Introduction

The dual representation theory of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) was first proposed by Brewin (2001; Brewin & Joseph, 1996). This theory explains that various facets and details of traumatic events such as smell, sights, and sounds are saved or memorized. This process is known as situationally accessible memory, which somewhat resembles episodic memory (Brewin, 2007). Brewin (2006) argues that when a person reflects upon this information consciously, in an attempt to interpret or incorporate these features or details, the preceding insights are retained in a different system. This kind of memory one accesses consciously is called verbally accessible memory, which is comparable to semantic memory (Holmes, Brewin, and Hennessy, 2004).

Occasionally, when individuals have a traumatic experience, they try to distance themselves from an event in the context. According to Brewin (2006), individuals might try to amuse themselves from the memories of this incident; primarily to thwart negative emotions. According to Metcalfe and Jacobs (1998; Pillemer, 1998), the characteristic feature of PTSD is its alternation noted between avoiding trauma-linked memories and re-experiencing. According to Hagenaars, Brewin, Minnen, Holmes, and Hoogduin (2010), the memories connected with PTSD seem to appear impulsive, and often times encroaching, with a higher frequency in the consciousness of an individual. To a larger proportion, the memories, the encroaching memories involve images associated with increased physiological arousal and are experienced as a reenactment of the original trauma or “flashback” (Byrne, Becker& Burgess, 2007; Kang, Dalager, Mahanand Ishii, 2005). In addition, memories linked with past traumas may be far disconnected, contributing to aural, visual, olfactory, and physical feelings. These syndromes may have varying ranges of “flashbacks” without essentially conforming to a simple identifiable event (Byrne, Becker, & Burgess, 2007; Holmes et al, 2004). A flashback identified from memories of trauma is retrievable through routine examination of persistent memory (Elzinga and Bremner, 2002). Elzinga and Bremner (2002), contend that a deliberate, and unprompted mental activity typically involves distinct recalling of the traits of trauma and the connecting to related emotions. The emotions are evoked after having relieved or re-experienced the researchable memories qualitatively. Thus, these deliberate efforts to reconnect with memories differ from unprompted re-enactments, in which emotions or feelings are often resynthesized in their unique strength (Elzinga and Bremner, 2002; Christianson, 1992).

Description

According to Kimerling, Gima, Smith, Street, and Frayne (2007), sexual mugging in the military is a common phenomenon. Policymakers, health care providers, military personnel, and media have recognized various reports of harassment and sexual assault, not only for women but also for cadets and mission personnel (Murdoch and Nichol, 1995). The phenomenon is increasing day by day with incidence reports increasing. In the United States, for example, Kimerling et al (2007) point out that the “annual incidences of experiencing sexual harassment are about 3% among women and 1% among men in the military”.

The term “Military Sexual Trauma” according to Julio, McFarlane, Nasello, and Moores (2008), denotes sexual assault and continual, intimidating sexual provocation that occurs during military service. Military Sexual Trauma is hypothesized to be of occupational contact structure due to duty-related vulnerability. Therefore, sexual harassment and sexual assaults are linked to duty structure and hierarchy-related vulnerabilities in the military (Julio et al, 2008). Psychometric analysis utilizing various methods, according to Julio et al (2008), supports the idea that ‘Military Sexual Trauma’ is caused by sexual assault and severe types of harassment. Severe forms of sexual harassment comprise of, for example, undesirable sexual experiences, which include; touching, stroking, risky attempts to open a sexual bond. These kinds of incidences are very different from other general intimidating experiences such as derogatory comments and sexist actions. According to Grey, Young, and Holmes (2001), the United States epidemiological data provides prove and illustrates a harmful effect of sexual trauma on mental health. Among all the traumatic events noted, rape stands as one of the conditional risk factors necessitating post-traumatic stress disorder. Metcalfe and Jacobs (1998), show that detailed data collected from the military samples affirm that sexual harassment or trauma is a major risk factor for developing PTSD; and it does not help towards combating the possibility of PTSD as some may imagine. Just as it is the case for many other people suffering from PTSD, veteran and civilian women exposed to sexual harassment or sexual assault show or exhibit similar medical conditions and mental health.

Purpose

Sexual assault is a persistent phenomenon in the military. Research illustrates that about 23 – 30% of female veterans experience sexual trauma. In addition, evidence has shown that women who experience sexual trauma in the military are at a high risk of developing PTSD. In their study, Kang et al (2005) remarked that nearly 42% of women who had initially experienced sexual trauma showed syndromes of PTSD. Similarly, Pillemer (1998) noted that MST is more likely to be linked to PTSD than any other civilian and military traumatic event.

