Abstract

Change blindness refers to the inability of human beings to detect physical changes in their environment. Although different studies have established the concept, few have bothered to understand whether variations in change types affect the phenomenon. The aim of this paper is to find out whether change blindness varies with the type of change introduced. To test this phenomenon, three stimuli (incongruent, congruent and “within the category”) were introduced in an experiment that included 250 participants.

The independent variable was the type of change, and the dependent variable was the response to detecting the changes. The mean RT for “incongruent changes” was the highest, while “congruent changes” had the lowest mean. Broadly, it was established that change blindness varied with the type of change introduced because incongruent changes were the easiest to detect.

Introduction

Definition of Change Blindness

Change blindness refers to the inability of human beings to detect physical changes in their environment (Davies 2015). The concept is relevant to psychology because it is a measure of human limitations when using sight as a sensory stimulus (Briggs & Davies, 2015a). Several researchers have investigated this matter. Their findings appear below.

Key Research on Change Blindness

Many experiments conducted to test change blindness have been done by exposing human subjects to a flicker of images. For example, several studies have shown that some people fail to detect physical changes to an image when it flickers on and off (Briggs & Davies 2015a; Briggs & Davies 2015b). Relative to these investigations, Rensink and a group of other researchers have investigated the concept of change blindness through the flicker method and attention analysis and found that their respondents were unable to notice the differences between two paradigms after exposing them to variations in attention levels through the “attentional blink” framework (Briggs & Davies 2015a; Briggs &Davies 2015b).

O’Regan and his colleagues also conducted a similar study (the “mud splash” study), which established that “attentional blink” did not represent the overwriting of visual memory; instead, it meant that change blindness was in effect (Briggs & Davies 2015a; Briggs & Davies 2015b). O’Regan’s studies were similar to those of Rensink because they both proposed that central changes were more visible than marginal changes.

Simons and Levin’s “door study,” and Nisbett and Miyamoto’s research on change management also contributed to the same discussions through an analysis of the cultural environment and the review of contextual changes in human perception (Briggs & Davies 2015a; Briggs & Davies 2015b). The latter studies showed that the cultural environment had a significant impact on people’s change environment.

Simons and Levin’s study also highlighted the importance of paying attention to changes in the environment and their findings augur well with those of a similar report highlighted by Hagan (2015), which show that the main purpose of attention is to orient people to sensory stimuli. The findings also emphasise the importance of remaining in executive control and maintaining a strong sense of alertness to avoid change blindness. Although these studies largely draw attention to the main causes of change blindness, they fail to show whether different types of changes affect the same outcome.

Key Issue in Current Study

The aim of this paper is to find out whether to change blindness varied with the type of change introduced. To test this phenomenon, three different types of stimuli were introduced in an experiment. The first one was “within-category changes” where an item was replaced with another that belongs to the same category as the original one. The second one was “congruent change,” where the researcher replaced one object with another to match with the original scene, and the last one was the “incongruent change,” where one item was completely replaced with another that did not belong to the same scene or category. The independent variable was “type of change” and the dependent variable was “response time.”

Hypothesis

H1: Change blindness varies with the type of change introduced.

Method

Design

A within-participants experimental design was conducted to establish whether the type of change (independent variable) had an effect on the response time (dependent variable) the participants took to detect it. Therefore, all of the conditions of the independent variable measured involved the same group of participants. The order of the trials was randomised and the reaction times recorded to analyse the mean times for each stimulus introduced.

To make sure the participants were not biased or claimed to have noted nonexistent changes, an inbuilt control system was set up, where one-quarter of the images did not have any change attributed to them. Although the data relating to “no-change images” were not included in the study, they were used to identify unreliable information. Therefore, pieces of information relating to participants who consistently noted changes in the “no-change” category were eliminated from the study. This step ensured that the data included in the final report were accurate and reliable.

Participants

The study included data from 250 participants who were friends, colleagues or family members of the students who collected the research information (the respondents were all above 18 years). The students explained the research process to the participants before they chose to participate in it. Additionally, the participants took part in the research process voluntarily. In other words, the students did not coerce or pay them to do so. In this regard, they signed an informed consent form that stipulated the above provisions. The students also answered any lingering questions voiced by the respondents before the participants signed the informed consent form. This process happened both before and after the study.

Materials

As highlighted above, the main source of data for this study was the class-generated dataset for change blindness, which was developed through a series of experiments undertaken in 2017 by Open University students on their friends, family members and colleagues. The data were available in SPSS format within the Open University resource centre. This main source of information acted as the centre of empirical data. Secondary data were also used to complement the findings. Particularly, the class book titled “Investigating Psychology” provided a significant portion of the research materials used to complete this study.

