Abstract

Research is scant which may suggest or indicate any existing relationship between Asian students living in Australia and their political inclinations. Very little information regarding the political view of Asian students, aged 18-26 years are known or their views regarding the controlling of petrol prices and compulsory education. This study explores the views of international Asian students studying in Australia regarding politics, price control of petrol, and compulsory educational system. This paper will provide a bird eye view of the Asian political inclinations in Australia and their authoritarian constructs.

The research hypothesis that we studied is “an overseas Asian student living in Australia, aged 18-26, who is anti-capitalist authoritarian, would be in most favour of policies that make education compulsory and control petrol prices out of all 4 political categories.” The four political categories which were defined to demonstrate the inclinations are anti-capitalist authoritarian, anti-capitalist libertarian, pro-capitalist authoritarian and pro-capitalist libertarian.

The methodology used to conduct the research was an exploratory questionnaire survey method. The results of the study provided inconclusive results as our research findings showed that the person most in favour of such policies was an anti-capitalist authoritarian and the person least in favour was also an anti-capitalist authoritarian. As a result we may say that the result of the survey did not produce any significant result.

Our study was limited in its scope as the sample size thus selected was very small to reach any conclusive decision regarding the Asian student’s behaviour. Due to a very small sample the results of the survey may have been biased and inconclusive. This limitation provides scope for further research in the area.

Introduction

Political beliefs shape the beliefs and support for a certain policy and culture is an influencing factor in shaping such construct. The question of anti-capitalist being more authoritative and supports government price control of petrol and compulsory education system has gained low academic attention. Especially the researches in this area is scant when we further narrow our scope of study to Asian students aged 18-26.

Asian ideologies or the so called “Asian values” which has historically shown an inclination towards anti-capitalist politics and support for authoritarian structure and policies (Whatever happened to “Asian Values”?, 2001). The Asian political views have supported anti-capitalist, socialistic government with strict government control of the economy. Examples of such economies are China, Indonesia, Malaysia, etc.

With an increasing number of Asian students in Australia which rose from 77 percent of the total international students enrolled in 2002 to 81 percent in 2008 (AEI, 2008), it is important to understand the political views of the international Asian students in the campuses of the country so that their political beliefs and ideas can be considered and kept in mind while approaching them and help them to acclimatize.

This becomes more important due to the extreme right stand of Australia (THE OTHER RADICALISM: AN INQUIRY INTO CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN EXTREME RIGHT IDEOLOGY, POLITICS AND ORGANIZATION 1975-1995, 1999) and relatively left stand of the Asians (Who is “us”? Students negotiating discourses of racism and national identification in Australia, 2003; Whatever happened to “Asian Values”?, 2001). So a study to understand the correlation is important.

Numerous studies have been set up to examine students’ views on racism and racial and ethnic difference and identities (Who is “us”? Students negotiating discourses of racism and national identification in Australia, 2003)but very few study exist which concentrates on ascertaining the relation between the political inclination of international Asian students and their views regarding authoritarian government policies. The aim of this survey was to test the validity of our hypothesis. Our hypothesis for this survey was: “an overseas Asian student living in Australia, aged 18-26, who is anti-capitalist authoritarian, would be in most favour of policies that make education compulsory and control petrol prices out of all 4 political categories.”

Policies and regulations are supposed to have an impact on students from various nations and their views and ideas regarding an existing and a new policy is important to understand in order to determine the support or need for reform for such policies. Australia has a compulsory educational policy, which had been enforced in 1870 (McCreadie, 2007). As this educational law is very old, it is important to understand what students think about such a law in order to evaluate its redundancy.

Further, with the recent phenomenon of spiralling oil prices, the Rudd government has agreed to control prices of fuel in the country (Wilson, 2008) it is important to understand how a student from an anti-capitalist authoritarian origin would respond to.

Clearly the anti-capitalist political views which have been the general political views of Asians (Whatever happened to “Asian Values”?, 2001; Who is “us”? Students negotiating discourses of racism and national identification in Australia, 2003) and the relation it has to an existing law of compulsory education and current possible government control of prices. This would bring us to view the political idea Asians students have. Given this background we constructed our hypothesis which states that “an overseas Asian student living in Australia, aged 18-26, who is anti-capitalist authoritarian, would be in most favour of policies that make education compulsory and control petrol prices out of all 4 political categories.”

