Background

Small and medium enterprises form the majority of businesses operating in the United Kingdom. They account for 99 percent of the enterprises found in all the major industries, including technology. The ventures are highly scalable. In addition, they are associated with high turnovers.

In this paper, the author sought to evaluate the profitability of SMEs in the UK’s technology industry. The performance of these entities was compared to that of large corporations operating in the same industry. In addition, the research sought to highlight the factors behind the differences in profitability between SMEs and corporations and how the identified problems can be addressed. The study assumed a critical literature review research design.

The findings of this study showed that the SMEs remain to be a sustainable source of employment, growth, and general excitement in the UK. However, their profitability is lower compared to that in the larger corporations. The discrepancies were attributed to the fact that SMEs have fewer employees. In addition, larger corporations have established roots in the market and have existed for many years in the industry.

As such, the large businesses have a competitive advantage over the small ventures. In spite of this, SMEs can catch up with the large corporations. They can achieve this through geographic expansion of operations, boosting their acquisition skills, and employing more professionals. In addition, they can tap into the financing schemes offered by the government.

Introduction

The UK is regarded as one of the best places in the world to start a business. To this end, it is ranked among the top 10 countries in the world with regards to favourable investment environment by the World Economic Forum and the World Bank (Young 2015). Like many parts of the world, majority of the businesses operating in the UK are categorised as small and medium sized (SMEs).

In the UK, SMEs are defined variously by different scholars depending on the context within which the term is used. For example, scholars in the tax sector have a specific definition of this form of business for the purposes of taxation. According to them, an entity with less than 500 workers should be regarded as a small and medium enterprise. In addition, for a business to be regarded as an SME, it must have an annual revenue turnover that is less than £100 million (Wright, Westhead & Ucbasaran 2007). Statisticians also adopt a unique definition for an SME. They regard it as a firm less than 250 members of staff (Acs, Szerb & Autio 2014).

An SME can also be conceptualised from an accounting perspective. To this end, it can be viewed as a firm with less than fifty employees. In addition, such an entity must have a turnover that is below £6.5 million. It is also worth mentioning that in some parts, the UK government utilises the definition of the European Union to categorise SMEs. To this end, union classifies a business into this cluster if it has less than 10 workers (National statistics 2015).

Based on these definitions, one can conclude that an SME is a business enterprise that employs between 0 and 250 persons. Furthermore, such a firm must have a turnover of between 6.5 and 50 million Pounds for it to be regarded as a small and medium sized undertaking. According to Oke, Burke, and Myers (2007), these businesses account for 99% of all the enterprises operating in the major industries in the global economy. In the UK alone, these enterprises employ more than 12 million persons (National statistics 2015).

According to Wolff and Pett (2006), SMEs are regarded as a major pillar of the UK economy. There is an increasing consensus that more support is needed to nurture and encourage small and medium businesses. There is further a general acceptance that SMEs account for the largest percentage of all businesses. Most of them have a considerable turnover of about 47 percent. However, the profit margins vary from one firm to the other.

The current research was conducted against this background of the significance of SMEs. The aim of this study is to compare the profit margins of SMEs and large corporations operating in the UK’s technology industry. To this end, the research will highlight the probable reasons behind the differences between the profitabilities of SMEs and corporations in this industry. Consequently, possible measures that can be put in place to address these differences and improve the standing of small and medium enterprises in the technology sector will be explored.

Statement of the Problem

There is a rising consensus that SMEs are the future ‘blue chip’ in the major industries found in the UK. However, in spite of the growth of these enterprises, challenges still exist with regards to the establishment of an enabling environment to support them (Guerrieri & Pietrobelli 2004). The profitability of these entities varies from one firm to the other and from one industry to the other. The variation is apparent in the UK’s technology industry.

As such, there is need for a critical analysis of the effectiveness of the SMEs in this sector in terms of profitability. Furthermore, the government and other stakeholders should come up with ways to improve the standing of SMEs in the technology sector.

Research Questions

The study sought to respond to these questions:

- Are SMEs more profitable than larger corporations in the UK’s technology industry?

