Introduction

Preferential treatment of minority group members continues to be a controversial yet sometimes necessary ingredient in equal opportunity employment. Managers recognize the increasing diversity of the workforce and the need to fully utilize its members. Furthermore, fulfillment of equal opportunity employment requirements and use of voluntary affirmative action plans have become essential, if not obligatory, elements of everyday human resource procedures.

The growing number of women represented in the workplace, and in managerial positions in particular, have made it essential to understand possible hindrances to women’s organizational effectiveness in response to preferential employment practices. Such practices have been shown to have unintended negative effects, both on individuals’ perceptions (of self and others) and behaviors. These perceptions and behaviors can often translate into negative consequences for the organization, as will be explored in this paper.

The purpose of this study is to examine whether preferential treatment has effects on subordinate attitudes and behaviors in a task setting, e.g. in evaluations of their leaders, commitment toward leader-assigned goals, and in subordinate task performance. In addition, the effects of stereotypical views toward women as managers in leader evaluations, subordinate commitment and subordinate performance are explored.

Preferential Treatment

Previous preferential treatment studies have concentrated on either individual self-perceptions or perceptions of others who have been treated in a preferential manner. In many empirical studies, preferential selection has been shown to negatively affect individuals in self-reports of organizational commitment, role stress, satisfaction, self-perceptions and evaluations, and task selection (Chacko, 1982; Heilman and Herlihy, 1984; Heilman, Lucas, and Kaplow, 1990; Heilman, Rivero, and Brett, 1991; and Heilman, Simon, and Repper, 1987). Females selected preferentially have evidenced more negative self-views than in merit-based situations. Preferential treatment has resulted in women’s lower self-evaluations of performance, leadership ability, and future desire to lead (Heilman et al., 1987).

Individuals may also differ in their perceptions of others who have been treated preferentially and of the organization that acted preferentially. The amount of discrepancy in merit between candidates when a less qualified minority candidate is preferentially selected has been shown to affect the level of perceived injustice felt by the more qualified majority candidate (Singer and Singer, 1991).

Perceived fairness of the selection process may also negatively influence beneficiaries of affirmative action in their attraction to certain organizations (Nacoste, 1987) and in reactions to individuals (e.g. job applicants) similar to themselves (Heilman, Kaplow, Amato, and Stathatos, 1993). These findings highlight the paradox of affirmative action programs – they may often harm the very individuals that they are designed to help.

Leader Evaluations

The evaluation of female leaders may also be detrimentally affected by their preferential appointment. Jacobson and Koch (1977) conducted a laboratory experiment involving the preferential, chance, or merit selection of a female confederate as leader in a dyad with a male subject. They found that the more equitable the method of leader selection, the more positively the subject rated the confederate’s performance and the more credit she received for success.

A leader’s source of authority, or legitimacy, may predict evaluation of his or her leadership effectiveness (Read, 1974; House and Baetz, 1979). A follower must not only perceive that a behavior is an influence attempt – he or she must also view the attempt as acceptable. If the influence attempt is not accepted by the perceiver, then the leader’s authority is not legitimized.

Goal Commitment and Subordinate Performance

One important component of leader legitimacy is real or perceived leader competence (Read, 1974). This component may prove perplexing in a preferential treatment situation. A preferentially selected leader may be viewed as less legitimate because competence is not perceived as a basis for selection. The leader’s task competence may truly be adequate, but this competence has not been validated in the selection process. Subordinates may perceive the leader as less qualified, and subordinate commitment to the leader may suffer.

Goal setting is most likely to improve task performance to the extent that subordinates accept leader assigned goals (Locke, Shaw, Saari, and Latham, 1981). Goal acceptance, however, is necessary but not sufficient for goal commitment. Goal commitment (i.e. the individual feeling bound to achieving the goal), is necessary for goal setting to be an effective motivational tool and is critical in predicting performance (Hollenbeck and Klein, 1987).

