Introduction

The use-value of a commodity is the utility of a product to the end-user. Any commodity should satisfy the consumer’s needs in order for it to have value. Once a commodity loses its value, the user will look for a substitute for the product. This means a consumer will value a commodity-based on the price they pay. However, every consumer is limited in income; therefore, he will be forced to make a choice among the many products that are available in the market. If a commodity in circulation has a useful value then the money value attached to it is very high as compared to other products (Altman, 45).

The use-value of a commodity

The circulation of commodities in the market is measured by the money value they generate because commodities are purchased and sold through money. Most people buy goods to sell and these goods should have some utility in order for them to be valued. The circulation of commodities helps in redistributing income and is based on the assumption of diminishing marginal utility. If a person’s income rises, the extra well-being derived from an additional dollar of income falls (Wilkinson, 251).

The circulation of commodities starts at the point of production where capital is used. A product is converted into money through selling. The capital which is money is invested and the product is produced. In this case, we can say the value of the product is in process and the value of the exchange is the value of the good that has been produced. This means that if capital is invested with the aim of producing a good for sale then the capital which is money at the same time a commodity will be preserved if the good produced is of the same magnitude as per the amount invested in that product (Mathew, 263)

For one thing, the total income of a factor depends on both its quantity and its marginal productivity; it is by no means easy to identify those changes in income which result from changes in its quantity and those which result from changes in marginal productivity. The theory assumes that all units of factors are homogeneous and are, therefore, capable of being measured; labor, for instance, could be measured in man-hours provided differences in grades and quality were ignored. However, ignoring differences between grades of labor is a serious oversight. The same goes for capital – the quantity of capital can be measured on the basis of what it costs at the time of purchase, but such costs have little bearing on the current value of the capital. Besides, it can be argued that although machines and equipment are productive, it does not follow that the owners of the capital are equally productive (Mathew, 364).

Consumer rationality is a general assumption in the economics of demand, and it is assumed that all behave in a way that will maximize their total utility. The consumer is rarely faced with absolute alternatives between different commodities and he is constantly trying to optimize the trade-off between satisfaction obtained from another. Choices in the real world are thus conditioned by marginal, and not total, utilities (Diamond, 79)