- What is needed to establish a supportive environment for technological SMEs in the United Kingdom?

- How can the UK government, business and educational institutions, as well as other stakeholders do to build on existing strengths and improve the environment within which SMEs in the technology sector are operating within?

Research Objectives

The following were the objectives of the study:

- To evaluate the profitability of the SMEs and the larger corporations in the UK’s technology industry.

- Analyse the factors behind the variation in profits among SMEs and large corporations in the UK’s technology industry.

- Examine ways through which the environment within which technological SMEs in the UK are operating can be enhanced by different actors.

- Identify factors essential to the creation of a supportive environment for technological SMEs in the UK.

Research Hypothesis

The hypothesis postulated for the study, and which the researcher sought to test, was as follows:

Small and medium-sized enterprises in the UK’s technology sector record higher profits compared to the large corporations operating in the same industry.

Significance and Justification for the Study

The study provides an insight into the various factors that need to be addressed to enhance the performance of SMEs in the technology sector. In addition, the findings of the study will help stakeholders identify ways through which they can enhance the business environment for these SMEs in the United Kingdom. The research will also provide seminal information to address the question of whether or not SMEs are more effective compared to the larger corporations and firms in terms of profitability. The reasons behind performance disparities will be highlighted. Finally, the current study will act as a point of reference for other researchers conducting research in this field.

Research Method

The current study will assume a critical review of literature research design. To this end, the author will access secondary data regarding the profitability of SMEs and large corporations in the technology sector. Special focus will be given to those sources that provide information on the operation of these firms in the UK.

Theoretical Framework

There are several theories that can be used to explain the differences between the performance and profitability of SMEs and large corporations operating in the UK’s technology sector.

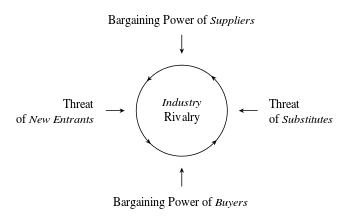

Porter’s five forces model

The theory can be used to analyse the operations of firms in the contemporary market. The profitability of SMEs in comparison to that of large firms in UK’s technology market can be viewed from the perspective of the differences between the levels of competitiveness in the two types of businesses (Carpenter & Petersen 2002).

According to Carpenter and Petersen (2002), the Porter’s theory is used to analyse the level of competition within a given sector. According to Porter (2008), there are five forces that impact on the nature of competition in an industry. On its part, competition determines the attractiveness, profitability, and performance of firms in the sector. An attractive industry is one that is characterised by high levels of profits for firms operating therein (Porter 2008). The figure below is a representation of the interplay between the five forces:

- Threat of new entrants. A profitable sector is likely to attract many investors. The existence of many players will, eventually, lead to increased competition (Carpenter & Petersen 2002). High competition will reduce the profitability and performance of firms in the sector. However, if existing firms are able to block the new entrants, this threat is reduced. It is a fact that the technology sector in the UK is profitable and attractive to new investors. However, most existing SMEs may be unable to block the entry of new players. But the established corporations may have a stranglehold on the industry, making it hard for new firms, such as SMEs, to enter the industry.

- Threat of substitutes. If customers have access to substitutes, the profitability of the firms in the industry may be reduced. However, there are no apparent substitutes to the products and services provided by technology SMEs and corporations in the UK. As such, the performance of these firms is not threatened (Porter 2008).

- The power of consumers. Consumers in the UK technology sector hold considerable power over the SMEs and corporations. The reason is that they can choose to buy from the various firms that operate in the sector (Porter 2008). As such, profitability for both SMEs and large firms is reduced.

- The power of suppliers. Suppliers in the UK’s technology sector have reduced strangle-hold over the firms (Carpenter & Petersen 2002). However, the large corporations can attract more suppliers than the SMEs given their capital outlay.

- Industry competitiveness. Competition is high in the UK’s technology sector. The reason is the high number of firms operating in the industry. However, large firms can weather the competition better than the SMEs (Porter 2008).