We would expect goal commitment to be reduced in the case of preferential leader selection, as a leader’s legitimate authority is undermined. Lessened goal commitment by subordinates may translate into ensuing performance decrements. The extent to which subordinates perceive leaders to be legitimate will be positively related to the subordinates’ commitment to goals assigned by that leader. In turn, goals will most likely improve performance only to the extent that subordinates are committed to such goals.

From the preceding discussion on preferential treatment, we expect to find that preferential selection of a female into a leadership position will lessen subordinates’ feelings of commitment to both the female leader and to goals assigned by that leader, translating into a decrease in performance level. We have seen that preferential treatment negatively affects many individual perceptions, regardless of gender. We would therefore predict no significant difference in reaction based on gender of the subordinate. We thus expect to see a negative impact of preferential selection on subordinate evaluations of the female leaders, regardless of subordinate gender.

Additionally, we expect to find that subordinate commitment to goals assigned by the female leader will be lessened in a preferential treatment situation. Last, we expect to observe lower task performance by subordinates because of lessened commitment to the leader-assigned goals. Our formal hypotheses are as follows:

- Hypothesis one: Subjects will assign lower scores of leader effectiveness to a preferentially selected female leader than will subjects in a merit selection condition.

- Hypothesis two: Subjects will exhibit significantly lower levels of commitment to goals assigned by a preferentially selected female leader than will subjects in a merit selection condition.

- Hypothesis three: Subjects whose leaders have been selected preferentially will exhibit lower task performance than that of subjects in a merit selection condition.

Stereotypical Beliefs About Women as Managers

An additional complication in the affirmative action arena stems from gender-based views in the workplace and the effects of these views on evaluation of female employees. Most managerial jobs have been attributed masculine characteristics, i.e. they have been male “sex-typed” or gender-typed. Congruence of job and gender characteristics in gender-typed occupations stems from the differences in specific personality traits assigned to men and women and the judged appropriateness of those characteristics on the job. For example, assertiveness is viewed more as a male trait, while passivity is seen as a female trait (Locksley, Borgida, Brekke and Hepburn, 1980). These attribute differences have led to a widespread notion that men may possess more of those attributes viewed as necessary to succeed at work (Heilman, 1984).

It has been found in separate studies of male and female middle managers that successful managers are perceived to possess characteristics, attitudes and temperaments more commonly ascribed to men in general than to women in general (Heilman, Block, Martell and Simon, 1989; Schein, 1973, 1975). Men are perceived as more aggressive and independent. Women are viewed as more tactful, gentler and quieter.

Congruence between gender-typed jobs and gender-typed tasks has been shown to affect performance ratings (Barnes-Farrell, L’Heureux-Barrett, and Conway, 1991; Eagly, Makhijani, and Klonsky, 1992; Stoppard and Kalin, 1983). In general, men have been found to receive more favorable evaluations than women (Deaux and Emswiller, 1974; Garland and Price, 1977; Nieva and Gutek, 1981). Deaux and Emswiller (1974) found that performance by a male on a “masculine” task was attributed to skill, while an equal performance by a female was attributed to luck. The reverse did not hold for a feminine-related task.

Garland and Price (1977) measured male undergraduates subjects’ attitudes toward women in management, using Peters’ et al.’s Women as Managers Scale (WAMS; Peters, Terborg and Taynor, 1974, as cited in Garland and Price, 1977). They found that the description of success for a female manager was attributed to external factors (i.e. luck) by those subjects with low WAMS scores (representing more traditional views of women). Likewise, those subjects with high WAMS scores (i.e. less traditional attitudes toward women managers) attributed success to the woman’s internal factors (ability and effort). The WAMS scale is essentially measuring an individual’s stereotypical views about women’s ability to be effective managers.

A second aim of this study was to explore the role of stereotypical beliefs on reactions to a female leader and the goals she assigns. Individuals with more traditional stereotypical beliefs about females typically score lower on the WAMS scale. We posit that higher levels of stereotypical beliefs regarding the female role in the workplace (i.e. lower WAMS scores) will negatively impact subordinates’ evaluation of female leaders and commitment toward goals assigned by these leaders, as well as negatively affecting subordinate performance. From the preceding discussion, our next hypotheses are:

- Hypothesis four: Subjects’ scores on the WAMS measure will be positively related to their evaluations of the leader’s effectiveness.

