There is little doubt that an effective approach to management depends on numerous components, of which behaviour is paramount since the human factor has a direct impact on the process of interaction. In this context, one should not only monitor strategies and solutions to improve one’s knowledge and skills but should also take into account other persons and the peculiarities of their personalities that influence professional communication (Okoye 2015). At the beginning of any interaction, it is critical to recognise a person’s personality type and organise one’s actions correspondingly in order to reap the desired benefits regardless of individual character traits. In addition, it is equally essential to have control over all conversations, including the difficult ones, and to provide appropriate feedback. In this way, behaviour and its management becomes a complex and multidimensional factor.

In this paper, a reflection on the key topics of the unit is given along with my personal reactions to and perceptions of the information. For me, working with different personalities in various aspects, having difficult conversations, and structuring the most effective feedback turned out to be issues of great interest. The report describes the most frequent challenges in each of these three areas. Moreover, definitions, theoretical frameworks and their assessments, and recommendations are given. The results of the personality tests I have taken are interpreted and explained through the lens of management, work opportunities, and communication. Finally, a conclusion concerning the role of behaviour in management is given.

Working with Different Personalities

The large body of recent literature on personality and management issues points to the fact that both researchers and managers regard these two factors to be integral parts of the formula for success (Bakker, Tims, & Derks 2012). As a rule, the following issues are emphasised by researchers: the definition of personality, its characteristics, and various approaches pertaining to personality tests.

The Definition of Personality

As the principal element in the context of cooperation with diverse persons, personality has been studied for a long time. In the broad sense of the term, personality may be defined as a set of steady and distinctive properties that help distinguish an individual from other people (Wilson 2013). In fact, personality is comprised of a wide range of values, attitudes, memories, social relationships, habits, knowledge, and skills that a person has (Hislop 2013). It is possible to examine personality in relation to all realms of life, including work performance.

What usually demonstrates researchers’ involvement in personality studies is their focus on behaviour. Such a focus may be explained by the fact that behaviour is the only available indicator of personality, an idea that seems incredibly valuable. As far as I have observed, stability as the primary characteristic of personality is often criticised, and thus behaviour becomes the most important index because it tends to be changeable; as a result, personality may not be considered a permanent entity because time alters some of its features. I can state with confidence that this knowledge formed the basis for my orientation in personality studies and testing.

Personality Traits

Personality may be described in terms of its traits. There are many frameworks and models that serve to describe different versions of the relationship between work and personality, and the most widespread model is known as the Big Five. Under this framework, five personality factors—namely extraversion, neuroticism, openness to experience, agreeableness, and conscientiousness—are believed to be the most suitable factors for predicting an individual’s behaviour. Indeed, it has been emphasised that the Big Five model is especially advantageous to assess employees’ working efficiency (Judge et al. 2013). In my opinion, this framework has two major strengths: its simplicity and the opportunity it offers to describe a wide range of human personality traits systematically. However, this model depends on the use of subjective information, meaning that one cannot rely on it alone. Indeed, I have learned that a manager should always use more than one model.

Personality Tests

Apart from the Big Five, there are many other models designed to evaluate a person’s personality traits and arrive at a conclusion concerning his or her work performance. Whether it is a pencil-and-paper test or a computer instrument that is used, the results of psychometric tests may be applicable to various companies and employees. Such tests prove to be particularly effective when it is necessary to assess a person’s skills, capabilities, and personality and to predict his or her future behaviour (Kline 2013).

Created on the basis of everyday language, Cattell’s 16PF personality questionnaire is used to describe personality traits by means of specific factors, including, for instance, the following: warmth, rule consciousness, liveliness, and openness to change. Each of them is assessed on a specific scale (Nikolaou & Oostrom 2015). Because the purpose of the test is to identify the main structural components of personality and provide information about mental health, it can be effective in different contexts. I have noted that the model’s exact questions and answers, as well as its accurate system of scoring, are advantageous, but at the same time, there is no guarantee that a participant is telling the truth. Consequently, this test could be used as one of the measures of personality, but these serious limitations should be considered.

The Eysenck Personality Inventory/Questionnaire is another type of test that managers and employers may use. Its aim is to measure extraversion-introversion and neuroticism-stability as the pervasive and independent dimensions of personality that explain a wide range of behavioural patterns and motivations. As Eysenck (2012) states, this model incorporates the idea that individual differences are to be taken into account, along with the concepts and methods of experimental psychology that can provide valuable materials and conceptual tools for constructing a theoretical system.