Non-price competition theory

According to Half (2014), SMEs in the UK can engage in non-price competition to deal with the threat posed by the large enterprises. To this end, they can differentiate their products by, among others, improving the quality and enhancing customer care services. The reason is that the SMEs, especially those operating in the technology sector, may find it hard to engage in price rivalry with the established firms.

As such, it may be hard and untenable for SMEs to reduce their prices and remain competitive. However, the large corporations can afford to engage in both non-price and price competition. Consequently, the performance and profitability of the small firms may be lower compared to that of the larger corporations (Half 2014).

Literature Review

The performance of SMEs and businesses in general can be said to be a complex and multifaceted construct. The complexity of this concept should be examined carefully by scholars and other analysts (Carpenter & Petersen 2002). The analysis of performance takes growth and profitability as the major dimensions of the construct. External factors also play a critical role in the performance of SMEs.

In their study, Wolff and Pett (2006) found out that internationalisation and innovation among SMEs have a positive impact and process improvements. On their part, external hostilities and product improvement will have a positive impact on the performance dimension (Dougal et al. 2012). Internationalisation should be based on seven major themes. The elements include timing, intensity, and sustainability.

To improve performance, SMEs seeking to internationalise their operations should also pay attention to the mode of expansion and impacts of the local environment on the venture (Ndubisi & Nwankwo 2013). Furthermore, the link between external resources and internationalisation should also be identified. Finally, it is important to critically review the effects of this form of expansion on the performance of the SME (Wright, Westhead & Ucbasaran 2007).

Product improvement is also associated with growth and profitability among SMEs (Ward & Rhodes 2014). However, studies conducted in this field reveal that process improvement does not have significant statistical impact on the growth and profitability of SMEs (Ward & Rhodes 2014). The growth of these firms is also theoretically affected by internal financial environment. Consequently, the performance of SMEs cannot be viewed from a single perspective.

The change in technology is affecting all industries in today’s economy. It calls for a paradigm shift in the industry. For instance, entities that were thriving within industrial zones should adjust their information linkages. They need to shift from a cluster-based perspective to a global and broader approach for them to cope (Guerrieri & Pietrobelli 2004).

There are various factors behind the success of SMEs operating in the globalised and high-tech industry. One of them is the dual evolution of local and foreign knowledge connections. The most important of these are the inter-firm and inter-institution links. The two are needed to provide local SMEs with the externalities required to cope with the problems of knowledge creation and internationalisation (Guerrieri & Pietrobelli 2004; Lu & Beamish 2001).

The distribution and performance of SMEs across sectors in the UK

According to McCloskey and Robertson (2009), SMEs account for over 99 percent of the overall population of businesses in most industries. By the end of 2016, it is estimated that the UK will have about 5.5 million business firms (Average profit made by small and medium enterprises n.d). About 96 percent of these will be micro businesses. The enterprises are expected to have an annula turnover of 19% (Half 2014). By early 2015, the number of SMEs operating in the country’s construction industry was below 20 percent. However, the figure was lower in the mining sector, where the firms accounted for 1 percent of all entities operating in the industry (Terrelonge 2015).

Figure 2 below is an illustration of the projected employment and turnover of all businesses in the UK by 2016:

From the figure above, it is clear that most of the businesses operating in the UK are small in size. Small enterprises account for about 99.3 percent of all firms in the country (National statistics 2015). Medium enterprises come second, with large firms coming last. However, the turnover from large firms was 53 percent. In contrast, SMEs account for roughly 47 percent of the turnover. The discrepancies are significant considering that SMEs employ about 60 percent of total population. With their huge turnover, large enterprises only employ about 40 percent of individuals in the UK (Perspectives on Britain’s fastest growing technology company 2013).

