Introduction

Aviation plays a pivotal role in the contemporary world, providing rapid transportation and allowing for extremely swift travel. This mode of transportation is also the safest transport available today (Duguay 2014), which is, in part, due to the strict physical security measures implemented in airports.

However, the multi-layered security system – the dominant approach to airport security – is nowadays being criticised as consuming an excessive amount of money and resources; an alternative has been proposed in the form of a risk-based, outcomes-focused approach to aviation security, which may possibly save resources while lowering the level of security by a negligible amount.

The current paper discusses key points of these two approaches to physical airport security, provides a comparison, and then engages in critical evaluation to identify their benefits and drawbacks. It is concluded that the implementation of the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach to physical security in aviation might be a viable alternative to the multi-layered security system.

The Layered System of Aviation Security

Currently in civil aviation, a considerable proportion of airports use the so-called layered physical security system for the purpose of safeguarding themselves from potential terrorist attacks (Chatterjee, Hora & Rosoff 2015). This system is comprised of a number of ‘layers’, that is, different security measures aimed at denying unauthorised individuals access to facilities, as well as intended to protect passengers, airport staff and property from damage or harm that could result from a terrorist attack, theft, espionage or any other activities that might be carried out with malicious intent (Chatterjee, Hora & Rosoff 2015).

The crux of the layered system of security is that it should permit the detection of suspicious individuals, objects, cargo and more by conducting a wide array of scans and checks so that in the event any of these checks should be unable to detect anything suspicious, other checks will be able to do so, thus compensating for any potential weaknesses of the rest of the ‘layers’ (Jackson & LaTourrette 2015).

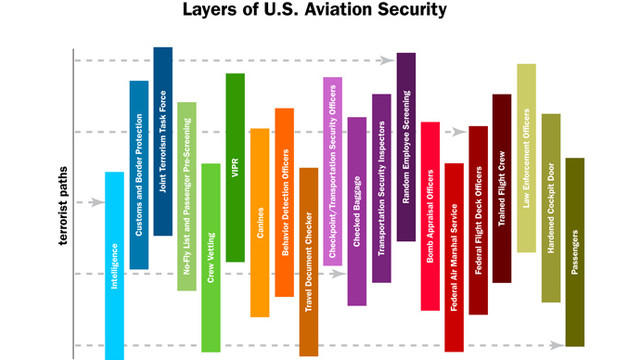

A large number of layers are simultaneously employed. For instance, in the United States, the Transportation Security Administration (2017) stipulates that 20 different layers of aviation security are to be in place in civil airports. These 20 layers of security are as follows (Transportation Security Administration 2017):

- Intelligence: the process of collecting and analysing data about phenomena taking place in airports is accomplished by intelligence officers who also make an effort to determine the currently existing threats and issues in the aviation industry (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Customs and border protection: customs officers direct their efforts towards securing trade and passengers travelling through the immigration departments in order to detect weapons and potential terrorists possibly presenting a danger to aircraft, personnel, passengers or airport facilities (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Joint terrorism task force: this force is based on the efforts of local agencies and residents to enhance airport security in the region and ensure its adherence to safety regulations. This task force may include such entities as the FBI, customs officers and others (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- No-fly lists and pre-screening of passengers: these no-fly lists contain the names of individuals who are considered dangerous and are consequently prohibited from making use of civil aircraft as a means of transportation. Passengers are pre-screened to detect any potential threats to aviation safety (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Crew vetting: the members of aircraft crews, along with airport employees, are thoroughly screened and vetted; their personal details such as date of birth, country of residence, and licence numbers are collected in order to ensure that these individuals meet all necessary requirements and do not themselves pose a threat to security (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- VIPR (visible intermodal prevention and response): these teams of officers collaborate with security departments in an effort to enhance the chances of detecting potential hazards (such as biological, radioactive, chemical etc. threats) related to passengers (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Canine: numerous security teams use dogs with the purpose of better detecting explosives and other dangerous or illegal objects (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Behaviour detection: specifically designated officers are trained to detect individuals who may display suspicious behaviours (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Travel documents checking: the clients of aviation service suppliers must provide their identification documents and tickets to security personnel in order to confirm their identity. Otherwise, additional checking procedures will be carried out (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Checkpoint and transportation security officers: checkpoint counters are utilised at the terminal to prevent passengers from carrying banned items onto a plane (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Checking passenger luggage: all passenger luggage to be stored in the cargo compartment of an aircraft is subjected to X-ray screening, as well as to screening aimed at detecting traces of explosive substances (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Transportation security inspectors: these individuals play the role of safeguards protecting airports and cargo areas from a broad range of types of threats (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Random screening of employees: Any persons provided with access to airport facilities are subjected to random checking procedures; these operations might even take place on a daily basis (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Transportation security specialists in explosives: the efforts of these professionals are aimed at carrying out a process that supplies an advanced level of security, as well as training other officers and inspectors present in the airport in order to improve their skills pertaining to the detection of explosives (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Federal air marshal service: these specialists are similar to Visible Intermodal Prevention and Response professionals; however, the former usually carry firearms on their persons and possess specific training aimed at facilitating their work on planes (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Federal flight deck officers: a wide array of the officers who take part in the process of flying a plane also have training that permits them to deal with various threats, should the latter emerge during flight, in an airport or at other stages of the air transportation process (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Trained flight crew: the members of the cabin crew in an aircraft are also provided training that allows them to take action with the purpose of protecting themselves and their plane in case of emergency (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Law enforcement officers: another word for police officers; these people carry weapons and are permitted to use them, as well as to use suppressive force in order to detain or neutralise malefactors who take steps aimed at disrupting the state of security in airports or on aircraft (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Hardened cockpit door: all planes are required to feature a hardened door leading to the cockpit, which is intended to make it more difficult for terrorists or other malefactors to take over the controls of a plane (Transportation Security Administration 2017).

