The modern world is teeming with technology to the point that detailed exploration of space bodies, electric machines, supersonic rockets, and everyday electronic devices no longer seem like something fantastic. In the pursuit of scientific progress, humanity has turned its gaze to the sky, forgetting what remains out of sight. The truth is that with every milliliter of seawater, all aquatic creatures and humans are gradually being poisoned by plastic waste.

In the post-industrial era, plastic production has become so plentiful that its surplus production cannot be recycled everywhere and is therefore dumped by the tons into the marine strata. This paper will repeatedly affirm that plastic littering of aquatic ecosystems is a critical mistake of humanity, as it entails severe problems for the entire biosphere. The purpose of this essay is to present science-based facts in support of the author’s words to convince the reader of the criticality of the ecological problem.

The best strategy for studying the problem of plastic pollution is to be familiar with the source of the phenomenon in general. Plastic waste is an integral part of companies’ production processes, and therefore it would be pointless to expect total elimination of waste. It is in the interest of manufacturers to reduce raw materials so that it raises the overall operational efficiency, but it is also in the interest of the manufacturer to create a corporate image of a nature-conscious production. This is why the green business industry has grown so enormously in recent years, encouraging manufacturers to be resource-efficient and environmentally responsible.

As a result, today’s companies are looking for a way to effectively recycle plastic waste in a way that meets the social demands of ecological communities. The difficulties begin when an entrepreneur looks for such a way: globally, no more than thirty percent of plastic waste is recycled, with the major centers of adequate recycling being developed countries (EPA). Consequently, plastic businesses from poor or developing countries cannot afford to recycle the materials profitably, and therefore the cheapest and least expensive solution is to dump plastic waste into water systems illegally.

In turn, plastic litter in marine ecosystems poses several critical threats not only to the aquatic environment but to the biosphere as a whole. This statement is not unsubstantiated or subjective but has been repeatedly confirmed by independent groups of researchers working in different fields of oceanography and ecology (Kurtela and Antolovic 55).

First of all, it should be noted that plastic sediments in water do not necessarily sink to the bottom but instead can float either in the thickness or on the surface of the sea. This phenomenon has two negative factors for aquatic creatures at once. On the one hand, when fragments of large plastic are free-floating in the water column, hydrobionts often mistake it for a victim. This leads to the entanglement of marine organisms in plastic nets (Figure 1) and, as a consequence, death due to the inability of functional viability.

On the other hand, plastic debris in ocean waters has detrimental effects on plant life in ecosystems as well. As it is known, plastic drifting on the surface tends to aggregate into conglomerates so as to form large clusters. One of the largest such conglomerates is Plastic Island, which has an area of 1.6 million square kilometers, just six times the size of the United States (ABC News). Thus, this substantial plastic patch prevents sunlight from penetrating the water column, depriving aquatic organisms of a vital source for existence. Plants that do not receive sufficient light cannot photosynthesize, and as a consequence, die. In turn, reduced photosynthetic intensification disturbs the balance of chemicals in the environment, leading to the death of animals.

Nevertheless, the problem of plastic waste is not only the accumulation and obstruction of marine life. On the contrary, the key and the most discussed threat from plastic is not visible but invisible to the human eye: it is microplastics. Microplastics are tiny particles of plastic, no larger than 5 mm in size. Such particles are formed either as a result of natural breakdown by light or by constant abrasion due to the mechanical action of waves. As a result, billions of tiny particles are suspended in the water and penetrate all livings either through nutrition or adsorption on the skin.

