Introduction

I currently serve as the Director of Pupil Services for the Wyomissing Area School District in Berks County, Pennsylvania. The geographical area of the Wyomissing Area School District includes three boroughs which roughly cover 4.8 square miles. The population is approximately 14,600 based on 2016 census figures. Outstanding educational and extracurricular opportunities are provided across all grades for our approximately 1,960 students. The District has three buildings: Wyomissing Hills Elementary Center, grades K-4; West Reading Elementary Center, grades 5-6; and our Junior-Senior High School which houses grades 7-12. Within the three buildings, there are approximately 325 total staff members. As the Director of Pupil Services, I hold responsibility for the leadership, supervision and management of our special education department, gifted education department, mental health initiatives, school nursing department and provide some oversight to other departments in a shared manner with our assistant superintendent. In addition to my core job responsibilities, I began an employee wellness committee about 4 years ago partnering with our medical insurance carrier. A small group of professional and support staff joined me and we named our committee WyoWell. We work to provide staff with free, or deeply discounted, opportunities to make their own wellness a priority. Our committee focuses on physical, mental, social, environmental, intellectual, career, family and financial wellness.

This committee work is what made me become interested in this research topic. Although we continue to offer opportunities for staff, participation is low and staff continue to report a poor sense of well-being within their work environment. We were hopeful the activities, education and resources we were providing for staff through our WyoWell initiatives would help our district leadership to see changes in overall attitudes and well-being of staff. It is my hope that this research will help me to make our WyoWell committee more productive and effective in supporting staff wellness in the Wyomissing Area School District.

Purpose of the Study

Instructional staff have a critical role in the provision of quality educational programs for students and are responsible for creating a safe learning environment and developing strong student-staff relationships while also teaching academic and functional skills across multiple domains. These staff members face many challenges due to the high demands and variety of work stressors they experience daily. These challenges often lead to burnout, frequent teacher absences, and teacher turnover. The Wyomissing Area School District has seen a significant increase in employee related stress and overall dissatisfaction in the school environment since returning to school following the mandated school closure due to the global pandemic. Additionally, an increase in the number of employees utilizing our Employee Assistance Program has been noted and reported by our provider. This capstone project seeks to better understand the staff’s perception of their own mental well-being in the school environment and how district leadership can better support staff mental well-being and address work climate and employee morale.

Research Procedures and Questions

Portions of the “Panorama Teacher and Staff Survey” created by Panorama Education, as well as portions of the “Employee Wellness Survey” created by Capital Blue Cross, will be used to gather information from teachers and instructional support staff to better understand their perceptions of their mental well-being. Teachers and instructional support staff will be defined as professional and support staff who work directly with students instructing and/or supporting the acquisition of academic skills. The survey questions will provide the opportunity to gather mostly qualitative data, however some qualitative data will be retrieved from the survey results. The following research questions will be investigated:

- Do staff have a positive perspective on their own professional well-being?

- Do staff view the response to their professional well-being by school leaders positively?

- What supports and services do staff believe they need to better support their professional well-being?

Significance of the Study

With the steady increase of additional responsibilities and duties of school employees, instructional staff are reporting similar increases in poor mental health, physical and mental exhaustion and high levels of stress. In order for these staff members to be able to effectively support their students’ social emotional needs, their own basic needs must be met. We recognize wellness includes how people feel and function in their daily jobs. Statistics show that nationally, many employees are not in good health and their work performance suffers as a result (Schultz & Edington, 2007). Physical and emotional health concerns can lead to high rates of absences and presenteeism, as well as lower productivity and performance (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention 2015). Teacher stress is linked to burnout, reduced job satisfaction, lower student academic performance, and high turnover, with the cost of turnover in schools estimated at over $7 billion nationally each year (Hui & Grandner, 2015). Although the Wyomissing Area School District implemented an employee wellness committee four years ago, along with other initiatives to develop a more positive work environment and boost employee morale, we continue to see a decrease in informal reporting of employee well-being. This project will allow for formal data to be collected to provide recommendations for school leaders to better support employee mental well-being.

Assumptions

From informal conversations on the topic of occupational wellness, as well as our WyoWell committee reviewing research related to this area, it is assumed the perspectives shared from instructional staff will be generally negative. Following the pandemic, studies across the country have revealed significant decreases in teacher attitudes toward their professional careers. Within this research, participants are asked questions related to their needs for support from district leadership, and it is excepted participants will report they need things that are outside of their contract (ie. additional time off, additional preparation time, etc.). Finally, it is assumed, and hoped for, that this research will allow the district to have data to support its decision making when looking to increase staff wellness opportunities and support for staff making their own wellness a priority.

Literature Review

This chapter focuses on the review of literature concerning the topic of discussion in detail. In particular, the chapter focuses on the discussion of two broad concepts, including occupational stress and employee assistance programs. Additionally, the chapter discusses the role of teachers and instructional staff, the role of school leaders in supporting instructional staff, and the occupational wellness programs. The chapter is ended with a short summary of results. The purpose of this literature review was to provide an overview of the current body of knowledge concerning the problem of occupational stress and perceived well-being among instructional staff.

Occupational Stress

Stress in the workplace is often referred to as occupational stress. The basis of the concept is that a work environment has certain demands, and that problems in meeting these demands and expectations can lead to illness or psychological distress. Both individual employees and whole organizations can experience occupational stress as a major health problem which can lead to burnout, physical illness, absenteeism, increased turnover and reduced performance and efficiency in completing work tasks (Stacciarini and Troccoli, 2003). The meaning developed over the years has changed significantly and research has promoted this shift to better help employers support their employees.

Prior to 1980, occupational stress was identified as the pressure from the work environment that is put on the employee, but in more recent years, occupational stress has been defined more as the relationship between a situation and the employees’ reaction towards it (Ongori & Agolla, 2008). When an employee cannot meet the demands or expectations of their job, they will feel stress (Ongori & Agolla, 2008). Ongori & Agolla (2008) also point out that stressful situations can occur when an employee realizes that the requirements of their work are greater than they can handle and even more significant when those demands continue for a long period of time. Finally, Ongori & Agolla (2008) note that although work place stressors often have negative impacts on employers, employees and whole systems, a healthy level of occupational stress is needed to increase motivation and encourage employees to take initiative.

According to Dianz and Cabrera (1997), stress occurs when the work demands and expectations that are being placed upon a person tax or exceed available resources as appraised by the individual involved. When stressful situations actually occur as a result of meeting occupational demands, employees often forget previously learned knowledge to effectively manage their responses to these stressful situations. Work overload, variations in workload, role conflict and role ambiguity are some of the most researched variables related to occupational stress and job burnout. Work stress has been shown to result in job dissatisfaction, burnout (physical, emotional and mental exhaustion), staff turnover, occupational illness and injuries, reduced mental health, depression and even suicide (Dianz and Cabrera, 1997).

Quick and Henderson (2016) addressed conflict in their research related to work environments. Throughout their research they note that every place they mention the term ‘conflict’, a reader could easily apply the term ‘stress’. They found that conflict in the work place creates stress in the workplace and stress in the workplace creates conflict. The end result of Quick and Henderson’s (2016) research noted eight cost factors to look at when dealing with stress/conflict in a work setting:

- Use of health care for illnesses and injuries that are partially psychogenic. The calculation is based on the percentage of the psychogenic components of medical problems that occur when specified stress/conflict takes place.

- Lowered job motivation. The calculation is based on the loss of productivity due to the stress/conflict event.

- Lost work time. The calculation is based on sick days, personal leave and lost time due to disciplinary actional taken during stress/conflict.

- Wasted time. This occurs primarily through the loss of an administrator’s time spent resolving stress/conflict.

- Reduced decision quality. Administrators and work teams should ask, ‘What opportunities were lost by poor decisions that were affected by stress/conflict and what might have been gained if a better decision had been made?’

- Loss of skilled employees. Chronic unresolved stress/conflict can be a decisive factor in many of the voluntary employee departures.

- Restructuring. The redesign of workflow may be altered in an attempt by administration to reduce the amount of interaction among employees.

- Sabotage, theft and damage. The prevalence of employee stress/conflict and the amount of damage and theft of inventory and equipment are often related.

The workplace stands out as a significantly important source of stress simply due to the amount of time and physical presence spent in this setting. For most professions, though, the stress inducing features of the workplace go significantly beyond the time involved (Faulkner and Patiar, 1997).

Occupational stress is a significant bother in both public and private sectors that is affected by numerous factors. Kendall et al. (2000) conducted an in-depth study determining factors that contributed to occupational stress among employees in different spheres. Kendall et al. (2000) classified all the factors into six major groups, including personal characteristics, job demands, organizational climate, interaction patterns between the worker and the job, organizational culture and socialization, and human resource management practices. Among personal factors, Kendall et al. (2000) mentioned cognitive and personality disorders, overall negativity, family-work conflicts, inadequate personal and environmental resources, and lack of coping strategies (Kendall et al., 2000). Factors associated with job demands included increased workload, pressure for quality, pressure for time, unclear work rules, and conflicts at work (Kendall et al., 2000). Personal and job-demand factors are described as the most impactful on occupational stress and employee well-being.

Workplace climate is also a significant factor that may contribute to occupational stress. Hoy (1990) describes workplace climate as the employees’ perceptions of environment at work. In other words, workplace climate is a set of implicit characteristics of the organization as perceived by employees. Kendall et al. (2000) stated that if the organizational climate is characterized by globalization trends or increased depersonalization due to the increased use of technology, it can contribute to work stress of the employees.

Interaction between work and job is also a crucial factor that contributes to occupational stress. Kendall et al. (2000) state that employees try to find workplaces that are congruent with their social, emotional, physical, and psychological characteristics. Such a congruency between person and the workplace is known as a concept of person-environment (P-E) fit. P-E fit can be identified as the extent of compatibility between an individual and the environment (Xiao et al., 2021). Specifically, Andela and Van Der Doef (2018, p. 2) determine P-E fit as “the compatibility between an individual and a work environment that occurs when the characteristics are well matched.” The lack of person-environment fit is usually associated with increased stress, low employee loyalty, and decreased workplace satisfaction (Xiao et al., 2021). Thus, it is crucial for the human resource department to select the employees carefully and ensure the workplace environment fits the key staff members.

Organizational culture also plays a central role in the amount of occupational stress a person may experience. Organizational culture is a set of implicit and explicit rules, values, traditions, vision, and mission (Hoy, 1990). If a person is uncomfortable with the workplace culture, or the workplace culture is destructive in its nature, a person is likely to experience an increased amount of occupational stress (Kendall et al., 2001). The common modes of distractive workplace culture include discrimination, bullying, and workplace hostility (Kendall et al., 2001).

