Introduction

In many ways, University presents a most vital rite of passage for the child metamorphosing to an adult. Intellectual challenge and growth are leagues beyond what is available at A-levels. College-age youth must master the difficult skills of self-directed study and pursuit of answers in a wide range of intellectual disciplines. For the first time, the student is fully aware that there are no pat answers, only plentiful theories and viewpoints on truth.

On the emotional side of things, youth in University may have already surmounted the obsessions and anxieties of pre-pubescence and early adolescence. However, the placid maturity of adulthood is still elusive. Away from home and, if not, permitted much more leeway by parents and guardians, older adolescents and youth confront new peer pressures to indulge in drink, smoking, illegal drugs and premarital sex. Consequently, there are more setbacks than hard-won achievements, emotional stress mounts higher, and students flail about unaided for coping strategies.

There is no lack of literature on adult emotional coping and the troublesome adjustments so characteristic of early adolescence. On the other hand, Watson (12-14) asserts, material about adolescent coping is relatively sparse (1).

Definitions

In principle, “emotional regulation” should be clear cut but definitions vary (Macklem 2) (2). Some regard emotion regulation as a trait that manifests from day to day; other theorists consign emotion regulation to a stage in personal development. For still other researchers, the ambiguity stems from the apparent difficulty of distinguishing emotion from emotional regulation.

Thus, emotion is commonly recognised as one category of affect, the term psychology applies to all non-rational and feeling states (Kring 22-40) (3). Beyond this point, any semblance of construct consensus vanishes. Izard (64), Walden and Smith (11-14) content themselves with describing emotions as anything palpable by the individual and, more often than not, validated by those observing the person (4, 5). Ledoux (56), Rottenberg and Gross (230) suggest that, at core, emotions merely respond to, and organize, everything in one’s surroundings (6, 7). The latter researchers add the dimension of adapting to potentially perilous or beneficial stimuli.

To Kagan (91), however, emotion is dynamic (8). There is always a precipitating event that provokes at least cognitive re-evaluation and some degree of physiological response; subjectively expressed feelings are altered and so is behaviour. Shweder (33) adds the dimension of having to recognise a state of heightened adrenalin as shock, fear or excitement, as the case may be (9). Finally, Ekman and Davidson (5) provide the insight that all emotions are subjective experiences that evoke memories (10).

By comparison, the concept of emotion regulation is far clearer, if still open to a wide variety of constructs. In Freudian psychoanalytic theory circa 1924, the ego and superego are the assembly of regulatory functions that keep the raw impulses of the id under control (Mitchell and Black, 31) (11). One throwback to this is the formulation of Cichetti, Akerman and Izard (5) that emotion regulation has to do with coordinating emotions and cognition (12). For the most part, however, contemporary researchers have been wont to measure emotion regulation in different ways.

Early in the 1990’s, for instance, Thompson (269-288) asserted his belief that regulation was inherent in all emotions because the latter consistently involved both the internal element of affect and extrinsic, behavioural manifestations. Central to this view is that a well-balanced person in homeostasis should be able to manage his emotions to some purposeful degree (13).

A decade later, Bridges, Margie and Zaff (6-39) put forward the construct of a group of processes that a person might use to call up a positive or negative emotion, hold onto the emotion, control or change it, and then differentiate between the feelings of emotion and how emotion might be displayed according to personal, social and environmental expectations (14). In a similar vein, Zeman, Cassano, and Perry-Parish (61) agree that emotion control requires ‘managing’ behavioural manifestations and social components but an individual in a state of homeostasis needs to reckon with ‘internal systems,’ too (15). Cichetti et al. (6) also argue for a very strong behavioural context: emotion regulation must not only prevent overt displays of negative emotions and maladaptive behaviour but also motivate, impel and organise adaptive (or ‘good’) behaviour (12).

More recently, Cole, Martin and Dennis (320-321)define emotion regulation as the changes, behaviourally observable or not, that are associated with emotions once they are triggered by some event or situation (16).

Elaborating on external triggers, there is the view of emotion regulation as object-or goal-oriented (Russell 165) (17). How an individual wants to present himself to others requires management of central affect, facial expressions and body language. Combining the idea of environmental stimuli and significant others, Garber, Braafladt and Weiss (99) suggest that opting to sustain or alter an emotional state is based on either a reflexive or reasoned interpersonal strategy. (18)

Whatever theoretical refinements are conceptualised, Hoeksma, Oosterlaan and Schipper (355) aver that there is no denying the goals of emotion regulation: a) alter or manage emotions according to personal goals; b) as the situation and contextual triggers direct; and, c) channelling frustration, anger and other emotional states towards preferred resolutions and post-conflict behaviour (19).

Students and Emotion Regulation

Emotion regulation is vital for optimal functioning of university students and guidance towards achieving this must take into account special circumstances of the college environment. In broad terms, the goal of attaining emotion regulation amongst students consists of:

Every child capable of developing a resilient mini-set of strategies…be able to deal more effectively with stress and pressure, to cope with everyday challenges, to bounce back from disappointments, adversity and trauma, to develop clear and realistic goals, to solve problems, to relate comfortably with others, and to treat oneself and others with respect. (Goldstein and Brooks 4) (20).

There is no question that a student’s emotional regulation is expected to advance and demonstrates age-appropriate competency even at college and university level (Cole et al. 1) (21). Macklem (10) attests that, early development aside, university students continue to refine emotion regulation via the context in which an emotion is felt and the unique culture that is university (22). Owing to the greater leeway for teaching approaches and idiosyncratic personalities in university campuses, students must adjust to those lecturers who tolerate intense emotion and others who prefer quiet students.

Nonetheless, some commonalities that provoke intensity of emotion – e.g. cheering in a sporting test – are carried over from earlier stages of academic schooling. University students are not spared from differential experiences owing to variable cognitive abilities, retained knowledge and maturity towards emotional regulation. As well, the same children who had problems in O and A levels are likely to go on being problematic youth in universities.