- Hypothesis five: Subjects’ scores on the WAMS measure will be positively related to commitment to leader-assigned goals.

- Hypothesis six: Subjects’ scores on the WAMS measure will be positively related to subordinates’ task performance.

In addition, it is possible that interactions exist between our preferential treatment variable and WAMS scores. A subject with more traditional stereotypical views of the female role, for instance, might feel more negatively toward the use of preferential treatment than would a subject with less traditional views. We would predict that lower WAMS scores interacting with preferential treatment would have an even more negative effect on goal commitment, leader evaluations, and performance. Therefore, we will also explore whether such interactions are significant.

Method

Subjects

Our sample consisted of 135 undergraduate students enrolled in a junior level management class during the Fall 1992 semester at Texas A&M University. The students participated in the laboratory experiment for extra credit points. Participants included 69 males and 66 females. Although race/ethnicity information was not collected, the class from which the sample was taken is typically homogeneous – approximately 98% white.

Task

Students worked on a class scheduling task in which they were to develop non-redundant schedules involving five courses offered at various times. They completed both a ten minute practice trial and a fifteen minute experimental trial. This type of task is both highly familiar and has high face validity to students (Earley and Kanfer, 1985) and is often used in goal-setting studies.

Variables

Manipulated Variable

Preferential Treatment. Preferential treatment was operationalized after administration of two tests purported to assess leadership ability. The experimental manipulation took place as the lab instructor collected the two tests for scoring. While the subjects completed an additional scale (a self-esteem measure), the lab instructor enacted one of two scenarios (determined at random by a coin toss prior to the laboratory session). In the merit selection condition, the instructor appeared to score the two measures and base leader selection on the highest test scores. The actual statement used by the instructor in this scenario was, “As stated before, the two tests you took were used to predict leadership effectiveness. Based upon the results of the tests, will be in the leadership position.”

In the preferential selection condition, the instructor did not attempt to score the tests. Instead, the instructor placed the tests aside and communicated that, “Although we wanted to place people in the leadership role based on ability we are experiencing a shortage of female leaders. Therefore, will be placed in the leadership role.” As noted, in both cases the female confederate was chosen as group leader.

The laboratory instructor was one of two graduate students, one male and one female, who conducted sessions on a relatively even basis. Four female undergraduate students alternated as the confederate. These students were familiarized with the lab scenario before the sessions took place, and they followed the same set script regardless of the session being preferential treatment or ability in nature. The operationalization of preferential treatment that was used is exactly like that used by Heilman and her colleagues (e.g. 1984, 1987, 1989, 1991, 1993) in which gender is used as a decision-making characteristic instead of ability.

Measured Variables

- Goal: The leader-assigned goal was operationalized as twice the amount of schedules that each student completed in his or her ten-minute practice trial, to be completed in the fifteen minute experimental trial. The set goal level should have been realistic to students as it was specifically based on initial performance in the trial. This goal was chosen so as to be perceived as both specific and difficult to the subjects, factors which have been established as leading to higher motivation and subsequent performance (Locke et al., 1981.)

- WAMS: The Women as Managers Scale devised by Peters, Terborg and Taynor, 1974 (Beere, 1990) is a twenty-one item scale that assigns scores on a numerical scale of one to seven, representing traditional to non-traditional stereotypes of women in business organizations held by the test subjects. The psychometric properties of WAMS have been demonstrated (Garland and Price, 1977). Coefficient alpha for the WAMS in our study was 0.92.

- Leader Effectiveness: The scale used by the students to evaluate the female leader included five items with a seven-point Likert scale format. An example item is, “The leader was clear in providing instructions in how to perform the task.” Coefficient alpha for this scale in our study was 0.75.

