Introduction

Can such a conventional and cheap material as paper tubes have value? This question should be asked prior to a discussion of Shigeru Ban’s designs because the approach this architect takes is far from conventional. In the wake of discussions about environmentalism, as researchers have started paying closer attention to significant shifts in the use of resources for sustaining human activity, Ban chose to combine simplicity and utilitarianism in architecture while resisting the appeal of using expensive materials.

The purpose of this paper is to analyze the significance of Ban’s designs with the help of Paper Church as an example. The building was chosen for examination due to its unique combination of contemporary design, the use of low-cost materials, and the humanitarian intentions of rebuilding a vital community building that suffered damage from a natural disaster.

Who is Shigeru Ban?

Shigeru Ban is a renowned Japanese architect who gained worldwide recognition for his innovative work with unique materials, in particular with recycled paper such as cardboard. The approach that Ban takes in his work leads to the creation of outstanding objects of architecture in the category of sustainability. Ban’s quote “I don’t like waste” summarises his approach toward design – while the architect’s work follows the principle of sustainability, the artistic concepts are never compromised.

Because the preservation of nature and the reuse of materials have been Shigeru Ban’s focus, a large part of his work has been dedicated to humanitarian efforts such as restoring shelters, offering protection and comfort for communities in need, and providing support for people around the world who have suffered from the devastating effects of both man-made and natural disasters.

Shigeru Ban was born in 1957 in Tokyo at the time when Alvar Aalto, the father of International Modernism, was at the peak of his career. Thus throughout his education and career, Ban was heavily influenced by the monumentalism of the modernist style. In 1985, one year after Ban returned to Japan upon his graduation from Cooper Union in New York, the architect undertook his first serious project, designing and building screens for Emilio Ambasz’s exhibit.

The most important point to mention regarding the screens is that they were so spectacular that they outshow the actual exhibition, which subsequently led Ban to choose paper architecture as the primary means of his artistic expression. He started using cardboard tubes for display stands, which became so popular that they were included in the exhibition of Alvar Aalto’s work. The use of unconventional materials was especially justified by the lack of a budget for architectural work as well as the recyclability of cardboard. Importantly, Ban did not limit the use of paper materials to exhibitions and developed his work to include furniture and larger architectural pieces.

Before creating the famous Takanori Catholic Church (1995) in Kobe, Shigeru Ban created several pieces of architecture that should be mentioned. Among these works were the Curtain Wall House in Itabashi (Figure 1), Paper Arbor in Nagoya (Figure 2), Furniture House in Yamanashi, MDS Gallery, Library of a Poet, and several others.

The Paper Church

The significance of Takatori Catholic Church, also known as the Pater Church, has long been apparent. Located in Nagata-Ku, Kobe, the initial structure was founded in 1927 and completed in 1929. The structure has always served as a gathering place for people to connect with each other. For example, in the 1980s, children of Vietnamese refugees gathered in a small room attached to the church to do their homework with the assistance of volunteer teachers from the neighbourhood or local universities.

On January 17, 1995, the Takatori Church was involved in the Great Hanshin earthquake, which destroyed the original structure of the building as well as others that surrounded it. In order to recover and deal with the devastating effects of the earthquake, the community came together to rebuild the church and restore their place of gathering.

Shigeru Ban decided to make a pro-bono contribution to the restoration of the church. His initial idea behind the design was to capitalize on the use of unconventional materials for creating a low-cost and easy-to-assemble structure that volunteers could easily assemble and disassemble. Ban’s contribution is valuable because the architect understood the utilitarian purpose of the church and wanted to provide victims of the earthquake with a place of worship. Despite the fact that the structure was intended to be temporary, it was only disassembled in 2005. With all leftover materials sent to a city in Taiwan to adhere to the principles of sustainability and low waste.

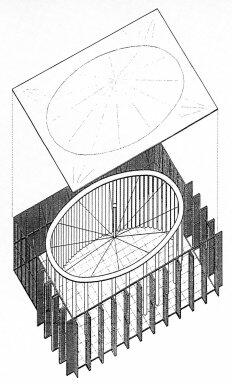

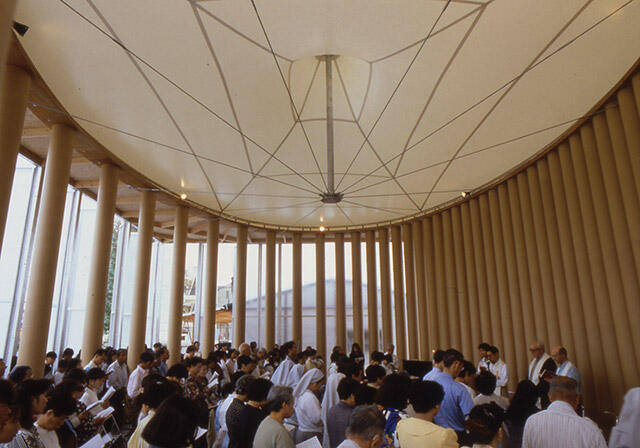

As already established, Shigeru Ban’s innovative approach toward low-cost architecture implied the use of conventional materials for unconventional purposes, and the Takatori Church was no exception. The plan of the building (ten by fifteen meters) was enclosed with polycarbonate sheeting. Within the enclosure, the architect created an elliptical pattern made from fifty-eight paper tubes, which were very easy to transport and assemble quickly (Figure 3).