At university and beyond, research has amply shown that individuals are able to suppress or control their responses to different stimuli depending on culture, social context or emotional intelligence. They can consciously hold back or inhibit an unacceptable impulse, thought or feeling.

To accomplish control of their emotions, individuals deploy a wide range of strategies because, after all, “individuals influence which emotions they have, when they have them and how they experience and express them” (Gross 275) (23). Other researchers have confirmed that individuals differ systematically in their use of particular emotion regulation strategies and question if these differences have important implications for adaptation.

Living more independent lifestyles and yet far from mature, university students remain vulnerable to the interplay between strong emotion on one hand, and attention and behaviour on the other (Macklem 12) (22). But it is also true that emotion can provide the motivating impulse for studies (Cole et al. 329) (16). Some work hard not to fail and others avoid work to reduce anxiety.

Considering all these research-based learning, student services and others who have an influence on university students must in addition account for culture, assess the applicable measures of emotion regulation and plan appropriate interventions.

Among these three considerations, Eisenberg et al. insist that more research is needed for interventions that consider the increasingly heterogeneous nature of UK communities and academic institutions (256).

In general, practitioners aiming to help students, Macklem (9) proposes, would do well to design specific interventions for helping their wards plan and prioritise, learn to distance themselves from non-academic distractions and challenges, and reframe events and situations so as to gain new perspective on provocative situations that provoke their still-vulnerable ability at emotional control (24).

It is vital for student services staff to continue to gain insight into the relationship between emotional regulation and general adjustment of their university ‘clients’. “Healthy socialization, positive relationships with others and academic success” depend greatly on emotional regulation (Macklem 12) (2). The significance of training the students in emotional regulation cannot be stressed enough.

Measures of emotion regulation applicable to students need to be made available. Evidence based practices to strengthen emotion regulation must be studied further. More optimal strategies to help students build their ability at emotional regulation need to be identified. After all, guidance services see more of those students who are more vulnerable than their peers for being either highly dysregulated or burdened with a history of trauma. Whilst much research has been done in this field and good interventions are available even now, continuing training and refinements should generate better ideas and focus better on individual needs. Muraven and Baumeister find, for instance, how teaching students to keep to a regular regimen of exercise and relaxation substantially improves emotional regulation (255) (25).

It would be useful to study more about what students do for emotional regulation and how it affects their life stresses and academic performance. The objective is to help them learn that their emotions can be regulated and there are definite methods for achieving this. The information obtained may be imparted to their mentors in university, psychologists and all staff so that the students may be helped on occasions which call for them.

Methodology

Research Questions and Statement of Hypotheses

In general, the current study undertook to establish the existence of gender- ethnicity- and age-specific differences in the recognised antecedents of academic stress and the coping strategies that college students employ. University is potentially fertile ground to explore since students confront unremitting increases in workloads that logically enough lead to pronounced self-doubt about their aptitude for successful coping.

Accordingly, the key research questions are:

- Are sources of academic stress different for men and women, younger and older, white and non-white students?

- Do coping strategies vary markedly across all four defined student segments?

The corresponding null and alternative hypotheses to be tested are presented in the appropriate sections under section IV “Findings” below.

Research Design

The study is effectively a 6 x n design where n represents the number of coping strategies or types of stressors prevalent in college life:

Sampling Frame and Sampling Design

The sample consisted of 112 students recruited at random across various programmes and academic levels within Roehampton University. The actual distribution across gender, ages, and racial origins are shown in the “Sample Profile” section of “Findings” below.

Study Instruments

Since the literature has abundantly established that stress is a negative emotion strongly linked to doubt about coping and given the research questions that impel this study, two separate instruments were employed.

Gross & John’s Emotion Regulation Questionnaire (ERQ), a ten-item inventory meant to assess individual differences in the consistent use of two emotion regulation strategies: cognitive reappraisal and expressive suppression. “I control my feelings by changing the way I think about the situation I’m in” is one item that measures cognitive reappraisal. Suppression, on the other hand, is shown by items like, “I control my emotions by not expressing them.”

The ERQ is, in essence, about inner feelings and how individuals reveal or suppress their emotions. Each item was answerable on a Likert scale of 1 to 7, corresponding to “strongly disagree” to “strongly agree” (see Appendix A). The instrument consists of six reappraisal and four suppression items.

For four adult samples on which the ERQ was administered, the Cronbach alpha for internal consistency ranged from.75 to.82 (reappraisal items) and.68 to.75 (suppression items, Gross & John 359) (26).

Secondly, the Academic Stress Scale (Kohn & Frazer, 420) rates 34 different stressful situations (e.g., examinations, excessive homework, class speaking, crowded classrooms, learning new skills) on a 7-point scale ranging from 0 (not at all stressful) to 7 (extremely stressful), with an entry of 8 requested for situations that were not applicable to the individual (27). Scores are generated by taking the sum of the item ratings.

The Academic Stress Scale quantifies academic worry across three subscales: physical, psychological, and psychosocial. The physical stressors are environmental factors such as temperature, lighting, and noise. Secondly, the psychological stressors are in respect of non-rational reactions to events that have severe personal consequences (e.g., final grades, studying for an examination, and reading wrong material). Finally, the psychosocial stressors are those interpersonal interactions that impact the individual (e.g., class speaking, pop quizzes, and fast-paced lectures). Analysis can be further refined into three factors: environment (e.g., noisy classrooms), perception (e.g., unclear assignments), and demand (e.g., term papers).

The Academic Stress Scale has very good internal consistency, as measured by Cronbach’s alpha and split-half reliability (.92 and.86, respectively; Kohn & Frazer, 1986) (27). A copy of the ASQ is also attached in Appendix A.