- Passengers: the passengers may also play the role of individuals who provide safety at airports as passengers may frequently adopt a proactive approach to ensure that the aircraft and airport they are accessing are safe for their own travels, as well as for the successful aerial transportation of other persons (Kirschenbaum 2013; Transportation Security Administration 2017).

On the whole, the 20 layers of aviation security proposed by the United States Transportation Security Administration (2017) can be displayed on a diagram, as shown in Figure 1 below.

Together, these layers cover the majority of avenues for an attack. In addition, the whole compensates for the weaknesses of the separate layers; thus, they are instrumental in protecting the safety of the aviation industry and securing its passengers and facilities from possible threats such as a terrorist attack (Jackson & LaTourrette 2015).

The Risk-Based, Outcomes-Focused Approach

The risk-based, outcomes-focused approach to physical security in aviation is an alternative array of models that can be employed to provide safety in aircraft and airports (Wong & Brooks 2015). In contrast to the multi-layered approach to aviation security, which has been utilised in numerous airports around the world and is designed to be, to a certain degree, a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach, the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach has not been used so widely, and the organisations implementing it often use methods that are customised for a particular airport (Blair 2016; Duguay 2014). As a consequence, it is considerably more difficult to provide a general description of this approach due to the fact that the methods implemented in each of the airports that have adopted this approach will vary (Price & Forrest 2016).

However, it should be pointed out that this approach, rather than simply using the ‘one-size-fits-all’ regulations provided by some bodies such as national or international aviation safety agencies, implements additional measures aimed at detecting issues that may offer potential threats in a given airport, while possibly not employing all the steps recommended by the above-mentioned authorities because such steps may be of low or negligible effectiveness while being costly and resource-consuming (Wong & Brooks 2015).

Therefore, generally speaking, air travel companies that use the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach will attempt to assess the effectiveness of particular steps aimed at the provision of security in these airports (Sewell, Lee & Jacobson 2013) and, based on that assessment, will make a decision about which of these methods to preserve and which of them to discontinue.

In addition, airports may also utilise other methods, such as additional screening of ‘suspicious’, potentially high-risk passengers, with the purpose of more effectually detecting any potential threats to the security of the airport’s facilities and its aircraft, if these particular methods are deemed viable for the given airport (Blair 2016; Woods 2017).

An example of an airport that uses the risk-based approach to aviation security is the Ben Gurion International Airport in Israel; see Figure 2 below (Blair 2016). Ben Gurion is the only international airport in Israel, and this fact highlights the facility’s vital importance for the country. Should it be subjected to a terrorist attack, the whole country might be faced with an international blockade for a certain amount of time, leading to heavy losses (Blair 2016). Consequently, the security measures that are implemented in that facility are relatively heavy.