Since psychological issues are relevant in most spheres of life, this model can be extended to other areas as well—and work behaviour and performance ideally fit the description. As I understand it, a combination of either introversion or extraversion with a certain degree of emotional stability is most desirable: the detected personality traits account for a person’s behaviour or, at the very least, help predict his or her possible reactions with a sufficient degree of accuracy. Having learned the main features of this test, I suppose I will use it in future. Although only the current stage of personality development is examined in this model, it is important to evaluate a potential employee and his or her abilities.

In addition to these tests, self-reported (mixed) emotional intellect (EI) tests are very popular among researchers who study work performance, leadership, and teamwork. In spite of the numerous approaches and different settings in which this theory is applied, emotional intelligence is understood in almost the same manner: it is defined as the ability to perceive emotions; to use them as an instrument in addition to thinking and understanding; to effectively control them in order to grow both intellectually and emotionally; and to give other individuals the opportunity to do the same (Wilson 2013).

Some authors believe that this approach is more advantageous in comparison with other frameworks including the Big Five; however, several similarities may be traced among them because mixed EI strongly overlaps with several well-known psychological constructs, such as ability EI, self-efficacy, self-rated performance, conscientiousness, emotional stability, extraversion, and general mental abilities (Joseph et al. 2015). Just as any framework does, this approach also has its strengths and weaknesses: although EI knowledge enhances social effectiveness, decreases bullying, and protects people from destructive behaviour, it simultaneously can be used to manipulate an individual and obtain personal benefit. I think that EI development is vital and that all employees should acquire basic skills in this area; otherwise, social communication will always be associated with obstacles or even conflicts. I entertain the possibility that I will use EI knowledge and encourage other people to do so as well, especially if they seem to lack these skills.

The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator is also helpful in examining personality traits and behaviour. One of the main advantages of this approach is that in can be utilised to improve the quality of work in terms of team development, conflict management, leadership, promotion, and stress management. For example, recent research has revealed that particular types of personalities, namely extraverted and sensing types, prove to be the most successful of all 16 types and take less time to climb the career ladder (Furnham & Crump 2015). However, in my view, the most considerable advantage to this framework is that it also gives the opportunity to understand which personality types interact in more effective ways. With this knowledge, managers will be able to improve team composition and achieve goals with minimum hassle.

Because I developed a particular interest in this approach, I completed the Myers-Briggs personality test and discovered that I belong to the extravert and feeling types of personality. I achieved the following results.

Humanmetrics Jung Typology Test™

You’re Type

ESFJ

Extravert(53%) Sensing(19%) Feeling(28%) Judging(19%)

- You have moderate preference of Extraversion over Introversion (53%)

- You have slight preference of Sensing over Intuition (19%)

- You have moderate preference of Feeling over Thinking (28%)

- You have slight preference of Judging over Perceiving (19%)

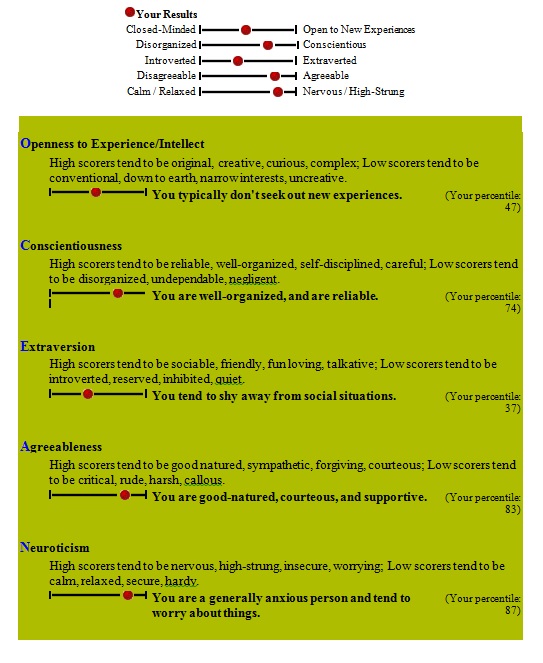

I also took the Big Five model test since it is the most popular instrument, and I obtained the following results.

Big Five model test results

Having increased my knowledge of personality and its influence on work performance and communication in the context of teams, supervising others, and leadership, I can state that I am more aware of the ways in which my behaviours can impact different personalities. Now I am certain that it is necessary to use at least two of the tests mentioned above to identify personality type, and the best choice of test depends on the purpose and the context of work. For instance, the Eysenck Personality test will be useful as an individual assessment tool, while the Myers-Briggs Type test results can be helpful in avoiding problems in communication and interaction.