Notwithstanding the fact that both instruments have been shown to have eminently satisfactory internal consistency, the author conducted a pilot test with 20 participants in late January. The results showed no substantive problems in either clarity or face validity.

Basic classifying information in respect of age, gender, and ethnicity was collected but neither names nor contact/identifying information were asked for so as to protect individual privacy.

Fieldwork

Fieldwork took place throughout February and March 2009, distant enough from final examinations that this source of life stress would not be unduly prominent.

On recruitment, participants were advised of the purpose behind the research and informed of their right to both withdraw at any time and not to answer questions that they feel uncomfortable with. Debrief and Consent Statements were distributed with a unique reference number. These forms are included in Appendix B.

Since the ERQ and ASQ are both self-administering forms, participants arriving at the study venue were handed their copies and permitted to accomplish these individually without proctoring over a period of approximately 40 minutes. On completion, participants left the accomplished forms, together with their signed consent statements, on a table at the front of the room. Subsequently, they took away a Debrief letter for future reference.

Data Analyses

Subsequent to data cleaning and removal of outliers, the first stage of data processing consisted of cross-tabulation of the independent variables (IV’s: age, gender, ethnicity) against the dependent variables (DV’s) of stressors and coping methods.

To this point, data analysis depended on frequency counts, modes, mean, median and variance since all the DV’s are ordinal data. Tests of significance followed. One can, a priori, choose α = 0.05 as the decision rule, meaning a 5% chance of being wrong when rejecting the null hypotheses. If any of the indicated statistical tests show the probability of occurrence of the observed result due to chance or sampling error at less than 5%, this gives us confidence for accepting the alternate hypotheses, chiefly that there is a difference in both stressors and coping strategies across the segments of students.

Given the categorical nature of the predictor variables gender, age and race, the specific tests done for significance of differences were Student’s t and the associated Levene’s validation test for variances.

Findings

Sample Profile

Table 1: Summary Statistics for Independent Variables.

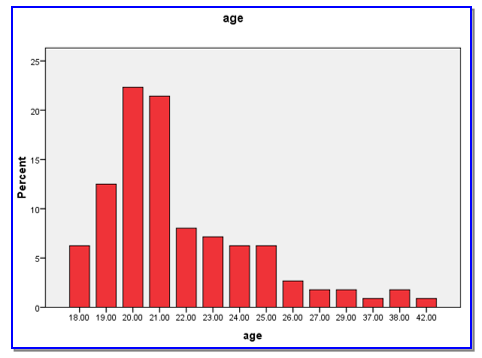

The 112 students ranged in age from 18 to 42 (see Table 1 alongside) with a skew toward the young (Figure 1 below). This skew explains why the median age of 21 years and the modal value of 20 years are both to the left of the mean at 22 years.

The standard deviation of the age distribution (Table 1) appears, at face value, to be wide at 4 years for ±1 SD from the mean. However, all this means is that random recruitment had produced a fairly dispersed age range of respondents. Nor is there anything unusual about the “long tail” of older students extending up to 42 years. In fact, this represents an undergraduate age profile younger than what might be expected for school populations that include postgraduate students.

Study participants exhibited a slight skew in favour of females (Table 2 below). This is not unusual at university level, as Manchester Metropolitan University reports for itself, neighbouring universities and the UK system of higher educational institutions in general (Figure 2 overleaf).

Table 2.

Table 3: Racial Diversity of Study Sample.

Absent hard data about the ethnic mix that prevails at Roehampton, one merely observes that those reporting themselves to be white comprised just under half the sample. Blacks constituted close to one-third and Asians were the third most numerous ethnic group. This is a distinctly more diverse racial mix compared to that for UK HEI’s generally (see Table 4 below).

Table 4.

Internal Consistency

The Roehampton sample yielded a Cronbach α of 0.91 for the Academic Stress Scale (Table 6 overleaf). This is very close to the 0.92 Kohn and Frazer found for the instrument after deploying the study instrument in 1985.

The low result on reliability for the ERQ as a whole (0.57, see Table 5) is explained by the fact that the instrument really assesses two different coping strategies. When the analysis is properly segregated into the component cognitive reappraisal and emotion suppression subscales (Tables 7 and 8), one finds eminently satisfactory Cronbach Alpha’s of 0.74 and 0.72, respectively. These compare very well with the internal consistency of 0.75 to 0.82 for reappraisal and 0.68 to 0.75 for suppression obtained by Gross and John (2003) with four samples of adults (26).

In sum, the Roehampton student sample demonstrated an internal reliability in addressing the scale items that is every bit as good as the original probative populations did. This suggests that the students took the test rationale and administration seriously, thereby removing a potential source of error.