On the whole, in addition to employing its own multi-layered system of security measures, the airport uses individual assessment as another measure with the purpose of identifying potentially dangerous passengers (Blair 2016). For instance, some persons, such as those who are identified as Arab Muslims, may be required to go through an additional, lengthy process involving a security check so as to ensure that they do not pose a danger to the airport facilities, aircraft, staff and passengers (Blair 2016). At the same time, the airport does not implement a number of layers of security that would be ineffective in that facility; only about 12 layers out of the entire set are used in the airport (Blair 2016).

The implementation of these additional security measures has permitted the Ben Gurion airport to be exceptionally safe; in fact, no one has been killed or injured inside the facilities of that airport or on aircraft departing from it for more than 45 years (Blair 2016). Nevertheless, security checks in this airport, on average, consume a considerably greater amount of time than might be found in most European airports.

This fact remains tolerable because Ben Gurion is a relatively small airport; for example, in 2015, it served only about 16.5 million passengers; in contrast, approximately 75 million customers were provided with air transportation services in Heathrow Airport in England over the same period (Blair 2016). Thus, it is clear that the utilisation of a model that is similar to the aviation security approach of Ben Gurion is impossible for major European airports due to the volume of passengers that these European airports are required to serve (Blair 2016).

Contrast and Comparison

Having identified the essentials of both security models, it is possible to make a comparison of these models. When comparing these approaches, it is possible to observe that both use multiple layers of security that have been proposed or approved by some national or international organisations for aviation security (Price & Forrest 2016).

In contrast, whereas the multi-layered approach involves the utilisation of all possible layers of security, the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach may opt to refrain from putting in place some layers of security that are not deemed to be viable, in certain cases replacing them with other security measures or other types of screening or, in other cases, even simply omitting them without any replacement.

Another difference between the two approaches to aviation security pertain to the applicability of the particular measures that are implemented within these models. More specifically, the multi-layered approach to security in the aviation industry was created with the purpose of serving as a ‘one-size-fits-all’ method so that it could be implemented in a wide array of airports without taking into account the whole range of factors existing in each of these particular airports (Cole 2014).

On the other hand, the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach does the opposite; while it usually still employs a considerable proportion of the layers as provided by the other model, the risk-based, outcomes-focused method makes an attempt to assess the effectiveness, efficiency and viability of particular layers or measures that exist within the recommended set of layers designed for protection in order to determine which of these measures should continue to be implemented in a given airport, those which should be dropped and those which should receive additional support because of their increased efficaciousness and applicability within that facility (Stewart & Mueller 2013).

Therefore, the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach does not serve as a ‘one-size-fits-all’ method, instead requiring that adjustments must be made for each particular airport. Clearly, such adjustments ought to be made based on thorough research and analysis of relevant data in order to ensure the maximum viable level of safety for the passengers, personnel and facilities of the airport in question (Duguay 2014).

As has been observed, the use of the multi-layered approach to aviation security is determined in light of the regulations developed by various national and international authorities; these authorities provide instructions about which steps to take in order to provide the required levels of security, including when and how to take these steps (Price & Forrest 2016).

On the other hand, in the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach to aviation security, any decision about implementing this or that layer or measure of security is to be made by local organisations, including the airports themselves, based on an analysis of relevant data. Therefore, an important distinction is that whereas in the multi-layered approach, all the instructions are made in the ‘centre’, in the risk-based, outcomes-focused model, the decisions are made in particular places (Duguay 2014).

Critical Evaluation of the Two Approaches

The Multi-Layered Approach

Generally speaking, it is possible to provide a critical evaluation of the multi-layered approach to aviation security in the light of several aspects of its functioning. For example, it should be observed that the purpose of the implementation of this approach in an air transport organisation is to cover and safeguard all possible avenues through which an attack on an airport can be carried out (Duguay 2014). As one of the consequences of covering all these avenues, the security in airports utilising this model should be relatively high.