- Goal Commitment: The goal commitment scale used seven items from the scale developed by Hollenbeck, Williams and Klein (1989), measuring subjects’ commitment to the goal assigned by the female leader. The construct validity of this measure has been demonstrated (Hollenbeck, Klein, O’Leary, and Wright, 1989). Coefficient alpha in our study was 0.87.

- Performance: Performance was operationalized as the number of schedules completed by the subjects in the fifteen minute experimental trial.

Procedure

Students took part in a laboratory experiment lasting approximately one and one half hours. Three to five students were involved in each session, along with a female confederate posing as a fellow student. Students had signed up for laboratory times on posted sign-up sheets, resulting in a varying mix of male and female subjects in each of the sessions. The session began with an introduction by the lab instructor. Bookkeeping duties such as registering attendance, obtaining subject consent, and obtaining demographic data were performed. Next, two tests were administered to the subjects and the confederate, purportedly to determine selection of a group leader to guide the group in a simple class scheduling task.

The first test was the Wonderlic Personnel Test, which assesses general cognitive ability. The second test administered was the Leadership Opinion Questionnaire, which measures two facets of leadership (consideration and structure). Both of these tests have undergone extensive testing and are commercially available for research. Neither test was actually used to choose the leader as we utilized a confederate, although in the merit condition the lab instructor acted as though the tests were scored and used as the decision factor. In both the preferential selection and merit conditions, the confederate was then asked to lead the rest of the session.

The leader’s task was to guide the group through a class scheduling task. The task consisted of students being asked to write out sample schedules from a master schedule list, working independently. A ten minute trial scheduling task occurred, after which the leader checked on subjects’ progress and assigned individual goals for the actual fifteen minute class scheduling task. The goal was standard across laboratory sessions – twice the amount achieved on the ten minute trial run, to be accomplished in the fifteen minute actual run. Following goal assignment, the subjects were asked to complete measures of goal commitment.

Following the actual fifteen minute class scheduling task, the confederate was allowed to leave. Subjects were then asked to evaluate the effectiveness of the confederate in the leader role. The WAMS scale was also administered, followed by a manipulation check to observe whether the preferential selection condition was perceived as such by the subjects. Last, subjects were debriefed and were told that a full explanation of the study would be made available at its conclusion.

Results

Manipulation Check

Three items were included to check the preferential treatment manipulation (“The leader was chosen based on his/her performance on the leadership tests,” “The leader was chosen for non-job related reasons,” “The leader was chosen because of his/her sex”). The manipulation was checked by asking the subjects to rate these items from one (“strongly disagree”) to five (“strongly agree”).

Correlations for the first and third items with the preferential treatment condition were highly significant (-.55, p [less than].01 and.54, p [less than].01) but insignificant for the second item (.15, n.s.). It is possible that the students were confused by the inclusion of the term “nonjob” when the task was only a laboratory simulation. We felt that the significance of the other two items lent sufficient evidence that the manipulation worked.

Tests of Hypotheses

The preferential/merit selection manipulation was dummy-coded “1” for preferential treatment and “0” for merit selection for purposes of the analysis. The leader-assigned goal level was coded as twice the number of trial schedules completed. The measure of goal commitment was coded as a value ranging from one to five. Performance was coded as the number of schedules completed by each student in the actual fifteen minute exercise. Each student’s evaluation of leader performance was coded using the one to seven scale, as was the level of stereotypical beliefs as measured by the WAMS scale.