Table 5: Reliability Statistics for the ERQ

Table 6: Reliability Statistics for the Academic Stress Scale

Table 7: Internal Reliability – ERQ Cognitive Reappraisal Subscale

Table 8: Internal Reliability — ERQ Emotion Suppression Subscale

The Emotion Regulation Questionnaire

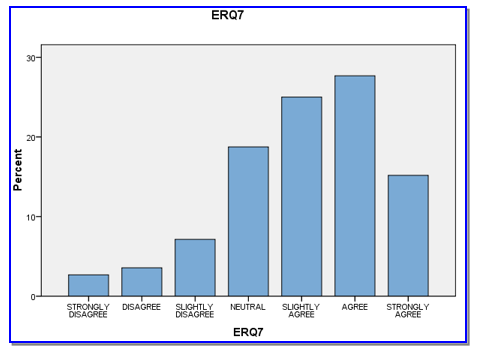

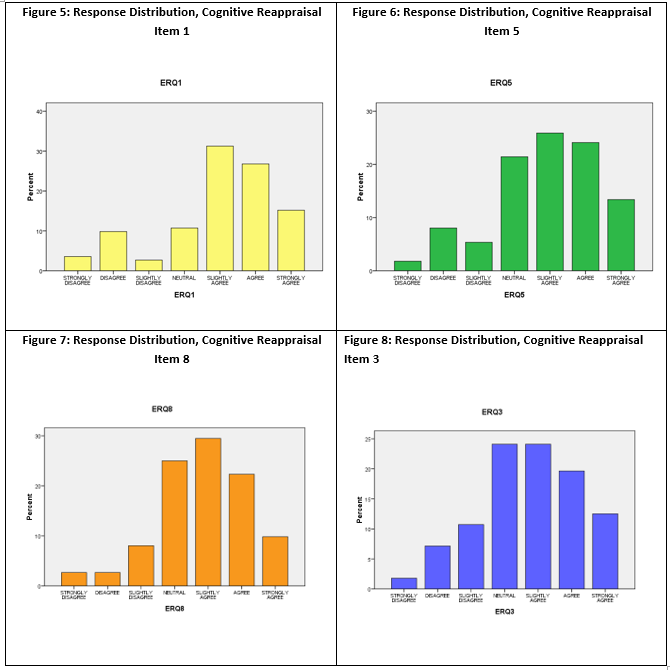

Figure 3 (overleaf) shows that the students as a group were most inclined to agree with the cognitive reappraisal items 7, 5, 1, 8 and 3. This means they put a premium on re-thinking their options rather than rely on suppressing strong emotion.

Specifically, students agreed most with the statement, ‘When I want to feel more positive emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation.’ On the other hand, the item mean rating of 5.04 corresponds to tentative agreement on the seven-point scale where 4.0 is neutral. Examining the response breakdown, one sees that more often than not (around 40%), students were inclined to say they either ‘agreed’ or ‘strongly agreed’ in principle with cognitive reappraisal as a way of coping with a disagreeable situation.

Evidently, the average is pulled downward by a relatively few who ‘disagree’ or ‘strongly disagree’. The impression of dispersion is reinforced by a standard deviation of 1.4 (Table 9 below)

Table 9: ERQ, the Reappraisal Items.

In order of agreement, the secondary emotion coping strategies of students revolve on cognitive reappraisal items:

- 1 ‘When I want to feel more positive emotion (such as joy or amusement), I change what I’m thinking about.

- 5 ‘When I’m faced with a stressful situation, I make myself think about it in a way that helps me stay calm.’

- 8 ‘I control my emotions by changing the way I think about the situation I’m in.

- 3 ‘When I want to feel less negative emotion (such as sadness or anger), I change what I’m thinking about.’

For the most part, the shape of the response distributions for these top-ranking ERQ items resemble those for ERQ 7 (see Figures 5-8) except that the response pattern for ERQ3 presents as a more tentative sort of agreement.

Proceeding to the research questions, the applicable null and alternative hypotheses are as follows:

- H01: There is no difference in stress coping between younger and older students.

- Ha1 : There is a difference in stress coping between younger and older students.

- H02 : There is no difference in stress coping between male and female students.

- Ha2 : There is a difference in stress coping between male and female students.

- H03 : There is no difference in stress coping strategies between white and non-white students.

- Ha3 : There is a difference in stress coping between white and non-white students.

Since gender, ethnicity and age class are categorical variables, we rely on the independent samples t-test to assess for statistical significance.

On age as the predictor variable, we assess, first of all, the magnitude of the mean scale ratings across the age groups. Table 10 (overleaf) shows that three items stand out. Older students were more likely to agree with the cognitive reappraisal items ERQ 7 and 10 while younger students were somewhat more likely to agree with the emotion suppression item ERQ4.

Employing the t test to see if the magnitudes shown in table 10 are so close as to be random variation or significant in statistical terms, we assess first of all the results for Levene’s test of equality of variances (Table 11 in page 25). A fairly low F value for Levene’s Test (e.g. 5.5 for ERQ1 or less) and a test for significance that exceeds p = 0.05 confirms that the variances in the data are homogenous and that one basic assumption of the t test therefore holds. Hence, one scrutinizes the row for “Equal variances assumed” for items ERQ 1, 3, 4, 5 to 8 and 10, those that meet this standard. On this basis, only one of the eight items, ERQ7, obtains a t value that is barely high enough to meet the p = 0.05 cut-off.

Table 10: Differential Response to Coping Strategies by Age Group.

For the two other items where equal variances cannot be assumed, ERQ10 exhibits a t value of -2.01 with an associated significance statistic s = 0.05.

The difference in mean ratings for ERQ7 and ERQ10 is of such magnitude that it could have occurred purely by chance less than five times in a hundred re-sampling passes. Hence, one rejects the null hypothesis, accepts the alternate and concludes that older students are more likely to adopt the reappraisal coping strategy embodied in the scale items:

ERQ7 – When I want to feel more positive emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation.

ERQ10 – When I want to feel less negative emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation.

Table 11: results of t Test for All ERQ Items, by Age Groups.

Turning to gender as the second predictor variable, we see from Table 12 (overleaf) that the results are mixed. The differences for most of the mean ratings across gender are too close to call, with men apparently more empathic than women when it came to the emotion suppression items ERQ 2 and 6.

Nine of ten ERQ items (except ERQ4) pass Levene’s test for equality of variances (Table 13 in page 27). Regardless of which variance assumption prevails, however, none of the t values were high enough to meet the p = 0.05 cut-off.

We perforce accept the null hypothesis and conclude that there are no statistically significant differences in male and female coping strategies.

Table 12: Differential Response to Coping Strategies by Gender.

Table 13: Emotion Coping Strategies by Gender.