Human resource practices also place a crucial role in the amount of accumulated stress. In particular, devolution of the direct human resource practices associated with the decentralization of the HR functions and decreased direct involvement in managing personnel has led to decreased control of the employees’ well-being (Kendall et al., 2001). As a result, organizations fail to meet the needs of the employees, which leads to increased occupational stress (Kendall et al., 2001). Inadequate performance appraisals and assessment practices from the human resource department may also lead to increased stress among employees due to the lack of predictability of evaluations (Kendall et al., 2001). Thus, order to avoid the negative consequences of occupational stress described by Quick and Henderson (2016), organizations should ensure to employ the best human resource practices.

Apart from internal stressor that can be controlled by the organization, there are external factors that may contribute to occupational stress. The COVID-19 pandemic was one of the unprecedented events in the recent history that had a tremendous impact on workplace stress in various industries (Prasad et al., 2020). The pandemic led to significant changes in the workplace culture of all the organizations due to lockdown measures, changes in the workplace cultures, and alterations of the workflow (Prasad et al., 2020). As a result, employees were forced to adapt to the new realities, which affected person-environment fit (Prasad et al., 2020).

The COVID-19 pandemic had the most impact on occupational stress among healthcare professionals. The healthcare professionals experienced increased amount of stress due to increased workload, which led to work-life disbalance, chronic fatigue, and burnout (Magnavita et al., 2020). Moreover, healthcare employees were forced to work in the conditions of constant contamination threat (Sriharan et al., 2021). Increased occupational stress led to growing turnover, decreased productivity, low workplace satisfaction, and high nurse frontline employee shortage (Magnavita et al., 2020).

Other industries were also affected by increased workplace stress due to the pandemic. In particular, teachers reported increased stress due to remote work, increased workload due to training, and changes in the work routine and workplace culture (Minihan et al., 2022). Chitra (2020) reports that online classes were the central source of increased occupational stress among teachers, leading to decreased workplace satisfaction. Sönmez et al. (2020) report that the pandemic had a significant impact on occupational stress among the hospitality workers. Stress was associated with the fear of job losses, as the sector was affected the most by the pandemic due to lockdowns and migration restrictions (Sönmez et al., 2020). Thus, occupational stress cannot always be controlled by the organization, as the external factors contribute significantly to the occupational stress.

Teacher Instructional Support Staff Stress

Prior to the COVID-19 pandemic, teaching was a stressful occupation. Research has shown 40-50% of teachers leave the profession within the first 5 years (Ryan & Deci, 2017). Studies have previously defined teacher stress as “the experience by a teacher of unpleasant, negative emotions, such as anger, tension, frustration or depression, resulting from some aspect” of being responsible for the teaching and support of children in the K-12 setting (Kyriacou, 2001, pg. 28). Moreover, instructional staff stress can be reported as related to demands and pressure, staff inability to cope with those demands and staff burnout (Kyriacou, 2001). Understanding instructional staff stress and how it can influence them in several ways, most importunately burning out and quitting all together, will only help the education system to succeed, not just individual staff (Klassen & Chiu, 2010). Along with stressors, teachers face a multitude of challenges that may induce anxiety, such as educational policies, teacher-parent relationships and other relationships within the school environment (Shillingford-Butler, Patel, & Ngazimbi, 2012).

Nayak (2014) defined anxiety as “a feeling of fear, worry and uneasiness, usually generalized and unfocused as an overreaction to a situation that is only subjectively seen as threatening” (p. 2). Additionally, Nayak (2014) stated that anxiety is not a normal response to a stressful situation, and responses can range from physical to mental. For example, in a work environment, a person may feel anxiety due to the amount of work or expectations from others, which may impact a person’s ability to perform at an effective level (Nayak, 2014).

Another source of stress for teachers is the parents they work with as part of a child’s educational team. Specifically, Stoeber and Rennert (2008) found that teachers often strived for perfection because of student parents in their class. Striving for perfection added stress and was associated with exhaustion and burnout. Furthermore, the amount of parental support teachers receive can also influence their level of stress and anxiety (Stoeber & Rennert, 2008; Blasé, Blasé, & Du, 2008). Blasé et. Al. (2008) noted parents who are viewed a most supportive of teaching and the educational environment, and are highly involved in their child’s education, are also viewed as the ones who cause the most stress for teachers. These same parents are viewed as holding teachers most accountable for their child’s education. Similarly, Stoeber and Rennert found that parents on the other end of the spectrum, who are not involved in their child’s education and are difficult to engage in the educational process, also cause teachers to feel anxiety and put more pressure on themselves. Teachers want to help the children of these parents to see the value and importance of the educational process and put more demands and expectations on themselves in the parents’ absence.

The classroom and school environment can influence teacher and instructional support staff stress, anxiety and a low sense of comfort level in a variety of ways. Within the classroom environment, student behavior has been found to be a primary source of staff teacher stress and anxiety (Bottiani, Bradshaw, Rosenberg, Hershfeldt, Pell, & Debnam, 2012). Both Nathaniel, Pendergast, Segool, Saeki, and Ryan (2016) and Bottiani et al. (2012) found that disruptive student behavior had a positive association with teacher stress and burnout; however, this association decreased when adequate resources were available and leadership provided personalized support.

In the school environment, Nathaniel et al. (2016) and Ryan, Nathaniel, Pendergast, Saeki, Segool and Schwing (2017) found required testing to be a significant contributor to staff stress and anxiety. Specially, Ryan et al. (2017) states that the use of test-based accountability systems in public school directly correlated to higher stress and anxiety rates. This stress also was reported to have led to higher rates of attrition within the teaching profession. In addition to required testing, Nathaniel et al. (2016) found the student population and the leadership qualities and abilities to contribute to staff stress. Staff who reported high amounts of pressure and low amounts of support from school administrators showed a high rate of attrition.

Schools with low socio-economic statuses had staff report a decrease in resources which reportedly contributed to their stress levels. Nathaniel et al. (2016) and Bottiani et al. (2012) saw teachers with high levels of stress and anxiety directly affecting other teachers’ mental well-being. Stress and anxiety will often lead to disagreements between teachers or if individual goals do not align with group goals. To the contrary, these researchers found other teachers in the school environment may positively impact others teachers by creating a sense of job satisfaction and support among teachers. Beyond peers, the school environment itself may include contributing factors to staff mental health including whether staff feel safe in the school environment. Mathews, Streit and Smith (2020) noted most recently the school environment has varied levels of concern of catching COVID-19 and this is a major concern for states, districts and stakeholders.

Considering the alarming rise in the levels of stress and anxiety among teachers and associated negative outcomes among educators and students, it is crucial that school administrations employ effective strategies for reducing occupational stress among teachers (Hagermoser Sanetti et al., 2021). The most frequent negative impacts of the teacher stress are low retention rates, decreased physical and mental well-being among teachers, and increased occurrence of teacher-teacher and teacher-student conflicting situations (Nathaniel et al., 2016). A recent systematic literature review conducted by Hagermoser Sanetti et al. (2021) demonstrated that the most common interventions to reduce stress among teachers are based on mindfulness and meditation. While these techniques demonstrated significant effectiveness for reducing stress among teachers, Hagermoser Sanetti et al. (2021) suggested that further research should be conducted that explores new theories and approaches to reducing stress.

While there is evidence that mindfulness-based interventions have a positive impact on teachers’ emotional and psychological well-being, the results of empirical research were not homogeneous. In particular, research demonstrates that long-term mindfulness interventions may have iatrogenic effects on teachers (Taylor et al., 2021) The central reason for the mixed effect of long-term interventions on prevention of stress among teachers is the increased workload on teachers (Taylor et al., 2021). Teachers participate in the mindfulness programs in their free time, which decreases their ability to maintain work-life balance. According to Chitra (2020), lack of work-life balance was one of the central contributors to occupational stress among teachers. Thus, long-term participation in mindfulness programs may negatively affect the level stress among teachers.

Reiser and McCarthy (2018) conducted a mixed-method quasi-experimental research that explored the effect of an eight-week mindfulness program for prevention of stress among educators in schools. The qualitative results supported the hypothesis that mindfulness programs improve the ability of teachers to manage stress (Reiser & McCarthy, 2018). However, quantitative results did not support the hypothesis and suggested that the mindfulness practices training sessions had no significant effect on stress levels among teachers (Reiser & McCarthy, 2018). Taylor et al. (2021) conducted a research using a shorter intervention, that included only six hours of training during four sessions. The results of the research demonstrated that the brief mindfulness intervention reduced self-reported stress, burnout, and depression symptoms among teachers (Taylor et al., 2021). The comparison of these two studies demonstrate that shorter interventions have a better effect on stress reduction among school educators.

Another approach to decreasing stress levels among teachers frequently cited by researchers is spirituality and prayers. Cook Jr. and Babyak (2019) stated that the level of occupational stress was lower among teachers with higher spirituality scores. The conclusion was drawn based on a quantitative study conducted among middle school teachers in the US (Cook Jr. & Babyak, 2019). Engagement in spirituality practices was negatively correlated with time-management stress and work-related stress among teachers (Cook Jr. & Babyak, 2019). Thus, the study suggests that promotion of spirituality among teachers can improve teachers’ ability to cope with occupational stress.

Chirico et al. (2020) conducted a pilot study that assessed the effect of a prayer intervention among teachers. The study aimed at determining if biweekly prayer sessions for half and hour had an effect on burnout symptoms, job satisfaction, and well-being. The results revealed that the treatment had a significant positive impact on the well-being of the participants, decreased burnout symptoms, and boosted job satisfaction. While these results are only preliminary, since they were based on a sample 30 Italian Christian teachers selected using non-random sampling methods, the results provide significant basis for further research on the effect of prayer on teacher well-being (Chirico et al., 2020). The results of the study by Chirico et al. (2020) suggest that spiritual interventions have a similar effect as the mindfulness-based interventions.

The effect of workplace spirituality on well-being of employees was long-established. Pawar (2016) conducted an empirical study that assessed the effect of workplace spirituality on motional well-being, psychological well-being, social well-being, and spiritual well-being. The results of the quantitative analysis revealed that workplace spirituality practices had positive effect on all four aspects of employee well-being (Pawar, 2016). While there is an established correlation between workplace spirituality and employee well-being, teachers do not practice spiritual practices frequently (Evans-Amalu et al., 2021). Even though spiritual and mindfulness practices have a similar effect in comparison with spiritual practices, teachers prefer mindfulness practices over spiritual practices (Evans-Amalu et al., 2021).

