Introduction

Since its origin, the relationship between the photographic image and the past has captured the scholarly interest of numerous cultural and literary critics, all of whom seek to analyze the extraordinary power that a particular photograph may have to conjure the past viscerally and immediately. Some photographs develop an emblematic status of an individual, or an event of global significance such as the Holocaust. A particular photo can be so emotionally arresting that it retains an essence of its subject and the circumstances of the photo for a century after it was taken, and invites the viewer to seek a virtual experience of the past within its frame.

Walter Benjamin discussed this phenomenon in Selected Writings when he said “no matter how artful the photographer, no matter how carefully posed his subject, the beholder feels an irresistible urge to search…a picture for the tiniest spark of contingency, of the here and now, with which reality has…seared the subject, to find the inconspicuous spot where in the immediacy of that long forgotten moment the future nests so eloquently that we, looking back, may discover it” (Benjamin 510). Similarly, in Susan Sontag’s influential book On Photography, the critic notes that while photography often depicts odious acts such as murder, atrocity or sexual assault, it nonetheless simultaneously lives in two worlds – the contradictory space between imposition and detached objectivity. In Sontag’s words “using a camera is not a good way at getting at someone sexually. Between the photographer and the subject, there has to be distance. The camera doesn’t rape or even possess, though it may presume, intrude, trespass, distort, exploit and at the farthest reach of metaphor, assassinate…all activities that can be conducted with some detachment” (Sontag 13). Ashley La Grange wrote that “despite being modern, photographs are mysterious. Photographs are not interpretations like writing and handmade images. Photographs seem to be pieces of reality that one can own” (La Grange 30). The sense of reality that photographs impart will occupy a large part of this discussion; the reality of the past, in particular, is of special interest, as is “photography’s connection to death, and thus the power of photographs as media of mourning” (Hirsch 256).

Often the most powerful photographs contain opposing elements, and the restless energy produced by the concurrence of these elements within one frame is the same vibrancy that pierces and provokes the viewer when he encounters the photograph. Marianne Hirsch writes of photographic images as cultural relics that ferry the chasm between generations when she writes “the relationship of children of survivors of cultural or collective trauma to the experiences of their parents, experiences that they ‘remember’ only as the narratives and images with which they grew up, but that are so powerful, so monumental, as to constitute memories in their own right” (Hirsch 9). Similarly, a “photograph may also evoke a place to inhabit, a return to the home where separation no longer counts,” although the paradox of simultaneously having and not having will often be experienced more acutely when the viewer recognizes that the photograph depicts a life long past (Wagstaff 284).

This quality of the photograph image – the capacity to stop time while simultaneously holding an original expression of emotion and the raw, gut experience of reality renders it one of the most powerful tools of communication. “The act of viewing a photograph…specifically an atrocity photograph…can wound the viewer and cause drastic personal consequences, essentially those associated with trauma” (Pane 38).

The problem of photography is twofold: the problem of representation, and the presumption of reality that the photographic images elicits in the viewer – the pervasive belief that a photograph depicts a referent, a real “how it was,” as opposed to a framed composition with an author and a point of view, a version of reality through the specific psychological lens of the photographer. As Behr et al explain, “amongst the numerous turns which academic history is alleged to have undergone recently, that of the pictorial or visual turn has denoted a marked change in attitude by academic historians in the way they are prepared to think seriously about the possibilities and problems of images as historical sources and about the role the visual played for people in the past… The new respect with which historians treat visual evidence – not as subservient but as equal to text – has been a long time coming, as the concept of turn implies” (Behr et al 425).

Photographic images very often subvert the intellectual, critical distance attributed to written texts, simply because they are assumed to be real. As Kattago writes, “photographic images shape historical memory [and]…furnish authoritative evidence to the past” (Kattago 99). However, recent critical insights highlight that “cultural approaches emphasize…the active, protean aspect of culture as lived experience: meaning depends… not only on intentions and circumstances of production but crucially also on mediation and the reception of texts and images – that is, on the spectator’s or reader’s frame of reference” (Behr et al 426). Herein lies a crucial area of analysis regarding the photographic image – that of a coded power symbol from the past which often finds its mirror in the viewer’s present frame of reference. Oftentimes, the coded power symbols revealed in the photograph from the past in fact remain unchanged in the viewer’s present; thus they provide evidence of the seamless continuation of power structures across time. As Behr et al note, “analysing visual evidence…helps reveal how power was constructed and disseminated” and in many cases, maintained into the present time (Behr et al 427).

According to Kattago, the problem of photography occurs when photographs from the past are viewed as a “pure symbols divorced from their particular historical context” (Kattago 99). In many cases “photographs symbolize… truth, evidence, and above all, [the] moral certainty” of the photographer, not to mention his or her power position in relation to the subject (Kattago 101). An obvious example of this occurs in photographic images of female bodies and atrocity photos. “Photography promises power by offering to make truth visible – all is knowable in its gaze. It unites the visible and the invisible, a presence and an absence. Woman is obsessively caught not only as the silenced object of that possessing and empowering gaze, but as its very sign” (Pollock 90). Similarly, atrocity “photographs shock insofar as they show something novel…Once one has seen such images, one has started down the road of seeing more – and more. Images transfix. Images anesthetize…At the time of the first photographs of the Nazi camps, there was nothing banal about these images. After thirty years, a saturation point may have been reached,” not to mention a level of comfort with murder and sexism in the viewer that remains unchallenged (Sontag 21).

Although the photographic image depicts a real person, it is no less illusory by virtue of the illusion of the past itself. Namely, the past remains a fiction, a composite, a mental projection in the mind of the viewer that pertains to a time in history that no longer exists; it cannot be otherwise, since experience demands more than imagination – it demands a living body. But even that is not the true essence of the exchange that occurs between the present viewer and the past subject; no two viewers will have the same interpretation of the period of history that the subject sits in, and the viewer’s emotional involvement with the photograph (or lack thereof) depends entirely on his personal and cultural relationship with the time of history and the events depicted.

The viewer then does not relate ever directly to the subject in the photograph – she relates to her own idea about that subject, and about that period of history that the subject lived in and the events that the photographs depicts. “What you think of as the past is a memory trace, stored in the mind, of a former Now. When you remember the past, you reactivate a memory trace – and you do so now. The future is an imagined Now, a projection of the mind. When the future comes, it comes as the Now. When you think about the [past], you do it now. Past and future obviously have no reality of their own” (Tolle 50).

Similarly, images from the past that trigger some form of emotional resonance between the viewer and the subject do so because something in the mind of the viewer remembers some piece of information that he has stored in his memory related to the period of history that the subject occupies. The explanation behind why this particular piece of information exists in one viewer’s mind and not in another’s remains entirely personal and cultural. Thus, the photograph speaks directly to “the questions of how we remember and what is rendered as history amid an understanding of the role played by the image in mediating memory and history” (Sturken 10). The photograph represents the nexus point between the personal and the cultural history of the viewer; as such, “the role of the photograph in depicting and producing the past as a means to deconstruct identity and as counter-memory” becomes paramount (Sturken 10).

Photographic images therefore host the eternal interplay between illusion and reality, and both states exchange roles depending on the third variable: the viewer. “Photography provides the illusion of evidence, of the objective facts of an event. Due to this demonstrative power, photography possesses a truth-telling aspect that traditional art does not. But because photography validates historical events, they contain the potential to become the authoritative representation of the past” (Kattago 96). The hand of the artist is obvious in other pictorial representations such as paintings and films. Not so with photography; photographs bias toward the real, and they often do so independent of their creators. This illusion of unadulterated, unedited reality persists because a photograph, in the very basic sense, depicts something, something that apparently happened. That something involved someone that apparently existed; however because it is a photograph from the past, the only evidence we have of this event is the photograph itself, which may or may not represent the truth of the event or the truth of the persons portrayed, since the situation and the actors are all long dead. As Susan Sontag explains, “photographs furnish evidence… The picture may distort; but there is always a presumption that something exists, or did exist, which is like what’s in the picture.” (Sontag 3). In addition to the illusion of the photograph, there remains the illusion of the past itself.

Aims and Objectives

The primary aims and objectives of this study are to evaluate the connection between the emotional state of the viewer and how the photographic image generates meaning in him, based on his personal and cultural reference point at the time of viewing. In order to accomplish these aims and objectives, a preliminary discussion of the nature and main characteristic of photography becomes necessary – namely – why do people take photographs? What drives the desire to capture a moment outside of time? Why this need to interrupt time in the human animal, Benjamin asks in The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction? Photographic images may offer memory support, or may provide sentimental access to the dead – as in family photo albums and the like. They also provide access to experiences outside of one’s life – and outside of one’s time of life, as in photographs from the past. However Benjamin likens the nature and main characteristics of photography to the “desire of contemporary masses to bring things closer spatially and humanly, which is just as ardent as their bent toward overcoming the uniqueness of every reality by accepting its reproduction” (Benjamin n.p.).