On the other hand, it should be observed that the coverage of a variety of potential avenues of attack is determined by the possibility of attacks through these avenues, rather than by an adequate estimation of the probability of such attacks occurring (Duguay 2014). On the whole, Duguay (2014) states that the perceptions of risks rather than accurate estimates of these risks guide the creation of numerous aviation security standards. As a result, even those avenues through which an attack is extremely unlikely will be covered, which not only leads to additional cost but also involves additional inconveniences to the passengers and a lowered passenger throughput in an airport (Duguay 2014).

Therefore, it is apparent that a wide array of the activities carried out in the aviation sphere that is using the multi-layered approach to security are often ineffective. In this case, their implementation can be optimised, for instance, by rearranging the resources spent to uphold these activities so as to reduce their cost while preserving their effectiveness (Stewart & Mueller 2013). Clearly, if this is so, it means that on the whole, the multi-layered approach to aviation security features a major fault: namely, ineffectiveness and low efficiency.

It is clear that the excessive cost of the multi-layered approach to aviation security is also of paramount importance from a variety of perspectives. Not only does it reduce the profitability of aviation services, it also means that the money and resources spent on ineffective security measures may as well have been wasted.

According to Duguay (2014), a million dollars per year spent on fighting malaria could potentially result in saving the lives of a thousand children, whereas billions of dollars spent in the United States are dedicated to protecting civil aviation. Therefore, it is apparent that if any money that is used in aviation security can be saved, and the risks resulting from such saving are negligible, an effort to economise this money ought to be made (Bagchi & Paul 2014) so that it would be possible to redirect the funds so conserved to save lives elsewhere.

The Risk-Based, Outcomes-Focused Approach

In contrast to the multi-layered method, the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach to aviation security is, in fact, aimed at identifying those avenues of attacks that are the most probable and covering them to address the risk of attack, minimising this risk as a result (Stewart & Mueller 2013). Consequently, those avenues through which an attack is unlikely will be less covered by security measures, which as a result makes them vulnerable for a possible attack. Therefore, while using the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach, it is pivotal to continuously assess and re-assess the potential probabilities of risks as a way to be able to address such risks if they emerge.

Thus, as Duguay (2014) puts it, in the multi-layered approach, the measures for ensuring aviation security are guided by possibilities, whereas in the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach, they are guided by probabilities. In other words, in the multi-layered method, governmental agencies may often introduce new regulations (for example, after an attack has happened) and never cancel them thereafter, so the additional spending, even though it may possibly be wasteful, will be effectively permanent (Duguay 2014). In addition, the perception that safety measures should be further increased is often strengthened by the heavy security that is already present (Duguay 2014).

On the other hand, in the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach, measures that are aimed at ensuring the security of an airport could be implemented based on the actual estimated probabilities of an attack or some other type of security breach (Stewart & Mueller 2017).

In fact, these probabilities ought to be based on relevant data that has been collected in airports and thoroughly analysed (Stewart & Mueller 2017). Although it has been observed that it is difficult to collect statistical data for the purpose of assessing the probability of attacks due to the fact that such attacks are extremely rare, the data about outliers can still be employed for this purpose; according to other opinions, it is better to focus on airport resiliency rather than attempting to predict an adverse event from virtually no data (Duguay 2014).

In addition, it is important to observe that the implementation of the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach is likely to be less costly as a result of the fact that this approach should be based on the probability estimates of a risk and, therefore, ought to allow for savings in terms of costs that would previously have been spent on covering unlikely avenues of attack (Gillen & Morrison 2015). As previously noted, this might allow for economising and releasing significant funds and resources, which can then be employed in ways that can save lives elsewhere, rather than wasting them on ineffective aviation security measures in an airport that already represents the safest means of transportation in the world (Duguay 2014).

It is also paramount to stress that, in contrast to the multi-layered approach to aviation security, by its nature a ‘one-size-fits-all’ approach, the risk-based, outcomes-focused method is meant to be adjusted to the peculiarities of a particular airport or facility (Stewart & Mueller 2013). This is due to the fact that the risky avenues of attack to be covered are calculated for each airport separately, and the prevention measures for each airport are driven, in particular, by data obtained in that specific airport. This should allow for yet more efficacious coverage of weaknesses, along with more effectual addressing of potential threats to aviation security in a particular airport (Cavusoglu, Kwark, Mai & Raghunathan 2013).