According to Kang et al (2005), gender response to MST differs and there has been no empirical data contrasting the MST to sexual harassment or trauma occurring outside the military service. Kang et al (2005), point out in 2005 research done on Gulf War veterans observed that exposure to sexual harassment during women’s placement provided a higher risk of forming PTSD later on when exposed to combat experiences. Similarly, it was established by Kang et al (2005), that in 2002, about 2% of active military women and 1% of duty men experienced sexual harassment or violence. Furthermore, recent statistics have found out that about 6.8% of women on duty and 1.8% of men recounted unwanted sexual encounters

Global security issues affecting the United States have called for American participation in various war frontiers around the world. This is obvious given the current war initiatives in; Afghanistan, Iraq, and what is happening in the Arab world. Hence, it is pressing to understand how this war situation is affecting women war veterans and how effective measures can be set up (Murdoch and Nichol, 1995; Siegel, 1999). The numbers of women engaging in armed combat and other conflicts have continued to increase, hence higher triggers and incidence of MST and PSTD. It is of important to analyze how their experiences during the combat mission can generate syndromes leading to PTSD.

By evaluating how MST manifests in women veterans, it is possible to formulate a better treatment strategy. Such a strategy will effectively utilize the scope of PTSD syndromes and how they fit in various cases and settings pertaining to the women veterans (Ozer et al, 2003; Metcalfe and Jacobs, 1998).

The other important purpose of this research is to contribute towards more awareness with regard to women exposed to war-linked trauma. The majority of women veterans suffer from military sexual trauma. This assertion is illustrated by statistics from the Veterans Administration and civilian health care systems. There is a misconception that women suffer more or are most affected by exposure to combat. However, it is the position of this paper that this is mere gender stereotyping and the real cause of trauma among women veterans has to do with sexual harassment.

Theoretical Concepts

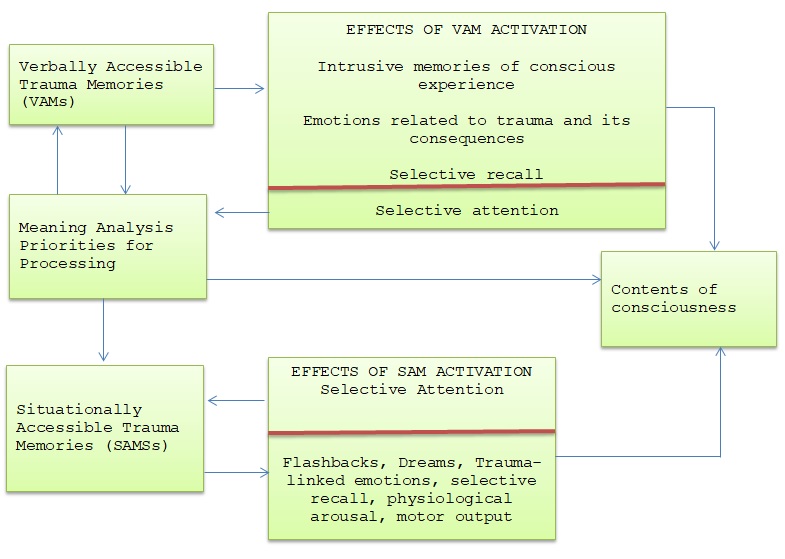

According to Brewin (1996), the dual representation theory comprises a two-route mode of memory. Each of the two routes serves one of the two classes of memory i.e. the declarative and non-declarative memory (Cahill and Mcgaugh, 1998). The dual representation theory offers a verbally accessible memory system. Such memory i.e. the verbally accessible memory is the medium in which clear descriptions of spoken memories are designated. According to Brewin (2007), the situationally accessed memory system, (SAM) is the conduit for inherent memories controlled by sensory, emotional, perceptual, and motor imprints. Holmes et al (2004), explain that the verbally accessed memory, VAM, is unified in nature, purposefully retrievable. VAM, to a large extent, receives cognizant thought’s dispensation that is declarative (Siegel, 1999). This is in contrast with SAM, which can be activated compulsorily and incites the primary emotions and biological responses connected with the memory (Matto, 2005; Tinnin, 1990).