When a person’s major personality type is known, I will be able to behave accordingly: for example, I can give tasks that demand independent work, assiduity, and attention to detail to those staff members who are more introverted. Moreover, I have improved my knowledge of my own personal strengths and weaknesses by means of these personality tests, even though some information was not entirely accurate. I can see that I should make use of my organised nature and my ability to listen and be sympathetic: I give clear instructions and understand the needs of people. I also realise that I should overcome my weaknesses like nervousness and reluctance to look for new experiences in order to succeed. By doing so, I can develop my skills and improve my behaviour and approach to management

Conversation is the primary form of human interaction, and the sphere of work and business communication is no exception (Cornelissen et al. 2015). An effective manager should be able to conduct a dialogue with any type of personality. When difficulties arise, one should take measures to reach consensus. In terms of conversations, feedback is one of the central components because the data provided by an individual’s network (e.g., supervisors, peers, clients) is necessary for that person to effectively understand, perform, and develop in his or her role (Campion et al. 2015). Therefore, it is important to study different types of conversations, including difficult ones, and draw attention to feedback as an important aspect of cooperation and the cornerstone of improvement.

Difficult Conversations and Effective Feedback

Types of Conversations

When examining personality types and contexts, the different types of conversations should also be taken into account. Rational negotiators tend to rely on facts and logical assumptions, and such conversations should be based on accurate data from credible sources (Ingram 2013). In comparison, managers should also be familiar with emotional conversations that develop trust and identify team relationship dynamics (Liu & Maitlis 2014). Finally, there are hybrid conversations that include elements of both types. I believe that the hybrid type is the most advantageous because both logic and emotions catalyse people.

Conversations can be further classified according to purpose: dehydrated talks, disciplined debates, intimate exchanges, and creative dialogues. The first type refers to ritualised exchanges with no real interest in understanding each other; the second one pertains to high-level analytical rationality with little emotional involvement; intimate exchange implies personal issues that are often inappropriate at work; and finally creative dialogues are notable for perceiving facts through the lens of emotions (Collis 2016). Thus, it is necessary to recognise the purpose of any conversation and to identify the degree of emotions and facts involved.

Difficult Conversations

To organise a good conversation, one should keep in mind several issues: doubts and questions should be encouraged, the space and time should be appropriate, and procedures and regulations should be updated. Moreover, all parties should control their biases (Eisler 2015). However, a lack of difficulties in the conversation cannot be guaranteed.

As far as I have observed, difficult conversations can also take different forms, which presents substantial problems since each case is unique. A manager should not only find the optimal solution but also respect the interests of all stakeholders, demonstrating it by means of proper feedback (Johnston & Marshall 2016). In this regard, one should consider a wide range of factors. Difficult conversations are often rooted in bad news, negative feedback, performance administration, company changes, downsizing, conflict situations, and so on (McCarthy & Milner 2013). Moreover, several of these factors are usually combined. As a result, behaviours will be different in every case.

The Role of Self-Awareness

Self-awareness may be described as understanding how one’s emotions and feelings affect one’s reasoning, thinking, and interacting with other people (Daft & Marcic 2013). Many researchers regard self-awareness as the key element that helps not only in difficult conversations but also in multiple communication situations. An effective negotiator or mediator must recognise not only the economic, political, and physical aspects of difficult conversations but also the emotional tenor. Self-awareness is the primary tool for productive emotional management, such as concerns of appreciation, affiliation, acceptance, status, and role (Kelly & Kaminskiene 2016). Self-awareness and feedback are intertwined with emotions and feelings, but they promote manifold decisions related to difficult conversations. Low levels of self-awareness are likely to bring harm since a person might deceive him or herself and transfer this attitude to the management of human resources. Thus, the risks of treating employees as objects grow.

In my opinion, self-awareness is essential for any manager because it helps one apply the principles of collaboration and attention to experience. It is self-awareness that shapes a person’s behaviour, and the results of any activity directly depend on it.

Recommendations

For difficult conversations and feedback, some recommendations may be given. Although different researchers provide different frameworks, there are some similarities. First and foremost, it is necessary to pay attention to the matter at hand: issues outside of the framework of the situation should not be discussed under these circumstances (Bens 2012). The manager should explain his or her ideas adequately and deliver the message using facts and relevant examples. Another tip is to focus on the situation rather than persons or their characteristics (Simons 2013). One should be prepared for the possibility of extreme emotions and still be able to give constructive feedback (i.e. expressing one’s opinion politely and taking into account other people’s intentions and interests).

