Introduction

Care planning is a legal process that ensures the continuity of care (Chinn & Kramer 2008). According to Aggleton and Chalmers (2010), care planning portrays the care delivery pathway in a systematic and logical manner. This method facilitates collaboration among health professionals, patients and families during the decision-making processes (Ratheet et al. 2015). Patients assume an active role in the development of care plans based on the subjective identification of needs and preferences (Watson 2010). As such, personalised care is essential to meet the distinctive requirements of each patient.

The stages of the Care Planning Process

The process of developing a care plan follows a definitive cycle of four components: assessment, care planning, implementation and evaluation (Dwamena et al. 2012). According to Ratheet et al. (2015), each of the four steps mandates the health and social care professionals to provide holistic care. Although each stage requires the application of different skills, none of them supersedes the other (Fullbrook 2007). Dwamena et al. (2012) have argued that the four components provide unique contributions to the care planning procedure. According to Chinn and Kramer (2008), the failure to address the requirements of each phase undermines the quality of care.

The care planning process begins with the assessment of the client’s needs and preferences (Brotherton & Parker 2013). The use of various assessment tools is essential to generate an in-depth analysis of the care needs (McCormarck & McCance 2010). Efficient communication within the multidisciplinary team is of the essence during the assessment process. Ratheet et al. (2015) have also highlighted the significance of communicating adequately with the patients and their relations. The sources of information include non-verbal observations, written records and verbal communication (Dwamena et al. 2012).

The second phase entails setting short and long-term goals based on the findings from the initial evaluation (Aggleton & Chalmers 2010). McCormarck and McCance (2010) have indicated that practitioners should collaborate appropriately to formulate feasible goals. For example, a caregiver cannot design a care plan for a diabetic patient before conducting a rigorous assessment of needs (Brotherton & Parker 2013). In addition, the monitoring of vital signs requires the continuous collection of accurate baseline data. This information helps the health care provider to determine deteriorations in a timely manner (Chinn & Kramer 2008).

The third stage of the process entails the implementation of the interventions. This phase involves monitoring the patient’s progress to ascertain if the selected therapies are effectual (Dwamena et al. 2012). The assessment of needs is a critical aspect in each of the four stages. The appraisal of these phases provides feedback about the performance of the interventions (Brotherton & Parker 2013). Evaluation constitutes the final step of this procedure, and it determines whether the decisions taken during assessment, planning and implementation were practical (Aggleton & Chalmers 2010).

Nursing Care Models and Approaches

Patient-centred care (PCC) assumes a holistic approach, which views individuals as composed of the body, spirit and soul (Watson 2010). As such, PCC moves beyond meeting the patient’s immediate needs to addressing their social, spiritual, emotional and psychological needs (Watson 2008). The application of PCC in mental health care requires health professionals to value and respect individuals regardless of their limitations (Brotherton & Parker 2013). PCC also incorporates the patients’ family members and friends in the care planning process (Aggleton & Chalmers 2010).

Although PCC is crucial in the development of the care plan, a myriad of challenges undermines its implementation and promotion. First, it is difficult to implement the PCC in the absence of family members or advocates. This situation is particularly problematic when the client does not have a family (Dwamena et al. 2012). In addition, PCC emphasises the issue of quality but fails to provide evidence-based guidelines to realize this objective (Chinn & Kramer 2008). McCormack and McCance (2010) have indicated that the lack of conclusive evidence regarding the PCC philosophy is hindering the implementation of this model.

Secondly, the participation of patients and their families in the care planning process can be either non-existent or limited (Brotherton & Parker 2013). Aggleton and Chalmers (2010) have noted that the inferior position of family members or patients in care planning prevents them from participating actively in the care planning process. Other health and social care providers may perceive a debilitating condition as preclusion to meaningful participation (Dwamena et al 2012). On the other hand, Ratheet et al. (2015) have found out that most people are not aware of the need to take part in the care planning processes.

The Orem’s self-care model of nursing supports patient-centred care because it considers the biological, social and psychological needs of a patient during the treatment process (Simmons 2009). The Orem’s approach is similar to the Watson’s theory of caring, which mandates health professionals to provide holistic care (Watson 2010). The difference between these approaches is that the Watson’s perceptive focuses on therapeutic relationships between patients and their caregivers (Watson 2008).

By contrast, the Orem’s model mandates nurses to assist patients to meet their self-care needs (Simmons 2009). On the other hand, care providers use the Roper-Logan-Tierney model to assess the effect of an illness or hospital admission on a patient’s life. The primary goal of the Roper-Logan-Tierney model is to enable an individual to gain maximum independence (Aggleton & Chalmers 2010).