Additionally, these two systems in dual representation theory contrast in terms of encoding of verbal accessed memory and are anchored on responsiveness. This means that there is a considerable level of imperfectness because of its temporal-spatial framework of encoding (Tinnin, 1990). Since SAM does not encode chronological and spatial data or information in a given context, which needs attentional resources, it has low capacity limits (Brewin, 2007).

According to Matto (2005), DRT suggests that there are different effects of trauma on the aforementioned systems because of the increased percentage of peri-traumatic stimulation and attentional apprehensions of the threatening condition. Cahill and Mcgaugh (1998) contend that stimulation limits the capacity and the quality of trauma-related data and information, which can be recorded in VAM. This is to say, the increased stimulation during trauma constraints the encoding of event-relevant spatial chronological and other contextual information. Hence, this influences the capacity of the memory system to account for various events and thus to contextualize them as part of a past event. The high sensory, emotional, and perceptual (fear) requirements of trauma prioritize recording and encoding with the SAM system (Holmes et al, 2004). The DRT theorizes that the PTSD pathology results due to the equilibrium of VAM and SAM.

The sensory and perceptual memories found in trauma from SAM are readily activated because of the simplification of trauma memory in the SAM system. This is because the memories miss the context and are experienced as “in the present” (Holmes et al, 2004). These memories comprise the sensory, which encompasses the olfactory, auditory, visual, and others. Besides, the physiological and motor characteristics of traumatic experiences are characterized in a situationally accessible knowledge in a form of analogical ciphers that promote unique experiences to be remodeled (Brewin, 2007; Cruwys and O’Kearney, 2008). These ciphers form part of the larger representation. Hence, they entail; stimulating information automatically which is coded for its ability to discriminate the trauma from previous non-traumatic situations. The victims interpret the happening by employing; novelty, information derived from initial associative learning. Individuals, within themselves, have innate and non-conscious appraisal mechanisms at their disposal. Individuals employ these appraisal mechanisms towards the achievement of universal goals such as attachment to caregivers or regulation of status within the social hierarchy and how information about the person is utilized (Pillemer, 1998).

The DRT also sketches the involuntary activation of SAM, creating the sensations or re-experiencing syndromes. Such activation increases the insistent stimulation and the independent sense of danger and distress with which PTSD is widely associated. According to Brewin (2001), the arousals wield an inhibitory impact on the VAM. Moreover, they support evading-trauma-related maladaptive efforts aimed at escaping from pain or danger. These efforts to escape pain and danger are specifically important in triggering the imbalance of VAM and SAM. When the imbalance happens, non-event-relevant triggers lead to re-experiencing and stimulation of dysfunctional signs associated with PTSD (Kang et al, 2005).

According to Grey et al (2001), the physiognomies of non-conscious dispensation, for example, extreme swiftness, are resultant from the analogous dispensation of several inputs. When an analogous dispensation of several inputs is realized, it permits more detailed and extensive computations. Such extensive computations are more than what conscious dispensation does. However, their role is restricted by its serial number, slowness, and inability of an individual to keep a limited amount of information in memory at a given time. Similarly, Pillemer (1998) posits that the output of these forms of dispensation or processing is kept or stored in diverse locations. Moreover, such output is stored in different codes (Grey et al, 2001). Brewin (2001), in his research, pointed out that various conduits might sanction sensory connections with emotional actions without being exposed to cortical processing. Brewin (2001) in relating these ideas to the experience of trauma pictured that, from the outset, more than one form of representation of an experience of a single or recurring trauma prevails. This assertion is similar to the theoretical work of Teasdale and Bernard (1993), which is based on interrelating rational sub-systems and the multiple-entry integrated memory system. Teasdale and Bernad (1993) underline the need for integrating more than one level of representation in view of understanding the complex link existing between emotions and cognizance. Thus, according to Brewin (2001), the activities of hormones in the brain decrease the neural anatomical systems serving conscious processing and supplement activity systems servicing non-conscious perceptual and memory processes in an individual with acute trauma.

Relationship Between the Concepts

Byrne et al (2007), assert that voluntary and involuntary memory is contingent on similar systems in the brain of an individual with the voluntary memory engaging prefrontal areas as a fragment of the deliberate search dispensation. Both the image and the memory appear to depend on similar systems encompassing medial pre-frontal areas, posterior areas in the medial and adjacent parietal cortexes, the lateral temporal cortex, and the MTL (Byrne et al, 2007; Johnson and Multhaup, 1992).