In summary, stress of the instructional staff was very high before the pandemic, and the COVID-related changes worsened the situation. Stress among teachers can be explained by numerous factors, including personal, organizational and external factors. Occupational stress among teachers has a negative effect on the teacher-student and teacher-teacher relationships, educational outcomes, and well-being of teachers. There several interventions that can be used to prevent stress among teachers, including mindfulness and spiritual practices.

Role of Teachers and Instructional Support Staff

Traditionally, education consisted of classrooms with students of similar ages and abilities sitting in rows of desks, dutifully listening and reciting what they learn. These educators were teaching all students in the same manner with the same teaching methods. Students, not teachers, were held responsible for their lack of learning. These same teachers were expected to use the exact same teaching methods that had worked for generations previous to them and were prohibited or discouraged by supervisors to make any changes to their instructional models. This method has evolved significantly through the years and educators have taken on more roles than could ever to taught in a teaching training program. Some of the skills necessary to teach are not learned practices, but instead are innate skills and character traits. In more recent times, educators are expected to change and adopt new practices that support teaching as an art and a science.

During the 20th century we saw the role of educators move from merely needing to transmit knowledge through rote methods to needing to understand the psychology of learners, different pedagogical theories and strategies with a nuanced understanding of states of cognitive development in children. As the emphasis on the emotions of learning have increased, teachers have become responsible for not just curating cognitive development, but also mental wellness. Additionally, educators have been tasked with teaching and nurturing empathy and interpersonal sensitivity. They understand the essence of education is a forged relationship between a caring, genuine and knowledgeable adult and a secure, motivated student. Individual and unique learning needs now need to be met in a multitude of ways utilizing learning styles, social and cultural background, interest and abilities. Navigating these monumental tasks, along with navigating intercultural dialogues and questions of identity and belonging have become central to the work of educators. The most successful educators will have created passionate learners who feel their learning is a shared responsibility. They know engagement is only present when the learning relates to real life and the assessment of the learning process needs to be meaningful and an integral part of the student’s learning.

Establishing the classroom climate (Goddard, Hoy & Hoy, 2004) and developing rapport with students is the core of the instructional staffs’ work (Goodenow, 1993). In addition to the instructional role of the teacher, the relationship between the teacher and the students is important because it also creates the culture and climate of the classroom and lays the foundation for future academic success. In fact, Trickett and Moos (1973) identified relationships as one of the top three variables that influence classroom culture. Without stable and positive relationships, a child’s lack of secure attachments can manifest in the classroom as a host of behavioral problems that can hinder their academic and social growth (Jensen, 2010).

Many of the classroom behaviors labeled and punished as infractions of rules, are actually the result of problems with the interpersonal relationship between the teacher and the students and how they relate to one another (Sheets, 1994). According to Hughes, Luo, Kwok and Lyod (2008), the teacher’s behavior can also have an impact on student behavior. The teacher’s dispositions, coupled with classroom management skills can result in an increase in academic engagement and achievement and a decrease in problem behaviors (Soodak, 2003; Soodak & McCharty, 2006), enabling the teacher to meet the needs of all students more effectively.

Hamre & Pianta (2005) state “research on the nature and quality of early schooling experiences provides emerging evidence that classroom environments and teacher behaviors are associated in a positive “value-added” sense with student outcomes” (p. 952). It is the teachers who go beyond expectations to create an open and trusting classroom environment, who are able to generate positive student exchanges, and enhance student engagement in learning (LaGuardia & Ryan, 2002). These teachers also demonstrate nurturing teacher attributes, as they support the development of positive teacher-student relationships (Martin & Dowson, 2009), resulting in a positive classroom environment with improved academic achievement and affective outcomes such as motivation, self-concept, and academic engagement (Fraser & Walberg, 1991).

Emotionally supportive interactions have also been associated with a students’ positive growth in reading and math skills (Pianta, Belsky, Vandergrift, Houts, Morrison & NICHD, 2008) as well as social competence (Mashburn, Pianta, Hamre, Downer, Barbarin, Bryant, Buchina, Early & Howes, 2008).

Supportive teacher relationships, characterized by warmth and open communication (Pianta, 1992), are associated with greater academic performance and engagement (Hughes et al., 2008), and performance (McCartney, 2007). The supportive relationships with the teacher provide a “secure base” that allows children to explore and take risks in their learning, and develop social and cognitive skills (Ainsworth, Belhar, Waters & Wall, 1978; Brock, Nishinda, Chiong, Grim & Rimm-Kauffman, 2008). Therefore, when teachers establish a safe and positive learning environment where students feel supported, student motivation increases, and performance improves (Turner & Patrick, 2004).

The teacher also has the ability to shape the students’ thinking skills through positive and purposeful interactions. Cazden (2001) suggests that the teacher-student relationship is one of the most significant factors in the learning environment. The quality of the teacher-student relationships in the classroom is a predictor of the students’ academic engagement (Furrer & Skinner, 2003) and motivation. Teacher-student interactions can awaken a variety of developmental processes (Vygotsky, 1978) for academic achievement. When teachers develop a supportive classroom community, students are imparted with a sense belonging, their social anxieties and frustrations are alleviated, and students are more motivated to comply with the teacher’s requests and act appropriately with their peers (Elias & Schwab, 2006). Theories of motivation suggest that students are more likely to engage in learning when teachers are thoughtful, approachable, and sensitive (Hamre & Pianta, 2005). Having a caring relationship with an adult is also a protective factor associated with resilience and the development of pro-social competencies that promote learning (Masten, 1994). As a result, a positive teacher-student relationship has a high correlation to student achievement (Osterman, 2000) and plays a critical role in the development of school readiness skills (Pianta et al., 2008), which students need throughout their school career. Additional research findings also support the premise that social and emotional support from teachers may be equally impactful to the academic development of students, as is the use of specific instructional techniques (Hamre & Pianta, 2005).

During the early 21st century, educators saw the introduction of technologies in learning and had to begin to learn alongside their students to keep up with rapidly changing web-platforms and devices. This learning curve was only exacerbated by the COVID19 pandemic. The unprecedented challenges for educator has created significantly more challenges for educators. The added responsibility to become an expert in technology has been draining on teachers and the increase in technology usage has made their role of building relationships that much more difficult.

Role of School Leaders Supporting Teacher and Instructional Support Staff Well-Being

School leaders should help their employees learn to deal with stress. Kamery (2004) noted that companies can take five steps to curb excessive pressure on the job:

- Leaders must carefully examine whether restructuring is in the best interest of the business and its employees. Downsizing often leaves the remaining employees with too many tasks for one individual to accomplish.

- Leaders should re-examine employee workloads to determine if the organization has reasonable expectations the various job positions.

- Leaders must allow employees to be creative. Many employees feel that their talents are not being used to their full potential.

- Leaders must encourage employees to clarify and/or create their own goals. Research indications that employees who could not verbalize their goals are more affected by stress in the workplace.

- Leaders must encourage, and provide opportunities for, continued learning. Learning stimulates the mind and keeps employees on a path for future contributions to the organization.

Researchers have found that positive relationships in the workplace can facilitate employee-learning by helping workers feel safe to take the risks that are an inherent part of the learning process. Those positive relationships are built from school leaders leading by example. Baker, Terry, Bridger and Winsor (1997) pointed out that positive working relationships go beyond surface level friendliness and are in fact, based in deep trust and respect. They found one resoundingly clear method to creating the necessary positive relationships for teacher success: model, model, model. Seligman, Ernst, Gillham, Reivich & Linkins (2009) found a specific approach for leaders to use to support staff who report a high level of work-related stress. The model nurtures a sense of well-being, fulfillment and purpose. Research has shown that when all elements of this model are used consistently, improvements are made to physical health, vitality, job satisfaction and commitment within organizations (Alder, Allen & Meyer, 2011). The five elements of Seligman, et al.’s approach are: positive emotions, engagement, positive relationships, meaning and accomplishments. Similar to other studies, Seligman et al. (2009) states that teachers need to be supported to achieve intrinsic goals, have their self-esteem boosted and have their sense of pride supported.

While the impact of COVID-19 is still being felt by schools, Seligman et al.’s model encourages school leaders to support staff in living more meaningfully, connecting with a supportive community, taking more part in activities that feel good, and accomplishing intrinsic goals to allow themselves to be fully engaged with life, including their work (Seligman et al. 2009).

Research related to the role of school leaders in supporting staff well-being is limited. Much of the literature supports school leaders supporting the needs of the school and teaching and learning. The COVID-19 pandemic has brought to light the need for further research.

Employee Assistance Programs

Employee assistant programs (EAPs) are defined as job-based programs operating within a work organization for the purposes of identifying “troubled employees,” motivating to resolve their troubles, and providing access to counseling or treatment for those employees who need these services. The term troubled employee refers to those individuals whose personal problems (ie. alcoholism, drug addiction, marital difficulties and emotional distress) preoccupy them to the extent that in either their own or their supervisor’s judgement, their work is disrupted. The word troubled is used for several reasons, but most often due to it being historically consistent with the term employee assistance and the fact that is appropriately describes persons as being chronically troubled by their problems.

Data from national surveys reported by Roman (1983) and from a field study by Trice and Beyer (1984), using both quantitative and qualitative methods indicate that employers concerned about their employees’ welfare and those concerned about their social responsibility to the community are more likely to adopt EAPs that employers who do not express these sentiments. Simply stated, programs are adopted because employers believe that helping employees to solve their personal problems is good business and demonstrates social responsibility.

In recent years, the importance of EAPs has grown considerably due to increased prevalence of mental heath disorders in the US. Attridge (2019) reported that the prevalence of anxiety disorders among employees was 5.7%, around 7.6% had depression or mood disorders, 6.4% had substance or alcohol misuse, and up to 3% of employees were known to have problems with illicit drug use. Statistics demonstrates that more than 20% of working Americans have at least one of the disorders mentioned above. As a result, more than 1,500 studies were published on the effectiveness of EAP for addressing the mental health problems of the employees.

Shain & Groeneveld (1980) suggest companies adopt employee assistance programs because they are cost effective. Although the cost effectiveness can be difficult to predict, a number of recent methods for analyzing programs costs and benefits have been developed. Trice (1980) has shown the most common method of evaluation was to compare employee performance prior to treatment with performance after treatment and to assign a dollar value to it. This was only effective when looking at drug and alcohol treatment programs.