In respect of the third predictor variable, ethnicity, results are similarly inconclusive. Levene’s test for equality of variances is met across all ten emotion coping strategy items (see Table 14 overleaf). However, none of the apparent gaps (Table 1, see Appendix C) between the scale means of whites on one hand and Asians, Blacks and mixed-race students, on the other hand, are statistically significant. Hence, we accept the null hypothesis and conclude that ethnicity makes no difference in emotion control strategies.

Table 14: Emotion Coping Strategies by Gender.

Academic Stress Questionnaire

Across all 34 items in the ASQ, the relatively more stressful sources of worry are revealed by high mean ratings of 5 and up (on an eight-point scale where 0 = ‘no stress’ and 7 = ‘extreme stress’, see Figure 9 overleaf) on these ten items:

- H04 : There is no difference in academic stressors between male and female students.

- Ha4 : There is a difference in academic stressors between male and female students.

On gender as the first predictor variable, Levene’s test of equality of variances (Table 15 in page 32 ) admits all but one of the 34 ASQ items. Hence, one scrutinizes the row for ‘Equal variances assumed’ for 33 items and ‘Unequal variances assumed’ for the sole exception. On this basis, items 16, 17 and 30 obtain t values that are high enough to meet the p = 0.05 cut-off. For the only item where equal variances cannot be assumed, ASQ33 exhibits such a low t value (-0.9) that random variation may well account for the difference across genders.

The difference in mean ratings for the three items in question is of such magnitude that they could have occurred purely by chance less than thrice in a hundred re-sampling passes. Hence, one rejects the null hypothesis, accepts the alternate and, by reference to Table 2 (Appendix C), concludes that female students are more likely to be worried by finances, psychosocial problems, and external pressures to do well embodied in the scale items:

- 16. Need to do well (imposed by others)

- 17. Interpersonal difficulties

- 30. Financial problems

Table 15: Results of t Test for Academic Stressors by Gender.

- H02 : There is no difference in academic stressors between younger (18 to 21 years old) and older (22 to 42 years old) students.

- Ha2 : There is a difference in academic stressors between younger and older students.

For the second predictor variable, age group, 31 of 34 items hurdled Levene’s test for equality of variances (Table 16 in page 35 ). In fact, the only item in the whole scale that met the significance statistic s < 0.05 also qualified under the t test assumption of data being homogenous:

ASQ32, the Physiological item ‘Personal health problems’ returned a t value of such size (-2.381) as to relegate random chance to less than twice (p = 0.019) in a hundred re-surveys. Given the direction of the difference revealed in Table 17 (below), we reject the null hypothesis, accept the alternate and conclude that health concerns are the only distinction between older and younger students.

Table 16: Results of t Test for Age Group.

- H03 : There is no difference in academic stressors between white and non-white students.

- Ha3 : There is a difference in academic stressors between white and non-white students.

In the analysis of ethnicity as the final predictor variable, all 34 items met the t test assumption of data homogeneity in point of Levene’s test (Table 17 in page 39). As it turned out, five sources of worry served to differentiate whites and non-whites:

Since the magnitude of the differences between the two racial categories are such as to consign chance occurrence to at most four times in a hundred re-surveys, we reject the null hypothesis, accepts the alternate and conclude that:

- Native/White students worry more than those of other races about the volume of material their courses cover.

- On the other hand, those of Caribbean, African or Asian extraction are under more pressure from psychosocial, academic demand, financial matters, and perceptions that their curricula are extraordinarily dull.

Table 17: Results of t Test for Ethnicity.

Discussion

University is, for the most part, a supremely enriching and memorable stage in life but, Dyson and Renk (2006, 1233) point out, newly-freed youth frequently confront tremendous anxiety and stress for (28). On top of the overriding concern about meeting their marks-centred expectations and those of their parents (Blimling and Miltenberger 105-110) college-age students face multiple stressors(29). Peer pressure remains strong but new stressors include choosing a major that is intrinsic to their future plans, demonstrating competence in examinations and coursework, meeting the challenges posed by demanding tutors, and successfully making the transition to the financial and emotional independence that are hallmarks of adulthood. All these comprise emotionally taxing experiences for many university students.

It is to be expected, therefore, that persistent experiences with stress and anxiety impinge on the total functioning of the individual and on academic performance, naturally enough (Silva, Dorso, Azhar, & Renk, 2007, 154) (30).

The findings of this study are of necessity viewed within the context of emotional expression and coping as the criterion variables. Emotions arise when university students confront situations that, as Lang, Bradley, and Cuthbert (401) put it, have affective properties and put these youthful individuals under emotional stress (31).

Quite naturally, the prominent emotion-arousing pressures university students experience can be categorised under psychological (or internally-felt) stress, perception and academic demand.

In the first category are the psychological stresses students experience when preparing and sitting for examinations, foreboding about how well they did, tension because they ‘forgot’ all about an assignment,

In turn, psychological pressures of the type brought on by perception comprise pondering how to proceed with an assignment the scope of which is unclear or, having made an effort to produce an assessment project, uncertainty whether they have done right by tutor’s instructions. Also featuring rather prominently in the psychological-perception continuum was worry caused by what appeared to be unclear course objectives. This may link to difficulties with the course and be associated with poor value perception, such as when a university student believes that a course has no relevance to his personal growth or career prospects.

Yet the third class of sources of stress are psychological-demand, referring to quantity or volume of work and the quality that they must strive for. Specifically, youth at Roehampton worry about the amount of academic work they must do (presumably because they have put these off till late in the term). Hence, they complain about not having enough time to study, about coursework deadlines coming too close together for comfort. Psychological-demand pressures can also be self-generated, as when students drive themselves to consistently high achievement. And as is true for most, even university graduates, needing to craft an essay or compile an assessment project inspires sheer terror about having to arrive at the right synthesis of ideas and needing to express themselves according to the standards they see in course materials and textbooks.