The photographic image offers a reproduction of lived experience that can be repeated, whereas lived experience of any given moment exists only once. “Every day the urge grows stronger to get hold of an object at very close range by way of its likeness, its reproduction. Unmistakably, reproduction as offered by picture magazines and newsreels differs from the image seen by the unarmed eye. Uniqueness and permanence are as closely linked in the latter as are transitoriness and reproducibility in the former” (Benjamin n.p.). In essence then, the nature and main characteristics of photography – and its main appeal – is that it provides a tool to control and manipulate time, specifically, the lived experience of time, as well as to extend one’s experience imaginatively into other geographic and temporal locations. That said, a photographic image loses something in its manufacture. As Benjamin notes, “to pry an object from its shell, to destroy its aura, is the mark of a perception whose sense of the universal equality of things has increased to such a degree that it extracts it even from a unique object by means of reproduction. Thus is manifested in the field of perception what in the theoretical sphere is noticeable in the increasing importance of statistics. The adjustment of reality to the masses and of the masses to reality is a process of unlimited scope, as much for thinking as for perception” (Benjamin n.p.)

Several techniques exist that enable the viewer to recapture the contemporary problems in the past; however, these techniques must be viewed in their proper context – namely – as mechanisms of imagination. In Benjamin’s analysis, this means that to “articulate what is past does not mean to recognize how it really was. It means to take control of a memory” (Benjamin n.p.). The viewer can only ever recapture an imagined past; the living past cannot be physically achieved. This is not to say that the imagined past will not affect the viewer in the present, and in her physical being – certainly it does. As Benjamin explains, “the conception of the past…makes history into its affair. The past carries a secret index with it, by which it is referred to its resurrection. Are we not touched by the same breath of air which was among that which came before? Is there not an echo of those who have been silenced in the voices to which we lend our ears today?… There is a secret

protocol…between the generations of the past and that of our own (Benjamin n.p.). And yet, this protocol exists as an imagined shared space. However, this study also reveals one technique that enables the viewer to have a direct experience of the past in his present frame of reference, that is, through the recognition and analysis of the power relationships depicted – both explicitly and implicitly – in the photograph from the past.

Background Information

An historical overview of photography understands that photography and history are interrelated. Photography itself represents the material culture of the past and connects further spiritually concepts in the present and future (Edwards 130). The advent of photography transformed the experience of lived reality as well as the experience of the past; photography provided access to “real people” from the past, rather than “artists’ depictions” of people from the past. As Benjamin notes, once photography came into being, “for the first time in the process of pictorial reproduction, photography freed the hand of the most important artistic functions which henceforth devolved only upon the eye looking into a lens. Since the eye perceives more swiftly than the hand can draw, the process of pictorial reproduction was accelerated so enormously that it could keep pace with speech” (Benjamin n.p.)

Conceptually speaking, photographs should be perceived “not only as images but as a series of material practices” that “enrich the interpretive approaches and understanding of the evidential quality of photographs as historical elements” (Edwards 130). Image quality and orientations has a potent impact on the assessment of photographs. These characteristics involve shape, contrast, individual peculiarities that create a specific impression on the viewers (Tinio et al. 166). Barbie Zelizer discusses one example of this concept when she details the experiences of the first photographers allowed into Germany at the end of World War Two:

Photography of the liberation of the concentration camps of World War II is a record in need of attention. The horrors of the camps were photographically depicted in a vast array of circumstances by individuals with varying skills and agendas. From the U.S. Engineering Corps Officer, numbed by a frenzied shuffle that transported him from camp to camp with a camera in his pocket, to the Signal Corps photographer borrowed from Life magazine to bring home the camp…the so-called professional response to the event was simply one of making do, an improvisory reaction to often faulty equipment, bad weather and uneven training and experience… (Zelizer 249; Zelizer 87)

Thus, photographic images that manifest a higher degree of skill remain more likely to generate a powerful emotional effect on the viewer, regardless of whether or not they depict “the truth”. A photographic image with poor production values, though it may depict the actuality of the event and of its subject, will be passed over in favour of a photograph with higher production values, even if the veracity of its depiction of the event and the subject is suspect.

The phenomenon of the photographic image and its relationship to the past then becomes a moving target; it speaks to a complex and dynamic interaction between referent, subject, viewer, numerous other variables associated with the production of the photograph itself, and the illusion of the past. As Buse states, “photography itself is a mode inextricably tied up with loss – the loss of a referent, to which, paradoxically, it promises access” (Buse 253). Similarly, according to Banfield, the problem of photography exists not only in the limitation of lived experience of but also in the insufficiency of language itself. The viewer attempts “to find the linguistic form capable of recapturing a present in the past, a form that it turns out spoken language does not offer. This now-in-the-past can be captured not by combining tenses but by combining a past tense with a present time deictic: the photograph’s moment was now” (Banfield 175).

Problem Statement

On the one hand, the photographic image is a reflection of the opinions and evaluations of the viewers that react to its identity and integrity. On the other hand, the photographic image reflects its author’s individual and cultural perspective, agenda and main idea. To reconcile these two dimensions is sometimes impossible (Price 117). Where the past is concerned, similarly, the photographic image represents an imagined referent, a referent that cannot be accessed (Buse 253).

Argument

Instantaneity in Lacan’s model remains crucial to the provision of narcissistic satisfactions and the formation of the ego in its imaginary direction, and this remains true also of the ego’s imagined experience of static time, as supported by the photographic image (Buse 34). “Photography, then, is analogous to the mirror in the way that it provides for the ego an illusion of unity,” not to mention an illusion of the unity of lived experience in time (Buse 34). The photographic image creates a unity of time, place, referent and lived experience that even our own eye does not possess. “Our eye is never seized by some static spectacle, is never some motionless recorder; not only is our vision anyway binocular, but one eye alone sees in time… In a real sense, the ideological force of the photograph has been to ignore this in its presentation as a coherent image of vision” (Heath 10).

That said, the argument this study pursues is that the illusion of photography can be expressed through its appearance in different ways to a viewer who is capable of changing its meaning by via her emotional and psychological state at the time of observation. As such, the beholder is the one who makes the photographic image everlasting, changing, and outside of time.

Literature Review

Theory is “coherent set of understanding about a particular issue which has been …appropriately verified” (Wells 22). It is primarily based on cultural and intellectual circumstances. The positivist approach is one of the outcomes of these circumstances that provide the explanation of photography from the perspective of social science and aesthetic.

Where photography is concerned, current theories and discussions involve the different stages of reproduction, including capture of the original subject. In this respect, the photograph can be compared with relics that transfer a physical body through time and space. This interpretation is involved in a psychological image (Modrak and Anthes 171). Psychological and emotional feeling are crucial and the main tasks of the photograph is to render its character in a way that viewers will not impose his own vision on the meaning of the image. Whether or not these tasks are possible is the realm this study explores.

Analysis of Project

The major concept of photography, and the analysis pertinent to this project with regard to the literature review, is the relationship between the photographic image and time. From a historical retrospective, time is the core component of photography (Van Gelder and Westgeest 64). The theoretical framework of this study understands that the photograph “makes viewers aware [of] an experience of time that cannot be experienced through the human eye” (Van Gelder and Westgeest 82). Thus time in the photographic image is necessarily a fiction. The photographic image also “contains” time, in both its present and absent forms; “the photo makes one aware of looking at the past and the distance between now and then…as opposed to a film, which is experienced as presence,” as “moving” time, and therefore not static (Van Gelder and Westgeest 95).

This theoretical framework “leads…to the assimilation of photography and memory, and…the metaphor of death for photography” previously discussed (Van Gelder and Westgeest 95; Hirsch 256). The study also makes use of the theoretical framing of the photograph as “associated with presence over an extended time span because the stillness of the picture renders it a prolonged object of contemplation” (Van Gelder and Westgeest 95). This critical association of the “power of presence of photography with memory…[makes] the past part of the living presence” as a catalyst for the imagined past and its relationship to photography that this study explores (Van Gelder and Westgeest 95).

Findings

What follows in the analysis of nine historical photographs ranging in date from 1890 to 1943. Each photograph depicts a particular period of history alongside a corresponding social or political issue depicted within the photo. These social or political issues and frames of reference persist to this day – thus the “present” depicted in these photos is a shared experience between us the viewers in 2011 and the subjects of these photographs from the past. These social and political issues include subjugation of Native American peoples, child labour, violence and hatred directed toward Jews and valuation of women solely upon the basis of their physical beauty and youth (or lack thereof).

In all of the photos, the “present” depicted in the photograph from the past remains essentially unchanged; in the cases of the photos of Native Americans and the women, for example, over a century has passed, yet the power relationships depicted within the photos endure in 2011.