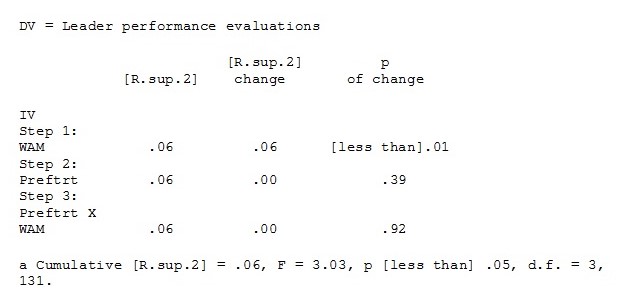

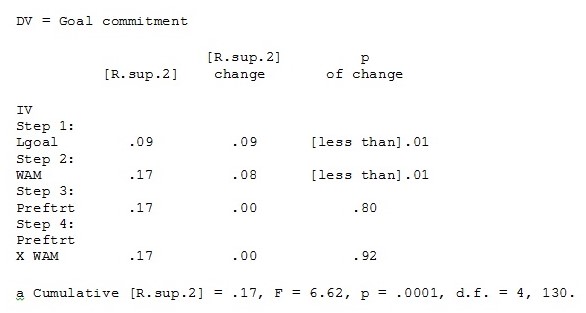

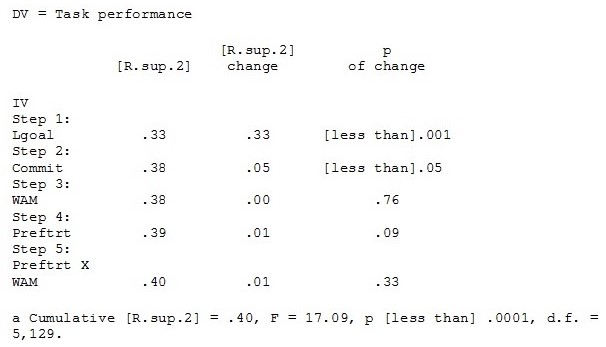

Data were analyzed using hierarchical multiple regression.(1) Results of these regression analyses are summarized in Tables 1, 2 and 3. Three different regression equations were completed. Equation one regressed leader effectiveness on WAMS scores in the first step, preferential treatment in the second, and a WAMS/preferential treatment interaction last. Equation two regressed goal commitment on leader-assigned goal level in the first step, WAMS scores in the second step, preferential treatment in the third, and a WAMS/preferential treatment interaction in the fourth step. Equation three regressed subordinate performance (number of schedules completed in the experimental trial) on leader-assigned goal level in the first step, goal commitment in the second, WAMS scores in the third step, preferential treatment in the fourth, and a WAMS/preferential treatment interaction last.

We did find significant two-tailed bivariate correlations between gender and the WAMS scale (-.51, p [less than].01), gender and goal commitment (-.20, p [less than].05), and gender and number of schedules completed (-.19, p [less than].05). We also found a significant one-tailed correlation between leader performance and gender (-.16, p [less than].05). The large association between gender and the WAMS scale appears to be driving these relationships, because WAMS scores are also significantly correlated with each of the above variables except for number of schedules completed. Controlling for WAMS, we ran partial correlations for gender, goal commitment, number of schedules, and leader effectiveness, and found that gender no longer had significant relationships with any of the other variables. We therefore felt comfortable with dropping gender from further analysis.

Hypothesis one stated that subjects would assign lower scores of leader effectiveness to a preferentially selected female leader than subjects in the merit selection condition. This was tested in step two of equation one, which showed that only 0.5% incremental variance in leader effectiveness scores was explained by the preferential treatment condition, which was non-significant. Thus, hypothesis one was rejected.

Hypothesis two stated that subjects would exhibit significantly lower levels of commitment to goals assigned by a preferentially selected female leader than subjects in the merit selection condition. This hypothesis was tested in step three of equation two. The incremental variance explained was 0.04% (n.s.), thus rejecting hypothesis two.

Table 1. Hierarchical Regression Analysis – Equation One.

Hypothesis three stated that subjects whose leaders had been selected preferentially would exhibit lower task performance than subjects in the merit selection condition. This was tested in step four of equation three, with an incremental 1.4% of variance explained (p =.09). Thus, hypothesis three was marginally supported.

Hypothesis four stated that subjects’ scores on the WAMS measure would be positively related to their evaluations of female leader effectiveness. This hypothesis was tested in step one of equation one, with variance explained equaling 6% (p [less than].01). Thus, hypothesis four was strongly supported.