If all the above seems the all-too-familiar litany of emotional hazards underachieving students are prone to, it bears pointing out that problems with peer pressure, interpersonal conflict, sexuality, loneliness, and homesickness rank very low in the acknowledged hierarchy of school-setting stresses. Roehampton students are also unlikely to count conflict with lecturers as a source of emotional stress nor rationalise this as an excuse for poor academic achievement

This study goes beyond identifying sources of academic stress to demonstrate at least one facet by which emotional response relates to inaction or behavioural outcomes. In doing so, the study abides by such work as Scherer’s (1999, 640) who demonstrated that the attitude to, and assessment of, the affective properties of emotion propels changes in the impulse to individual action and the probability of different behaviours given the environmental context.

Measuring the ‘impulse’ to either cognitive reappraisal or emotion suppression, as the ERQ facilitates, is consistent with the findings of Cacioppo and Gardner (1999) about emotion bringing about multidimensional change in cognitive, social and physiological activity (32). Beyond emotional response, one takes cognizance of findings that the impact of emotions also extend to motivation and the ability, real or perceived, to actually perform (Bandura, 1997) according to the expectations and standards prevalent in academic life (33). In short, how one handles emotion has consequences for output in the university setting.

Not to be overlooked, however, is the aspect of emotion detracting from productive action. Some emotions do facilitate effective functioning but the physical and social circumstances can also stimulate affective reactions that conflict with the goals and well-being of students. Sustained stress, for instance, is characterised by long-lasting negative emotions that impact adversely on health (Suinn, 2001) (34), interpersonal relations, and classroom learning and productive output (Compas, Connor-Smith, Saltzman, Harding Thomsen, and Wadsworth 88-91; Gallo & Matthews 12-13) (35, 36). So it may well be that students experience a vicious cycle of negative emotional response. They recognise that interpersonal relations and classroom standards are sources of stress; repression or otherwise managing emotional outbursts in maladjusted fashion in turn damages their ability to handle interpersonal relations and classroom pressures well.

In fact, this study found that students as a group were overtly in favour of cognitive reappraisal (items 7, 5, 1, 8 and 3 in the ERQ) rather than suppression as a way of coping with strong emotion.

Age appears to correlate substantively with the belief in cognitive reappraisal. Specifically, older students are more likely to adopt the reappraisal coping strategy embodied in the scale items:

- ERQ7 – When I want to feel more positive emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation.

- ERQ10 – When I want to feel less negative emotion, I change the way I’m thinking about the situation.

The implication is that putting a value on cognitive reappraisal is a function of the greater maturity of outlook that comes with age. But if this relationship is logical and consistent, why were the findings not statistically significant for all five cognitive reappraisal items?

Frazier (13) suggests, in fact, that the body of literature is equivocal about the extent to which age is an influential factor on cognitive reappraisal coping (37). Researchers seem to agree, however, that emotional development and key life experiences may be the true antecedents of affect regulation processes in general and coping by reappraisal in particular. Seeking to validate the prevalence of the twin coping strategies that are also the subject of the present study, Frazier investigated the effects of cognitive reappraisal and response modulation on subjective and physiological responses in respect of films that were variously pleasant or aroused strong emotion.

Subsequent to experimental treatment in the course of which they were assigned to deliberate reappraisal or emotion suppression conditions, the researcher found that age made no difference in response measures to stimulus valence and arousal. However, older adults who employed cognitive reappraisal evinced lower physiological response and arousal (as measured physiologically by skin conductance response) than younger adults did during exposure to films with pronounced negative themes. On the whole, it does seem there is little reason to expect pronounced differences in emotion control strategies by age.

Across the gender divide, the evidence seems mixed. There should be differences in emotional response. One indicator is the finding form this study that female students are more likely to be worried by finances, psychosocial problems, and external pressures to do well. These stress sources are embodied in the scale items:

- 16. Need to do well (externally imposed)

- 17. Interpersonal difficulties

- 30. Financial problems

If numerous book and article authors consistently find that men and women differ in their emotional stressors and coping strategies (Gray 48) (38), as well as disorders revolving on emotional dysfunction (Gater et al. 410-411) (39), why then did this study reveal no stressors on which males felt more worried? Why does the ERQ reveal no essential differences by gender?

The answer may well lie in the fact that the ERQ is comparatively blunt, subject to all the limitations of paper-and-pencil study instruments. A recent effort by McRae, Ochsner, Mauss, Gabrieli and Gross (144) reached much the same conclusion when men and women were exposed to negatively-valenced pictures and with prior instructions to modulate their responses with cognitive reappraisal (40). Behavioural and observed indicators revealed no large differences in the way males and females evinced control over negative emotion.

But the team had also prepared a physiological-neural measure and true enough, functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) revealed gender differences in neural activity while exposed to the disturbing pictures. Despite ERQ answers to the contrary, males evinced lower gains in prefrontal regions of the brain strongly associated with reappraisal. Activity in the amygdala, linked with emotional responding, also rose markedly. To the team, such a result was open to two non-conflicting interpretations. Males may be able to call automatic emotion regulation and therefore require less effort to utilize cognitive regulation. A second possibility was that females may be better able to call on positive emotions to trigger reappraisal of negative emotions.

Replication of this experimental effort at neural assessment is obviously called for. Meantime, the findings of the research team imply that future analysis of gender differences in emotional control had best account for both emotional reactivity and regulation.

As to the other hypotheses this study pursued about differences by age and ethnicity, it turned out that:

- ASQ32, the Physiological item ‘Personal health problems’ returned a t value of such size (-2.381) as to relegate random chance to less than twice (p = 0.019) in a hundred re-surveys. Given the direction of the difference, we accept the alternate hypothesis and conclude that health concerns are the only distinction between older and younger students. This is perhaps to be expected since the presence of a few middle-aged outliers in the sample could have contributed to inflated concerns about the onset of degenerative syndromes.