A collective theme occurring through the work appraised in the preceding paragraphs is the difference existing between the representations that seize unrefined sensual data and illustrations that are more theoretical. Although the fitting terminology and differences exist owing to the varying phenomenon under research, a vital link exists between the ideas of dual representation theory. According to Byrne et al (2007), the memory system that programs senses, so long as the brain allows, in an exceptional style, and in the style they were perceived or experienced, relays them wholesome back into consciousness. Such memory is depicted experiences in an egocentric and depictive way. Information stored in these structures can be triggered by similar responses, with prompts often comprising of low-level sensory structures. The second system program or code, which is perceived in aspects such as abstract properties, is collective across experiences. Such a system comprises, for example, allocentric, structural properties and VAM (Brewin, 2001; Byrne et al 2007). These representations can be utilized in recreating images consistent with the experienced events from any perspective. Information in this system can also be merged flexibly to respond to unique circumstances that include narration, communication, and planning (Cruwys & O’Kearney, 2008).

SAM organization embraces low-level representation, which is firmly intended for its sensory and working abilities. Hence, in PSTD, particularly traumatic events are recorded as SAMs without necessarily associating to the VAM structure. This simplifies retrieval of SAMs to be activated automatically by internal or environmental (situational) cues evocative of the novel trauma without salvage of the suitable factual context.

The loss of association between VAM and SAM systems has important in PTSD. According to Pillemer (1998), the narrowing of attention urged by extreme stress and the decrease in hippocampal purpose suggests that little or less information about a supposedly life-threatening experience can be recorded or stored in a deliberately present form (Rullkoetter et al, 2009).

This decrease in encrypting may be surged by pre-traumatic sensitivity, which entails approaches of mental downfall or dissociation. This is because the data or information is considered by the individual as important for future existence and survival. Therefore, it is seized in terms of sensory images, prompting enough capacity of data or information to be processed in analogous and stored (Hagenaars et al, 2010). Besides, flashbacks are inclined towards an adaptive process in which recorded data is presented and processed in detail even when the situation prompting danger has passed. PTSD in tandem with this account replicates the letdown of the epitomized information to be carried. Rather, the stressful images are shunned and never connected with their fitting context (Hagenaars et al, 2010).

Theoretical Assumption

The notion that conscious emotional processing may be prematurely inhibited is an important feature of dual representation theory, which has not been adequately explored or accorded due attention. This feature designates that the theory can be accounted for easily. This is unlike other models of the same for the erratic sequence of PTSD. It is asserted that with repeated reflection, with coverage of fitting cues, emotional dispensation may recommence years after it seems to have ended. The theory also explores the clinical interpretations of patients who appear to have never consciously processed trauma, but have on occasion, experienced severe nightmares. This could suggest or represent a severe sign of restraint of conscious processing (Christianson, 1992). Furthermore, syndromes not established by the theory include dissociative reactions and emotional numbness.

In tandem with other researchers, Christianson (1992), asserts that emotional numbing is a type of psychic analgesia, similar to complementary physical analgesia that safeguards an individual from overstimulation. Whereas emotional numbing may seem to be a pre-programmed reaction that is not under the influence of the conscious section of the brain, dissociation may be connected to a learned process because of repeated or prolonged trauma. The dual representation model illustrates that these two responses to a given or specific trauma may be programmed with equivalent SAMs and when activated by fitting cues may be restored in tandem with other facets to situationally accessible knowledge.

Implication for Research

Various research such as the one pointed out by Brewin (2007) assert that PTSD contributes to the identification of clinical conditions or features of PTSD linking it to acute trauma. Such conditions include; re-experiencing symptoms, i.e. intrusive memories and nightmares; the protective reactions in terms of emotional numbering, cognitive avoidance, amnesia, and arousal signs such as hypervigilance and startle response (Cruwys & O’Kearney, 2008; Christianson, 1992). PTSD embodies various negative emotions such as negative cognitions, anger, and sadness. Unlike other theories, dual PTSD settles a distinction between diverse types of intrusive signs, epitomized by recurrent accessing of SAMS and VAMs. The strengthened accessibility of VAMs and SAMs and their connected emotional influences contributes to the familiar signs of arousal.