Various models for EAP adoption in schools have been considered and researched extensively. EAPs in school districts are often set up to help their teachers and support staff resolve personal problems so they can maintain or return to a proficient level of job performance. One model that is used by very large districts has the district employee acting as the EAP (Blum, Roman & Patrick, 1990). This person’s sole job is to assess the problems of district employees and refer them to outside providers for appropriate supports and services. The positive aspects of this model are the communication and ownership within the district. Having a district-employed person as the troubled employees initial contact, helps them to see directly how their organization is supporting their basic needs. The employee is able to add a personal touch to process and as a community member will be familiar with local supports and services and can be kept abreast of new services as they become available within the community (Blum, et al, 1990). This can allow for timely communication with employees who are not seeking active help. Finally, the biggest strength to this type of EAP model is the ability to act in moments of crisis. The district employee is more readily available than an outside agency and can support a troubled employee in facilitating their communication with district supervisors in times of crisis.

The costs incurred for the recommended supports and services are typically picked up by the employee’s insurance carrier, which is a negative compared to other EAP models. Another negative of this model is some employees may view this model as lacking in confidentiality. They may view the only way they can receive help and support is by speaking with a peer which may make them uncomfortable. As most EAP supports all levels of district employees, depending on the classification of the EAP Coordinator, there may be times when a troubled employee would actually be assessed by a subordinate, creating an even more uncomfortable situation.

A second type of model for EAPs in schools is hiring an outside provider for all EAP services (Blum, et al., 1990). Under this model, the initial assessments, some free services and appropriate feedback are provided to all district employees. Under this model, the district does not pay an employee to act as the EAP, as in the aforementioned model, but does pay a certain amount annually for each district employee whether they seek services or not. This model can be cost effective for schools and employees and the contract with an outside EAP agency is often significantly less than employing a full-time employee for this service.

Many mental health agencies work with EAPs to provide contracts for some services to be paid for in full up to a certain dollar amount. This model allows for a high level of confidentiality for the troubled employee. The employee is contacting a third party and the only communication that occurs back to the district is a non-descript number associated with the employee and broad details on the recommended outcome of the initial assessment. Since the third-party EAP contracted agency is outside of the district, employees are more apt to trust the confidentiality of the process than they would with a school district person. The disadvantages for this type of EAP model are the district may be less likely to market the services and encourage employees to utilize the service simply because they are unfamiliar and there is no district ownership to the service (Blum, et al., 1990). Additionally, the lack of close relationships between outside agencies and employee supervisors can decrease the likelihood for early problem identification (Blum et al., 1990; Finch & Phillips, 2005).

Today, the majority of EAPs are delivered by outside providers rather than a hired mental health professional (Roche et al., 2018). These providers are usually for-profit organizations that provide services in the sphere of relationship, mental health, and trauma counseling (Roche et al., 2018). A typical intervention a series of four or five counselling sessions that take place at work (Roche et al., 2018). While the sessions prove to be effective for some conditions, they have a limited effect on others (Roche et al., 2018). For instance, a recent study by Nunes et al. (2018) reported that while EAPs have a positive effect on employees with depression and anxiety by reducing their symptoms, these programs have low or no effect on non-risk drinking habits. Moreover, EAPs reduce absenteeism by decreasing the level of sick leave from moderate to low (Nunes et al., 2018).

The effectiveness of a program depends on its characteristics and strategies employed by the mental health professionals. While traditional behavioral interventions and psychotherapy proved their effectiveness in improving the mental health conditions of the employees, alternative approaches have also proved their effectiveness. For instance, Van Wyk and Terblanche (2018) reported that including spirituality as a central characteristic of EAP proved to be effective for addressing mental health problems of employees. Spirituality is a major characteristic of a well-known twelve-step program that is commonly used for helping people with substance abuse disorders (Van Wyk and Terblanche, 2018). Thus, including spirituality as the central characteristic of a program can be helpful for achieving the desired results. Moreover, the clients usually see spirituality as a positive characteristic of EAP, which improves the outcomes (Van Wyk and Terblanche, 2018).

Even though every employee may have similar opportunities to receive access to EAPs, not everyone is equally likely to use the opportunity. Milot (2019) reported that perceived stigma from the program is a common cause for avoidance of participation in EAPs. The research also demonstrates that the higher the stigma received from the mental illness, the higher the perceived stigma from the program (Milot, 2019). As a result, the employees that need EAPs the most are less likely to use them due to perceived stigma. Therefore, it is crucial for the employers to spread awareness about the level of stigma from the program to ensure that EAPs meet their audience.

Clouser, Nation and Hyde (2021) found that using a wide range of indicators to evaluate job performance is the most effective way to determine cost-benefit analysis for employee assistance programs. These indicators include: number of days absent, number of on-the-job and off-the-job accidents, number of discipline and grievance procedures, amount of insurance premiums and amount of work completed. Similarly, Finch and Phillips (2005), found the most effective way to ensure the success and productivity of an EAP is to provide frequent evaluations of the program. This can be a daunting task when working with an agency that ensure anonymity and when contracts do not include communication clauses. EAP agencies can be selective in what information they provide to employers making it difficult for employers to evaluate these programs. Previous studies have showed significant benefits, which have been attributed to the success of these programs and further research to determine their effectiveness post COVID19 is needed (Clouser et al. 2021).

A recent systematic analysis of literature concerning the effectiveness of EAPs demonstrated that its benefits for the company are questionable (Joseph et al., 2018). In particular, assessment of results of 17 rigorous studies revealed that EAPs have a varying effect on absenteeism (Joseph et al., 2018). In other words, while EAPs may provide benefits to the employees’ mental health, there is no evidence that the reduce absenteeism. Moreover, the systematic analysis of quantitative studies provided no significant evidence that EAPs increase workplace productivity (Joseph et al., 2018). However, there is evidence that EAPs increase presenteeism among employees (Joseph et al., 2018). Considering the suggestions by Clouser et al. (2021), the findings of the research by Joseph et al. (2018) may be skewed. Therefore, it is recommended that the organizations conduct a cost-benefit analysis before implementing EAPs.

Occupational Wellness Programs

According to the Centers for Disease Control (2013), workplace wellness programs are designed to promote physical and mental health and well-being in the workplace. Workplace health promotion programs have their roots in the socioecological model of health, which spans the individual, family, workplace, community and larger environment and health advocacy to create and impact public health policy at the organizational, local and regional levels. These programs can improve physical, psychological, educational and work outcomes for individuals and help control or reduce overall health care costs by emphasizing prevention of health problems, promoting healthy lifestyles, improving individual compliance with occupational safety and health regulations, and facilitating access to health services and care. Such programs play a role in creating healthier workers and workplaces but also healthier families and communities. Workplace health promotion programs contribute to an environment that supports and promotes the health of individual employees and the overall public. These programs take advantage of their pivotal position in people’s jobs and places of employment to provide individuals employees, as well as their family members, with the knowledge and skills they need to make informed decisions about their life. They foster good health, work performance, work quality and quality of life (Ferman, Allensworth & Auld, 2010).

Workplace health promotion programs area a coordinated and comprehensive set of health promotion and protection strategies implemented in the workplace; these strategies include programs, policies, and benefits as well as safety, health and environmental supports system designed to encourage the health and safety of all employees and their families. Workplace health promotion programs involve (Centers for Disease Control, 2013):

- Having an organizational commitment to improving the health of the workforce;

- Providing employees with appropriate information and establishing comprehensive communication strategies;

- Involving employees in decision-making processes;

- Developing a working culture that is based on partnership;

- Organizing work tasks and processes so that they contribute to, rather than damage, health;

- Implementing policies and practices that enhance employee health by making the healthy choices the easy choices and;

- Recognizing that organizations have an impact on people that is not always conducive their health and well-being.

The federal government’s Healthy People Initiative (U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, 2000) proposed a definition of comprehensive work place health promotion programs as those that incorporated five key elements: (1) health education (i.e., skills development and lifestyle behavior change, along with information dissemination and awareness building), (2) supportive social and physical work environment (i.e., support of healthy behaviors and implementation of policies promoting health and reducing risk of linkage (i.e., connecting to related programs such as employee assistance programs), and (5) worksite screening and education (i.e., programs linked to appropriate medical care) (Soto Mas, Allensworth & Carnara, 2010).

Workplace wellness programs address occupational health and safety, organization conditions of work, leave policies and benefits, and workplace wellness initiatives that are integrated to maximize resources and ensure success. The most promising programs feature a strong employer commitment and are responsive to employees’ needs. The workplace is viewed as a health-promoting environment that connects employee health and the health of the organization, community, and society (Polanyi, Frank, Shannon, Sullivan & Lavis, 2000). The most effective programs feature advocacy strategies that create and impact health policy at the workplace, community, regional, state and national levels (Ferman, Allensworth & Auld, 2010).

Finally, workplace health promotion programs are part of strategic human resource management: integrating strategies and systems to achieve an overall mission to ensure the success of an organization while meeting the needs of the organization’s clients, customers, consumers and other stakeholders as well as the employees (Polanyi et al., 2000).

Workplace wellness programs have evolved over the years and most recently have begun to focus on detriments of health in the occupational setting (Polanyi et al., 2000). Although genes, behavior and medical care play a role in how well we feel and how long we live, such factors as economics, social conditions and the culture in which we are born, live, learn, work and play have the most significant impact on out mental and physical health. These are called determinants of health. Differences, or disparities, in health status in the workplace and wider community results from the determinants (Soto Mas, et al., 2010). Disparities occur in physical health (e.g., higher rates of obesity, asthma, tooth decay, sexually transmitted diseases), mental health (e.g., higher rates of depression, anxiety, stress, substance abuse), and built environments (e.g., higher rates of violence, crime, inadequate housing, recreation facilities). In the workplace, health determinants are categorized as originating in the job itself (job strain, fatigue, anxiety, depression, musculoskeletal disorders and physical illness), the organization (remuneration, benefits, and workplace participation in decision making), and society at large (gender, economics, education, disability, geographic location, culture, ethnicity, social conditions and sexual orientation) (Polanyi et al., 2000; Soto Mas et al., 2010).

Occupational wellness programs can be considered controversial. Employers believe that they improve health, reduce absenteeism and cut the cost of employee health benefit programs. They are encouraged int his belief by health promotion program vendors, who aggressively tout the benefits of their programs. Disability advocates express concern that workplace health promotion programs are perpetuating discrimination against the disables and health status underwriting. Privacy advocates worry about who has access to the sensitive medical information that some programs demand of participants. Other worry about the control that employers assert over their employees’ lives through these programs, as employees will spend off-the-clock hours every week trying to meet the demands of the program (Linnan, Bowling, Childress, Lindsay, Blakey, Pronk, …Royall, 2008).