- Native/White students worry more than those of other races about the volume of material their courses cover.

- On the other hand, those of Caribbean, African or Asian extraction are under more pressure from psychosocial, academic demand, financial matters, and perceptions that their curricula are extraordinarily dull. This implies that greater diversity on campus requires of guidance and student services increased proactive attention to the disadvantages, real or perceived, of minority students. Clearly, the social and political imperative for assimilation of the foreign-born and those born of minority races in the UK applies as much in university as it does in surrounding residential communities.

Conclusion

This study has established that Roehampton students avow a preference for cognitive reappraisal rather than rely on suppressing strong emotion. Considering many are struggling to maturity still, reappraisal may be more aspirational and attitudinal rather than a coping strategy they are able to easily summon from day to day. Nonetheless, emotion control by reappraisal is at least a rationally desirable good that mentors and guidance services may leverage as a starting point when endeavouring to see students through inevitable crises. The younger the student, the lower perhaps the value given to cognitive reappraisal. On the other hand, student services may reliably count on reappraisal apply equally across gender and racial divides.

There is certainly no lack of stressors in university life. The results of this study suggest that the more prevalent sources of worry naturally have to do with psychological worry about academic demands. Also at the forefront are stressors brought about by perceptual gaps in respect of assignment details and course objectives, usually because clarity has come a little late in the term.

The variety of stressors covered by the Academic Stress Questionnaire largely affirms what student guidance services have long realised: university students present with idiosyncratic complexes of inadequacies, worries and lapses. Hence, knowing in advance that academically-oriented psychological worries are more prevalent helps student services act proactively in respect of orientation kits and other preparations students should receive on entrance to university.

At the end of the day, individual and psychosocial commonalities help explain why female students are more likely to be worried by finances, psychosocial problems, and external pressures to do well (rather than the self-imposed drive to excellence that ranks ahead for the rest of the population. Tutors would also do well to be aware of racial differences where native Anglos worry more than those other races do about the volume of material their courses cover; those of Caribbean, African or Asian extraction, on the other hand, are under more pressure from psychosocial, academic demand, financial matters, and perceptions that their curricula are extraordinarily dull.

In future, there is surely scope for incorporating the ERQ in baseline capacity and maturity measures for incoming freshmen. Employing this and the ASQ in periodic benchmark assessments, together with suitable anxiety and depression instruments, will surely go a long way toward validating the benefit from peer-aided, crisis or other forms of intervention.

Works Cited

Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York: W.H. Freeman and Company.

Beauregard, M., Lévesque, J., and Paquette, V. (2004). “Neural basis of conscious and voluntary self-regulation of emotion”. In M. Beauregard (Ed.), Consciousness, Emotional Self- Regulation and the Brain (pp. 163–194). Philadelphia: John Benjamins Publishing Company.

Behncke, L. (2002). Self-regulation: A brief review. Athletic Insight: The Online Journal of Sport Psychology, 4(1). Web.

Blimling, G. S. & Miltenberg, L. J. (1981) The resident assistant: Working with college students in residence halls (2nd ed.). Dubuque, IA: Kendall/Hunt.

Bridges, L. J., Margie, N. G., and Zaff, F. J. (2001). “Background for community-level work on emotional well-being in adolescence: Reviewing the literature on contributing factors”. Child Trends Research Brief. Washington, DC: John S. and James L. Knight Foundation.

Cacioppo, J.T., & Gardner, W. (1999). Emotion. Annual Review of Psychology, 50, 191-214.

Cichetti, D., Akerman, B. P. & Izard, C. “Emotions and Emotion Regulation in Development Psychology” Development and Psychopathology, 1995, 10: 1-10.

Cole, P. M., Dennis, T. A., and Martin, S. A. (2004). Emotion Regulation: A Scientific Conundrum. Poster session presented at the annual meeting of the International Society for the Study of Behavioural Development, Ghent, Belgium. Web.

Cole, P., Martin, S., and Dennis, T. (2004) “Emotion regulation as a scientific construct: Methodological challenges and directions for child development research”. Child Development, 75(2), 317–333.

Compas, B.E., Connor-Smith, J.K., Saltzman, H., Harding Thomsen, A., & Wadsworth, M.E. (2001). Coping with stress during childhood and adolescence: Problems, progress, and potential in theory and research. Psychological Bulletin, 127, 87-127.

Dyson, R. & Renk, K. (2006). Freshmen Adaptation to University Life: Depressive Symptoms, Stress, and Coping. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62, 1231–1244.

Eisenberg, N., Champion, C., and Ma, Y. (2004). Emotion-related regulation: An emerging construct. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 50, 236–259.

Ekman, P. & Davidson, R. J. The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions, 1994, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Frazier, Thomas William. Experience and Regulation of Emotion by Younger and Older Adults. (Diss. Case Western Reserve University, 2004).

Gallo, L.C., & Matthews, K.A. (2003). Understanding the association between socioeconomic status and physical health: Do negative emotions play a role? Psychological Bulletin, 129, 10-51.

Garber, J., Braafladt, N. & Weiss, B. “Affect Regulation in Depressed and Nondepressed Children and Young Adolescents.” Development and Psychopathology, 7 (1) 1995: 93-115.

Gater, R., Tansella, M., Korten, A., Tiemens, B. G., Mavreas, V. G., & Olatawura, M. O. (1998) Sex differences in the prevalence and detection of depressive and anxiety disorders in general health care settings: Report from the World Health Organization collaborative study on psychological problems in general health care. Archives of General Psychiatry, 55, 405–413.

Goldstein, S., and Brooks, R. B. (2005). “Why study resilience?” In S. Goldstein and R. B. Brooks, Handbook of Resilience in Children (pp. 3–15). New York: Springer Science þ Business Media, Inc.