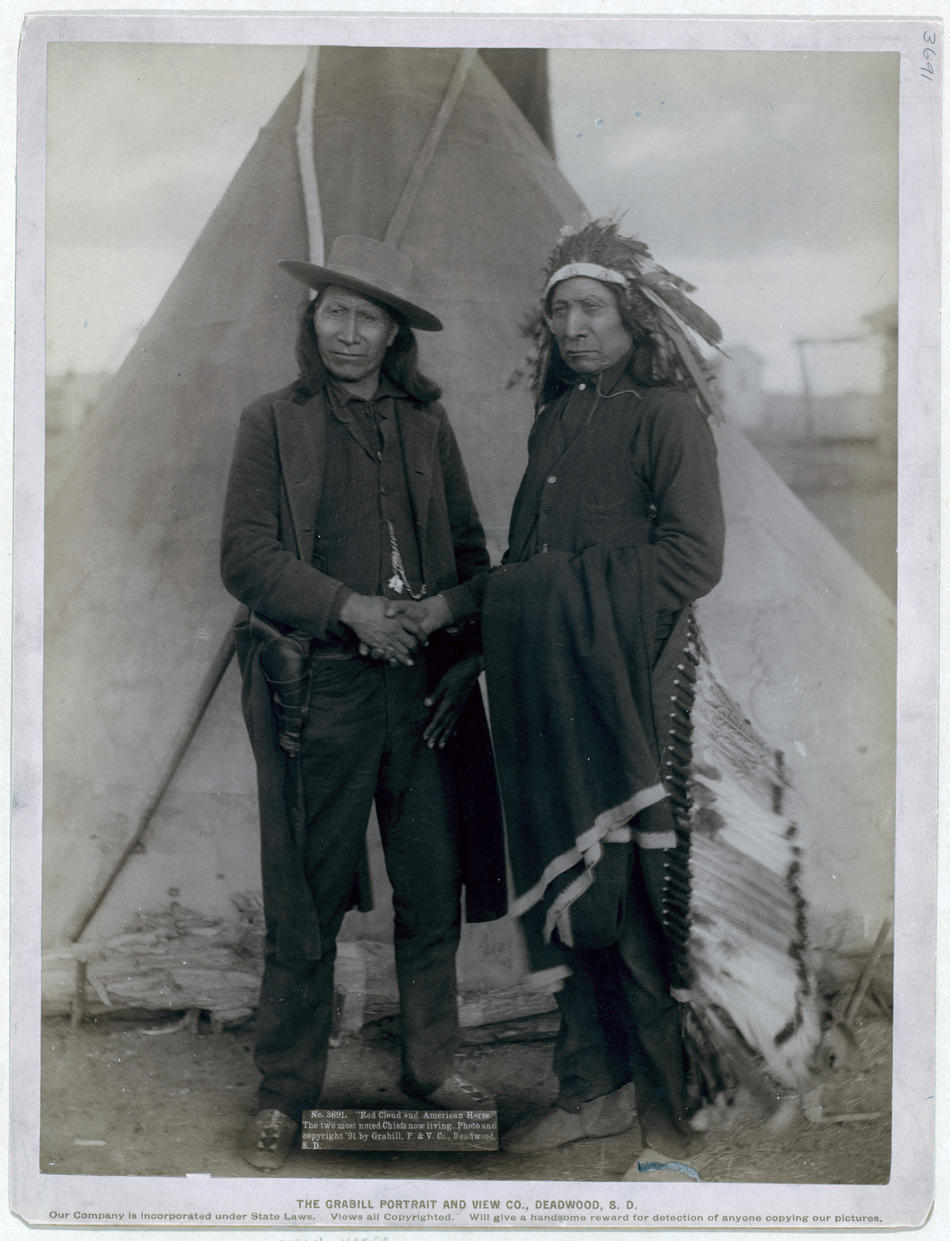

Native American Photos

The first photo, “Little, the Instigator of Indian Revolt at Pine Ridge,” dates from 1890 (Grabill n.p.). Briefly, the Native American resistance to European expansion across the United States at this historical juncture was largely dust. 1890 marked the year that Chief Big Foot and nearly three hundred other Sioux – most of them women and small children – were shot to death by the Seventh Regiment of the U.S. Cavalry during the Wounded Knee Massacre in South Dakota (Brown 523). Historians peg this event as the final bloody event which decisively ended the Indian Wars and crushed all Native American resistance to European expansion across the United States (Brown 523).

In “Little, the Instigator of Indian Revolt at Pine Ridge,” we see Little, an Oglala Sioux warrior best known as the leader of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation Revolt in 1890, squeezed between two European males. Little wears traditional Sioux dress – headdress, war shirt and belt – and he holds a bow and an axe. He stares straight out at the viewer with a hard, imposing, serious expression – it is clear from Little’s facial expression in fact that he is a warrior and a leader of merit and renown. Yet despite his impressive physical appearance, he remains seated. His position in the photograph effectively dwarfs him between the two European males and undermines his presence in the visual effect of the photograph.

In addition to the seated position of Little, the two flanking European males, though they remain unidentified, both lean in slightly toward him, further threatening his position of power. Finally, both of the European males wear facial expressions which speak volumes in regards to the power dynamics at play at the time – power dynamics and ways of relating between Europeans and Native Americans which have persisted into 2011. The male on the right wears a slight sneer, a denigrating expression which seems to mock the Native American man, while the male on the right wears a paternalistic, disapproving expression which appears to be chastising the Native American man. Both men relate to Little less as a human and more as an object – for the male on the right, Little stands as an object of derision; for the male on the left, he stands as an object of censure and pity.

According to Gidley, the framing and composition of the photograph must not be viewed as accidental on the part of the photographer, John Grabill, but a planned and orchestrated political and social act intended to create a representation of the Native American that served European interests (Gidley 24). In Gidley’s words, “photographers were employed in all but the very earliest phases of white westward expansion, from exploration to the official geological…surveys…to the initiation of Western tourism. Whether a photographer…freelanced as an entrepreneurial studio owner in a new town (which was the situation for John Grabill in Deadwood, South Dakota), he…was fully part of the process of conquest. Indeed, the pictures made in the course of this process were often, in turn, used to boost it…This means that the photographs of Indians produced during and by this westering process should be seen for what they were: images of conquest and dispossession” (Gidley 24).

The photographers who came to the contested lands at this time in history were themselves victors, thus the perspective of victory collared the documentation of the Native Americans the photographers encountered. As Kattago notes, so called documentary photographs always contain expectation, “the expectation of those photographers; in what they expected to find, what they discovered, and what they actually found. [And] …the expectation already prejudiced the photographic eye. They did not simply capture reality “as it was,” but also created it (Kattago 97).

Thus, the subjugation of Little which Grabill arranged and photographed in this example functioned as a political and psychological tool to shape the attitudes of the westering Europeans toward the Native Americans as they settled the United States – namely – as a proud yet powerless race which would give them no trouble. “Photography not only depicted Native Americans but also helped to define them. That is, photography was one among a battery of powerful technologies ranged against indigenous peoples struggling for survival in a landscape that was frequently rich in natural resources, often beautiful, and always contested. Photography was itself, of course, the first of the mass media, and as such it prepared the way for cinema and television; with respect to Indians, we might say that photography established tropes of representation that would be followed, sometimes more influentially, by these latter forms of communication” (Gidley 21).

The second photo, entitled “Red Cloud and American Horse, the Two Most Noted Chiefs now Living,” was also taken by Grabill one year later in 1891 (Grabill n.p.) Red Cloud, the Native American chief on the left, was the leader of the Oglala Teton Sioux (Brown 165). He wears traditional Sioux clothing, including headdress and moccasins, yet he also wears a European style vest with buttons and a shirt with a collar. American Horse, the Native American chief on the right, was an Oglala Lakota Sioux and married to one of Red Cloud’s daughters (Hyde 184). American Horse wears full European dress, complete with hat, pocket watch and pistol. Only his long hair and moccasins bear witness to his former incarnation as Native American Chief.

The two chiefs shake hands, posed in front of a tipi; in the photograph’s background, the apparition of a small white building that might be a church or a school floats. This image attests to the present day struggle experienced by numerous Native Americans – the pastiche of competing cultures that comprise their identities, one simultaneously negating the other. “With pathways to assimilation to the dominant society blocked, [many Native Americans] have slipped or been forced into cultural marginalization. These groups have lost many essential values of traditional culture and have not been able to replace them with active participation in American society” (Lowinson et al 1125).

Though both these men are chiefs, having reached the zenith of power in their culture, they aspire to assimilate within the dominant culture – the European culture. At the very least, that is what Grabill would have us believe by staging the photograph in this way. The facial expressions of the two chiefs also speak volumes about the power dynamics at play; both chiefs appear reticent, unsure and out of their element. Even though they are family, their handshake feels tentative and weak.

The effect of this photograph demonstrates the present day tenuousness still experienced by many Native Americans in 2011, who feel sandwiched between two cultures – one dominating, the other dominated – and unsure of their place and identity in either. When the viewer witnesses the expression on both chiefs’ faces, she sees that the artefacts from the former culture – the tipi, the blanket, the moccasins – feel as strange and foreign in their hands as the collared shirts and pocket watches.