Table 2. Hierarchical Regression Analysis – Equation Two(a)

Table 3. Hierarchical Regression Analysis – Equation Three(a)

Hypothesis five stated that subjects’ scores on the WAMS measure would be positively related to commitment to leader-assigned goals. This was tested in step two of equation two. Incremental variance explained was 7.5% (p [less than].001), thus strongly supporting hypothesis five.

Hypothesis six stated that subjects’ scores on the WAMS measure would be positively related to subordinates’ task performance. This hypothesis was tested in step three of equation three. The incremental variance explained was only 0.05% (n.s.), thus rejecting hypothesis six.

In addition, we examined in an exploratory fashion interactions between WAMS scores and preferential treatment. No interaction terms were significant in our regression equations.

Discussion

The present study examined the role of preferential treatment and stereotypical beliefs about women as managers in determining subordinate ratings of female leader effectiveness, commitment toward leader-assigned goals, and effects on subsequent subordinate performance. Previous evidence has established effects of preferential treatment on self-perceptions (e.g. Heilman et al., 1987) and some evidence exists that it may affect other organizational members’ perceptions and behaviors toward others (Heilman et al., 1993). In this study, however, only marginal effects of preferential treatment were demonstrated.

There are several possible explanations for our lack of preferential treatment effects. First, it may be that our manipulation was simply not strong enough to make a difference. In essence, the students’ instrumentality of being selected as the task leader may have been extremely low or even non-existent. Thus, a lack of reaction to the preferential treatment manipulation would not be surprising.

A second explanation involves the increasing trend toward “diversity” in both academic and business settings. It could be that the subjects viewed diversity as a legitimate goal, and thus preferential selection (e.g. using gender as a criterion) was seen as a legitimate means of selecting the leader. Given that students are consistently exposed to the diversity issue, it is possible that our subjects have internalized this goal as being completely legitimate. Obviously, this is a topic for future research.

The most interesting finding in this study is that WAMS scores were more influential than the presence of preferential selection on subordinate evaluations of female leaders as well as their commitment to the leader assigned goals. This has intriguing implications for organizations. If stereotypical beliefs influence such activities as leader evaluations and subordinate goal commitment, what may the effects be on other, more fundamental attitudes toward female managers such as perceived credibility?

If the same stereotypical biases are found to affect supervisors’ judgment of female subordinate capabilities, for example, it is possible that women’s opportunities could be significantly curtailed. Future research may even find that stereotypes may work indirectly through subordinate evaluations of female leaders to influence goal commitment and subsequent task performance. Perhaps stereotypes present a much larger, more pervasive problem for females in the workplace than that of preferential treatment policies.

This stereotyping effect could be detrimental to women’s self-esteem, much like the effects of preferential treatment. Although we did not find any preferential treatment effects in this study, prior evidence suggests that preferential selection may undermine a woman’s feelings of self-efficacy because she does not receive positive ability feedback (Bandura, 1977, 1982; Heilman, et al., 1990). This can be especially detrimental in male-dominated careers, such as management, where women have been shown to exhibit less self-confidence and to attribute success to external rather than internal factors (Lenney, 1981; McMahan, 1982). The effects of negative stereotypes may be similar, in that women may not receive positive information or positive outcomes if they are thought to be “inappropriate” for managerial roles. Stereotypes may in fact be more detrimental to women because they tend to operate in all situations, rather than being limited to preferential treatment cases.

A danger may then exist, especially when stereotypes are used, of a spiral effect of sorts in which females’ self-efficacy perceptions are lessened, translating into their lower performance. When combined with possibilities of subordinates’ lessened commitment and lower leader evaluations, female managers’ self-worth could conceivably slide further. Thus, a downward spiral occurs, and it would become imperative to break the cycle so that women would not lose the accomplishments that they have strived so diligently for. Of course, all of this is conjecture, and future research would need to address whether such a process happens in actual organizational situations.

The results of this study also certainly suggest that negative stereotypes about females in the managerial role have a negative impact on leader performance ratings. This may be thought of as error, e.g. lower performance ratings are received because of nonjob factors. In the same line of thinking, it may be that positive stereotypes may also introduce error in the form of inflated performance ratings. This is an extremely intriguing point for future research to address.