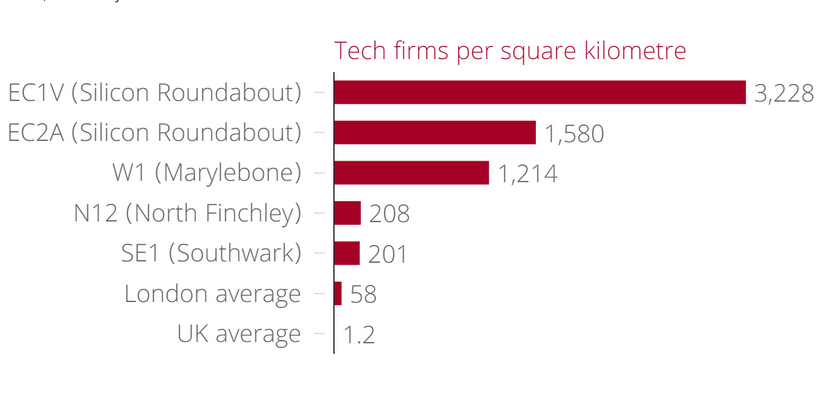

In the technology industry, about 20 percent of technology businesses in the UK are located in inner London (Small business 2013). The firms secured about 1.4 billion dollars in venture capital in 2014 (Half 2014). Figure 3 below is an illustration of the technology firms located in London:

The profitability of large enterprises and SMEs in the UK’s technology industry: A comparative analysis

The technology industry in the UK is characterised by major actors. Large businesses have established operations here. The entities record high turnovers compared to other businesses in the country. One of such company is the Acturis Group (Perspectives on Britain’s fastest-growing technology company 2013). The firm was established in 2000. It provides support services to the technology industry. It achieves this through the manufacture and distribution of technological innovations.

As of 2014, the company had about 12,000 customers. In addition, it has a turnover of over 29.6 million Pounds. Its growth as of 2014 was approximated to stand at 80 percent (Perspectives on Britain’s fastest-growing technology company 2013). The exemplary performance of this firm is attributed to professionalism, entrepreneurial culture, and years of established operations in the market (Terrelonge 2015).

On their part, the survival and performance of SMEs is largely anchored on the managerial approaches employed. Such strategies include a multi‐functional approach to decision making (Freel 2000). In addition, SMEs carry out market and competitor analysis with regards to product planning. The performance is further bolstered by effective communication of decisions and plans. As a result, the firms have a significant competitive advantage over their rivals in the corporate sector. However, this competitiveness is not always reflected in the profits recorded by these organisations (Dougal et al. 2012).

Most SMEs complain that the market is skewed in the favour of large enterprises (The Deloitte survey 2013). For example, they have few sources of start-up and operational capital compared to their larger counterparts. In addition, it is argued that the production and operation costs of small businesses are always higher (The Deloitted survey 2013). The educational system in the UK also appears to ignore the role played by SMEs in the economy. As such, most graduates lack enterpreneurial skills (Young 2015). The challenges make it hard for technology SMEs to reap the benefits that come with the industry. As such, their profitability remains low compared to that of large corporations operating in the same sector.

Methodology

The research utilised secondary data from journals, reports, and books from previous studies. The resources were accessed through the Google scholar engine and the university’s e-portal library. The following search terms and phrases were used:

- SMEs in the UK

- Technology industry in the UK

- Profitability of SMEs compared to larger corporations in technology industry in the UK

- Factors affecting the growth of SMEs in the UK

The search gave rise to 43 resources. However, inclusion and exclusion criteria were used to reduce the number to 24. The researcher focused on materials that were relevant to the topic, and which were published recently. Online from reputable entities, such as the UK government and major learning institutions were used. Articles from peer-reviewed journals were also used.

Data Management, Analysis, and Presentation

Thematic analysis was used to analyse the information and data from the sources. To this end, the researcher extracted data related to the identified themes from the selected resources.

A Comparison between the Profitability of SMEs and Large Corporations in the UK’s Technology Sector

It was found that the average profit margin of SMEs in the country’s technology sector rose from 8000 to 9000 British Pounds between 2014 and 2015 (Ward & Rhodes 2014). It was also noted that there is a positive correlation between the number of employees and profitability among these organisations. For example, the SMEs with zero employees reported average profits of 6000 and 7000 Pounds in 2014 and 2015 respectively (Young 2015). In contrast, those firms with between 1 and 9 employees registered 13000 and 14000 GBP in 2014 and 2015. The figure was even higher for firms with more than 250 employees.