Child Labour Photos

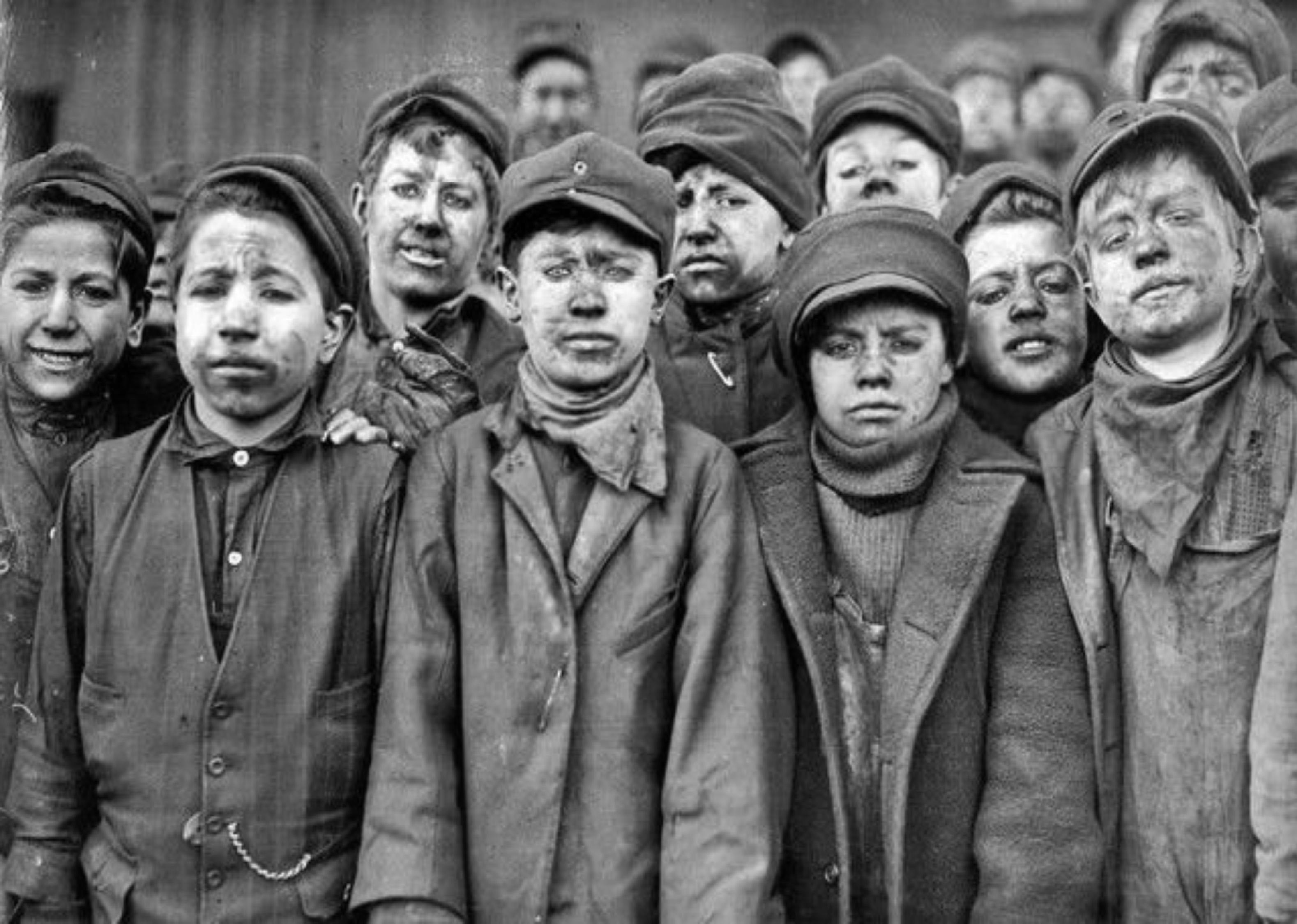

The third photo, “Breaker Boys,” is one of two works featured by the American photographer Lewis W. Hine (Hine n.p.). In 1908 Hine became an investigative photojournalist for the National Child Labour Committee; one year after Congress chartered the group (The History Place n.d.). Between 1908 and 1912 Hine travelled throughout the United States snapping photographs of violations of child labour laws in numerous states (The History Place n.d.) Often Hine found children as young as three years old working long days in hazardous conditions, including mines (The History Place n.d.). In the photo “Breaker Boys,” Hine photographed a group of young boys working in the Pittston, Pennsylvania coal mine (The History Place n.d.).

The boys stand shoulder to shoulder in their work clothes; their faces are smeared with coal dust. Of the nine faces clearly displayed in the photograph, only one child smiles. Several of the children wear suspicious expressions; some frown, some appear afraid, perhaps concerned that posing for this photograph will divest them of their income. All of them are exhausted. A child second from the left has wrinkles on his forehead; his brow is deeply furrowed, similar to that of a man three times his age. Two children on the right of the photograph sneer; it is unclear to the viewer if they are sneering at Hine or at the world itself. Overall, the effect of this photograph furthers Hine’s thesis – that child labour robs children of their youth (The History Place n.d.). The breaker boys are like tiny men; they possess the same mannerisms and world weary fatigue indicative of adult miners, despite the fact that some of them are not yet ten years old.

In the second photo, “Newberry, South Carolina,” Hine captures an extremely young child – likely not more than five years old – working in a mill (Hine n.p.). The child stands dwarfed between two spinning machines, each over a head taller than she is; her clothes are tattered and ripped, she has no shoes on, only stocking feet, and her hair is matted and dishevelled. Her expression portrays a sense of extreme fear; her body is stiff with fear, hands and arm rigid at her sides, shoulders hunched. Her physicality resembles the motionlessness of someone holding their breath. She may be afraid of the machines, afraid of Hine, afraid of the consequences of posing for the photograph, or afraid of the mill oversee who claimed that “she just happened in” in response to Hine’s question of how a child this small could be working in a mill (The History Place n.d.). Whether Hine coached the child to pose in this manner remains unknown; nonetheless, the “present” that we see reflected in this photograph is a terrified child alone in a life-threatening situation.

A hundred years has passed since Hine took these photos. He, all the breaker boys and the little girl are all long dead. However, in 2011 child labour is still a major social and political issue, now global in scope. According to the International Labour Organization’s Facts on Child Labour 2010, 215 million children between the ages of 5 and 14 currently work; of these, 115 million pursue dangerous occupations in hazardous industries such as mining and agriculture (International Labour Office 1). Only one in five of these children actually earns a wage; most are “unpaid family workers,” and 60 per cent of them work in the agricultural industries (International Labour Office 1). The problem occurs most readily in Sub-Saharan Africa, where one in every four children aged 5 to 17 works (International Labour Office 1). Other regions with high rates of child labour include the Caribbean, Latin America and South Asia (International Labour Office 1). Thus, the only real changes that have occurred since Hine photographed the breakers boys and the little girl in the early part of the 20th century is the location of child labour offences and the racial backgrounds of the exploited children. In Hine’s time, the children were poor whites; in our time, they are poor blacks, Asians and Latin Americans. The poverty that gave rise to Hine’s working children still exists today.

The clear social and political agenda demonstrated in the composition of Hine’s photos was able to affect the symptoms of poverty in the United States. Passionately committed to abolishing child labour in the United States, Hine framed these photos with an implicit political message and call to action. “In 1909, he published the first of many photo essays depicting working children at risk. In these photographs, the essence of wasted youth is apparent in the sorrowful and even angry faces of his subjects” (The History Place n.d.). Hine’s goal – to shame lawmakers into enforcing child labour reform – often conflicted with the social mores of his day, namely, that “gainful employment of children of the lower orders actually benefited poor families and the community at large” (The History Place n.d.). In spite of the prevailing social attitudes of his time, Hine’s photos gained widespread distribution and the child labour laws in the United States improved as a result (The History Place n.d.).

In 2011, however, the International Labour Organization reports that child labour decreased internationally by only three per cent between 2004 and 2008 (International Labour Office 1). One possible explanation for the turgid pace of change in child labour regulation may be poverty; another may be the fact that it now happens halfway around the world. However, according to the Child Labour Coalition, in 2011 migrant and season farm workers as young as seven years old work up to 70 hours a week in the United States’ agricultural industry (Child Labour Coalition n.p.). The present represented in these two photos, the grim, desperate poverty that these children embody, remains very much a part of children’s experience in 2011.

Holocaust Photos

Figure 5, “Jewish Resistance Fighters Captured by SS Troops during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Warsaw, Poland, April 19-May 16, 1943,” is a famous photograph that depicts the last moments of two Jewish women and a Jewish man involved in the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising (Polish National Archives n.p.) Photographs that detail the Jewish experience in World War Two remain contentious. As Marianne Hirsh explains, “the Holocaust is one of the visually best documented events in the history of an era marked by a plenitude of visual documentation. The Nazis were masterful at recording visually their own rise to power as well as the atrocities they committed, immortalizing both victims and perpetrators. Guards often officially photographed inmates at the time of their imprisonment and recorded their destruction. Even individual soldiers frequently travelled with cameras and documented the ghettos and camps in which they served” (Hirsch 217).

“Jewish Resistance Fighters Captured by SS Troops during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising. Warsaw, Poland, April 19-May 16, 1943” is of special interest because the subjects in the frame are not corpses; the photo captures them presumably a few minutes before the SS soldiers shot them, and this “frozen moment of impending death forces attention even though people know more than what it shows” (Zelizer 36). The viewer knows the fate of these resistance fighters, yet the present depicted in the photograph itself does not reflect that fate, thus an element of hope infuses the photograph. “Jewish Resistance Fighters Captured by SS Troops during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Warsaw, Poland, April 19-May 16, 1943,” is one of those rare photographs that “make it possible to engage with an event’s visualization without being repulsed by graphic imagery of the dying….And [it] allows viewers to feel as if they are responsibly acting as witnesses to horror, even though they do not attend to its structural conditions, its causality, its purposive nature or its impact” (Zelizer 42). “Jewish Resistance Fighters Captured by SS Troops during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Warsaw, Poland, April 19-May 16, 1943” also contains a rare depiction of Jewish people from the Second World War in poses that do not adhere to the “victim” role that the vast majority of Holocaust imagery places them in.