We did not find that stereotypical views influenced subordinate task performance in a direct fashion. This is evidenced by a non-significant bivariate correlation of .16 between WAMS and schedules. It is possible, however, that an indirect relationship exists between the two. In our second regression model, we found that higher WAMS scores (e.g. less traditional stereotypical views) translated into higher commitment to leader-assigned goals (e.g. hypothesis five). Furthermore, in our third equation we found that higher commitment significantly led to higher subordinate task performance. Our hypotheses did not explicitly include this type of mediating relationship. It appears that stereotyping works through goal commitment to influence task performance. Further analysis of this relationship in the future is warranted.

A potential weakness of the experiment is its laboratory setting. Laboratory experiments are considered less realistic and less generalizable to the “real” world. However, such experiments allow for greater control over the experimental manipulation, thereby possibly resulting in stronger relational effects. The use of student confederates most likely weakened the impact of the preferential treatment manipulation upon subjects’ goal commitment and leader evaluations. Subjects may have perceived the confederates as less legitimate because of age proximity and other similarities to themselves. Also, the leader role in this experiment may not have been viewed as desirable, unlike actual leadership positions in organizations.

Additionally, it may be that the strength of the stereotypical influences on our results stems from the more pervasive nature of those influences, i.e. in the absence of strong feelings about preferential treatment in the lab study, the students allowed their own personal attitudes toward women managers to play a larger role. Last, the short duration of the experiment does not represent well the on-going nature of organizational interactions.

Our study has implications for human resource policy. With increasing numbers of women in the workplace, the presence of glass ceilings, and the use of affirmative action, it is important to understand possible impediments that women may face in improving their positions in organizations. The possible hindrances resulting from stereotypes should not be taken lightly.

The necessity of affirmative action and equal employment opportunity ensures that women will have a place in organizational life. The demonstration of consequences to stereotypical beliefs, however, demands that we understand as much as possible the psychological processes underlying these consequences. Some evidence in our study combined with evidence of others (Heilman et al. 1987, 1993) points to some of the possible effects.

Future research should apply leader legitimization effects upon leader acceptance and evaluation, goal acceptance and goal commitment, and performance of subordinates in scenarios where women hold managerial roles. Since acceptance is critical to individuals’ commitment to goals, and since commitment theoretically leads to better performance, it is imperative that both stereotype and preferential selection effects be considered when selecting organizational leaders. This is not to say that these effects should prescribe elimination of minority promotion if such a promotion may be conceivably perceived as preferential treatment. As demonstrated by our study, this may not be the most important issue.

Rather, the organization should understand individuals’ perceptions of others in these situations. The organization should seek to provide information to employees which neutralizes potential negative perceptions of women as organizational leaders. Such information may at least lessen the impact of stereotyping, and at most it may alter stereotypical views and result in a more positive environment for women in leadership positions. Order entry of the WAMS and preferential treatment variables was arbitrary. The results do not change when variable order is changed.

References

Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191-215.

Bandura, A. (1982). Self-efficacy mechanism in human agency. American Psychologist, 37, 122-147.

Barnes-Farrell, J. L., L’Heureux-Barrett, T. J., & Conway, J. M. (1991). Impact of gender-related job features on the accurate evaluation of performance information. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 48, 23-25.

Beere, C. A. (1990). Gender roles: A handbook of tests and measures. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press.

Chacko, T. I (1982). Women and equal employment opportunity: Some unintended effects. Journal of Applied Psychology, 67, 119-123.

Deaux, K., & Emswiller, T. (1974). Explanations of successful performance on sex-linked tasks: What is skill for the male is luck for the female. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 29, 80-85.

Eagly, A. H., Makhijani, M. G., & Klonsky, B. G. (1992). Gender and the evaluation of leaders: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 111, 3-22.