Although there are pros and cons to occupational wellness programs, numerous studies have found the positives outweigh the negatives. In a 2004 survey conducted by the Office of Disease Prevention and Health Promotions, employers whose health promotion programs were comprehensive and included these five best practice elements were most meaningful and sustainable: health education; links to related employee services; supportive physical and social environments for health improvement; integration of health promotion into the organization’s culture; and employee screenings with adequate treatment and follow-up (Linnan et al., 2008).

Workplace health promotion programs are a powerful tool for improving the health and well-being of individuals and communities. The most promising programs feature a strong employer commitment and are responsive to employee’s needs. The workplace is viewed as a health promoting environment that connects employee health and the health of the organization, community and society (Soto Mas et al., 2010).

Saliba and Barden (2017) stated that occupational wellness programs have become essential for numerous employers, as they promote physical and mental health of employees. The most common wellness programs aim at reducing stress, acquiring healthy habits, and promote physical exercises (Saliba & Barden, 2017). Research demonstrate that the effectiveness of such programs depends on their alignment with the needs of the employees (Saliba & Barden, 2017). If aligned with the needs of the employees, occupational wellness programs improve workplace satisfaction, reduce stress, and improve retention rates (Varga et al., 2021). This implies, that not only do the occupational wellness programs add to the overall effectiveness of the employees, such programs may reduce HR costs associated with hiring and training new staff due to increased retention rates.

Summary

Occupational stress is a significant bother for workers, employers, and the healthcare system of the US. More than 65% of stress experienced by US citizens is attributed to occupational stress (Saliba & Barden, 2017). Teachers are also known to experience large amounts of stress in the workplace. Many studies have reviewed and investigated a wide variety of potential variables that impact teacher and school staff stress levels; however, few have looked at COVID-19 stress and anxiety and how it has directly impacted school staff (Mathews et al., 2020).

Teacher have become frontline workers during the COVID-19 pandemic when schools reopened in Fall 2020 with varying levels of face to face and virtual instruction. Occupational stressors for teachers and other instruction staff in schools have a negative impact on a far greater impact than just on the employees themselves. Student success and achievement, school climate and school culture can all be impacted by instructional staff experiencing a high level of stress related to their daily responsibilities. Many studies have shown a relationship to teacher stress being associated with more significant behavior challenges and less positive teacher-student relationships (Clunies-Ross, Little, & Kienhuis, 2008). Similarly, less positive teacher-student relationships are linked to low student achievement. These two trends are catalysts for a cycle that contributes to the stress levels of all instructional staff.

There are numerous strategies employers can use to reduce stress. First, employers can design interventions that can help teachers cope with stress based on spirituality or mindfulness. Second, employers can train the leaders to provide support to the general staff to reduce stress. Third, employers can maintain workplace culture that promotes emotional support among employees to each other. Fourth, organizations can establish employee assistance programs to help the teachers cope with their mental or physical health conditions. Finally, occupational wellness programs may be introduced to help the employees maintain a healthy lifestyle.

Based on the numerous studies conducted on occupational stress in general it can be concluded that stress in the workplace is an emerging epidemic and has become a serious concern to occupational doctors, employers, as well as the public. Huge impact can be seen on workforce performance of the organization and cost incurred to the organization and outside agencies, as well.

Methodology

The literature related to the enhanced working environment when employee wellness offerings are made is abundant. Additionally, literature outlining the need for employers to focus on their occupational wellness in order for businesses to succeed is equally plentiful. Occupational wellness is the ability to achieve a balance between work and leisure time, addressing workplace stress and building relationships with coworkers. At the center of occupational wellness is the premise that occupational development is related to one’s attitude about one’s work. In schools, the need for staff to be well, and make their own wellness a priority, is of significant need. When teachers and staff feel supported, empowered and trusted by school leadership, they are able to create conditions that lead to students’ academic, social and emotional development. However, as the demands on educators increase, districts continue to face challenges like teacher burnout, low teacher retention and high turnover rates. In 2017, the American Federation of Teachers’ Quality of Work Life survey found that more than three out of every four educators “often” or “always” feel stressed at work, twice the rate of other workers. Similarly, since reopening schools, following the outbreak of COVID-19, teachers have returned to classrooms with new teaching responsibilities, new safety concerns and new student needs. In a survey conducted in March 2021 by the Center for the Developing Child at Harvard University, the most reported feeling by teachers in the work environment was anxiety. Teachers are expected to manage their own well-being, model healthy living for their students and be successful in achieving the standards of their jobs. Teacher wellness has a significant impact on school climate, student learning, and student social emotional development. Yet teacher stress and burnout continue to present retention and turnover challenges in districts: 85 percent of teachers have reported that their work-life imbalance affects their ability to teach (Podolsky, Kin, Bishop, & Darling-Hammond, 2016). More than one in five new teachers leave the profession within their first five years of teaching—and this attrition is substantially worse in high-poverty schools (Podolsky, et. al., 2016). During the COVID-19 pandemic, teachers and staff have been managing higher levels of stress and grappling with physical health, mental health, and emotional well-being concerns.

According to Panorama Education’s User Guide for their teacher surveys (2019), elevating teacher and staff voices through surveys can help school and district leaders listen to and address educators’ professional, social and emotional needs. Educator feedback can spark productive conversations about important topics. These topics include areas such as adult well-being, capacity and efficacy around supporting students’ academic, social, and emotional learning, cultural competency and awareness, school climate, relationships, and effectiveness of school leadership.

This qualitative study was developed to gather educator perceptions of their own well-being to allow Wyomissing Area School District leaders to improve the quality of the work environment, help prevent teacher and support staff turnover, and develop targeted programs and professional development that address employee well-being and job satisfaction. The recommendations from this study will be used to prioritize supports to instructional staff to create a more positive working environment where employee well-being is evidently valued by school and district leaders.

Settings and Participants

This study took place in the Wyomissing Area School District in Berks County, Pennsylvania. The Wyomissing Area School District consists of three schools servicing approximately 1,900 students in grades K-12. The student ethnicity population is broken down as: 62.2% white or Caucasian, 25.1% Hispanic, 4.8% black or African American, 4.9% multiracial and 2.5% Asian. The American Indian, Alaska Native, Native Hawaiian and Other Pacific Islander groups are not represented by the Pennsylvania Department of Education’s annual data collection. This is due to guarding against improper statistical comparisons due to small group sizes (n=10 or less) and to protect the confidentiality of those students. The Wyomissing Area School District has 125 professional teaching positions and 46 instructional aide positions. There is currently one vacant teaching position and twelve vacant instructional aide positions. Contrary to the race and ethnicity representation of our student population, our instructional staff is 99% white or Caucasian. For the 21-22 school year, the district has experienced ten professional staff resignations. This is a high for the last three years, but in each of those three years, six or more professional staff members have resigned. The resignations of instructional aides are even higher with five of the positions remaining vacant for more than two years. The level of education of the professional teaching staff and instructional aides range from high school diplomas to doctoral degrees. Approximately 19% of the instructional staff have a high school diploma or 2-year degree, 14% have a bachelor’s degree, 64% have a master’s degree and just over 1% have a Ph.D. The professional teaching staff have remained in the district for an average of 13.87 years, and the instructional aides have remained in the district for an average of 6.33 years. The Wyomissing Area School District has seen relatively low administrative turnover over the past 5 years. The administrative team works well together and develops goals for individual buildings as well as the district as a whole.

Instructional staff, both professional and support staff, who work directly with students on academic areas of instruction were asked to participate. Instructional professional staff are defined as staff certified by the Pennsylvania Department of Education with a level I or level II teaching certification in one or more academic areas. These staff are responsible for preparing lessons and delivering direct instruction in specific academic areas. The professional staff cover all general education and special education classes to include disciplines such as English language arts, mathematics, science, social studies, music, art, technology, family and consumer sciences and foreign languages.

Instructional support staff are defined as school staff members who provide specialized instructional support as well as support to students while they utilize school facilities. School support staff play an important role in ensuring students are learning in a safe and supportive educational environment. Support staff are responsible for providing accommodations or modifications to support students with specific academic standards and/or in the learning environment. Instructional support staff can work with individual students or small groups of students to provide supports and services outlined in an IEP or they may work with whole classes in a general education environment. Instructional support staff work with students in general education and special education classes. These staff are responsible for providing a number of types of support to students. Their work is guided by the classroom teacher or special education case manager and can include clerical duties, pre-teaching and re-teaching, functional skill support, vocational training and job skill training.

One hundred twenty-four teachers and thirty-four support staff members were included in the initial email asking for participation. Of the 158 instructional staff members who were invited to participate, 53 completed the survey in its entirety.

Data Collection

Portions of two national surveys were used to develop one comprehensive survey for this project. The Wyomissing Area School District purchases medical insurance coverage from Capital Blue Cross. Capital Blue Cross supports all businesses that choose them as a provider in developing employee wellness programs. One of the ways they support their partner businesses is by providing a survey to allow employers to adequately gauge the wants and needs of employees related to their physical and mental wellness. The survey focuses on the perceived needs of an employee’s health and reviews possible motivating factors, and barriers, for participation in an employee sponsored wellness program.

To compliment the portions of the survey from Capital Blue Cross, subsections of the Panorama Teacher and Staff Survey developed by Panorama Education was also used. This survey was developed by the Panorama research team, including Dr. Hunter Gehlbach and Dr. Samual Moulton, using advanced survey methodology. Dr. Gehlbach and Dr. Moulton developed their survey instruments based on multiple modern research principals for survey design. These practices include:

- Wording survey items as questions rather than statements;

- Avoiding “agree-disagree” response options that may introduce acquiescence bias and instead using verbally labeled response options that reinforce the underlying topic;

- Asking about one idea at a time rather than using double-barreled items (e.g., “How happy and engaged are you?”); and

- Using at least five response options to capture a wider range of perceptions.

Each of these four characteristics substantially minimize measurement error for researchers. Dr. Gehlbach and Dr. Moulton’s surveys for use by Panorama Education include topics such as well-being, belonging, school climate, teacher efficacy, and staff-leadership relationships to help leadership teams identify needs and design support systems for teachers and staff. Survey questions from each topic area were chosen to support this project. Panorama Education’s survey questions are grounded in educational research and have shown over many years how teachers across all grades teach best when they feel competent and connected and avoid burnout when they feel supported and impactful (Mankin, von der Embse, Renshaw, & Ryan, 2017).