Dual representation theory entails the deliberation of apparatuses that are explicit to PTSD and the universal reaction to trauma. Hence, the symptoms lasting for one month are vital for diagnosing PTSD in DSM-IV. DSM-IV can seize individuals, who positively affect their trauma processing those who are susceptible to undergoing severe or protracted emotional processing, or those individuals who will impulsively impede this processing. In this case, the dual representation theory is important because it predicts the contrasting judgments in relation to intrusive memories and succeeding syndromes (Brewin & Hutchison, 1996).

According to Brewin and Hutchison (1996), this case presents two important arbitrator variables i.e. the level of trauma and the duration of time taken since the trauma occurred. In mild trauma, a proportion of a person is probable to encounter intrusive memories for longer periods, and lengthy intrusions may suggest a surged likelihood of which may contribute to a psychiatric disorder.

Concisely, the theory provides an important pointer in those emotions characterized in terms of anger, and guilt gives a hint in upholding PTSD syndromes. This is because of the dependability of aversive secondary emotions that inhibit the orientation of trauma to SAMs, PSTD is connected with acute emotional processing (Cruwys and O’Kearney, 2008).

In present studies, dual representation theory, PTSD is distinguished from other maladies by the presence, and the existing stages of instigation of trauma-interrelated SAMS. Other syndromes, which include fear or phobia, depression, and general anxiety conditions, do not need necessarily demand trauma interrelated memories. That notwithstanding, in a certain stage, these may habitually be present. Additionally, PTSD obliges these memories to be readily triggered, as explained by the presence of impulsive intrusive sensations or conscious energies of avoidance.

This is why the theory is accountable for what Himmelfarb and Mintz (2006) recently confirmed in patients. Himmelfarb and Mintz (2006) noted that patients diagnosed with severe depressive episodes also indicated the presence of regular intrusive memories; predominantly of past stressors that entailed childhood trauma.

The theory notes that processing these events, which were prematurely subdued, prompts emotional memories to endure and then be restarted by future depressions or life events (Rullkoetter et al, 2009; Barr et al, 2007). This is probably because there are many reasons why it is challenging for children to process obnoxious memories. According to Barr et al (2007), even when children reveal abuse, often, the existence of influential forces on them not to leak the information may impede proper communication. Consequently, children reporting sexual abuse may not be understood, and on occasion when they are understood, there will be a lack of sufficient adult sufficient understanding, responsiveness, and accountability to enhance this process (Barr et al, 2007).

Currently, a high prevalence of comorbidity towards integrating other disorders exists. For example, a hereditary combination of psychiatric syndromes in the lineages of patients experiencing PTSD may incriminate more universal genetic and psychosomatic susceptibilities that are significant in the dawn of PTSD. Contrasting other data or information-processing models, dual representation models provide extra explicit submissions in reconnoitering the increased frequency of comorbidity associated with other maladies.

To explain, depression may culminate into the emotional loss of the real characteristic significance of trauma. This may lack feelings in the case of breakage of a relationship, loss of another person, mental or physical loss, loss of future objectives, and a sense of actual self among other losers (Andrews, Brewin, Rose & Kirk 2000). Breakage of connection in self in terms of caring, morals, and altruistic or effectiveness in terms of self-control may prompt depression embodied in the feelings of shame or guilt (Andrews et al, 2000). Depression may also gradually lead to promptings of secondary response to enduring emotional processing and the ensuing feelings of loss of mental authority and powerlessness.

Evidence of and application of dual representation has also been found through application in experimental findings in laboratories. According to Brewin (2001), the dual representation theory suggests that substances of VAMs and SAMs are capable of prejudicing various ranges of perceptive processes. Perception and attention processes are prejudiced in terms of information accepted or entertained, which is consistent with a person’s dynamic goals, concerns and plans. According to Brewin (2001), this information is represented in VAMs and SAMs. Hence, after a traumatic exposure, interrelated information is represented in layouts recognized by VAM and SAM. Therefore, the information is in a position to compel perception and attention process to information available in the environment that is matching with the trauma (Brewin, 2001; Andrews et al., 2000). Therefore, prejudice of perception and attention towards trauma-linked information would be predictable in patients experiencing PTSD.