Table 1: The link between number of employees and profitability.

The small enterprises also have a low turnover compared to the large and medium sized businesses. For example, the average turnover for small firms is less than 500,000 pounds. Medium-sized enterprises, on the other hand, have between 500,000 and 1 million Pounds in turnover. The figure is between 1 million and 10 million for the larger enterprises (Carpenter & Petersen 2002; Dougal et al. 2012).

The internet and software companies account for 59 percent of the revenue in the technology sector (London’s digital industry n.d). Their rate of growth rose from 811 to 1136 percent between 2014 and 2015 (National statistics 2015). The figures can be attributed to the scalable nature of these companies. The ‘harder’ technologies, which are relatively bigger, registered accounted for 10 percent of the total revenue in the technology industry (Mosey, Clare & Woodcock 2002). The revenue stood at 66 million pounds. Companies operating in the southern east part of the country recorded about 126 million Pounds in profits (Love & Irani 2004).

It is a fact that SMEs account for a large portion of companies operating in the UK. However, their turnover was about 19 percent. In constrast, larger firms had a turnover of 53 percent (Terrelonge 2015). The figures are for the year 2014. What this means is that the turnover of large corporations in the country’s technology sector was almost triple that of the SMEs. Consequently, one can conclude that larger firms still have an advantage over their smaller counterparts in terms of profitability.

The findings of studies conducted by other researchers regarding the performance and profitability of small firms in comparison to large corporations are largely unclear. The ambiguity is especially evident when profitability is considered as an operational factor. As such, the performance of small firms varies significantly from that of corporations in the same industry. The findings suggest that the nature of the returns associated with innovation may be partly dependent on the size of the firm (Johnson 2004).

Based on the findings made in this study, it is erroneous to conclude that SMEs in the technology sector have higher profit margins compared to the larger enterprises. The few cases of high profitability among SMEs in the technology sector can be attributed to their focus on incremental innovations. The innovations are positively related to the increase in sales turnover (Ndubisi & Nwankwo 2013).

The number of employees also plays a major factor in the profitability of a firm (Acs, Szerb & Autio 2014). To this end, firms with many employees are likely to perform better than those with fewer workers. Consequently, technology firms that are unable to support a large workforce are likely to perform poorly compared to corporations with many employees.

Factors Important to the Establishment of a Supportive Environment for Technology SMEs in the UK

A number of strategies can be put in place to improve the performance of SMEs operating in the UK’s technology sector. One of them is the issue of access to capital. According to Half (2014), these entities should be encouraged to acquire finance on their own. It is noted that finance is a major hindrance to their growth. Money is needed to attract customers and sustain growth. As such, it is important to assess the objectives of financial acquisition.

The current study identified an interesting perspective of the growth plans of most SMEs in the technology sector. To this end, the businesses focus on promoting their core products to new markets. Most of the companies are unable to sell multiple products to a few and selected customers. Consequently, the SMEs should raise capital to fund the development of new products for them to survive in the competitive market (Freel 2000). As a result, the firms will enhance their evolution. Consequently, they will increase their turnover and compete favourably with the large corporations.

It is also important for the SMES to increase the scope of their operations. In addition, they should strive to expand their geographical coverage. The strategy will help them acquire new customers and markets (The Deloitte survey 2013). Larger firms may have an advantage of established territorial boundaries. As such, their markets are largely assured. The case is different for SMEs, most of which start with numerous inherent challenges.

However, the geographical expansion should be undertaken cautiously. To this end, new destinations should be scrutinised and market accessibility assessed (The Deloitte survey 2013). The reason is that the major factor why SMEs find it hard to operate globally is lack of capacity and skills required to manage a worldwide customer base (Half 2014). However, if an SME is to realise a surge in product and service orders, it can employ more workers and acquire larger premises.