Legislation and Social Policy

The provision of patient-centred care brings to the fore ethical and legal implications. One of the principal issues in the care planning process is the concept of informed consent (Dimond 2007). The point of argument is that patients with severe mental disorders cannot take part in the development of care plans (Probst 2009). For instance, most patients suffering from dementia or other mental limitations lack the cognitive capacity to provide the consent (Kilbourne et al. 2008). On the contrary, case managers, caregivers or family members make unilateral decisions on the behalf of these individuals (Probst 2009).

Despite the previous challenges, every individual has the right to make autonomous decisions. The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) contains provisions that protect people with mental limitations (Alonzi, Shear & Bateman 2009). The Mental Capacity Act (MCA) allows patients to make specific decisions even if they suffer from dementia, stroke, brain injury, learning disabilities and any other debilitating conditions (Bisson et al. 2009). According to Boyle (2008), it is essential to conduct a mental capacity assessment before judging the ability of these individuals to make independent decisions.

Patients with mental limitations may require third parties to provide informed consent (Dimond 2007). The Mental Capacity Act allows people to appoint the people who will act as their representatives when they become incapacitated in the future (Donnelly 2009). On the other hand, MCA necessitates the appointment of independent advocates with no affiliation with the NHS or social services (Bisson et al. 2009). The Human Rights Act is another UK legislation that requires health and social care workers to provide treatment while at the same time protecting the patients’ human rights (Alonzi, Sheard & Bateman 2009).

The persisting inequalities in the health and social care services are undermining the delivery of patient-centred care (Hoffman 2011). The main problem is that people from ethnic and racial minority groups do not receive optimal care because of language barriers and cultural differences (Saha, Beach & Cooper 2008). The Equality Act has mandated the NHS to reduce inequalities and eliminate discrimination by providing culturally sensitive care. The Equality Act supports these efforts by protecting individuals against discrimination because of their age, sex, race, disability or gender and other attributes (Bisson et al. 2009).

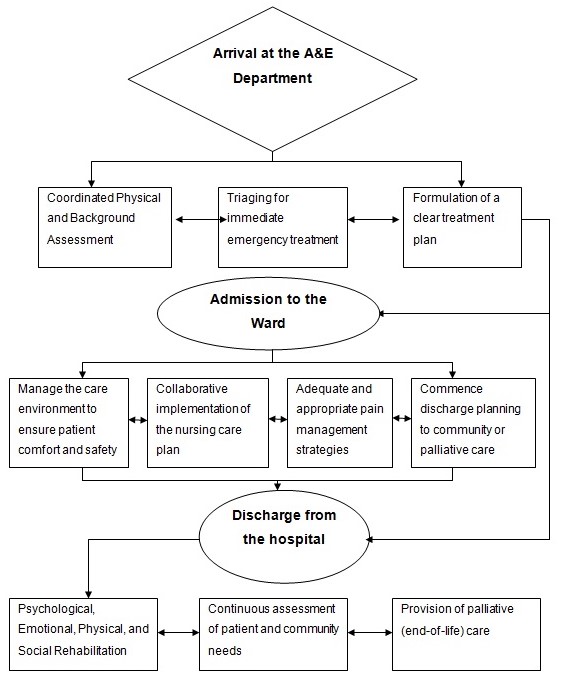

Care Planning and Dementia Flow Chart

The care pathway for patients with dementia begins when the patient arrives at the emergency department. The first step entails assessing the needs of the patient by communicating with them and their caregivers (Probst 2009). Probst has argued that all patients should have an equal access to the assessment procedure. The staff should use translation and interpreting services when handling patients from diverse cultures.

The knowledge about the Mental Health Act, the Mental Capacity Act and the human Rights Act is vital to facilitate decision-making processes. The involvement of other professionals is also essential during the assessment process to produce conclusive results (Mughal 2014).

The assessment process continues after the admission of the patient to the ward. The purpose of these activities is to prevent the exacerbation of symptoms. According to Dwamena et al. (2012), effective communication and collaboration with other professionals, caregivers, family members and friends improve clinical outcomes.

The development of the nursing plan during admission should emphasize patient comfort and safety (Ratheet et al. 2015). The most critical issues to consider include nutrition, physical activity and personal hygiene (Kilbourne et al., 2008). Communication and feedback are also fundamental aspects that professionals should incorporate into the assessment of needs and interventions (Probst 2009).

The final step of the care pathway involves the development of a discharge plan. This plan should include the patient’s preferences and needs, as well as procure community-based services (Bisson et al. 2009). The practitioner should also assess the emotional, psychological or social needs to facilitate the rehabilitation process. The evaluation of these needs helps the health and social care providers to refer the patient to appropriate services within the community. Community-based care facilitates the delivery of referral care, evaluation and assessment (Chinn & Kramer 2008).