The book’s chapters were reviewed to help the researcher make sense of the primary research findings. Similarly, the book was instrumental in explaining the significance of the study to the field of psychology. Key tenets of this analysis appear in the discussion section of this paper.

Two independently sourced peer-reviewed journals also formed part of the research materials used in this study. The journals helped the researcher to understand what experts in the field of psychology have written about change management and how their work could be instrumental in the completion of this research project. The keywords and phrases used to source these two journals were “change blindness” and “psychology.” Collectively, this research included a review of both primary and secondary data.

Procedure

The research experiment was designed to investigate change blindness using the flicker paradigm. The independent variable was “type of change” and the dependent variable was “response time.” Investigations were done by analysing the response time, which participants took to detect changes based on the type of change introduced. The participants viewed 16 everyday scenes. Each scene represented an experimental trial. In each trial, two almost identical images were displayed one after the other (an intervening blank screen was introduced to separate them).

The images were displayed for 0.25 seconds, and so was the blank screen. This sequence created a flicker. Only one change was made for every trial, but each type of change appeared four times. The participants were required to view the images and state whether they detected any change. If they noted one, they clicked on a mouse to indicate so. By doing this, a reaction time was recorded and analysed using the SPSS software version 23.

Results

A descriptive analysis method was carried out to investigate whether change blindness varied with the type of change introduced. In all the three categories of changes observed in the paper, there was a valid score for all the 250 participants. A deeper investigation of the findings showed that no data was eliminated because no respondent claimed there was a change on an image that had no such alteration. Comparatively, the mean score for “congruent changes,” “within-category changes,” and “incongruent changes” were 4.1, 5.0, and 5.1 respectively. This distribution in statistics shows that the mean RT for “incongruent changes” was the highest, while the “congruent changes” had the lowest mean.

This finding means that the respondents found it easier to detect congruent changes compared to “within the category” and “incongruent changes.” Conversely, the same outcome showed that incongruent changes were the hardest to detect because it took the respondents more time to do so. The modes for all the three types of changes investigated were within the range of 3.2 – 3.7. Appendix 1 highlights these findings. Broadly, this evidence supports the research hypothesis, which states that change blindness varies with the type of change introduced.

It is important to point out that the findings highlighted in this study are limited to the three types of stimuli (incongruent, congruent and “within the category”) mentioned in the introduction section. More importantly, they relate to the detection theory, which highlights how people detect information across different information-bearing patterns (Sammon & Bogue 2015). Its application to this theory is evident because it helps researchers to understand how people make decisions under conditions of uncertainty.

Discussion

According to the findings highlighted above, the mean RT for “incongruent changes” was the highest, while “congruent changes” had the lowest mean. This finding means that the respondents observed “congruent changes” more easily than the other two categories of changes investigated. Comparatively, it was harder for the respondents to notice incongruent changes. This finding is contrary to the views of other researchers, such as Toates (2015) (highlighted in the introduction), which suggested that incongruent changes would be easier to observe. “Within the category” changes were the second most easily observed category of variations among the group of respondents sampled.

This finding comes surprisingly because the respondents could have easily observed incongruent changes faster because they do not fit with the scene or category of the initial object. Watts and McDermott (2015) allude to this fact because they argue that it is easier for people to miss small details in flickering images. However, it is important to note that there were minimal differences in the mean of the reaction times recorded between the way the respondents reacted to “within-category changes” and “incongruent changes.” This finding could mean that the respondents almost evenly perceived both changes (Barrett & Kaye 2015).

The data analysed also showed that the most common response times were in the range of 3.5 – 3.7. This figure was true for all the three types of trials done. However, it is important to note that the congruent and incongruent changes had multiple modes. The smallest model for congruent changes was 3.59, while the smallest number of incongruent changes was 3.72. The modes highlighted above show that most of the respondents took about three seconds to detect changes in the items displayed in the experiment. A response time of three seconds shows that most of them were alert.