Promoting the Environment of SMEs: The Role of Stakeholders

Governments, educational institutions, and other businesses have a critical role to play in enhancing the business environment of SMEs. The aim is to help these firms achieve growth. It is a fact that most of these stakeholders have made efforts to support the growth of SMEs. For example, the UK government has provided an enabling environment by supporting SME start-ups and creating awareness among the public (McCloskey & Robertson 2009).

The corporate tax regime in the UK is lower than the prevailing figure in the developed world when it comes to technology SMEs. The move has made it possible for these firms to thrive in the country. Moreover, entrepreneurship has been made more attractive through the Entrepreneurship Investment Scheme and Seed Enterprise Investment Schemes (Young 2015). The two programs enhance capital support among SMEs. The apprenticeship Grant for Employers was also put in place to encourage the establishment of these entities. The grant provides £1,500 to start-ups in the technology sector.

So far, more than 80% of these grants have been given to firms employing 25 people or less. The aim is to help the firms train their future workforce (Young 2015). In addition, the government has reduced the cost of doing business in the country. All these are mechanisms that make it favorable for SMEs to take root in the industry. However, the government can do more by providing support to promote effective communication and advisory services to the technology SMEs.

According to Young (2015), SMEs can enhance their business environment by employing professionals. The experts will bring in the skills and knowledge required to make profits and identify viable investment opportunities. Furthermore, the businesses need to identify strategic locations and establish links with other firms operating in the sector. They should also reach out to students with varried skills in the education sector. The aim is to tap into the skills of the young minds.

Partnerships and trading can be used to promote the growth of technology SMEs. The reason is that these firms cannot grow in isolation. The governemnt has made it easier to recruit employees. For example, the authorities introduced an employment allowance of 2000 Pounds beginning in April 2014 (Half 2014). The move is significant given that most entities are operated by the owner. More than 70 percent of SMEs are run by their owners (Young 2015). Failure to recruit additional talent is a hindrance to the growth of SMEs. It limits the pool of skills available to the business. As such, the competitiveness of the firm is affected.

According to Johnson (2004), technology SMEs in the UK can respond to the challenges facing them by putting in place strategies aimed at promoting sustainable business operations. In addition, they should come up with ways to improve their revenue by expanding their operations and accessing more customers. They should understand that the creation of sustainable ventures is not a bad idea. However, they should note that lack of customers and reduced revenue will have a negative impact on the sustainability of the firm (Love & Irani 2004).

Conclusion and Recommendations

The current research examined the profitability and performance of SMEs operating in the UK’s technology industry. The performance was compared to that of large corporations in the same sector. It was found that the number of employees working for a given firm plays a significant role in the turnover and profitability of the business.

Consequently, since SMEs have fewer employees compared to the larger businesses, their turnover is relatively lower. It is also clear that SMEs operating in the country’s technology sector have sustained their growth in the market due to their scalable nature. However, the scalability does not necessarily lead to increase profits. As such, their performance is lower than that of macro businesses.

Several factors have been shown to hinder the profitability of technology SMEs. They include, among others, limited access to capital and the aggressiveness of the larger corporations. In addition, SMEs lack the skills required to operate in a competitive market. Furthermore, a limited operational scope in terms of geographical coverage has a negative impact on the profitability of the firms. Finally, SMEs are affected by the reduced development of new product lines.

The question that the dissertation aimed to answer was whether SMEs in the UK’s technology industry record higher profits than large firms. Based on the data analysed, it was found that their profitability is lower. However, most of them have sustained their growth over the years. The SMEs have lower turnovers compared to the macro businesses. It is only in rare cases where the small firms were found to achieve marginally higher profits.

In such cases, the development was attributed to incremental innovations. The innovations are normally a major focus of SME businesses. The setbacks associated with this reduced profitability were identified. In addition, the research provides recommendations on how the challenges can be addressed. It is noted that various stakeholders have a role to play in solving these problems.

It is noted that the UK economy is at the early stages of recovery. As such, it is too early to predict a boom in the performance of SMEs in the technology industry. However, it is noted that in spite of these setbacks, SMEs in the UK are growing at a fast pace. They will remain a major source of employment in the economy.

