition and naming to a lesser extent (Jones, 2017). Due to the special mix of rhythm and pitch and their link to right hemisphere structures, MIT can be more successful than SRT or conventional hierarchical cueing therapy models for enhancing the informativeness of speech in people with noneffluent aphasia v. MIT therapy can promote neuroplastic alterations in important language regions and right hemisphere homologs (Jones, 2017). The ability to identify adaptive or maladaptive behaviors in persons receiving MIT therapy can be determined by longitudinal neuroimaging research.

The review’s findings also support research applications: Intensive behavioral therapy, like MIT, may have an impact. Target speech measures’ behavioral results can be influenced by one’s neurophysiology and, in turn, certain neurophysiological changes. Neuroimaging 54 procedures and the recovery stage are the main elements determining result data, and both significantly impact the patterns of brain remodeling in response to MIT treatment (Grefkes & Fink, 2020). Longitudinal imaging techniques may shed further light on the long-term effects of lateralization and habituation on plasticity. Longitudinal neuroimaging analysis during therapy offers the ability to identify patterns of adaptive restructuring and support therapists in their efforts to forecast behavioral outcomes for use in decision-making.

MIT Treatment Activities

The vast range of favorable behavioral outcomes connected to shifts in total lateralization may be attributed to the individual’s level of recovery. Individuals in subacute stages tended to exhibit good results for increased correct language lateralization, whereas chronic cases tended to show more favorable outcomes for increased left language lateralization. In addition, strongly reduced left hemisphere activation occurs during the first few days to two weeks after onset. Recruitment of homologous correct hemisphere language areas occurs within the first year. According to Saur’s hypothesis of language recovery, most subacute patients should have a rightward shift, whereas most chronic patients should have a leftward change.

Longitudinal Imaging

Future research should evaluate neurological and behavioral changes in response to MIT in a larger cohort utilizing uniform neurological and behavioral evaluation techniques to overcome the limitations mentioned in this study (Lu & Lu, 2021). Understanding how MIT functions in the brains of neurotypical people learning strange languages or under circumstances that facilitate dysfluency would also be helpful for this field of inquiry. Utilizing more accessible neuroimaging techniques might help maximize cost efficiency. Functional near-infrared spectroscopy (fNIRS), a noninvasive method that uses fiber optic lamps placed extracranially to detect hemodynamic response during a particular activity, is one such method.

Melodic Intonation Therapy (MIT) for Severe Aphasia and apraxia

MIT helps in statistical power; researchers can better understand the mechanism of neuronal remodeling. MIT is ideal for kids with speech apraxia.

Recovery from aphasia typically happens in three phases:

- Broca’s aphasia.

- Wernicke’s aphasia.

- Global aphasia.

Structural Changes Associated with MIT

As expected, the proper AF and SLF were the regions of FA of WM with the highest structural modifications, whereas IFOF and UF also had some changes. This finding raises the possibility that the recovery assisted by MIT may include these white matter fiber tracts (Jones, 2017). It is feasible that MIT might improve crucial white matter pathways for language and speech by targeting the AF and SLF tracts.

Additionally, it has a complicated nature that is influenced by the features of the lesions. Using a covert naming task. After therapy, one patient showed reduced activity in brain areas that are right hemisphere homotopic to left hemisphere language regions, responding well to treatment (Jones, 2017). The right hemisphere homotopic to the left 48 hemisphere language areas of the second patient exhibited increased activity following therapy; in contrast, this patient did not react well to treatment.

MIT Effects

Furthermore, MIT causes a rise in the left hemisphere’s activity that supports language, which helps nonaffluent aphasia patients exhibit a considerable improvement in their behavioral reactions (Jones, 2017). Their finding supports the widely held belief that it is less effective than the left hemisphere and should only be used in the absence of left hemisphere structures (Jones, 2017). Since the patients did not have aphasia diagnoses that were homologous, they were not suitable for comparison of behavioral outcomes.

The earlier reviews presented contradictory results. While one study reported a positive association between FA and CIUs, another discovered a negative link between FA and CIUs. One more recent study was also included in the current review. They observed a significant increase of FA in the right SLF, IFOF, and UF related to improvements in speech output (Jones, 2017). Conclusions regarding the nature of WM plasticity in response to right 46 hemisphere WM changes are discussed because two of the three articles included in the present review reported a positive correlation between FA of WM, and one reported a strong negative correlation.

Future Research

As was already indicated, this mismatch, which is the total number of fibers against the level of anisotropy, may be connected to the various DTI analysis methodologies. Research in the future using indicators often guarantees proper data synthesis (Jones, 2017); WM should be carried out utilizing standardized analytic methodologies. Another explanation is that Wan’s study used Chinese (Jones, 2017), a tonal language that might have had a special effect on neural reorganization.

References

Chilla, S. (2022). Assessment of developmental language disorders in bilinguals: Immigrant Turkish as a bilectal challenge in Germany. In Handbook of Literacy in Diglossia and in Dialectal Contexts (pp. 381-404). Springer, Cham. Web.

Grefkes, C., & Fink, G. R. (2020). Recovery from stroke: current concepts and future perspectives. Neurological research and practice, 2(1), 1-10. Web.

Jones, T. A. (2017). Motor compensation and its effects on neural reorganization after stroke. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 18(5), 267-280. Web.

Kleim, J. A., & Jones, T. A. (2008). Principles of experience-dependent neural plasticity: implications for rehabilitation after brain damage. Web.

Lu, S., & Lu, S. (2021). Understanding intervention in fansubbing’s participatory culture: A multimodal study on Chinese official subtitles and fansubs. Babel, 67(5), 620-645. Web.