Earley, P. C., & Kanfer, R. (1985). The influence of component participation and role models on goal acceptance, goal satisfaction, and performance. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 36, 378-390.

Garland, H., & Price, K. H. (1977). Attitudes toward women in management and attributions for their success and failure in a managerial position. Journal of Applied Psychology, 62, 29-33.

Heilman, M. E. (1984). Information as a deterrent against sex discrimination: The effects of applicant sex and information type on preliminary employment decisions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 33, 174-186.

Heilman, M. E., Block, C. J., Martell, R. F., & Simon, M. C. (1989). Has anything changed? Current characterizations of men, women, and managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 935-942.

Heilman, M. E., & Herlihy, J. M. (1984). Affirmative action, negative reaction? Some moderating conditions. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 33, 204-213.

Heilman, M. E., Kaplow, S. R., Amato, M. A. G., & Stathatos, P. (1993). When similarity is a liability: Effects of sex-based preferential selection on reactions to like-sex and different-sex others. Journal of Applied Psychology, 78, 917-927.

Heilman, M. E., Lucas, J. A., & Kaplow, S. R. (1990). Self-derogating consequences of sex-based preferential selection: The moderating role of initial self-confidence. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 46, 202-216.

Heilman, M. E., Rivero, J. C., & Brett, J. F. (1991). Skirting the competence issue: Effects of sex-based preferential selection on task choices of women and men. Journal of Applied Psychology, 76, 99-105.

Heilman, M. E., Simon, M. C., & Repper, D. P. (1987). Intentionally favored, unintentionally harmed? Impact of sex-based preferential selection on self-perceptions and self-evaluations. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 62-68.

Hollenbeck, J. R., & Klein, H. J. (1987). Goal commitment and the goal-setting process: Problems, prospects, and proposals for future research. Journal of Applied Psychology, 72, 212-220.

Hollenbeck, J., Klein, H., O’Leary, A., & Wright, P. (1989). An investigation of the construct validity of a self-report measure of goal commitment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 951-956.

Hollenbeck, J., Williams, C., & Klein, H. (1989). An empirical examination of antecedents of commitment to difficult goals. Journal of Applied Psychology, 74, 18-23.

House, R. J., & Baetz, M. L. (1979). Leadership: Some empirical generalizations and new research directions. Research in Organizational Behavior, I, 341-423.

Jacobson, M. B., & Koch, W. (1977). Women as leaders: Performance evaluation as a function of method of leader selection. Organizational Behavior and Human Performance, 20, 149-157.

Lenney, E. (1981). What’s fine for the gander isn’t always good for the goose: Sex differences in self-confidence as a function of ability area and comparison with others. Sex Roles, 7, 905-924.

Locke, E. A., Shaw, K. N., Saari, L. M., & Latham, G. P. (1981). Goal setting and task performance: 1969-1980. Psychological Bulletin, 90, 125-152.

Locksley, A., Borgida, E., Brekke, N., & Hepburn, C. (1980). Sex stereotypes and social judgment. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 39, 821-831.

McMahan, I. D. (1982). Expectancy of success on sex-linked tasks. Sex Roles, 8, 949-958.

Nacoste, R. W. (1987). But do they care about fairness? The dynamics of preferential treatment and minority interest. Basic and Applied Social Psychology, 8, 177-191.

Nieva, B., & Gutek, V. (1981). Women and work: A psychological perspective. New York: Praeger.

Read, P. B. (1974). Source of authority and the legitimation of leadership in small groups. Sociometry, 37, 189-204.

Schein, V. E. (1973). The relationship between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics. Journal of Applied Psychology, 57, 95-100.

Schein, V. E. (1975). Relationships between sex role stereotypes and requisite management characteristics among female managers. Journal of Applied Psychology, 60, 340-344.

Singer, M. E., & Singer, A. E. (1991). Justice in preferential hiring. Journal of Business Ethics, 10, 797-803

Stoppard, J. M., & Kalin, R. (1983). – 1224 Words | Term Paper ExampleGender typing and social desirability of personality in person evaluation. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 7, 209-218