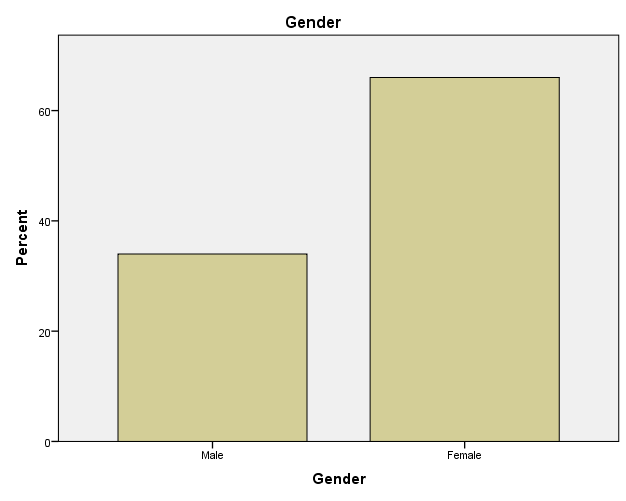

A demographic analysis of the findings also showed gender differences in how the respondents detected changes. For example, more females than men detected congruent changes, as shown in appendix 2. The above findings were also true for incongruent changes because there were more females than males who detected this type of change. However, a plausible explanation for this outcome could be that more females than male respondents took part in the study. Appendix 2 shows the distribution of gender percentages. Concisely, actual estimates of the analysis show that the total sample was 66% for women and 34% for men. An analysis of the respondents ‘ages shows that the most common age of the respondents was 29 years. However, the average age of the sample group (collectively) was 36 years.

The findings presented above are important to the field of psychology because understanding differences in change blindness could help to understand human cognitive processes better. Its importance in this field explains why this topic has captured the imagination of some researchers who have pointed out its relevance in measuring people’s attention (Davies 2015; Tree 2015; Lazard 2015).

Nonetheless, change blindness has a more profound influence on how we understand human perception, as is evident in the works of Kreitz et al. (2015). More importantly, it is applicable to certain fields of psychology, which strive to understand human perceptual factors beyond the purview of human consciousness. For example, Sammon and Bogue (2015) say it could help to explain why some people could track the movements of certain objects even without them consciously knowing they are doing so. In this regard, the findings of this paper could be applied in different disciplines beyond the context of psychology.

Lastly, future research should investigate the roles of the different types of stimuli in influencing human brain processes. In line with this conversation, the same future studies should help to understand the extent that the flicker paradigm influences internal representation.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Mean, Median and Modes.

Reference List

Barrett, J & Kaye, H 2015, ‘Can you do what I do? Learning: from conditioning to collaboration’, in R Capdevila, J Dixon & G Briggs (eds), Investigating psychology, 2nd edn, Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 155-171.

Briggs, G &Davies, S 2015a, ‘Is seeing believing?: visual perception and attention for dynamic scenes’, in R Capdevila, J Dixon & G Briggs (eds), Investigating psychology, 2nd edn, Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 111-152.

Briggs, G &Davies, S 2015b, ‘Can I do two things at once? Attention and dual tasking ability’, in R Capdevila, J Dixon & G Briggs (eds), Investigating psychology, 2nd edn, Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 77- 110.

Davies, S 2015, ‘Do you see what I see? The fundamentals of visual perception’, in R Capdevila, J Dixon & G Briggs (eds), Investigating psychology, 2nd edn, Milton Keynes: The Open University, 33-88.

Hagan, K 2015, ‘How do you feel about that? The psychology of attitudes’, in R Capdevila, J Dixon & G Briggs (eds), Investigating psychology, 2nd edn, Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 201-229.

Kreitz, C, Furley, P, Memmert, D & Simons, D 2015, ‘Inattentional blindness and individual differences in cognitive abilities’, PLoS ONE, vol. 10, no. 8, pp. 1-10.

Lazard, L 2015, ‘How do we make sense of the world? Categorisation and attribution’, in R Capdevila, J Dixon & G Briggs (eds), Investigating psychology, 2nd edn, Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 122-176.

Sammon, N & Bogue, J 2015, ‘The impact of attention on eyewitness identification and change blindness’, Journal of European Psychology Students, vol. 6, no. 2, pp.95–103.

Toates, F 2015, ‘Why do I feel this way? Brain, behaviour and mood’, in R Capdevila, J Dixon & G Briggs (eds), Investigating psychology, 2nd edn, Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 198-220.

Tree, J 2015, ‘How does my brain work? Neuroscience and plasticity’, in R Capdevila, J Dixon & G Briggs (eds), Investigating psychology, 2nd edn, Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 232-254.

Watts, S & McDermott, V 2015, ‘Why would I hang around with you? The psychology of personal relationships’, in R Capdevila, J Dixon & G Briggs (eds), Investigating psychology, 2nd edn, Milton Keynes: The Open University, pp. 167-198.