An economy is said to be efficient when “there is no way to make some people better off without making others worse off” (GaddyEcon, 2006, p.87). However an efficient market is not necessarily fair to all. Due to this reason the government intervenes and imposes prices controls when “policy makers believe that the market price of a good or service is unfair to buyers or sellers” (Mankiw, 2009, p.113)

Price control according to GaddyEcon is a legal restriction on “how high or low, a market price may go” (2006 p.85). In the words of McTaggart et al. government intervention in the market may take the form of “price ceilings” and “price floors” (2007, p.791). A price ceiling is a “maximum price imposed by the government when it feels that the equilibrium price is too high” (Taylor and Weerapana, 2009. P.81). A price floor is a “regulation that makes it illegal to charge a price lower than a specified level” (McTaggart et al., 2007, p.791). This paper will concentrate on a type of price ceiling known as rent control and a type of price floor known as minimum wage.

Price Ceiling

Rent Ceiling: “rent ceiling” as McTaggart et al. explain, occurs when the government imposes rent control in the housing market (2007, p.137). Two excellent examples of rent controlled cities are; Prague and New York City.

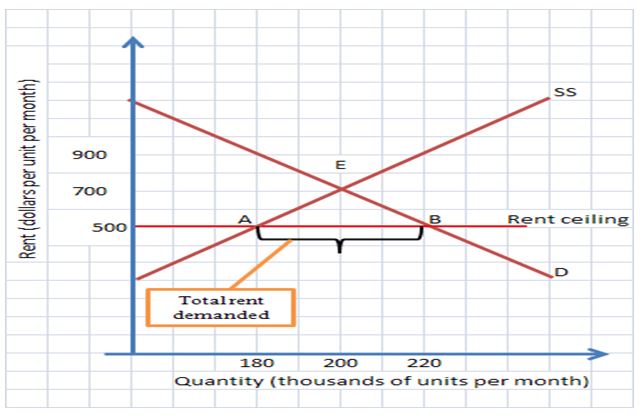

Take for example a hypothetical town called Deltaville that is situated in a flood prone region. Before the flood, the housing market was unregulated and the rent averaged $500. A freak flood washes off many housing units leaving many residents in dire need of accommodation. Figure 1 below shows Deltaville’s demand and supply for housing units. If left unregulated, the rent price would have stabilized at $700 per housing unit. However the state decides to impose a rent ceiling of “$500 a month – the rent before the flood” (McTaggart et al., 2007, p.131).

According to figure 1; the equilibrium price is $700. In the long run when more housing units are built, the rent may adjust down to $500. Left on its own, the Deltaville housing market will not be kind to some vulnerable families in the short run.

Deltaville not only has a real housing shortage (because 20,000 units were destroyed by the flood), an artificial demand of another 20,000 units is created by house seekers who “could not afford the higher market price [$700] but are prepared to buy at the lower official rate [$500]” (Mises, 1945, p.61).

Price control reduces the number of units supplied to 180,000 as shown in point A, and increases the quantity demanded to 220,000 (point B). This creates a shortage of 40,000 flats. The problem is that 40,000 families need shelter at the legal rent of $500 a month but can not get the units.

Note that initially Deltaville had 200,000 units that were fully occupied before the flood. 20,000 units were destroyed by the flood. If the government did not interfere, only 20,000 would be demanded. But now the town has only 180,000 units available that have somehow to be allocated to a demand of 220,000units. This inefficiency brings with it the following problems: search activity, a black market and inefficient allocation of resources as shown by Figure 2 below.

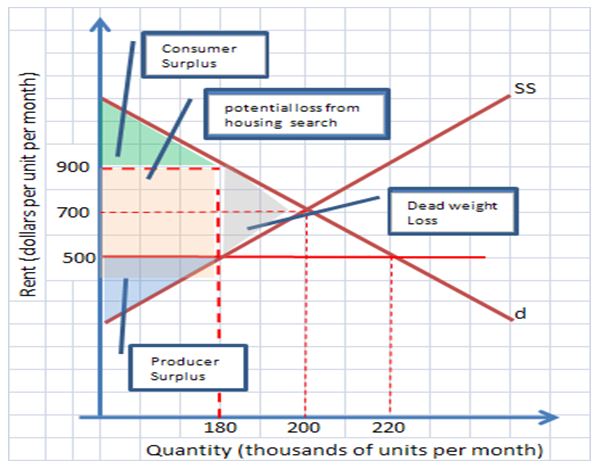

‘Search activity’ is “the time spent looking for someone with whom to do business” (McTaggart et al., 2007, p.132). When the government imposes a rent ceiling, the stakes of getting a house are raised and desperate house seekers have to spent long hours looking for a flat that has the right price. The time wasted in this effort could have been used in doing more productive things like working for extra income and spending quality time with the family.

A rent ceiling would lead to the mushrooming of a black market in the housing industry. As the graph shows, some tenants are willing to pay up to $900 for the 180,000th housing unit. Although it is illegal to rent a house at such an exorbitant price, landlords will be highly tempted to negotiate with willing desperate house seekers to pay an extra amount not reflected in the books. For example, if a house seeker is willing to part with $800 per month, it can be arranged that $500 is paid through the usual legal way, and $300 handed in cash to the landlord.