Overall, the information about difficult conversations and relevant feedback has been useful. I have reconsidered some aspects of my behaviour, especially my attitude towards the causes of misunderstanding and communication difficulties. I used to think that an individual approach should concentrate on the personal differences between people, which led to difficult conversations and even conflicts. However, I have come to understand that some external factors (e.g., termination talks) also have a substantial impact and that managers must highlight the situation over the course of the conversation while applying knowledge of personality implicitly.

Another valuable piece of knowledge that I have gained concerns the relationship between self-awareness, self-deception, and feedback. Low levels of self-awareness result not only in a distortion of the truth but also an improper reaction. An employee who receives such feedback will hardly understand it. Consequently, he or she will be confused and cannot be assessed objectively, which will only add to the existing problems. This idea will be helpful in future because it pertains to common situations. I will change my behaviour in accordance with events, current challenges, and constructive feedback.

Conclusion

In conclusion, managers should take into consideration numerous facts and implications and plan their actions in compliance with personality types and contexts of conversations. Moreover, feedback is a valuable instrument that indicates either the effectiveness of the current approach or the need for change. As one of the most significant issues in terms of communication and interaction, behaviour has a powerful impact on the way employees, teams, and organisations perform. Deeper knowledge of personality, its types, its assessment, difficult conversations, and efficient feedback will help me change my behaviour and make it more suitable to particular situations. With this knowledge, I am sure that I will communicate more effectively and will improve my approach to controlling difficult conversations by making use of situation-centeredness and relevant feedback.

Reference List

Bens, I 2012, Advanced facilitation strategies: tools and techniques to master difficult situations, John Wiley & Sons, Hoboken.

Campion, MC, Campion, ED, & Campion, MA 2015, ‘Improvements in performance management through the use of 360 feedback’, Industrial and Organizational Psychology, vol. 8, no, 1, pp.85-93.

Collis, R 2016, Why conversational culture matters to you, Web.

Cornelissen, JP, Durand, R, Fiss, PC, Lammers, JC, & Vaara, E 2015, ‘Putting communication front and center in institutional theory and analysis’, Academy of Management Review, vol. 40, no. 1, pp.10-27.

Daft, RL & Marcic D 2013, Building management skills: an action-first approach, Cengage Learning, Boston.

Eisler R, 2015 A conversation with Peter Senge: transforming organizational cultures. Interdisciplinary Journal of Partnership Studies, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 2-16.

Eysenck, HJ 2013, Personality structure and measurement (psychology revivals), Routledge, New York.

Furnham, A & Crump, J 2015, ‘The Myers-Briggs Type Indicator (MBTI) and promotion at work,’ Psychology, vol. 6, no, 12, p.1510-1515.

Hislop D 2013, Knowledge management in organizations: a critical introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford.

Ingram, R 2013, ‘Emotions, social work practice and supervision: an uneasy alliance?’, Journal of Social Work Practice, vol. 27, no. 1, pp.5-19.

Johnston, MW & Marshall, GW 2016, Sales force management: leadership, innovation, technology, Routledge, New York.

Joseph, DL, Jin, J, Newman, DA, & O’Boyle, EH 2015, ‘Why does self-reported emotional intelligence predict job performance? A meta-analytic investigation of mixed EI’, Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 100, no. 2, pp. 298-342.

Judge, TA, Rodell, JB, Klinger, RL, Simon, LS, & Crawford, ER 2013, ‘Hierarchical representations of the five-factor model of personality in predicting job performance: integrating three organizing frameworks with two theoretical perspectives’, Journal of Applied Psychology, vol. 98, no. 6, pp. 875-925.

Kelly, EJ, & Kaminskiene, N 2016, ‘Importance of emotional intelligence in negotiation and mediation’, International Comparative Jurisprudence, vol. 2, no. 1, pp. 55-60.

Kline, P 2013, Personality: the psychometric view, Routledge, New York.

Liu, F & Maitlis, S 2014, ‘Emotional dynamics and strategizing processes: a study of strategic conversations in top team meetings’, Journal of Management Studies, vol. 51, no. 2, pp. 202-234.

McCarthy, G & Milner, J 2013, ‘Managerial coaching: challenges, opportunities and training’, Journal of Management Development, vol. 32, no. 7, pp.768-779.

Nikolaou, I & Oostrom, JK 2015, Employee recruitment, selection, and assessment: contemporary issues for theory and practice, Psychology Press, London.

Okoye, NV 2015, Behavioural Risks in corporate governance: regulatory intervention as a risk management mechanism, Routledge, New York.

Simons, R 2013, Seven strategy questions: a simple approach for better execution, Harvard Business Press, Brighton.

Wilson, FM 2013, Organizational behaviour and work: a critical introduction, Oxford University Press, Oxford.