The implication of dual representation theory for the future encompasses various aspects, which the current context does not fulfill. For instance, when it comes to the treatment of patients suffering from PTSD, behavioral-based methods encompassing exposure to traumatic memories need to be strengthened. Moreover, there is a need to clearly distinguish between predominantly anxiety-based and other emotional reactions occurring during a traumatic period. However, it is considered that the dual representation theory should not isolate ancillary emotional responses emanating from succeeding conscious judgment, which is not probable to orientate but should react to perceptive psychotherapy strategies. Exposure treatment when applied in dealing with aversive ancillary or multifaceted emotions such as guilt should be reinforced to evoke the trauma. According to Brewin (2001), if the traumas SAMs triggered in therapy are repetitively harmonized with aversive ancillary emotions ascending from conscious judgment, there will be limited or drop in undesirable effects and thus, the conditioning of fear will eventually be obstructed.

Furthermore, the dual representation theory will tend to alienate theoretical designs that are aimed at comparing individuals already experiencing PTSD and those who have been exposed to similar trauma. This is because, these individuals may consist of individuals who in one way or another have successfully completed emotional processing, and others would have prematurely inhibited the PTSD. The two kinds of individuals have differing cognitive characteristics, therefore, embracing one theory to apply to both sets of individuals may be misleading hence can give a false finding (Cruwys & O’Kearney, 2008; Barr et al, 2007).

Application of Research in PTSD in Military Personnel

The psychological influence of military service and linked experiences has been widely explored by various researchers. Interest in such like research became prevalent during the Vietnam War and has been ongoing leading researchers to research recent wars in Iraq and Afghanistan among other jurisdictions. According to Himmelfarb and Mintz (2006), the major stressors among women military personnel range from sexual assault to dangerous occupational duties. Initially, only female army nurses were exposed to combat situations (Himmelfarb & Mintz, 2006). In earlier research on women and combat-linked stress, 50% of women Vietnam veterans had syndromes pointing to PTSD, 20% exhibited major disruptive syndromes. To reduce the syndromes, the military personnel resorted to various coping patterns. Common coping mechanisms or patterns entailed self-blame, concentrating on negative effects and intuitions. The coping patterns were evident in terms of women veterans seeking emotional support, searching for reasons in events experienced, and expressing feelings linked with effective psychological functioning (Himmelfarb & Mintz, 2006; Cruwys & O’Kearney). The efforts of women veterans to cope notwithstanding, the aforementioned syndromes i.e. self-blame, withdrawal, and stress were evident in them; these syndromes are indications of vulnerability to PTSD.

Himmelfarb & Mintz (2006) argue that the understanding of PTSD has a major role to play in dealing with trauma in the military. Thus, understanding clinical information related to PTSD can provide needed information so that fitting interventions can be implemented. It is vital that mental health programs, using PTSD information can tailor treatment methods to MST-prone patients. Besides, PTSD can be dealt with through behavioral intervention, which has to be in line with the medical needs of patients, thus helping decrease morbidity (Andrews et al., 2000; Kang et al., 2005).

Conclusion

Understanding PTSD involves understanding methods, which simplify trauma encoding, and the association between emotions. Moreover, understanding PTSD requires the capacity to identify and appreciate emotion appraisal mechanisms in individuals, among other vital elements. One of the alternatives readily available for achieving this is specifying in-depth the processes that accelerate or impede PTSD. However, this needs hypothetical elaboration of various aspects of dissociation, especially conceptual processing, and data-led processing.

Memory organization, as mentioned in the paper, is a risk-predisposing factor in PTSD. Hence, it is of imperative importance for the theory to frame reliable methods of containing conditions, which can create or precipitate its cognitive power. For example, disorganization in the account reflects the inadequacy in the fundamental memory representation, where difficulties can be observed in articulating contents of memory or retrieval. Degeneration in a reminiscence exemplification may happen in the successions of images, distinct images, or by a comprehensive narrative.

Trauma is connected with several causative agents. As mentioned in the paper, the negative perception of self, negative beliefs, and identities provide room for full-blown PTSD. However, little information or knowledge has been amassed in terms of their nature and structures. Research indicates that emotions such as guilt and anger among other negative emotions are common features of PTSD. Similarly, shame arbitrates the relation between childhood hardships and subsequent PTSD signs in trauma sufferers. It is probable that the nature and structure of triggering elements, as earlier noted, are chiefly involved in understanding how trauma affects a person.

References

Andrews, B., Brewin, C. R., Rose, S. & Kirk, M. (2000). Predicting PTSD symptoms in victims of violent crime: The role of shame, anger, and childhood abuse. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 109, 69-73.

Barr, R., Muentener, P. & Garcia, A. (2007). Age-related changes in differed imitation from television by 6- to 18- month-olds. Developmental Science 10:6, 910-921. Web.