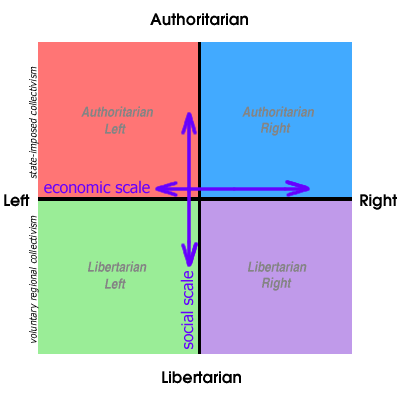

The four political categories we intend to identify amongst the Asian students are anti-capitalist authoritarian, anti-capitalist libertarian, pro-capitalist authoritarian and pro-capitalist libertarian. An anti-capitalist authoritarian is someone who wants the government to have full control in areas of personal issues and the economy. A pro-capitalist libertarian is the opposite. He/she wants society to have complete freedom and feels that the government should not control anything at all.

An anti-capitalist libertarian is someone who wants freedom in their personal issues, but wants the government to control the economy. Whereas a pro-capitalist authoritarian is someone who wants a free market but wants the government to control personal issues (McCreadie, 2007).

The hypothesis is specific in demonstrating it target sample which is Asian students within the age group of 18-26 years. We were specific in choosing this target sample as there has been a marked increase in Asian international students in Australia within this age group. Statistics has shown that in 2008 there has been a student’s commencement o f79 percent as opposed to 74 percent in 2002. Such increase has increased the availability of Asian students in campuses which would facilitate our data collection procedures.

The hypothesis was tested by analysing the data collected through a questionnaire based exploratory survey. The questionnaire was designed to ascertain the respondents’ political views and to determine whether a person was authoritarian or libertarian. The questionnaire aimed to understand if they agreed to a controlled regime which would indicate them to be authoritarian or they wanted to enjoy a free reign which would prove them to be libertines. Another set of question was framed to understand the political inclination of the respondent (McCreadie, 2007).

The limitation of the study was in its scope of study as the sample which was actually questioned was very small to reach any conclusive and generalizable solution. The significance of the study lies in its approach and finding. It would indicate the political inclination of the students as well as their view regarding the policies of the government. Further it would help us to understand if Asians still believed in an authoritarian culture and was there any relation with this belief and their political inclinations. In the next section we discuss the methodology applied to undertake the study and the analysis of the data.

Methods

Respondents

The survey yielded 20 responses. The respondents were international Asian students within the age group of 18-26 years studying in Australia. The reason for choosing this target sample group is due to the increased number of Asian students studying in Australian universities which official data says to be 79 percent for 2008 (AEI, 2008).

Sampling Design

A convenience sample was chosen from among the population of international Asian students studying in Australia. The number of respondents was chosen to be 20 from among the known Asian students for our convenience.

Questionnaire Design

The questionnaire developed was formed on a 4-point Likert scale with ratings ranging from “strongly agree” to “strongly disagree”. The questionnaire asked demographic information regarding the respondent’s age, sex education status and name. The questionnaire was separated into two parts. The first ten questions were used to determine the political views of an individual and the next ten questions were about the individual’s personal views towards certain policies. The questions we used were easy to understand and were ‘unloaded’ questions.

Procedure

The hypothesis for the research was built through a brief background study of the culture and political literature. To test the hypothesis we framed an exploratory study which was conducted through a questionnaire based study. The survey was divided in groups of three to facilitate interaction with the respondents with the researchers. There was a deciphering problem which was faced with question 5 which had to be explained to the respondents. After interviewing 20 respondents, results were compiled to determine political views and views on policies in our hypothesis, using the Political Compass (Pace News Limited, 2008).

This will be furthered explained in the results section. Also to see if there really was any bias from our respondents, Louis gave his respondents the same survey twice, this time, he promised to buy them dinner if they took it seriously. When their response came back, their political views had changed. This revealed that there was biasness from our respondents.

Limitations

Investigator Bias

An investigator’s bias implies that erroneous interpretation of the research data when the interpretation of data is not objective. Also, this may indicate that the researcher’s questions were biased or ‘leading’. Due to lack of objectivity of data interpretation the result of the survey becomes biased. This is because we would tend to only view the data in ways that could fit our hypothesis and disregard data that reject our hypothesis. Further, when questions are biased or misleading, respondents may not have a much of a choice and have to choose an option they may not truly agree with. This will cause the results of the survey to be inaccurate as the true views of the respondent cannot be made certain.