Many of the research questions allowed for responses to be recorded using a Likert scale of responses. Different phrases for the Likert scale were used throughout the survey to allow participants to provide data relating to their attitudes and the extent to which they agree or disagree with a particular question or statement. A Likert scale was chosen by the Panorama research team and Capital Blue Cross for their surveys to allow for nominal, ordinal, interval and ratio data to be retrieved from their surveys. Additionally, both research teams noted the ease of implementation for a survey with a Likert scale, allowing for quantifiable answer options and the ability to analyze the rank of opinions. For this research, it is also noted that the ease to respond to the questions with a Likert scale or multiple-choice responses is suspected to have encouraged staff to give more valuable input in the few free-response questions that were included in the survey. The free response questions were added to allow for participants to share other opinions related to their well-being needs, but were optional to complete.

The survey (Appendix A) was inputted into a google form to provide an easy and secure means for participation. The google suite is housed on the Wyomissing Area School District’s server and is protected to ensure complete security of any data inputted or retrieved from the server by school district employees. An email with a link to the survey was sent to all instructional staff in January of 2022 and a reminder email was sent in February of 2022. The email and survey fully informed staff regarding their participation being fully voluntary and that even if they started the survey, they could delete any data they inputted before pressing submit within the survey. Staff were thanked, in advance, for considering the use of their time to participate in the study. They were notified that their answers were completely anonymous and would not be attached to their google account in anyway. Finally, staff were provided with the approval dates from the California University of Pennsylvania Instructional Review Board.