Finally, it is possible to point out that the avenues of attacks are often difficult to predict due to their low frequency as civil air transport is already known to be the safest means of transportation available, and attacks on it are extremely rare (Duguay 2014). In these cases, the money that would otherwise be earmarked for security can be used in a different manner, namely, with the purpose of increasing the resilience of airports. In this situation, in the case of an actual attack that was not detected, the potential harm of such an attack would be minimised (Duguay 2014).

Conclusion

On the whole, it should be stressed that the multi-layered approach to physical security in aviation employs numerous layers of prevention measures aimed at detecting threats to aviation security; these layers are usually prescribed by state or international civil aviation agencies and are created in a manner that should permit them to be used in the majority of airports.

On the other hand, the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach also employs multiple (but rarely all) layers of aviation security while adjusting the measures taken to the peculiarities of a specific airport; this needs to be done on the basis of data that has been collected, in particular, in that airport, so as to be able to make an appropriate adjustment while taking into account the specific features of the setting.

Generally speaking, the multi-layered approach is currently the one predominantly used by airports, but it seems that the implementation of the risk-based, outcomes-focused approach might allow for saving vast quantities of money and resources, which could then be used to save lives in other areas. This can be done by getting rid of security measures that are not effective in a particular airport or that protect an avenue of attack that is unlikely to be targeted.

Given that air transport is already the safest transportation system in the world, it is pivotal to adjust security measures so that they can be focused on probabilities of attack, rather than possibilities, so that they can be aimed at improving the resiliency of airports and air transport (Duguay 2014). This might allow the saving of considerable funds and resources while sustaining only negligible decreases in the level of security in airports.

Reference List

Bagchi, A & Paul, JA 2014, ‘Optimal allocation of resources in airport security: profiling vs. screening’, Operations Research, vol. 62, no. 2, pp. 219-233.

Blair, D 2016,Israel’s risk-based approach to airport security ‘impossible’ for European airports. Web.

Cavusoglu, H, Kwark, Y, Mai, B & Raghunathan, S 2013, ‘Passenger profiling and screening for aviation security in the presence of strategic attackers’, Decision Analysis, vol. 10, no. 1, pp. 63-81.

Chatterjee, S, Hora, SC & Rosoff, H 2015, ‘Portfolio analysis of layered security measures’, Risk Analysis, vol. 35, no. 3, pp. 459-475.

Cole, M 2014, ‘Towards proactive airport security management: supporting decision making through systematic threat scenario assessment’, Journal of Air Transport Management, vol. 35, pp. 12-18.

Duguay, Y 2014, Risk based security: what is acceptable or tolerable?. Web.

Gillen, D & Morrison, WG 2015, ‘Aviation security: costing, pricing, finance and performance’, Journal of Air Transport Management, vol. 48, pp. 1-12.

Jackson, BA, & LaTourrette, T 2015, ‘Assessing the effectiveness of layered security for protecting the aviation system against adaptive adversaries’, Journal of Air Transport Management, vol. 48, pp. 26-33.

Kirschenbaum, AA 2013, ‘The cost of airport security: the passenger dilemma’, Journal of Air Transport Management, vol. 30, pp. 39-45.

Kohl, G 2012, Rethinking the layered security approach. Web.

Price, J & Forrest, J 2016, Practical aviation security: predicting and preventing future threats, 3rd edn, Elsevier, Cambridge, MA.

Sewell, EC, Lee, AJ & Jacobson, SH 2013, ‘Optimal allocation of aviation security screening devices’, Journal of Transportation Security, vol. 6, no. 2, pp. 103-116.

Stewart, MG, & Mueller, J 2013 ‘Terrorism risks and cost‐benefit analysis of aviation security ‘, Risk Analysis, vol. 33, no. 5, pp. 893-908.

Stewart, MG & Mueller, J 2017, Are we safe enough? Measuring and assessing aviation security, Elsevier, Cambridge, MA.

Transportation Security Administration 2017, Inside look: TSA layers of security. Web.

Wong, S & Brooks, N 2015, ‘Evolving risk-based security: a review of current issues and emerging trends impacting security screening in the aviation industry’, Journal of Air Transport Management, vol. 48, pp. 60-64.

Woods, S 2017, ‘Terrorism in aviation: going on holiday? Young travellers take longer to pass through security’, International Journal of Safety and Security in Tourism/Hospitality, vol. 1, no. 16, pp. 1-22.