Social Desirability Bias

Respondents may answer in ways that they think will please us. They may also not answer truthfully because they do not want to appear ignorant or prejudiced. This will also cause the results of the survey to be inaccurate as respondents may not reveal their true views or feelings towards certain views out of fear or compliance.

Truthfulness of Participants

Respondents may not take the survey seriously, they may deliberately answer wrongly or purposely omit answers for certain questions, as can be seen by what Louis did in the Procedure section. This will cause the results in the survey to be incomplete and thus, inaccurate.

Limitations imposed by assignment

Time constraint, sample size is too small and sampling is not randomized. Time constraint limits the quality of work we can produce. With so little time, sufficient information cannot be gathered and surveys can only be carried out on a small sample size. With a small sample size, results from the survey cannot be taken seriously as it may be inaccurate. This is because it is nonsensical of us to make a prediction on several thousands of people based on only 20 respondents. Also, our sampling was not really randomized. This is because we surveyed people we already knew, and thus, our population might be biased already.

Results

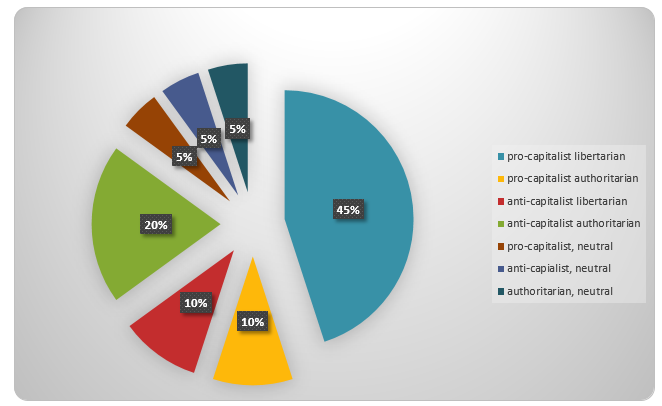

The method used for analysis of the data is a tool called Political Compass (Pace News Limited, 2008), we tried to ascertain the inclinations of the respondents regarding politics and policies. The four categories which we tried to place them in are pro-capitalist libertarian, pro-capitalist authoritarian, anti-capitalist libertarian or anti-capitalist authoritarian. But in the course of our research we identified three more groups who were pro-capitalist: neutral, anti-capitalist: neutral and authoritarian: neutral. Clearly these people had political inclinations but no view regarding the policies in place or to be imposed. This implied that their political views did not affect their viewpoint regarding policies.

Figure 2: Views on Policies by Respondents.

The questionnaire was designed to ascertain both the political as well as the respondents’ idea about the policies. This was done by using questions 1, 4, 6, 7 and 9 to determine whether a person was a pro-capitalist or non-capitalist (x-axis). Questions 2, 3, 5, 8 and 10 to determine whether a person was an authoritarian or libertarian (y-axis). The ratings were codified by quantifying the responses wherein we quantified ‘strongly agree/disagree’ as 1 which implied that the direction of response was moving in the direction of north, south, east or west, depending on the question. If they circled the option ‘agree/disagree’ then they gained 0.5 points moving in one of the four directions as well.

The overall score for each axis was gained by taking the greater number of points moving in a certain direction and subtracting the number of points going in the opposing direction (see figure 1). For example, 3N-2S= 1N. Therefore, the person is authoritarian. Doing this for each respondent for the first 10 questions allowed us to determine where they were on the Political Compass and thus their political view.

Discussion

Methodology

The research was an exploratory study of the political views and their authoritarian constructs and their influence on their viewpoints regarding the government policies. The methodology employed was to conduct a questionnaire based survey. The questionnaire consisted of 20 questions. The questions aimed to ascertain the political inclination of the respondents, to determine if they were authoritarian or libertines and what views they held regarding the educational and fuel price control policies.

The data was collected through traditional method when the questionnaire was filled in and interviews were conducted simultaneously to solve any problem the respondents faced while answering the questionnaire. The survey was conducted among Asian students studying in Australia within the age group of 18-26 years.

The data was analysed using Place Compass which was a shift from the old one dimensional ‘left-right’ line (Pace News Limited, 2008). The grid thus developed considers political social and economic dimensions of the respondent in the grid and evaluates his/her position on this basis (see figure 1).

Data

The data was collected from an Asian student group of age 18-26 years who were chosen by convenience sampling. The sample size was small, i.e. 20. The data was collected through questionnaires which consisted of 20 questions. There were ten questions, 1,4, 6, 7, and 9 to determine whether a person was a pro-capitalist or non-capitalist and another set of ten questions, 2, 3, 5, 8 and 10 to determine whether a person was an authoritarian or libertarian.