Data Analysis and Methods

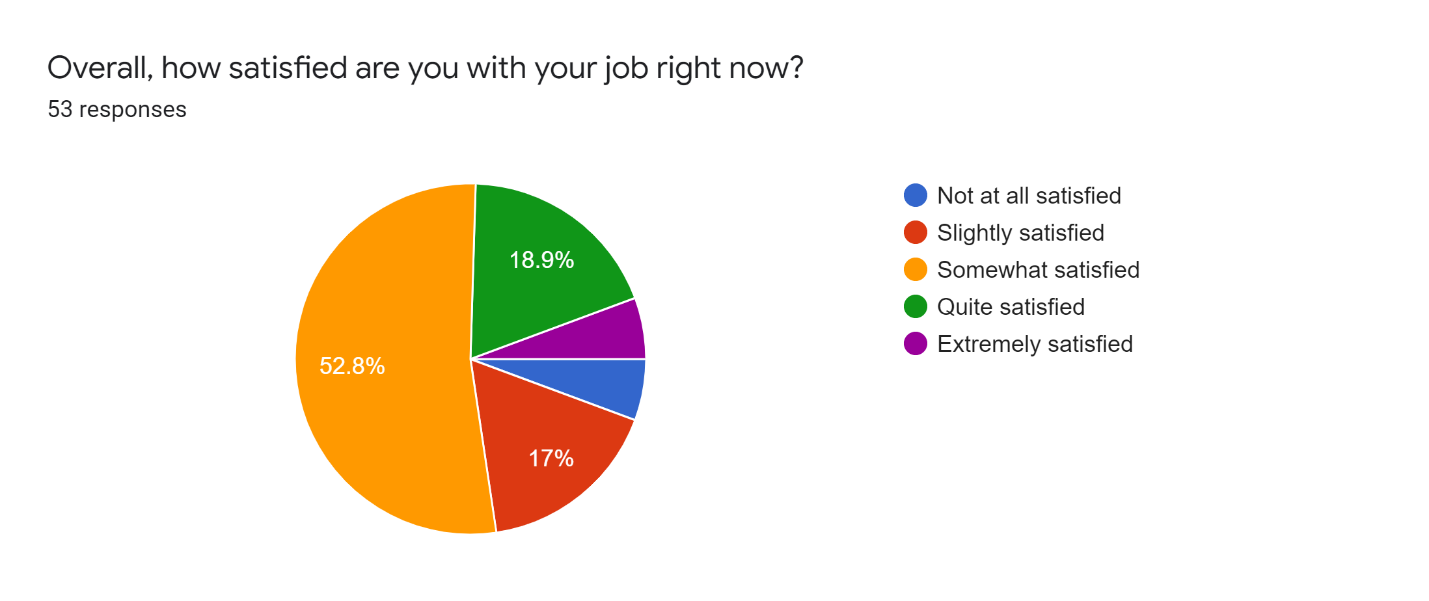

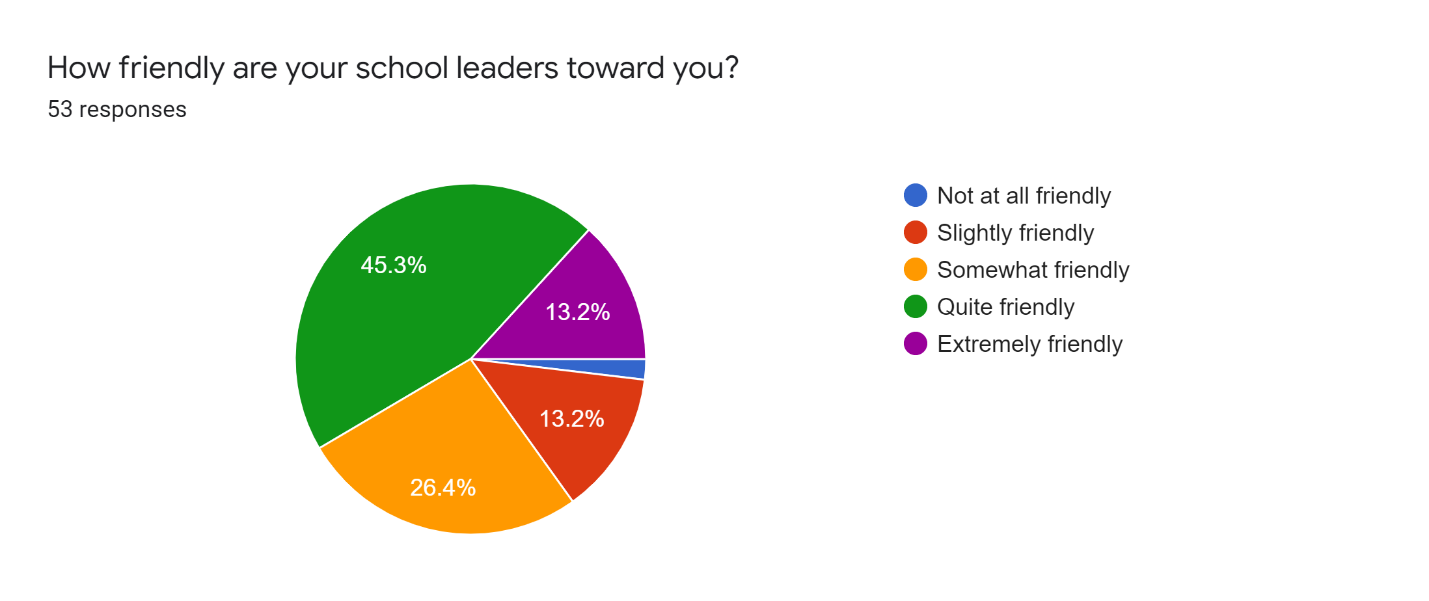

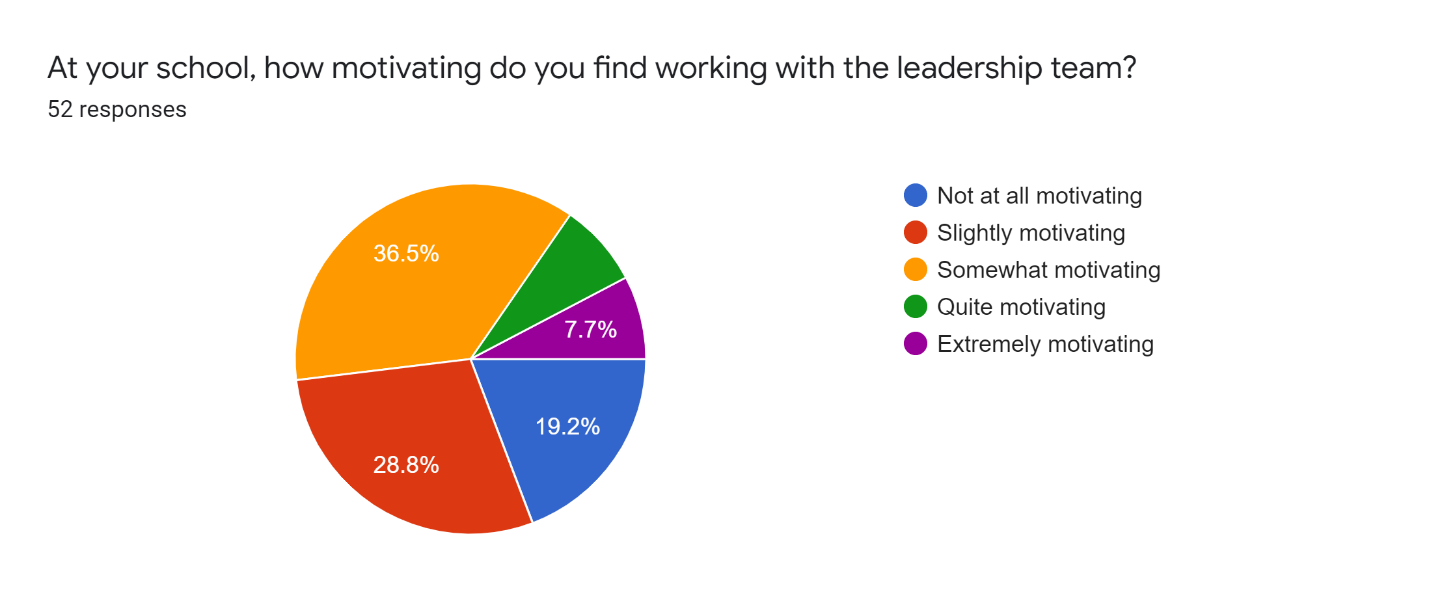

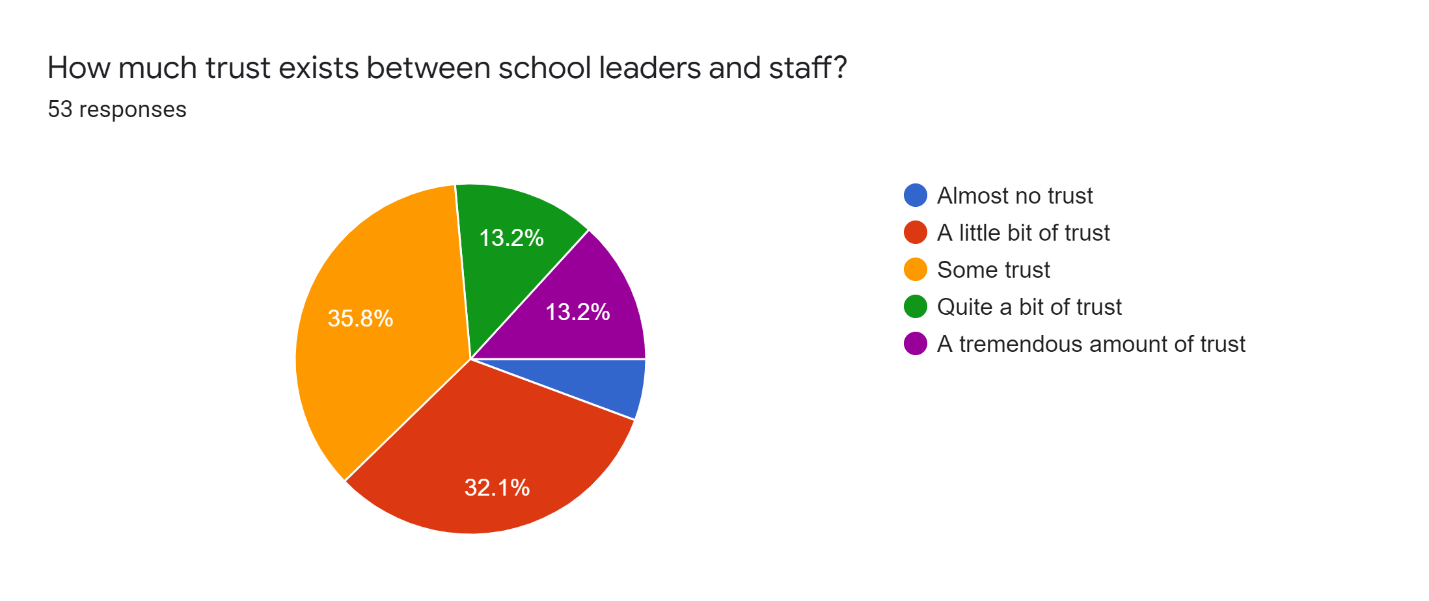

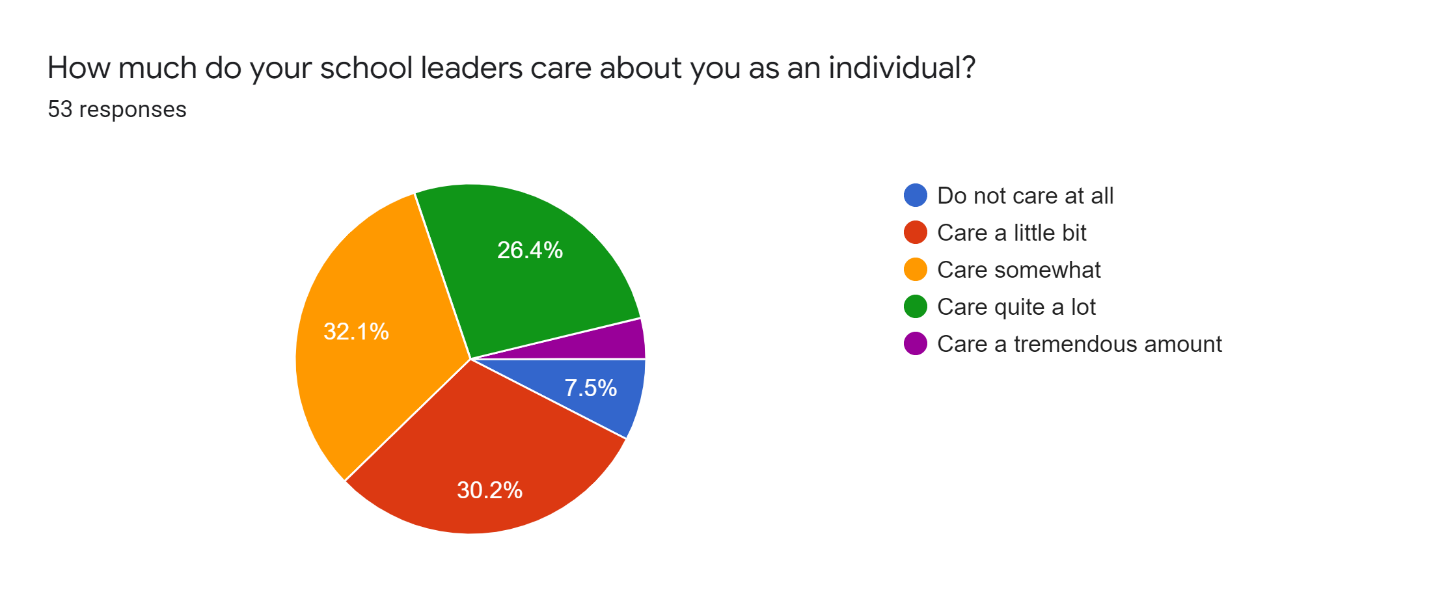