Gray, J. (1992). Men are from mars, women are from venus. London: Thorsons.

Gross, J. J. (1998a). “Sharpening the focus: Emotion regulation, arousal, and social competence”. Psychological Inquiry, 9(4), 287–290.

Gross, J. J. (1998b). “The Emerging Field of Emotion Regulation: An Integrative Review. Review of General Psychology, 2(3), 271–299.

Gross, J. J. & O. P. John. “Individual Differences in Two Emotion Regulation Processes: Implications for Affect, Relationships, and Well-being” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 85 (2) 2003: 348-362.

Hoeksma, J. B., Oosterlaan, J. & Schipper, E. M.. “Emotion Regulation and the Dynamics of.” Development and Psychopathology, 75 (2) 2004: 354-360.

Izard, C. E. Human Emotions. New York: Plenum Press, 1977.

Kagan, J. “On the Nature of Emotion.” In N. A. Fox (Ed.), The Development of Emotion Regulation: Biological and Behavioural Considerations. Monographs of the Society for Research in Child Development, 59 (2-3) 1994: 73-100.

Kring, A. M. (2001). “Emotions and Psychopathology” In Emotions: Current Issues and Future Directions by Mayne T. J. & Bonnano, G. A. New York: Guilford Press.

Kohn, J. P., & Frazer, G. H. (1986) An academic stress scale: Identification and rated importance of academic stressors. Psychological Reports, 59(2), 415-426.

Lang, P.J., Bradley, M.M., & Cuthbert, B.N. (1998). Emotion and motivation: Measuring affective perception. Journal of Clinical Neurophysiology, 15, 397-408.

Ledoux, J. E. The Emotional Brain, New York: Touchstone, 1998.

Macklem, G.L. (2008). “The Importance of Emotional Regulation in Child and Adolescent Functioning and School Success”. Chapter 1 in “Practitioner’s Guide to Emotion Regulation in School-Aged Children”. Springer, New York.

Macklem, G.L. (2008b). “Emotional Dysregulation”. Chapter 2 in “Practitioner’s Guide to Emotion Regulation in School-Aged Children”. Springer, New York.

Macklem, G.L. (2008c). “Emotion Regulation in the Classroom”. Chapter 6 “Practitioner’s Guide to Emotion Regulation in School-Aged Children”. Springer, New York.

McRae, Kateri, Kevin N. Ochsner, Iris B. Mauss, John J. D. Gabrieli & James J. Gross. “Gender Differences in Emotion Regulation: An fMRI Study of Cognitive Reappraisal.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 2008; 11; 143-163.

Menesini, E. (Chair) (1999). Bullying and emotions. Report of the Working Party. The TMR Network Project. Nature and Prevention of Bullying: The causes and nature of bullying and social exclusion in schools, and ways of preventing them. Web.

Mitchell, S. A. & Black, M. J. Freud and Beyond: A History of Modern Psychoanalytic Thought, 1995, New York: Basic Books.

Muraven, M., and Baumeister, R. F. (2000) “Self-regulation and depletion of limited resources: Does self-control resemble a muscle?” Psychological Bulletin, 126(2), 247–259.

Pardini, D., Lochman, J., and Wells, K. (2004). “Negative emotions and alcohol use initiation in high-risk boys: The moderating effect of good inhibitory control”. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 32(5), 505–518.

Plattner, B. et al. (2007). “State and Trait Emotions in Delinquent Adolescents”. Child Psychiatry Hum Dev (2007) 38:155–169. Web.

Rottenberg, J. and Gross, J. J. “When Emotion Goes Wrong: Realizing the Promise of Affective Science.” Clinical Psychology: Science and Practice 2003, 10(2) 227-232.

Russell, J. A. “Core Affect and the Psychological Construction of Emotion.” Psychological Review, 110 (1) 145-172.

Salovey, P. (2006). “Applied Emotional Intelligence: Regulating Emotions to Become Healthy, Wealthy, And Wise”. In J. Ciarrochi and J. D. Meyer (Eds.), Emotional Intelligence in Everyday Life (pp. 229–248). New York: Psychology Press.

Scherer, K. (1999). Appraisal theory. In T. Daleigsh & T. Power (Eds.), Handbook of Cognition and Emotion (pp. 637-659). Sussex: John Wiley & Sons.

Schweder, R. A. “You’re Not Sick, You’re Just in Love: Emotion as an Interpretive System“. In P. Ekman & R. J. Davidson (Eds.), The Nature of Emotion: Fundamental Questions, 1994, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Silva, M., Dorso, E., Azhar, A., & Renk, K. (2007). The relationships among parenting styles experienced during childhood, anxiety, motivation, and academic success in college students. Journal of College Student Retention: Theory, Research, and Practice. 9 (2) 149-167.

Suinn, R.M. (2001). The terrible twos – Anger and anxiety. American Psychologist, 56, 27-36.

Thompson, R. A. (1991). “Emotional regulation and emotional development.” Educational Psychology Review, 3(4), 269–307.

Walden, T. A. & Smith, M. C. “Emotion Regulation“ Motivation and Emotion, 21, 7-25.

Watson, Elizabeth B. Emotion Regulation in Affluent Adolescents. (Ph.D. Dissertation: Columbia University) 2007: 1-20.

Zeidner, M., Matthews, G., and Roberts, R. D. (2006). “Emotional intelligence, coping with stress, and adaptation”. In J. Ciarrochi and J. D. Meyer (Eds.), Emotional Intelligence in Everyday Life (pp. 100–125). New York: Psychology Press.Everyday Life (pp. 229–248). New York: Psychology Press.

Zeman, J., Casano, M., Perry-Parish, C. & Stegall, C. “Emotion Regulation in Children and Adolescents.” Development and Behavioural Pediatrics, 2006, 27 (2): 155-168.