The tubes were five meters high, three hundred and thirty millimetres in diameter and were intended to support a tent-like roof that was made from Teflon-coated fabric. In order to create a backdrop for the altar as well as to form a screen for some storage, the paper poles were located with closer spacing than in the rest of the ellipse. On the side opposite the altar, the poles were intentionally placed with wider spacing to allow for better entry to the church as well as to ensure an enhanced continuity between the exterior and the interior (Figure 4).

The elliptical pattern of the paper poles was inspired by Bernini’s church designs; however, the beauty of the paper church was associated with the modesty of its materials, which differ significantly from those that Bernini used. The materials were collected as donations from local companies, and the construction of the entire design was completed within five weeks, which is an extremely reasonable timeframe.

In addition to the characteristics of the church’s interior, it is also important to discuss whether the structure was connected to nature. From the outside view, the Paper Church is a rectangle building with floor to ceiling shutter doors to protect the fragile paper structure inside from wind and rain. There is a grass plane on which the church is located, which creates a connection between the structure and nature. Additionally, there are some trees situated toward the back of the building (Figure 5).

The use of Teflon-coated fabric instead of glass in the floor-to-ceiling doors is justified by the fact that the architect wanted to make the project as low in cost as possible. In addition, using fabric was much easier during the building’s assembly.

Ban’s Design Significance

Ban’s Paper Church is a reflection of the architect’s evolution with respect to such ideas as modernism, environmentalism, and humanitarianism. The use of paper tubes can be traced in many of Ban’s creations regardless of their size and scope. While the poles were used as a cost-effective means for restoring a community’s place of worship, they were also used for the Japan Pavillion at Expo 2000 in Hannover or for the packaging of Henry Giraud Champagne. Therefore the significance of Ban’s designs is associated with creating high-end architecture, furniture, and other items from accessible materials, which points to the humbleness of the architect.