Many scholars attempt to contextualize the impact of photography on the Jewish experience in the Second World War. For the purposes of this discussion, the focus will be on the work of Marianne Hirsch and Barbie Zelizer. For the most part, Holocaust images fall into clearly defined pictorial camps that carry out polarized psychological functions and processes – victim/aggressor, good/evil, victor/vanquished, etc. These photographs then simply support a more or less “automated” emotional response to the Holocaust in the viewer. Marianne Hirsch’s concern with photographs of the Holocaust in general is that the “photographs have become no more than decontextualized memory cues, energized by an already coded memory, no longer the vehicles that can themselves energize memory” (Hirsch 217). This occurs, Hirsch believes, due to “a striking repetition of the same very few images, used over and over again iconically and emblematically, to signal [the] event” of the Holocaust in the mind of the viewer (Hirsch 217). Thus the viewer does not respond to the present depicted in the photograph itself, but rather to a conditioned psychological and emotional response stimulated by a repetitive series of specific images that denote the Holocaust. The viewer’s experience of the Holocaust therefore becomes utterly divorced from the present depicted in Holocaust photography; it persists, exclusively and unchangingly, in his own mind’s imagined view of the imagined past.

Hirsch calls this phenomenon “postmemory” (Hirsch 220). “Postmemory is meant to convey [a] temporal and qualitative difference from survivor memory, its secondary or second-generation memory quality, its basis in displacement, its vicariousness and its belatedness. Postmemory is a powerful form of memory precisely because its connection to its object or source is mediated not through recollection but through representation, projection and creation – often based on silence rather than speech, on the invisible rather than the visible” (Hirsch 220). While Hirsch’s thesis largely relegates the function of postmemory to survivors and their families, it actually pertains to any person born after the Holocaust. The Holocaust is a young event in the continuum of time; it has shaped culture far beyond its initial reach. The Holocaust is also no longer about Jews and Germans – it now stands as the grand symbol for genocide. As Hirsch notes, Holocaust images and the “postmemory” responses they elicit affect all viewers, regardless of their proximity to the initial conflict (Hirsch 221). Holocaust images trigger an “intersubjective, transgenerational space of remembrance, linked specifically to cultural or collective trauma. It is defined through an identification with the victim or witness of trauma, modulated by the unbridgeable distance that separates the participant from the one born after” (Hirsch 221).

As Hirsh notes, despite the plethora of photographs associated with the Holocaust, “very few of these images were taken by victims” (Hirsch 217). Exceptions include the work of Mendel Grossman and Joe Heydecker (Hirsch 217). However the vast majority of Holocaust images were taken by photographers in power roles – either by the Nazis themselves, by non-Jews or by Allied troops. Similar to the photographs taken of the Native Americans by European photographers, the eye of the photographer, and the psychology behind it, directly shaped a power dynamic within the present depicted in the photographs.

Despite this fact, the photograph “Jewish Resistance Fighters Captured by SS Troops during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Warsaw, Poland, April 19-May 16, 1943” stands as a rare depiction of Jewish people in the face of the Nazi threat who do not appear afraid – this is why it stands out. The present in this photograph, as discussed, captures the three Jewish resistors moments before their deaths. The power of photography, as Hirsch points out, rests in its “evidential force” (Hirsch 224). “The photograph…is the index par excellence, pointing to the presence, the having-been-there, of the past” (Hirsch 224).

These three unarmed Jewish people are critically outnumbered by a herd of SS troops, armed to the teeth; they have a rifle trained on them, the city immediately close to them is rubble and in the background the rest of the city is cloaked in smoke, presumably in flames. The woman at the centre of the photograph has no shoes – she stands with her hands in the air, holding a bag that might be filled with rocks or bread – and she wears socks. Her expression fascinates the viewer, because she almost smiles. There are no tears in her eyes, she does not cower from the SS, and even through her hands are raised in response to the rifle, there is no fear in her face. She focuses her attention on something outside of the frame which appears to amuse her somewhat. The juxtaposition of the slight smile with the proximity of murderous SS troops creates a tension in the photographs that rivets the viewer. What is this woman looking at? And how is it that she can appear bemused moments before she dies? This woman’s expression provides an uncommon view not only of the experience of Jewish people in response to the threat of the Nazis, but also in response to death itself.

The man to the left of her eyes the SS soldier with the rifle. From the expression on his face, the viewer wonders if he might be gauging his odds at escape. The SS soldier watches his colleagues in the background – though he has aimed his rifle at the resistors, the soldier’s attention is focused away from them. The man on the left seems poised to dart off out of the frame; perhaps he will be quick enough to dodge death this time. His attitude fills the photo with hope. Even in the face of the SS in all its horror and brutality, he remains undaunted. He has not surrendered.

The third woman, the woman on the right, offers the quintessential iconic expression of the resistor, not only in her facial expression but in her physical stance also. She stands closest to the rifle; its butt is a mere foot away from her heart. Yet she does not have her hands in the air. Unlike the other two resistors, the woman on the right stands with her arms firmly at her sides. Similarly, her facial expression transmits defiance; she refuses to look at the SS officer, refuses to put her hands up and by the hard set of her jaw, the viewer imagines she will have a few choice words for the SS soldiers before they take her life. The woman on the right is especially interesting because her contempt for the Nazis is so apparent. It is so forceful in fact, that the viewer glimpses the SS soldiers in a way not often seen in Holocaust photographs, particularly from the perspective of the Jewish “victims” – as thuggish fools. Through this woman’s eyes we witness the ridiculousness of the SS officers’ costume, the goonish nature of their kill squad as it attacks starving, defenceless civilians and the overall brutal comedy of the Second World War itself – the homicidal bully at the heart of most fascist dictatorships.

As Hirsch points out, it is “ironic that although the Nazis intended to exterminate not only all Jews but also their entire culture, down to the very records and documents of their existence, they should themselves be so anxious to add images to those that would, nevertheless, survive the death of their subjects” (Hirsch 217). According to the Polish National Archives, the photograph “Jewish Resistance Fighters Captured by SS Troops during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Warsaw, Poland, April 19-May 16, 1943” was taken by a SS soldier who wrote “these bandits offered armed resistance” on the original caption (Polish National Archives n.p.) The fact that the photographer who captured the Jewish resistors moments before their death was in the role of the aggressor offers another insight as to why this photograph is so unique amongst Holocaust imagery. As discussed earlier, the eye of the photographer typically shapes the present depicted within the photograph, as in the example of the photos of the Native American warrior Little, and dictates how the subject will be perceived by the viewer and by history at large (Grabill n.p.). Very rarely does the subject “trump” its composition and turn tables on its beholder. However, certainly in the case of “Jewish Resistance Fighters Captured by SS Troops during the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, Warsaw, Poland, April 19-May 16, 1943,” this is the case. The identity of the SS photographer who described the resistors as “bandits” has been lost to history, yet the photograph he took of them survives, and thrives as a testament to resistance in the face of tyranny (Polish National Archives).