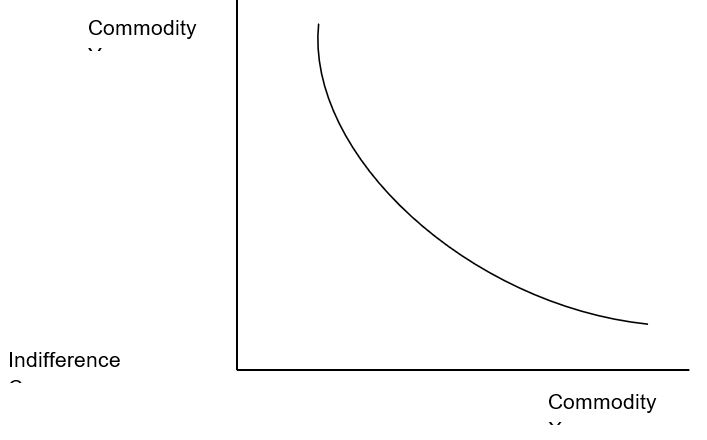

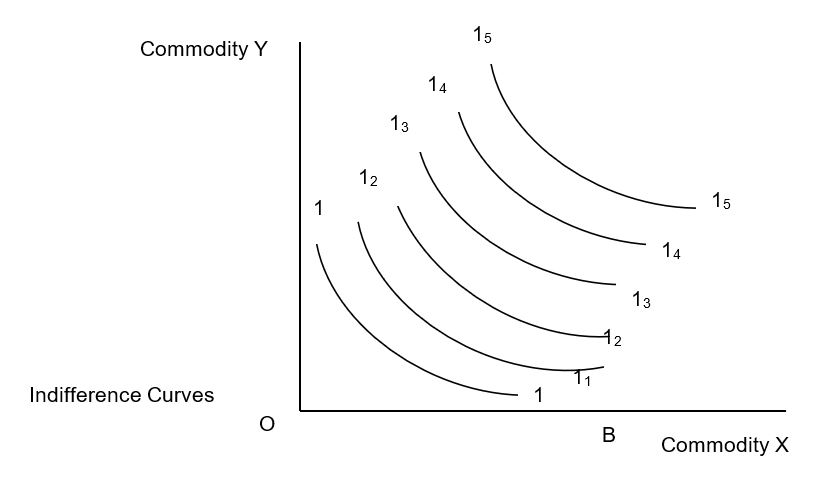

Consider a situation where there are only two goods available to a particular consumer and he has to decide the various combinations of consumption that give him equal satisfaction ignoring his income for the present we can construct a schedule and from that a curve, that shows the various combination of consumption that gives him equal satisfaction.

This is an indifference curve, and it illustrates the consumer’s indifference between the various combinations of commodities x and y. Thus, all points on this curve give the consumer the same satisfaction or equal total utility. All points to the right of this curve will give greater satisfaction than the present level since they will represent larger combinations of each commodity, while points to the left will give less satisfaction.

Note

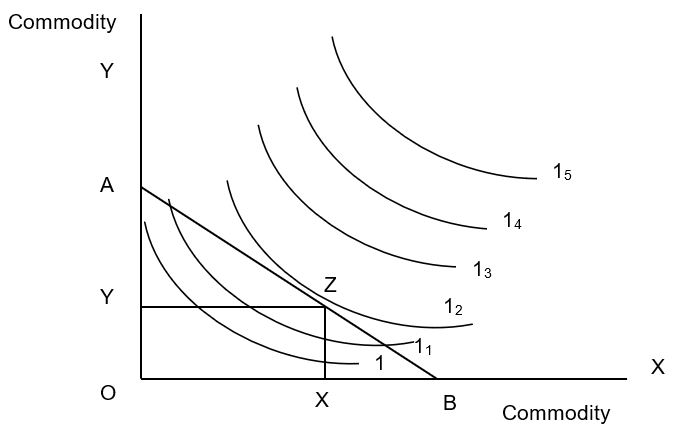

Indifference curves cannot intersect each other, since this would imply that two levels of satisfaction could be attained at the point of intersection. The next one may consider the consumer’s income. This is done by introducing the concept of the Budget Line, which is the line joining those combinations of the two commodities that would exhaust the consumer’s limited income (Sunstein, 198).

The curve which the budget line touches just one is the combination that gives the consumer maximum utility from his given income level. In the figure, this will occur at point Z, where the consumer buys ox units of commodity X and oy units of commodity Y.

Economics has argued that when technological changes occur in society, these changes can bring about alternations in the relative shares of land, labor and capital. For instance, Marx was one of the first economists to argue that labor-saving technology would lead to rising unemployment, a decline in the share of wages and conflict between labor and capital (Schwartz, 65).

Conclusion

Ignoring land to simplify the argument, neutral technical progress is that which leaves the ratio in which labor and capital are employed unchanged and so does not alter the wage-profit ratio. Non-neutral technical progress, on the other hand, takes the form of a new invention or the development of a new technique of production which is either labor-saving or capital-saving. It is often argued that labor-saving technical progress tends to lower the share of labor in the national income, whilst capital-saving technical progress tends to lower the share of capital (Mathew, 86).

Unfortunately, it is difficult in reality to distinguish changes in output that are due to changes in the capital-labor ratios brought about by technical progress from those which are due to increases in capital and labor. This is because in practice technical progress is inevitably associated with increases in the capital (Diamond, 126).

Works cited

Altman, Morris. Handbook of Contemporary Behavioral Economics: Foundations and Developments. New York: Sharpe, 2006.

Diamond, Peter. Behavioral Economics and its Applications. London: Princeton University Press, 2007.

Mathew, Rabin. Advances in Behavioral Economics. London: Princeton University Press, 2003.

Schwartz, Hugh. A Guide to Behavioral Economics. New York: Higher Education Publications.

Sunstein, Cass. Behavioral Law and Economics. London: Cambridge University Press, 2000.

Wilkinson, Nick. An Introduction to Behavioral Economics: A Guide for Students. Los Angeles: Palgrave Macmillan, 2007.