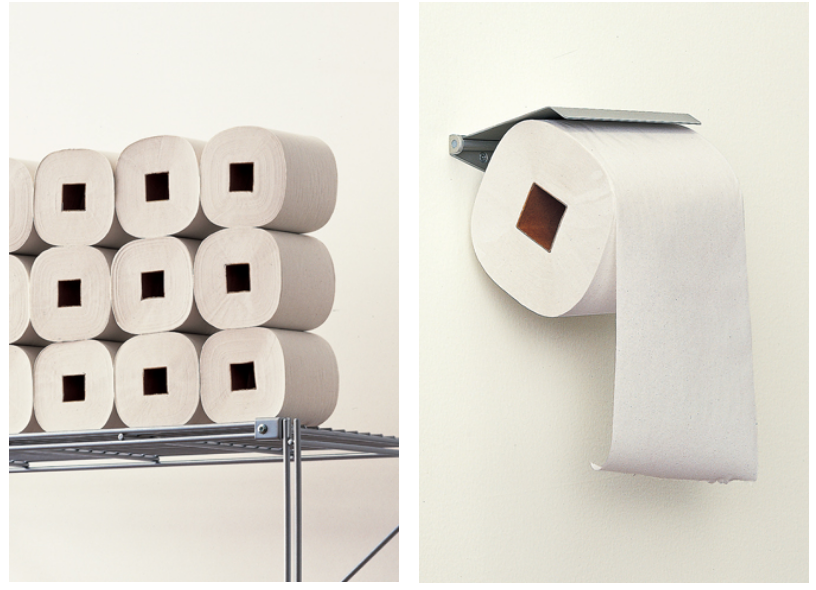

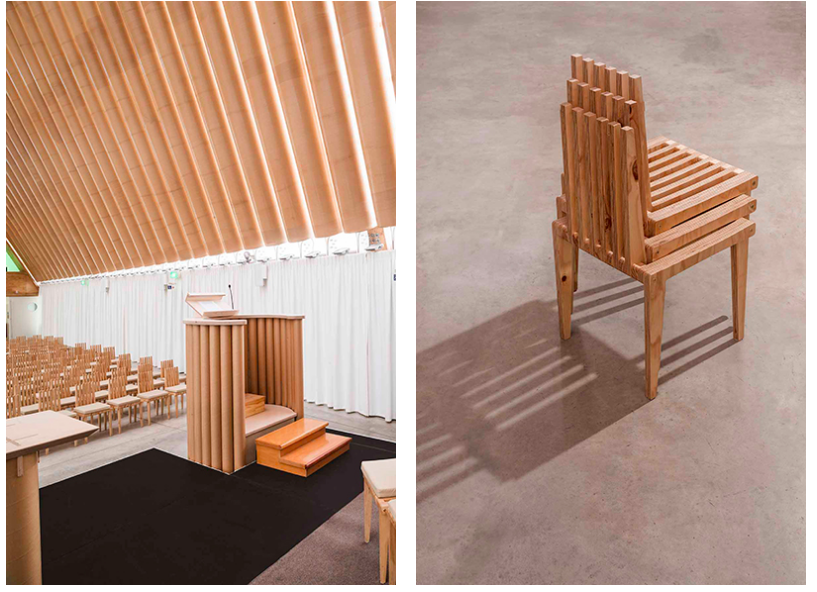

Another crucial point to mention about Ban’s approach toward design is the utilitarianism of the objects that he creates, and the Paper Church is a clear example of this approach because the initial intention was to restore the building and make it usable again. Other examples of combining utilitarianism, modern design, and low-cost materials include The Paper Tube and Plywood Stool (Figure 5), Toilet Paper (Figure 6), Cardboard Cathedral Furniture (Figure 7), Hualin Temporary Elementary School (Figure 8), and many others.

Humanitarian efforts that Ban pursued are integral to the architect’s philosophy. Along with the use of materials such as paper, Shigeru Ban is renowned for his unique approach toward designing new pieces of art, which builds on his compassion and care for others. In 2014, he founded the Voluntary Architects Network in order to apply modern knowledge in the sphere of design to providing housing and shelter to communities in need (for example, where disasters have struck) around the world.

While the organization was created in 2014, the humanitarian intentions of Ban date back to the 1990s and the Paper Church in particular. Apart from the Takatori Catholic Church and the Hualin Temporary Elementary School that have previously been mentioned, Shigeru Ban designed Paper Log Houses in Kobe, Paper Emergency Shelters for the UNHCR in Rwanda, Paper Log Houses in India, Paper Concert Hall in Italy, the Paper Partition System for the great Japan Earthquake and Tsunami in 2011, Container Temporary Housing in Onagawa, and many more.

Concluding Remarks

The Paper Church, designed by Shigeru Ban, is among the clearest examples of the architect’s ideology of combining modern design, low-cost materials, and utilitarianism. With the initial intention to make it possible for community members in Kobe to recover their place of worship from a devastating earthquake, Ban created a simple but unique architectural piece that represents the main idea behind all of his work. Shigeru Ban is appropriately referred to as a ‘people’s architect.’ for his respect for low-cost materials whose use may strike some as counter-intuitive.

Instead of using concrete, marble, stone, or any other solid and expensive materials, Ban embraced the simplicity of paper in the form of cardboard tubes in order to respond to community needs worldwide. When a humanitarian disaster strikes, Ban is always ready to design and build a temporary structure to shelter communities and provide them with an opportunity to rebuild their lives.

Bibliography

AD Editorial Team. “The Humanitarian Works of Shigeru Ban.”Arch Daily. Web.

Cardboard Cathedral Furniture. Digital image. Shigeru Ban Architects. Web.

Curtain Wall House. Digital image. Image Archtonic. Web.

Corkill, Edan. “Shigeru Ban: ‘People’s Architect’ Combines Performance And Paper.”Japan Times. Web.

Hualin Temporary Elementary School. Digital image. Shigeru Ban Architects. Web.

Gottlieb, Nanette. Language and Citizenship in Japan. New York: Routledge, 2012.

Pallasmaa, Juhani, and Tomoko Sato. Alvar Aalto: Through the Eyes of Shigeru Ban. London: Black Dog Publishing, 2007.

Paper Arbor. Digital image. Shigeru Ban Architects. Web.

“Paper Church (Takatori Yokai), Kobe-shi, Japan.”Galinsky. Web.

Paper Church from the Outside. Digital image. Pinimg. Web.

“Paper Church Kobe.”Architect Magazine. Web.

Paper Church Poles. Digital image. Artribune. Web.

Paper Church Shigeru Ban. Digital image. Images Lib NCSU. Web.

Paper Tube and Plywood Stool. Digital image. Shigeru Ban Architects. Web.

“Shigeru Ban Architects.” Shigeru Ban Architects. Web.

“Shigeru Ban.”Design Indaba. web.

“The Materials of Shigeru Ban.” World Architects. Web.

Toilet Paper. Digital image.Shigeru Ban Architects. Web.

Zuckerman, Heidi Jacobson, and Claude Bruderlein. Shigeru Ban: Humanitarian Architecture. New York: Aspen Art Press, 2014.