Mug Shots

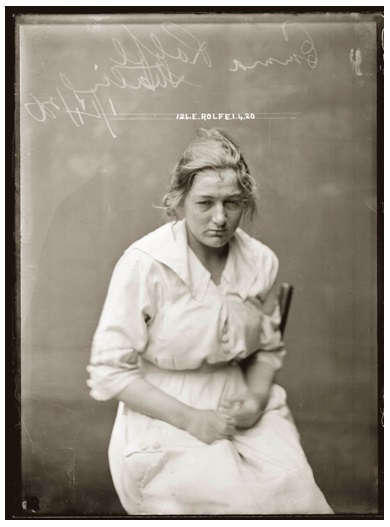

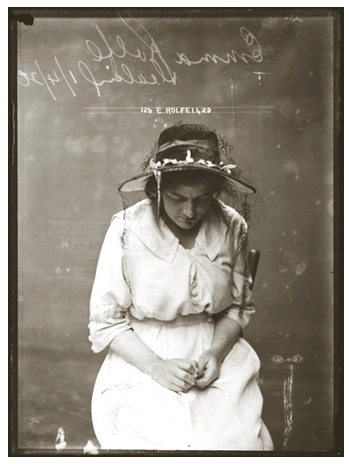

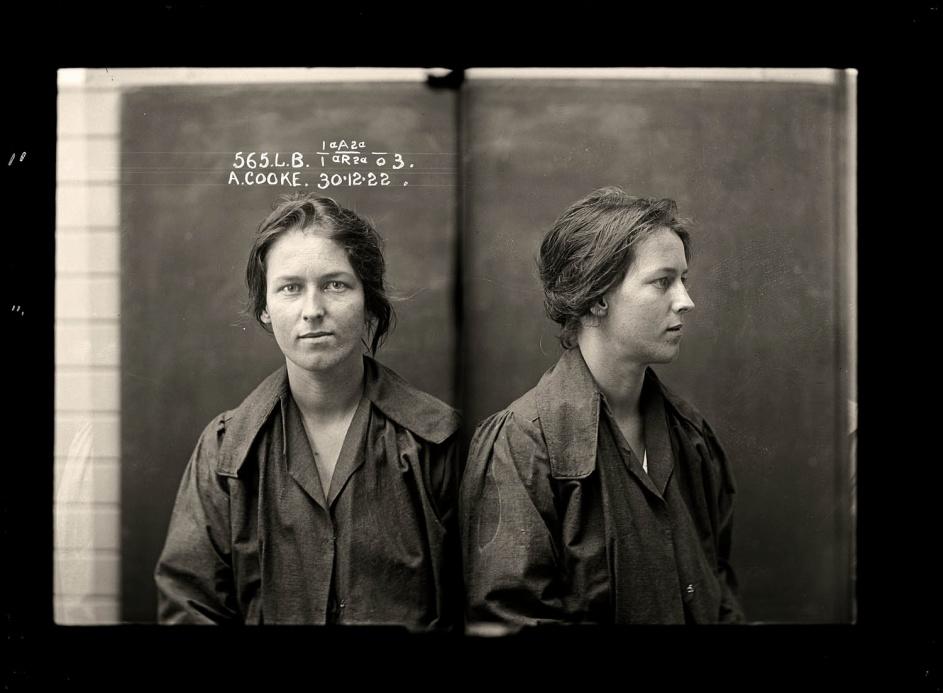

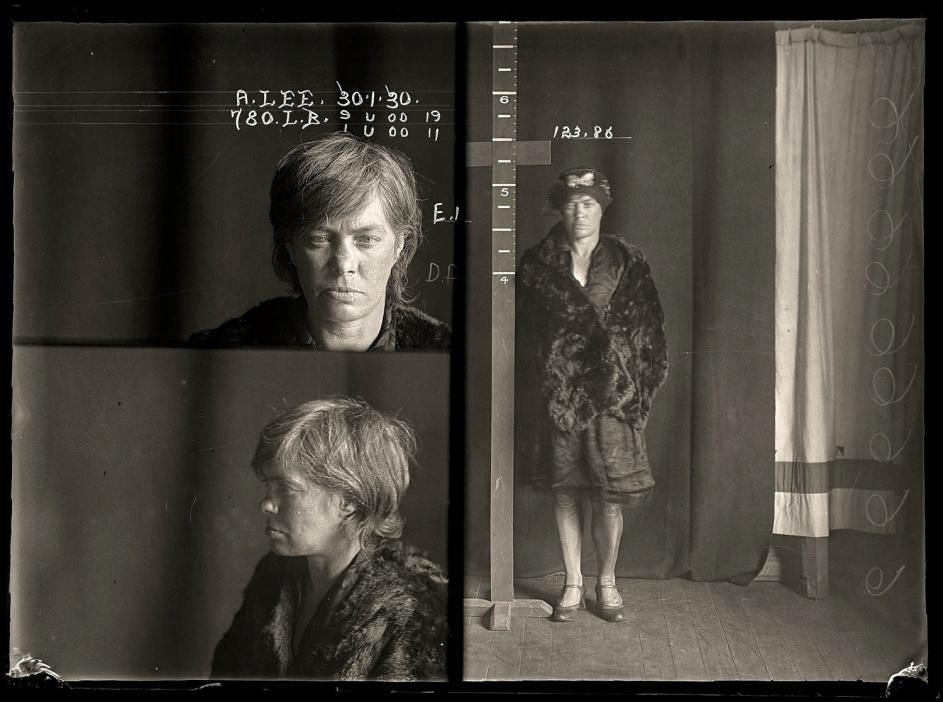

This section of the discussion features black and white still photos that were all taken between the years 1919 and 1930. The photos are mug shots taken of female convicts; they originate from the archives collected by the Australian Department of Prisons between the years 1910 and 1964. None of these women are violent offenders; most are felons charged with burglary, some with bigamy. The mug shots themselves remain of interest because they belong to a group of “Special Photographs,” taken between the years 1910 and 1930. In these photographs the Australian police department endeavoured to give the subjects of the photos freedom to appear in a non-standard way in their incarcerating documentation.

These mug shot photos originate from a “series of around 2500 special photographs taken by New South Wales Police Department photographers between 1910 and 1930. These special photographs were mostly taken in the cells at the Central Police Station, Sydney and are, as curator Peter Doyle explains, of men and women recently plucked from the street, often still animated by the dramas surrounding their apprehension” (New South Wales Police Department n.p.).

These photos depict the women with implicit judgment as to their value, based exclusively on their age and their physical attractiveness. Each photo contains an observation from the arresting officers as to the subject’s pulchritude (or lack thereof); their crimes, therefore, feature less significantly than their gender. Beyond that, some of the women themselves in some cases appear aware of the camera’s susceptibility to their gender, while others understand that whatever power they once had to sway the photographer and the arresting officers has long passed. These mug shots then become a fascinating study in how women perceive themselves through the photographic image, depending on their social value at the time. For example, the young, attractive women have a different way of looking at the camera than the elderly or unattractive women do. As Jones writes, “photographs of women’s bodies…instantiate a triple state of fetishism…the psychic fetishism of patriarchy grounded in the specificity of the corporeal body; the commodity fetishism of capitalism…and the fetishizing properties of the photograph – a commemorative trace of an absent object” (Jones 315).

Women often internalize the eye of the camera – namely, its visual assessment of them. “Through the photographic image, femininity is constructed as a locus of male desire and pleasure, embedded in the photographed and commodified female body via a system of fetishistic visual codes. The photographed female body operates as an object of exchange” (Jones 315). Women often adopt as a transactional relationship with their sexuality and with men as a result, because the “production of women, signs and commodities is always referred back to men…wives, daughters and sisters have value only in that they serve as the possibility of, and potential benefit in, relations among men…the sexuality of men is played out through the bodies of women, matter or sign” (Jones 315).

Determined largely by the male standard of the value or worthlessness of females therefore, historically speaking, as Levin and Perreault note, the “camera stands between [a] creation and an original referent. Its production is a kind of originary cause or pretext… The camera mediates; it makes the past visible, the unseen, seen; the camera protects the viewer from referent/object or person… The work [is] transforming images that have been determined in a different context at a different time – thus claiming feminist authority over images of women whose existence as image was determined by male authority, science, medicine, law, or religion” (Levin and Perreault 128).

The first photo is a 1922 mug shot of Alice Adeline Cooke; she is 24 years old in this photo (New South Wales Department of Prisons n.p.)

According to the New South Wales Department of Prisons, “by the age of 24 Alice [Adeline] Cooke had amassed an impressive number of aliases and at least two husbands. Described by police as rather good looking, [Alice Adeline] Cooke was a habitual thief and a convicted bigamist” (New South Wales Department of Prisons n.p.) In the photograph, Alice Adeline Cooke openly flirts with the photographer; she stares at the camera with a heavily provocative and lustful expression, and her magnetism infuses the photograph with a strong and unmistakable aura of sexuality. Alice Adeline Cooke’s sexuality also clearly affected the arresting officers, who felt compelled to comment that she was “rather good looking,” despite the fact that she was a thief and had already deceived at least two men (New South Wales Department of Prisons n.p.). Thus, the present reflected in this photograph speaks to the power of sexuality that women can wield in certain circumstances. Unfortunately, Alice Adeline Cooke’s open invitation did not succeed in releasing her from custody; however, this photo stands as a monument to the power of the photograph to capture and demonstrate personality and character in its subject.

The second photo is entitled “Amy Lee, Criminal Record Number 780LB, 30 January 1930.” At the time of her arrest, 41 year old Amy Lee is a middle-aged drug addict fallen on hard times, according to the New South Wales Department of Prisons. The arresting officers note that “Amy Lee was described in court as a good looking girl until she fell victim to the foul practice of snorting cocaine. Her dry, blotchy skin is testament to the evils of addiction” (New South Wales Department of Prisons n.p.).

A similar description accompanies Fig. 8, “From Drugs to Mugs: Disfiguring Toll of Addiction,” the 2004 photograph of an unidentified woman arrested for possession of methamphetamine (MSNBC n.d.). Again, the description focuses entirely on the physical appearance: “The pairs of mug shots, which graphically display the damage drugs can do to the face, were collected by the sheriff’s office in Multnomah County, Ore. Faces that were normal — even attractive — in initial photos, shot when addicts were first arrested, metamorphose over years, and sometimes just months, into gaunt, pitted, even toothless wrecks” (Carroll n.p.).

Thus, the present the viewer sees reflected in the mug shot of Amy Lee in 1930 – and the commentary her image elicits – has not changed at all. Interestingly, similar expressions exist between Amy Lee and the unidentified woman. Both women wear slightly belligerent expressions, which may be simply be related to withdrawal from drugs coupled with the unfortunate circumstances both women finds themselves in. Nonetheless, the mirror expressions create a tactile and fascinating connection across 74 years.