Brewin, C. R. (2006). Understanding cognitive-behavior therapy: A retrieval competition account. Behavior, Research and Therapy, 44,765–784.

Brewin, C. R. (2007). Autobiographical memory for trauma: Update on four controversies. Memory, 15, 227–248. Web.

Brewin, C. R., Gregory, D. J., Lipton, M., and Burgess, N. (2010). Intrusive images in psychological disorders: Characteristics, neural mechanisms, and treatment implications. Psychological Review, 117, 210-232. Web.

Brewin, R. C. (2001). Memory processes in posttraumatic stress disorder. International Review of Psychiatry, 13, 159- 163. Web.

Brewin, C.R., Christodiulides, J., & Hutchison, G. (1996). Intrusive thoughts and intrusive memories in a non-clinical sample. Cognition and Emotions, 10, 107-112.

Byrne, P., Becker, S., & Burgess, N. (2007). Remembering the past and imagining the future: A neural model of spatial memory and imagery. Psychological Review,114, 340–375.

Cahill, L. & Mcgaugh, J.L., (1998). Mechanisms of emotional arousal and lasting declarative Memory. Trends in Neurosciences, 21, 294–299.

Christianson, S. A. (1992). Emotional stress and eyewitness memory: A critical review. Psychological Bulletin, 112, 284–309.

Cruwys, T., and O’Kearney, R., (2008). Implications of neuro-scientific evidence for cognitive models of posttraumatic stress disorder. Clinical Psychology, 12, 67-76.

Elzinga, B. M., & Bremner, J. D. (2002). Are the neural substrates of memory the final common pathway in posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD)? Journal of Affective Disorders, 70, 1–17.

Grey, N., Young, K. & Holmes, E. (2001). Hot spots in emotional memory and the treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 29, 367–372.

Hagenaars, A. M., Brewin, R. C., Minnen, A., Holmes, A. E., & Hoogduin, A.L. K. (2010). Intrusive images and intrusive thoughts as different phenomena: Two experimental Studies. Psychology Press, 18, 76 – 84.

Himmelfarb, N., Yaeger, D., & Mintz, J. (2006). Posttraumatic stress disorder in female Veterans with military and civilian sexual trauma. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 19, 837-846.

Holmes, A. E., Brewin, R.C., & Hennessy, G. R., (2004). Trauma films, Information processing, and intrusive memory development. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 133, 3- 22. Web.

Julio, F. P. P., McFarlane, A., Nasello, G., A., & Moores, A. K., (2008). Traumatic memories: Bridging the gap between functional neuroimaging and psychotherapy. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 42, 478 -488.

Kang, H., Dalager, N., Mahan, C., & Ishii, E. (2005). The Role of sexual assault on the risk of PTSD among Gulf War Veterans. Ann Epidemiol. 15, 191–195.

Kimerling, R., Gima, K., B. A., Smith, W. M., Street, A., & Frayne, S., (2007). The Veterans health administration and military sexual trauma. American Journal of Public Health, 97, 12.

Matto, H., (2005). A bio-behavioral model of addiction treatment: Applying dual representation theory to craving management and relapse prevention. Substance Use and Misuse, 40, 529-541. Web.

Metcalfe, J. & Jacobs, W. J. (1998). Emotional memory: The effects of stress on ‘cool’ and ‘hot’ memory systems. The Psychology of Learning and Motivation, 38, 187–222.

Murdoch, M., and Nichol, K. L. (1995). Women Veterans’ experiences with domestic violence and with sexual harassment while in the military. Arch Fam Med. 4, 411-418.

Ozer, E. J., Best, S. R., Lipsey, T. I., & Weiss, D. S. (2003). Predictors of posttraumatic stress disorder and symptoms in adults: A meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 129, 52-73.

Pillemer, D. B. (1998). Momentous events, vivid memories. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Rullkoetter, N., Bullig, R., Driessen, M., Bello, T., Mensebach, C., & Wingenfeld, K., (2009). Autobiographical memory and language use: Linguistic analyses of critical life event narratives in a non-clinical population. Appl. Cognt. Psychol. 23, 278- 28. Web.

Siegel, D. (1999). The Developing Mind. New York: The Guilford Press.

Tinnin, L. (1990). Biological processes in nonverbal communication and their role in the making and interpretation of art. American Journal of Art Therapy, 29, 9–13.