Another crucial component of the discharge plan involves the formulation of strategies that will support the patient to live independently (Kilbourne et al. 2008). The majority of people suffering from dementia and other mental disorders often live in communities (Bisson et al. 2009). Probst (2009) has indicated that the multidisciplinary team provides support to patients and their caregivers.

Collaboration is particularly crucial since the Community Care Act requires the provision of mental and physical health services within the community (Boyle 2008). These services include social work and nursing interventions, supported accommodation, day centres and home care (Donnelly 2009). The goal of these strategies is to empower caregivers and families members (Bisson et al. 2009).

Conclusion

Care planning has increasingly become an integral component in the delivery of health and social care. The care planning process entails four aspects: assessment, planning, implementation and evaluation. One of the fundamental issues in care planning is the patient-centred care (PCC). The essence of PCC is to involve patients, as well as their caregivers and families in the decision-making processes.

Another aspect of PCC is the inclusion of the multidisciplinary team in the care process. The combination of these factors is essential in dementia care because of the debilitating symptoms of this condition. Thus, the development of patient-centred care will continue to assume a forefront position in health and social care.

References

Aggleton, P & Chalmers, H 2010, Nursing models and nursing practice, Macmillan: New York.

Alonzi, A, Sheard, J & Bateman, M 2009, ‘Assessing staff needs for guidance on the Mental Capacity Act 2005’, Nursing Times, vol. 105, pp. 24-27.

Bisson, JI, Hampton, V, Rosser, A & Holm, S 2009, ‘Developing a care pathway for advance decisions and powers of attorney: qualitative study’, British Journal of Psychiatry, vol. 194, pp. 55-61.

Boyle, G 2008, ‘The Mental Capacity Act 2005: promoting the citizenship of people with dementia’? Health and Social Care in the Community, vol. 16, no. 5, pp. 529-537.

Brotherton G & Parker S 2013, Your foundation in health and social care, 2nd edn, Sage: London.

Chinn, P & Kramer, M 2008, Integrated theory and knowledge development in nursing, Mosby-Elsevier: St. Louis.

Dimond, B 2007, ‘Mental capacity and decision-making: defining capacity’, British Journal of Nursing, vol. 16, no. 18, pp. 1138-1139.

Donnelly, M 2009, ‘Best interests, patient participation and the Mental Capacity Act 2005’, Medical Law Review, vol. 17, pp. 1-29.

Dwamena, F, Holmes-Rovner, M, Gaulden, CM, Jorgenson, S, Sadigh, G, Sikorskii, A, Lewin, S, Smith, RC, Coffey, J & Olumu, A 2012, ‘Interventions for providers to promote a patient-centred approach in clinical consultations’, Cochrane Database System Review, vol. 12, no, 12, CD003267.

Fullbrook, S 2007, ‘Best interests, a holistic approach: part 2(b)’, British Journal of Nursing, vol. 16, no. 12, pp. 746-747.

Hoffman, NA 2011, ‘The requirements for culturally and linguistically appropriate services in health care’, Journal of Nursing Law, vol. 14, no. 2, pp. 49-57.

Kilbourne, A M, Post, EP, Nossek, A, Drill, L, Cooley, S & Bauer, MS 2008, ‘Improving medical and psychiatric outcomes among individuals with bipolar disorder: a randomized controlled trial’, Psychiatric Services, vol. 59, no. 7, pp. 760–768.

McCormack, B & McCance, T 2010, Person-centred nursing: theory, models and methods, Blackwell Publishing: Oxford, UK.

Mughal AF 2014, ‘Understanding and using the Mental Capacity Act’, Nursing Times, vol. 110, no. 21, pp. 16-18.

Probst, B 2009, ‘Contextual meanings of the strengths perspective for social work practice in mental health’, Families in Society, vol. 90, no. 2, pp. 162-166.

Ratheet, C, Williams, ES, McCaughey, D & Ishqaidef G 2015, ‘Patient perceptions of patient-centred care: empirical test of a theoretical model’, Health Expectations, vol. 18, no. 2, pp. 199-209.

Saha, S, Beach, MC & Cooper, LA 2008, ‘Patient centeredness, cultural competence and healthcare quality’, Journal of National Medical Association, vol. 100, no. 11, pp. 1275-1285.

Simmons, L 2009, ‘Dorthea Orem’s self care theory as related to nursing practice in hemodialysis’, Nephrology Nursing Journal, vol. 36, no. 4, pp. 419-421.

Watson, J 2008, ‘Social justice and human caring: a model of caring sciences as a hopeful paradigm for moral justice for humanity’, Creative Nursing, vol.14, no. 2, pp. 54-61.

Watson, J 2010, ‘Caring science and the next decade of holistic healing: transforming self and system from the inside out’, Beginnings, vol. 30, no. 2, pp. 14-16.