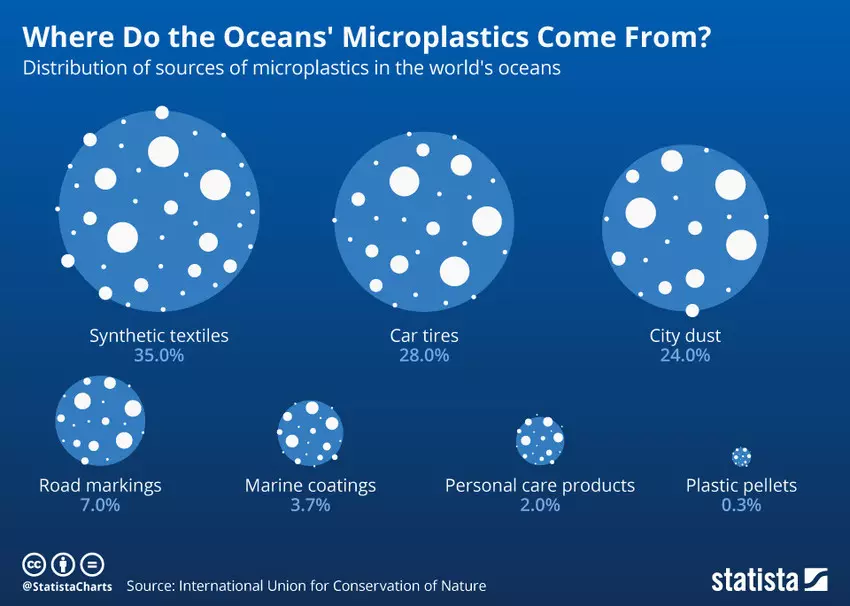

It is a mistake to think that microplastics are a myth or an imaginary threat. A minimum estimate is that 51 trillion microplastic particles — which, by the way, is twice the number of micro fragments — were in the world’s oceans in 2020, and this number is only expected to grow (Condor). Microplastics have several pathways into aquatic environments: in addition to the already mentioned degradation of large parts, textile compounds, car tires, urban dirt, and cosmetics should be noted (Figure 3). Each of the described sources contributes to the contamination of the seas through natural cycles, which means that it is extremely difficult to trace the specific pathway of microparticles.

In fact, by now, the academic community lacks a formed vision of the problem of microplastic buildup in organisms. While recognizing the deposition of particles in the digestive, respiratory, and even reproductive systems, researchers have sought to determine the negative effects of plastic (Bour et al. 1220).

In doing so, general considerations make it clear that such fragments in a fish, turtle, squid or human above the rest in the trophic chain are not body-neutral. First of all, the abrasive properties of microplastic particles can negatively affect the integrity of the body’s soft tissues. Acting like a scrub, microplastic particles have the potential to scratch internal organ walls, initiating blood loss and ulcers. Second, microplastics tend to absorb toxic substances, especially chemical toxins, whether oil or organic solvents from industries. When a particle enters the body, microplastic will release poisons outward, poisoning the host body from within.

To form a fairer view, alternative points of view should be considered. Although the existence of microplastic cannot be denied, there is still no reproducible evidence in favor of its unconditional harmfulness to the body. In addition, although microplastics have been shown to be transmissible from predator to prey, such observations have not yet been published for humans (Athey et al. 160). Finally, urban dwellers are already in constant contact with the billions of polluted particles that form the atmosphere of urban centers. City dust, machine exhaust, and industrial waste all combine to poison the lives of urban dwellers, and so the threats from microplastics, while they may be relevant, seem excessive.

Nevertheless, the lack of direct evidence does not mean that there is no real problem. Microplastics exist, and the question of their adverse effects on organisms will likely be resolved in the next decade. Even now, society should take the first steps to inhibit the amount of plastic waste. This can be accomplished both by changing individual consumer behavior and by forming bills to limit the possibilities for illegal dumping of waste.

In conclusion, it bears repeating that among the environmental problems associated with marine systems, plastic is one of the central ones. Plastic, in both macro and micro forms, has serious adverse effects on the health of marine ecosystems. The plastic itself has been shown to be a severe hazard to marine systems. First of all, it concerns the creation of significant conglomerate accumulations, which prevent sunlight from penetrating the water column.

In addition, floating plastic causes animals to become entangled in it and die. On the other hand, microplastics are an equally pressing threat with their invisibility to the human eye. Microplastics can accumulate in the body and probably lead to serious health problems. Given the connectivity of biological environments, problems with the seas will undoubtedly respond to other systems as well, leading to a global biosphere crisis. To prevent such a scenario from being reinforced, both individual and state behavior regarding plastics needs to be addressed.

Works Cited

ABC News. ” ‘Great Pacific Garbage Patch’ is Massive Floating Island of Plastic, Now 3 Times the Size of France.” ABC News. 2018. Web.

Athey, Samantha N., et al. “Trophic Transfer of Microplastics in an Estuarine Food Chain and the Effects of a Sorbed Legacy Pollutant.” Limnology and Oceanography Letters, vol. 5, no. 1, 2020, pp. 154-162.

Bour, Agathe, et al. “Presence of Microplastics in Benthic and Epibenthic Organisms: Influence of Habitat, Feeding Mode and Trophic Level.” Environmental Pollution, vol. 243, no. 2018, pp. 1217-1225.

Chias, J. ” For Animals, Plastic Is Turning the Ocean into a Minefield.” National Geographic. 2020. Web.

Condor. “Statistics 2020-2021.” Condor Ferries. 2021. Web.

EPA. “Plastics: Material-Specific Data.” US Environmental Protection Agency. 2021. Web.

Kurtela, Antonia, and Nenad Antolović. “The Problem of Plastic Waste and Microplastics in the Seas and Oceans: Impact on Marine Organisms.” Croatian Journal of Fisheries, vol. 77, no. 1, 2019, pp. 51-56.

RESET. ” Plastic Ocean — The Great Pacific Garbage Patch.” RESET. 2020. Web.

Wood, Johnny. “The Ocean is Teeming with Microplastic — a Million Times More than We Thought, Suggests New Research.” WEF. 2019. Web.