Results

From the analysis of the data collected through the survey we see that the hypothesis which stated the Asian students who were anti-capitalist would show authoritarian traits was found to be inconclusive. This is so because only 4 out of the 20 respondents were anti-capitalist authoritarians! Majority of our respondents were pro-capitalist libertarians. Further, our research also revealed that there were respondents who were neutral to the government policies thus discussed in the research. The data analysis revealed several respondents who were placed on one of the axis. Thus, those who were neutral were placed into separate groups, as can be seen in our pie chart (see figure 3).

Interestingly, there was an individual who was an anti-capitalist authoritarian and had a neutral view on the policies. Further other contradictory views that we collected showed respondents to be an anti-capitalist authoritarian, was most in favour of the policies. On the contrary, the person who least favoured the government policies was also an anti-capitalist authoritarian (-3 out of a possible -5). There was also another anti-capitalist authoritarian who had neutral views on the policies. This is interesting as we would expect an anti-capitalist authoritarian to be in favour of policies that were authoritative.

From our results, we also found that majority of the pro-capitalist libertarians were not in favour of our policies. Their personal choices coincide with their political views. However, for a particular pro-capitalist libertarian, that person was in favour of our policies, he/she scored a 4.5 out of the total of 5. This too is surprising, as the political views do not coincide with the personal views. Apart from these interesting findings, the pro-capitalist authoritarians were in mild favour of our policies, as expected, scoring a 1.5 and 3. For the anti-capitalist libertarian, they were either mildly against (-1.5) or mildly for (2) our policies as expected as well.

Thus from the results obtained, there is no confirmed relationship between an anti-capitalist authoritarian and policies that control petrol prices or policies that make education compulsory. Hence we cannot accept the hypothesis taken in the research regarding Asian students. The research to a great extent shows that Asian political views and power construct was inconclusive which supports the theory of a new Asian political idea emerging which is pro-capitalism (Whatever happened to “Asian Values”?, 2001).

Conclusions

The research demonstrated that the political ideals of Asian students did not show any significant correlation with that of their power construct and support for government policies. But the inconclusiveness of the research findings may be due to the small sample size which led to skewed data collection.

To summarise our research findings we may say that the individuals who were anti-capitalist authoritarians. One of which was most in favour of authoritative policies, while the other was the least in favour. However, this should not be used as a generalisation as our research sample size was too small and the results cannot be used to predict the political views of all international students from Asia. Also, it can be said that a person’s political view does not always determine their personal views on certain policies.

Bibliography

AEI. 2008. International Student Data for 2008. Australian Education International. Web.

McCreadie, M. 2007. The Evolution of Education in Australia. IFHAA Australian Schools. Web.

Pace News Limited. 2008. The Political Compass. Pace News Limited. Web.

THE OTHER RADICALISM: AN INQUIRY INTO CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN EXTREME RIGHT IDEOLOGY, POLITICS AND ORGANIZATION 1975-1995. Saleam, James. 1999. Unpublished PhD. Thesis, University of Sydney.

Whatever happened to “Asian Values”? Thompson, Mark R. 2001. Journal of Democracy Volume 12, Number, pp. 154-168.

Who is “us”? Students negotiating discourses of racism and national identification in Australia. McLeod, Julie and Yates, Lyn. 2003. Race, Ethnicity and Education 6 (1), pp. 29-49.

Wilson, T. 2008. Taxes key to petrol prices. ABC News. Web.

AEI. 2008. International Student Data for 2008. Australian Education International. Web.

McCreadie, M. 2007. The Evolution of Education in Australia. IFHAA Australian Schools. Web.

Pace News Limited. 2008. The Political Compass. Pace News Limited. Web.

THE OTHER RADICALISM: AN INQUIRY INTO CONTEMPORARY AUSTRALIAN EXTREME RIGHT IDEOLOGY, POLITICS AND ORGANIZATION 1975-1995. Saleam, James. 1999. Unpublished PhD. Thesis, University of Sydney.

Whatever happened to “Asian Values”? Thompson, Mark R. 2001. Journal of Democracy Volume 12, Number, pp. 154-168.

Who is “us”? Students negotiating discourses of racism and national identification in Australia. McLeod, Julie and Yates, Lyn. 2003. 2003, Race, Ethnicity and Education 6 (1), pp. 29-49.

Wilson, T. 2008. Taxes key to petrol prices. ABC News. Web.