Price Floors

A price floor is an intervention by the government to push the market prices up. There are a number of sectors in the economy where the government can impose price floors. Price floors are imposed on the market for unskilled labor. Sharp price fluctuations in the agricultural industry “have a direct effect on the incomes of the producers and in all countries where peasants and farmers have influence this causes strong pressure [for the government to come up with] some species of price support scheme” (Nove, 2003, p.143)

The main reason why governments set a minimum wage is; as McTaggart et al. say “to provide families with a living wage and to ensure fair comparability among different occupations. [In addition], a minimum wage is intended to provide a safety net below which wages determined in decentralized bargains can not fall” (2007, p.137).

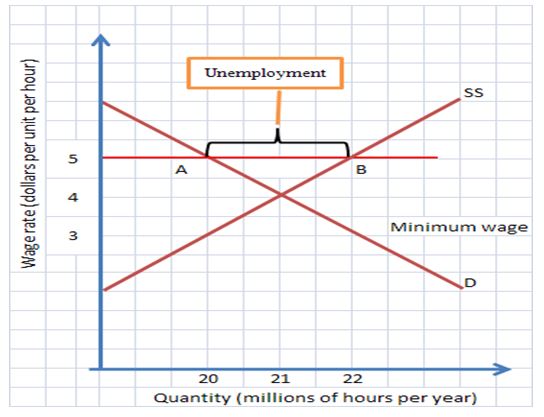

Figure 3 above below shows the minimum wage regulation made by a hypothetical government. The wage naturally determined by demand and supply of labor is $4 per hour. Thinking that it will improve matters economically for workers, the government sets the minimum wage floor at $5 per hour. This means that a wage below the $5 line is illegal.

Before the price floor a total of 21 million hours were being demanded and supplied. After the price floor, employers found it too costly to employ at such a high rate. The number of man hours demanded decreases to 20 million. The high wage rate on the other hand is an incentive for more workers to look for jobs. This increases the labor supplied to 22 million, point B. this situation creates unemployment amounting to 2 million hours which is the distance between A and B.

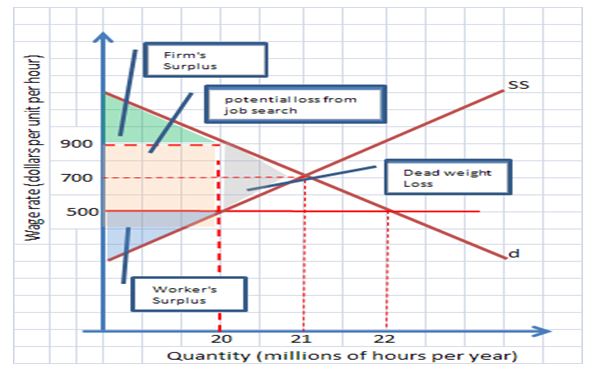

Figure 4 above explains the inefficiency occasioned by the imposition of a price floor. For example, a lot of job seekers will spend time and money looking for work as shown by the red box.

As McTaggart et al. explain “with only 20 million hours demanded, some workers are willing to supply that 20 millionth hour for $3. The firm’s surplus shrinks (blue triangle) as well as the worker’s surplus (green triangle). This creates a dead weight loss (grey triangle) which is a loss to the society. Unethical behavior like bribing to get a post, or working for less becomes rampant. The government should just have left the job market to self regulate.

Conclusion

Although the government may have noble intentions by trying to reign on the unstoppable forces of demand and supply they will always fail. Jones asserts that “a market distortion drives activity away from its socially efficient level” (2005) A price ceiling will bring about a shortage. A price floor will bring about a surplus. “There will always be a loss of total welfare resulting from price controls meaning that society as a whole is worse off than it would be without government intervention” (Welker, 2010).

As Kennedy recommends “control policies can be of benefit if they are complimented with appropriate monetary and fiscal policies” (n.d. p.219) However, since “in most of its forms, price control leads to consequences that are immediately bad and that can reasonably be comprehended,”(Pollard et al. ) policy makers should consider price regulations with a pinch of salt.

Works Cited

GraddyEcon, Price and Quality Controls, 2006. Web

Jones, Chris. Applied Welfare Economics, United Kingdom, Oxford University Press 2005, Print.

Kennedy Peter. Macroeconomic Essentials: Understanding Economics in the News. USA: The MIT Press, 2000. Print.

Mankiw, Gregory. Principles of Economics, USA: South-Western Cengage Learning Inc., 2009. Print.

McTaggart, Douglas, Christopher Findlay, and Michael Parkin, Economics. Australia: Pearson Education, 2007. Print.

Mises, V.L. The Omnipotent Government, USA: Yale University Press, 1945. Print.

Nove, A. Economics of Feasible Socialism. London, Great Britain: Routledge, 2003. Print.

Pollard, Stephen, Sean Gabb and Alberto Mingardi, The Human Cost of Pharmaceutical Price Controls in Europe. A Case for Reform, 2004. Web.

Taylor, John and Alkila Weerapana, Principles of Microeconomics, USA: Cengage Learning Inc. 2009. Print.

Welker, J. Price Controls and the Inefficiency of Government Intervention in the Free Market. 2010. Web.