Since Amy Lee’s photo was part of the Special Photographs, her mug shot offers more insight into her state of mind at the time of her arrest. The photograph contains three angles: a front view, a profile and a full length view. The viewer sees in the full length view that Amy Lee was reasonably well dressed at the time of her arrest; she has a fur coat, stylish shoes and a fashionable hat. The present reflected in Amy Lee’s mug shot tells the viewer that in Amy Lee’s recent past, she possessed enough financial security to afford nice clothes; however, her gaunt, pockmarked face and empty eyes tell the viewer that her addiction has overtaken her concern for her appearance. “Amy Lee, Criminal Record Number 780LB, 30 January 1930” speaks to the power of photography to tell a story and create a history around its subject, particularly in the examples provided by the Special Photographs, which contains rich allusions to the circumstances that surround the arrests of their subjects.

According to the New South Wales Department of Prisons, “Kate Ellick had no family to support her and no fixed address. In the early 20th century employment options were limited for women of her age and there was no aged pension. Ellick was homeless when arrested in Newcastle and was sentenced under the Vagrancy Act to three months in prison” (New South Wales Department of Prisons n.p.).

At the time of her arrest Kate Ellick was 59 years old. She appears much older in her mug shot. The description makes no mention of a crime per se; rather, it appears that Kate Ellick was arrested for being old and poor. This photograph contains the poignant expression of a woman who has outlived whatever social value and tools of leverage that she may have once had, beyond whatever help or support her looks may have garnered, at a time in history when the social safety net did not yet exist. The photograph harkens back to a time when it was incredibly dangerous for women to remain unmarried. Thus, Kate Ellick’s expression is one of the simplest out of all of the Special Photographs. She wears a ghost of a smile, but due to the fact that she appears to have lost her teeth, the smile remains subdued. The smile itself also reflects genuineness; it is a decidedly pure smile, lacking in artifice, and with no manipulative agenda other than perhaps the automated response to having her photo taken, even under such circumstances as her own arrest.

Figs. 10 and 11, “Mug Shot of Emma Rolfe (also known as May Mulholland, Sybil White, Jean Harris and Eileen Mulholland),” offer fascinating into the power of photography to convey deep character traits in its subject. The New South Wales Department of Prisons describe “Mug Shot of Emma Rolfe (also known as May Mulholland, Sybil White, Jean Harris and Eileen Mulholland)” as “Special Photograph no. 126” (New South Wales Department of Prisons n.p.). The arresting officers provide a description of career criminal Emma Rolfe, “better known as May Mulholland…also as Sybil White, Jean Harris and Eileen Mulholland…, [who] had numerous convictions in the period 1919-1920 for theft of jewellery and clothing… All quality items: silk blouses, kimonos and scarves, antique bric a brac, etc.,…from various houses around Kensington and Randwick, and from city shops. She appears as a mature woman in the New South Wales Criminal Register of 5 December 1934. By that time she is well known for shoplifting valuable furs and silks from city department stores. When subjected to interrogation by Police who are not acquainted with her character, the entry notes, she strongly protests her innocence, and endeavours to repress her interviewers by stating she will seek the advice of her solicitor” (New South Wales Department of Prisons n.p.).

“Mug Shot of Emma Rolfe (also known as May Mulholland, Sybil White, Jean Harris and Eileen Mulholland)” was taken in 1920, and the description gives the viewer access to the full portrait of Emma Rolfe, the only true hardened criminal in the group of women featured in this discussion. As Doyle suggests, “compared with the subjects of prison mug shots, the subjects of the Special Photographs seem to have been allowed – perhaps invited – to position and compose themselves for the camera as they liked. Their photographic identity thus seems constructed out of a potent alchemy of inborn disposition, personal history, learned habits and idiosyncrasies, chosen personal style, [including] haircut, clothing and accessories, and physical characteristics” (New South Wales Police Department n.p.). What the present depicts in the two mug shots of Emma Rolfe is that she understood the value of the Special Photographs, and endeavoured to use the Special Photographs to her full advantage. In both photos, Emma Rolfe consciously acts for the photographer, assuming a dejected physical stance, staring down at the floor and wringing her hands. In both photos she avoids the eye of the camera and the photographer, yet in the absence of her gaze, she demonstrates an affection of innocence, fear and terrible sadness. These protestations of innocence persist despite the fact that Emma Rolfe had many experiences inside of police stations, and numerous experiences of being arrested (New South Wales Police Department n.p.). Thus, the present of the photograph depicts a women wrongfully arrested, terrified, ashamed and victimized, while the description of the character depicts a first class con artist at work in these photos, using the license given to her by the mandate of the Special Photographs to full effect (New South Wales Police Department n.p.)..

Fig. 10. & Fig. 11. “Mug shot of Emma Rolfe (also known as May Mulholland, Sybil White, Jean Harris and Eileen Mulholland)”; 1920; New South Wales Department of Prisons; Historic Houses Trust; Sydney, Australia; Web.

Discussion

The truth of time exists in its constant movement. As Benjamin explains, “the true picture of the past whizzes by. Only as a picture, which flashes its final farewell in the moment of its recognizability, is the past to be held fast” (Benjamin n.p.) The photograph therefore remains an “an irretrievable picture of the past, which threatens to disappear with every present, which does not recognize itself as meant in it” (Benjamin n.p.).

The major strength of the theoretical framing of the photographic image employed in this study is its understanding of the photograph “associated with presence over an extended time span, because the stillness of the picture renders it a prolonged object of contemplation” (Van Gelder and Westgeest 95). This theoretical framework effectively slows down time enough so that the social and political structures within the photograph – both explicit and implicit – can be determined and thoroughly analyzed. As Susan Sontag writes, the photograph stands still as an thing to comprehend, as long as the viewer wishes to comprehend it, unlike a film which must be mechanically stopped in its frame in order to be studied, or studied as a continuum (Sontag 17). As Sontag explains, “photographs may be more memorable than moving images, because they are a neat slice of time, not a flow. Television is a stream of underselected images, each of which cancels its predecessor. Each still photograph is a privileged moment, turned into a slim object that one can keep and look at again” (Sontag 17).

In the visual analysis of the preceding photographic images, this study demonstrates the way in which the power structures themselves affect subject representation, and the “presence of photography with memory…[makes] the past part of the living presence” because these power structures still exist (Van Gelder and Westgeest 95). Thus the “stopped time” quality of the photographic image functions as a catalyst for the imagined past to demonstrate its relationship with the present experience of the viewer. The recognition of this shared social, political and cultural space between subject and viewer across time is what this study explores.

Several power structures noted in the photographs from the past were rooted in the technical production of the photographic images themselves. One example of this occurs in the differences in how women and men were photographed – as evidenced by the style of photography used in the Special Photographs of Emma Rolfe and Alice Adeline Cooke (New South Wales Police Department n.p.). As Keating notes, the photographers working at this juncture of history were trained to photograph character differently in men and women. In these professionals, “discourse of character is almost invariably complicated by a discourse of gender, as many photographers start with the assumption that men and women have different degrees of character. This ideology of difference impacts their formal choices in concrete and specific ways… [yet] the ideology of difference invoked by photographers [remains] a cultural construction” (Keating 93). An example of this phenomenon occurs in this instruction, dated 1919, from portraitist Paul L. Anderson:

“Men are most likely to have strongly marked characters, since their mode of life tends to develop the mental processes and to encourage decision, whereas our present unfortunate ideals of feminine beauty incline toward mere regularity of outline and delicacy of complexion. One finds, nevertheless, a good many women whose features express mental activity and firmness of will, the higher beauties of the mind rather than the mental indolence which is imperative in the cultivation of what is popularly termed beauty” (Anderson 237).

The photographs of Emma Rolfe and Alice Adeline Cooke also attest to the oftentimes problematic relationship that women have with their own images, in that, the photograph typically levels an automatic gender stamp upon its female subjects, with an implicit valuation as to their social worth. At the time when these photos were taken gender, as Keating notes, also denoted character, regardless of the authentic character of the female subject (Keating 96). Photography differed between men and women, even those convicted of crimes, due to the prevailing belief not only that “character is more or less visible on a person’s face,” but also that “character…both as an internal state and as its external manifestation…supposedly tended…to vary with respect to men and women” (Keating 96). Anderson wrote in 1919 that “we are accustomed to associate brightness and vivacity with …portraits of women, though here the scale may be extended, more contrast being used, even…in the case of women of strong character…approaching the full-scale, powerful effects which are valuable in portraying men. Evidently, men less accustomed to commanding positions, that is, artists, writers, students and the like, approach more nearly to the feminine gentleness of character, and they, since their work is more in the realm of the imagination, are generally to be rendered with less contrast and vigour than those who have charge of large affairs” (Anderson 37).

At the time that Alice Adeline Cooke’s photo was taken, for example, she appears to have understood the power of her beauty and her image – insofar as a tool to manipulate – judging by her attempt to seduce the photographer, yet the relationship between her and her image, if she did indeed view it as a bartering tool, speaks to the larger problem of women and photographic representation (Jones 315; New South Wales Department of Prisons n.p.). The photographer who took the photos, however, could well have been influenced by the sexist social and political attitudes that dominated photography at that time, as evidenced by the following quote from an article on photography written in 1932:

When photographing women they should be done so beautifully. The lighting should be in a high key and aim to express femininity. The tonal range between the highlight and the shadow should never be very great. The lighting for men on the other hand should express rugged virility. The tonal contrast should be much longer than that employed for women. In fact it should be more or less contrasty without being violent. (Hesse 37)

In 2011, the issue of women’s relationship to their image continues to do harm to women’s self worth; the photographic image relentlessly pursues beauty in women to the exclusion of all other qualities, and beauty is still the most persuasive and effective form of power available to women. To claim power through the body, through sexuality, will only ever be fleeting however. The unbalanced attention placed on the photographic image encourages women to separate their worth from themselves and place it in the hands of an exterior referent that loses power as it ages; once youth and beauty are gone, agency and self-affirmation follow.