Recommendations

- The SMEs operating in the UK’s technology sector should enhance their access to finance and capital in general.

- The businesses should seek new markets by embracing geographical expansion.

- The firms should acquire a skilled labour force.

- The SMEs should be located strategically to optimise their access to markets.

- They should establish links and partnerships with other technology businesses.

- The firms should proactively seek financial subsidies provided by the UK government to help them compete with their larger counterparts.

If the SMEs in the UK’s technology sector maintain their current operational designs, their ability to compete with the larger firms and enhance their performance may not be actualised. If the above recommendations are implemented, the businesses can improve their standing in the global economy. Their profitability and competitiveness will be greatly enhanced. The SMEs can exploit the opportunities provided by the global markets to promote their growth.

References

Acs, Z, Szerb, L & Autio, E 2014, 2014 global enterpreneurship and development index, GEDI, Mason.

Average profit made by small and medium enterprises (SME) in the United Kingdom (UK) in the years ending June 2014 and June 2015, by enterprise size (in 1,000 GBP) n.d, Web.

Carpenter, R & Petersen, B 2002, ‘Is the growth of small firms constrained by internal finance?’, The Review of Economics and Statistics, vol. 84 no. 2, pp. 298-309.

Dougal, J, Fettiplace, S, York, C, Lambourne, E, Braidford, P & Stone, I 2012, Large businesses and SMEs: exploring how SMEs interact with large businesses, Web.

Freel, M 2000, ‘Do small innovating firms outperform non-innovators?’, Small Business Economics, vol. 14 no. 3, pp. 195-210.

Guerrieri, P & Pietrobelli, C 2004, ‘Industrial districts’ evolution and technological regimes: Italy and Taiwan’, Technovation, vol. 24 no. 11, pp. 899-914.

Half, R 2014, How can small businesses compete with large companies, Web.

Johnson, J 2004, ‘Factors influencing the early internationalisation of high technology start-ups: US and UK evidence’, Journal of International Entrepreneurship, vol. 2 no. 1, pp. 139-154.

London’s digital industry n.d, 2017, Web.

Love, P & Irani, Z 2004, ‘An exploratory study of information technology evaluation and benefits management practices of SMEs in the construction industry’, Information & Management, vol. 42 no. 1, pp. 227-242.

Lu, J & Beamish, P 2001, ‘The internationalisation and performance of SMEs’, Strategic Management Journal, vol. 22 no. 7, pp. 565-586.

McCloskey, M & Robertson, C 2009, Business statistics: a multimedia guide to concepts and applications, Wiley, London.

Mosey, S, Clare, J & Woodcock, D 2002, ‘Innovation decision making in British manufacturing SMEs’, Integrated Manufacturing Systems, vol. 13 no. 3, pp. 176-184.

National statistics: business population estimates 2015, Web.

Ndubisi, N & Nwankwo, S 2013, Enterprise development in SMEs and entrepreneurial firms: dynamic processes, IGI Global, New York.

Oke, A, Burke, G & Myers, A 2007, ‘Innovation types and performance in growing UK SMEs’, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, vol. 27 no. 7, pp. 735-753.

Perspectives on Britain’s fastest-growing technology company: innovation for growth 2013, Web.

Porter, M 2008, Competitive advantage: creating and sustaining superior performance, Free Press, New York.

Small business: GREAT ambition 2013, Web.

Terrelonge, Z 2015, The UK’s fastest growing private companies: hot 100 2015- (5) Acturis Group, Web.

The Deloitte survey: Q3 results- priority: expansion 2013, Web.

Ward, M & Rhodes, C 2014, Small businesses and the UK economy, Web.

Wolff, J & Pett, T 2006, ‘Small-firm performance: modeling the role of product and process improvements’, Journal of Small Business Management, vol. 44 no. 2, pp. 268-284.

Wright, M, Westhead, P & Ucbasaran, D 2007, ‘Internationalisation of small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs) and international entrepreneurship: a critique and policy implications, Regional Studies, vol. 41 no. 7, pp. 1013-1030.

Young, L 2015, The report on small firms: 2010-2015, Web.