Similarly problematic is the power position of the photographer. This is especially true of Holocaust imagery. Barbie Zelizer’s book Remembering to Forget: Holocaust Memory through the Camera’s Eye offers an analysis of Holocaust photography with special emphasis on the eye that created the present moments rendered in the photos – overwhelmingly the “victorious” perspective of Allied photographers (Zelizer 108). Many of the most famous Holocaust photos available in 2011 centre around stacks of corpses discovered in 1945 upon the liberation of concentration camps such as Buchenwald and Auschwitz, and these “harrowing shots of corpses, skeletal victims, and mass graves” now function largely as silent victims of Nazi aggression (Kattago 102). However, as Zelizer notes, the dearth of photographs from the point of view of the victims of the Holocaust creates a one-sided, often empty experience in the viewer (Zelizer 202).

“The photos functioned not only referentially but as symbolic markers of atrocity in its broadest form,” thereby the replication and reappearance of photograph after photograph of “mass graves, of survivors looking at the camera, of confrontation shots between survivors and guards – created a stock of generalized images” that essentially numbed the viewer into a pre-programmed psychological response (Zelizer 111; Kattago 102). Faced with the endless visual parade of “a commandant, a mass burial, a common grave, a charred body, human cordwool” the specifics of time, place and person faded, and the “the exact details of the atrocities mattered less than the response of bearing witness” (Zelizer 121; Zelizer 126). Holocaust photographs therefore function largely as “symbols or cultural icons” (Zelizer 108). “In empowering both those who seek authentication of Nazi atrocities and those who deny them, atrocity photos thereby threaten to become a representation without substance” (Zelizer 201).

The disembodied nature of numerous Holocaust images that were published over and over in the media since 1945, Zelizer argues, have shaped the response of successive generations to genocide in general (Zelizer 202). Zelizer and other scholars fear that “these images and their continual recycling may have reached a saturation point. Because concentration camp photos are the first document of such mass atrocity, they have become the standard against which subsequent atrocity is measured. Thus, pictures of Cambodia, Rwanda, and Bosnia inevitably refer back to the European killing fields” (Kattago 102). Zelizer’s view is that photography often outstrips reality; “photography confuses fact and fiction, and…images take on lives of their own” (Kattago 102).

While Holocaust photographs are important reminders, Zelizer cautions that they represent essentially the perspective of the victors – the Allied photographers, who were largely biased toward documenting the carnage at the end of the war – and the Nazi soldiers, whose point of view remained that of aggressor and further shaped how the victims were experienced. In other words, the present depicted in most if not all Holocaust photos remains devoid of an essential perspective – that of the Jewish people themselves – which viewers must always remember when they consider these photographs. As Kattago notes, the Holocaust photographs of “Germany at war’s end – of civilians, returning POWS, Allied officers, and concentration camps – offer evidence of historical fact. But they also offer testimony that seeing is not only believing or a sign of truth; seeing is also subject to political and cultural trends” (Kattago 102).

The disembodied nature of most Holocaust images also “creates numerous potholes in the journey between past and present. Uncertain of where one memory ends and another begins, we blur events with the tools by which we remember them” (Zelizer 202). Holocaust images become the images emblematic of genocide itself; in other Zelizer’s words, Holocaust imagery launched humankind on a “macabre journey around the globe, depicting genocide and barbarism that have ended the lives of an estimated 50 to 170 million civilians…[including] massacres in Rwanda and nearby Burundi, [and] mass barbarism in Bosnia” and while these more recent genocides appear more localized than the Second World War, Zelizer argues that they all take their cue for representation from Holocaust imagery. The way in which the Holocaust was documented, in other words, benchmarked all other forms of ensuing documentation of ensuing conflicts and genocidal wars. Contemporary atrocities also “depend more directly than in previous eras on the media for their public representation. Much of this has to do with photography, which over the years has been instrumental in helping publics bear witness to atrocities that they did not personally see” (Zelizer 202). Arguably, once the Holocaust became newsworthy, it engendered all atrocities and genocides that followed guaranteed coverage in the media.

Conclusion

The aims and objectives of this study have been to elucidate the relationships involved in the experience of the photographic image, including the link between the emotional state of the viewer and the meaning creation that occurs upon viewing the photographic image. Though the past is a fiction, to the same extent that the photographic image is a fiction, the viewer nonetheless generates meaning within her own mind, based on her own personal and cultural reference points that she applies to the photograph at the time of viewing. Thus, photography, meaning creation and the experience of the present in the past comes full circle – it is a private ritual, a private moment of meaning construction, one that can only occur between the viewer and the photograph (Ferris 66).

Of the numerous modern influences on photography, the most transformative remains the advent of digital photography, digital image manipulation software, social networking and digital techniques. As Buse explains, “the most profound development in the production of photographic images is the shift from chemistry to electronics…one of the most salient features of the digital image is the speed of its production and potential transmission, a feature that had been anticipated almost half a century earlier by the Polaroid-Land process. The advent of the digital…has repercussions through all strata of culture, and it correspondingly agitates the analysts of culture” (Buse 31) Digital photographs have a “throw-away quality” that earlier forms of photography do not (Buse 34).

Digital photographs also remains largely stored in electronic devices such as phones and laptop hard drives, thus the tangible element to the photographic image has also changed irrevocably. What has not changed is the “desire of contemporary masses to bring things closer spatially and humanly, which is just as ardent as their bent toward overcoming the uniqueness of every reality by accepting its reproduction” (Benjamin n.p.). One could categorize a Facebook page as “an extraordinary apparatus to enable individuals to image, archive, digitalize, objectify, and take ownership of the passing moment” (Clark 177). As Buse observes, the “intimacy promised by this technology and by instant imaging in general suggests that magical thinking in the stronger sense is by no means incompatible with a wider consumer capitalism” (Buse 44)

The most important technological changes wrought by digitising in regard to the photographic image is the loss of the referent; the question of whether or not the referent actually exists in the digital age of photography and Photoshop gives rise to considerable debate amongst visual culture scholars. In Practices of Looking, Marita Sturken and Lisa Cartwright assert that the invention and adoption of new digital imaging technologies, have produced a “fundamental transformation in the nature of images” (Furstenau 118). Photographic images can now be a composite of any number of referents, all digitally enhanced and manipulated, and originating in multiple cultures and historical epochs simultaneously. As Sturken and Cartwright explain, “in the 1980s and 1990s, the development of digital images began to radically transform the meaning of images in Western culture…[since unlike digital images] analogue images bear a physical correspondence with their material referents” (Sturken and Cartwright 138). The traditional analogue photograph, Sturken and Cartwright argue, was produced “according to strict mechanical and chemical processes, and which, as a result, bore a unique relation to the objects it represented” (Sturken and Cartwright 138). Sturken and Cartwright view analogue images as “indexical, [having achieved] a semiotic status that had determined a specific epistemological attitude” (Sturken and Cartwright 138)

The difference between digital photographs and analogue photographs, according to Sturken and Cartwright 138, “is thus derived from the belief that [the analogue] has a referent in the real” (Sturken and Cartwright 140). The scholars distinguish between the “cultural meaning” of photographs, which they believe “is derived in large part from their indexical meaning as a trace of the real” (Sturken and Cartwright 140).

Digital technologies and image manipulating software, conversely, creates the ability to produce images that may resemble photographs, but which “don’t carry the traditional epistemological guarantee” (Furstenau 118). In the basic semiotic sense then, according to Sturken and Cartwright “this means that the photographic image is produced without a referent, or a real-life component, in the real” (Sturken and Cartwright 139). Essentially, the critics argue, “the digital and virtual image gains its value from its accessibility, malleability, and information status…the value of a digital image is derived in part by its role as information, and its capacity to be easily accessed, manipulated, stored on a computer or a web site, downloaded, etc. The idea of an image being unique makes no sense with digital images” (Sturken and Cartwright 139). In Sturken and Cartwright’s analysis, photographs created before the advent of digital technology – the so-called “mechanically reproduced image” – were disseminated within a comparable context of endless production, reproduction and recycling; the mechanically produced image therefore “gains its value through its reproducibility, potential distribution, and role in the mass media. It can disseminate ideas, persuade viewers, and circulate political ideas” (Sturken and Cartwright 139).

The idea of authenticity of the referent has been debated since Benjamin’s time. As Benjamin writes, the “presence of the original is the prerequisite to the concept of authenticity…The whole sphere of authenticity is outside technical – and, of course, not only technical – reproducibility. Confronted with its manual reproduction, which was usually branded as a forgery, the original preserved all its authority; not so vis-à-vis technical reproduction…process reproduction is more independent of the original than manual reproduction. In photography, process reproduction can bring out those aspects of the original that are unattainable to the naked eye yet accessible to the lens, which is adjustable and chooses its angle at will.