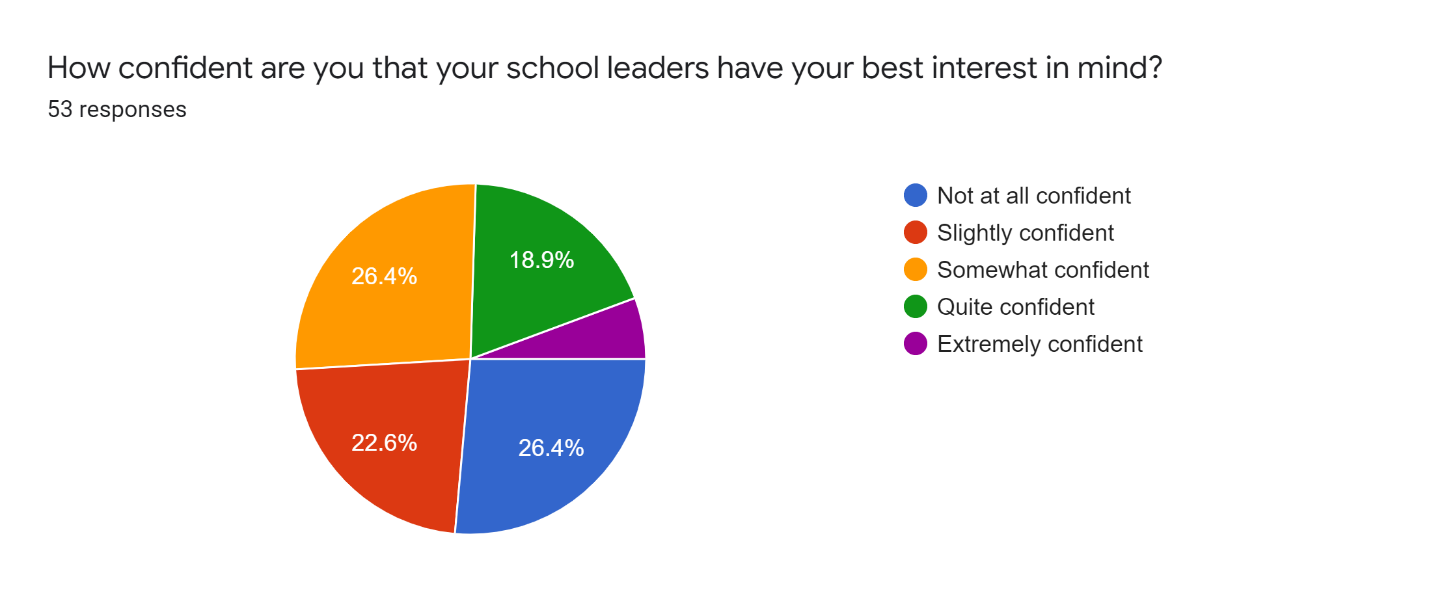

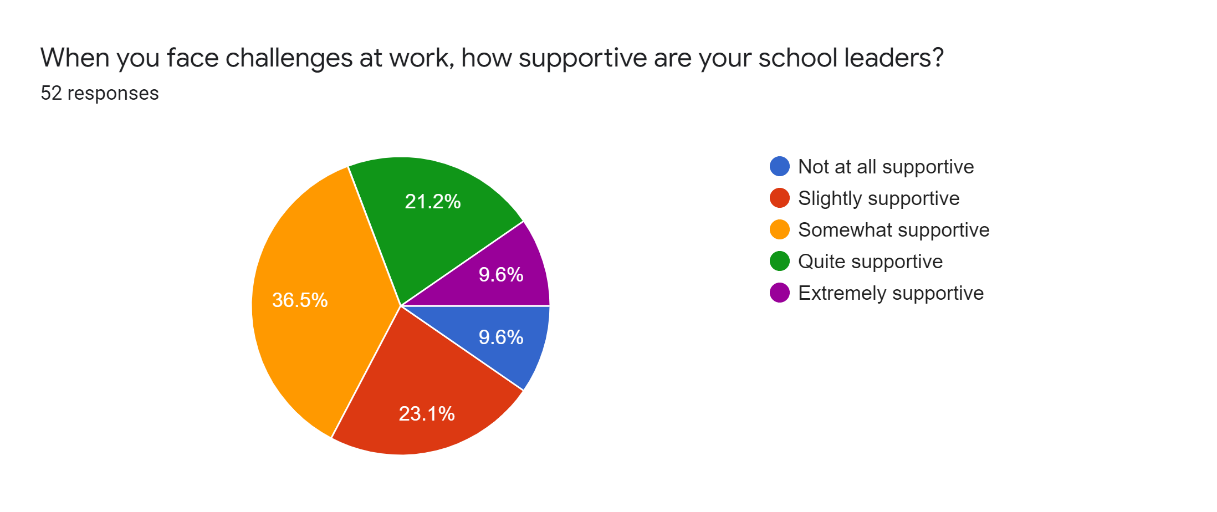

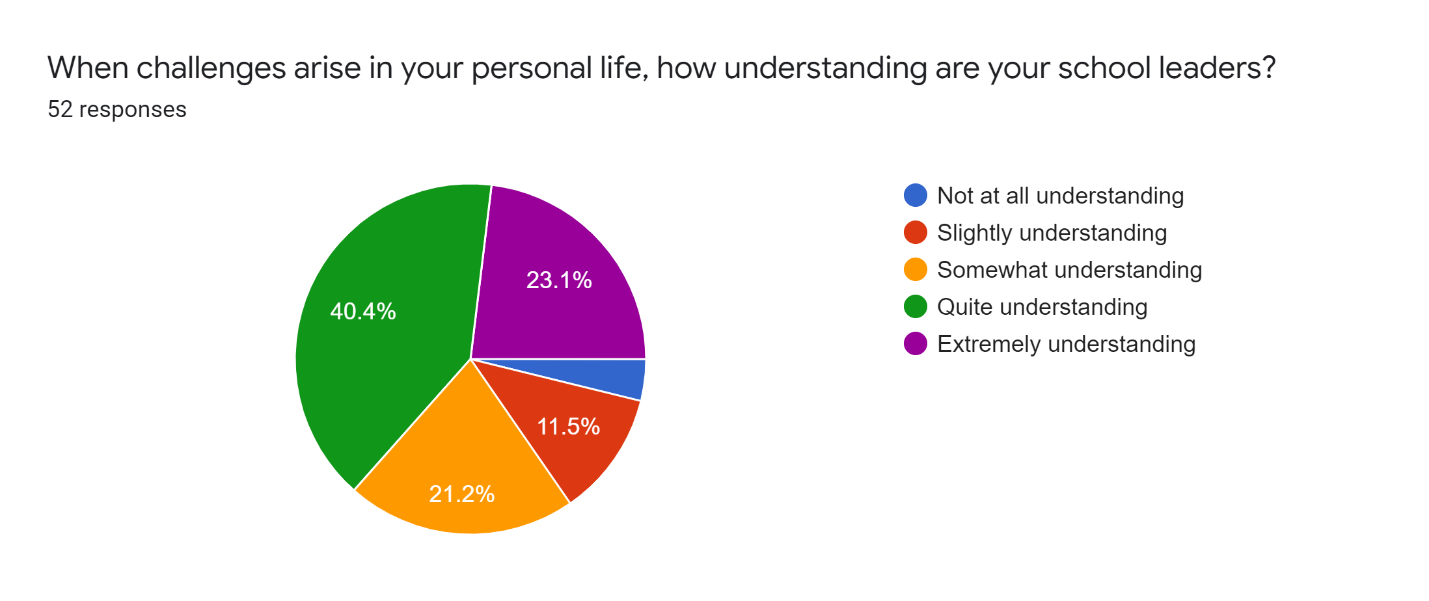

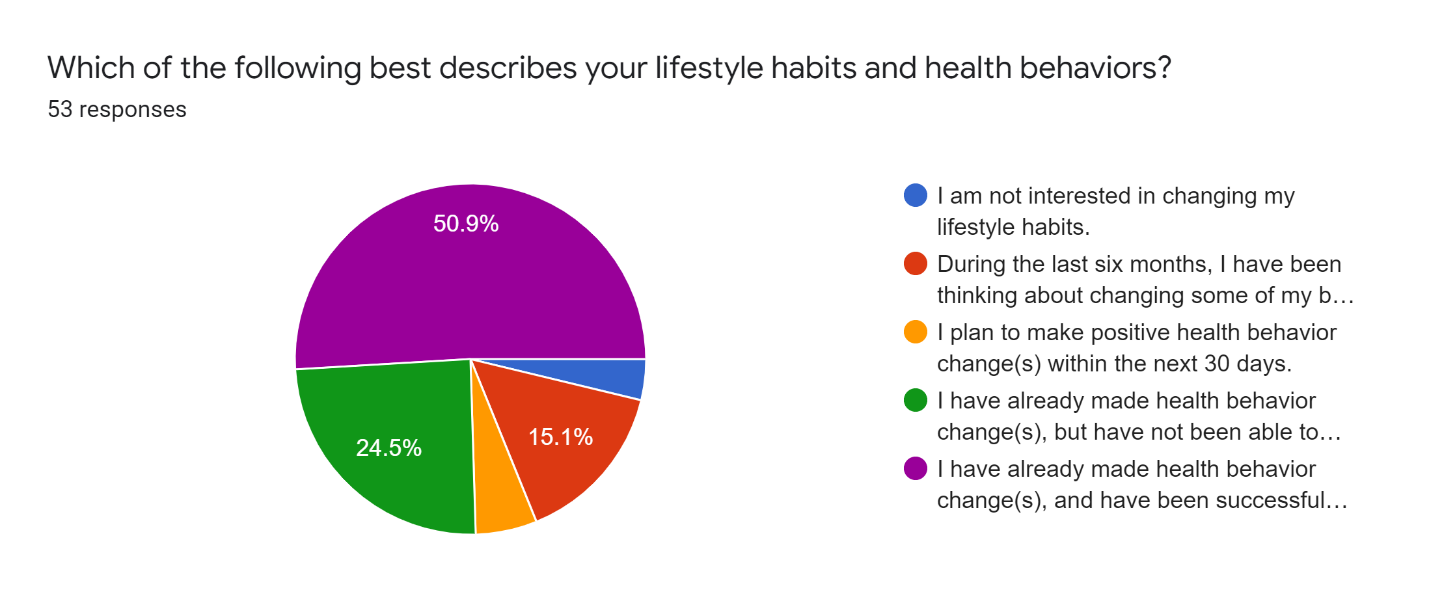

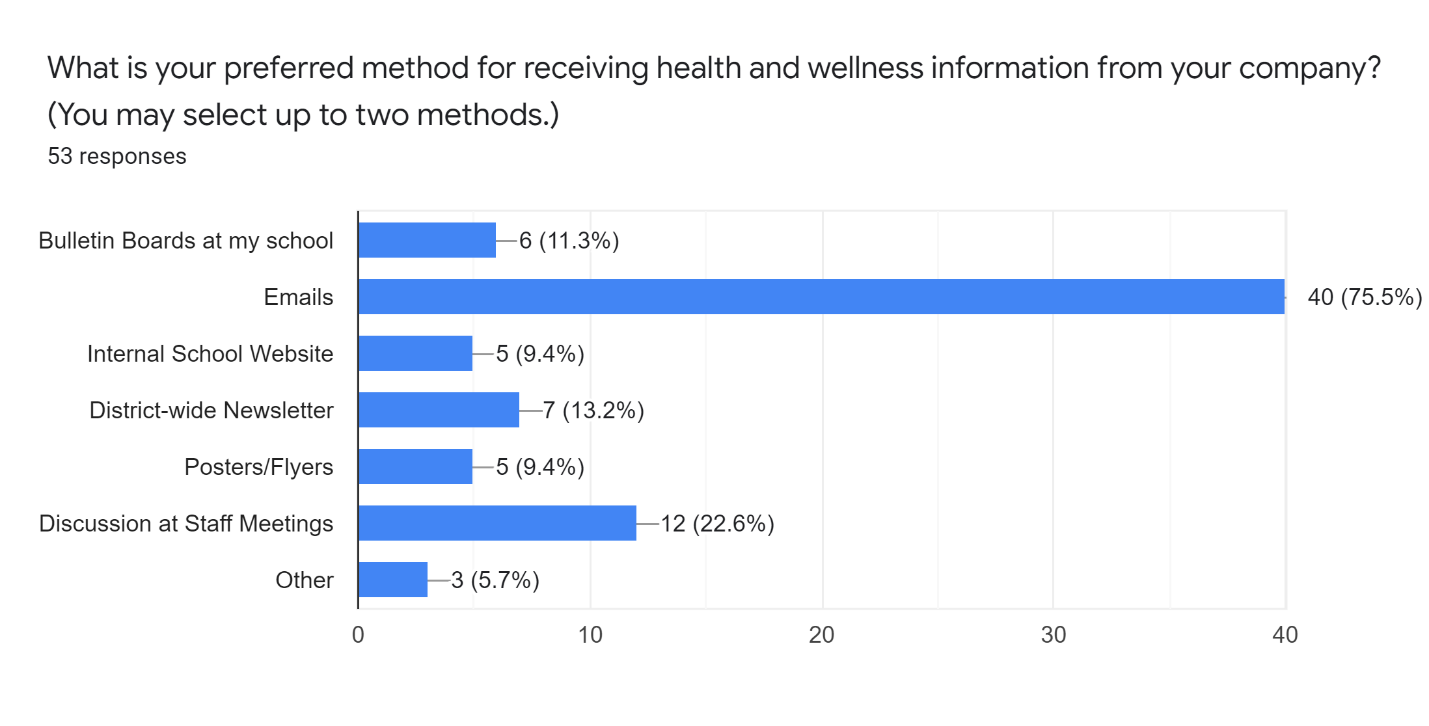

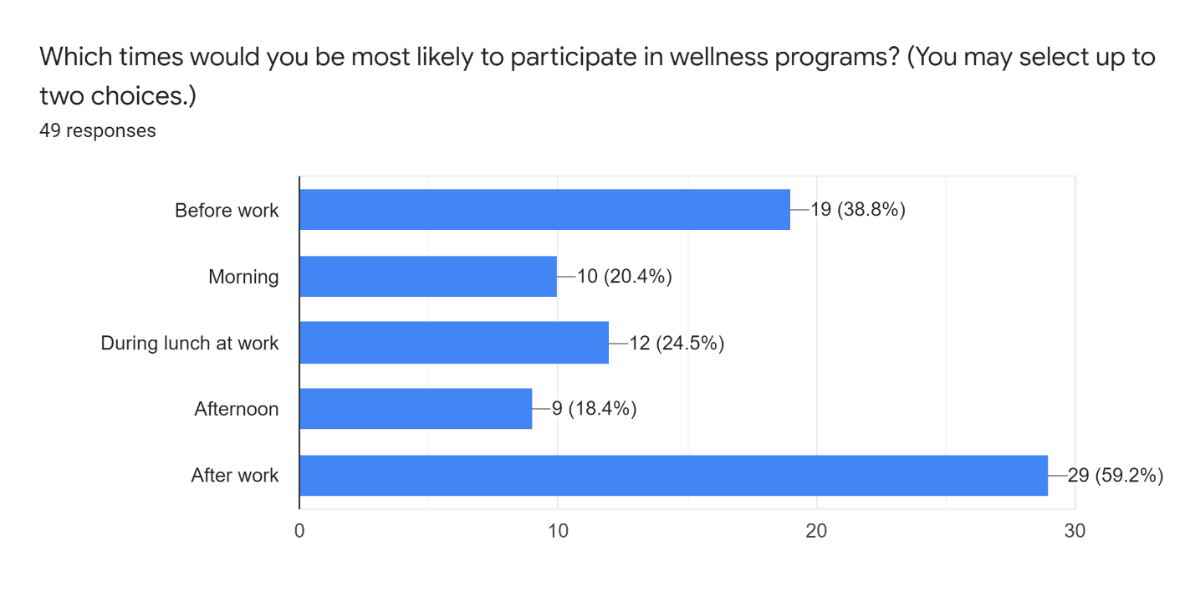

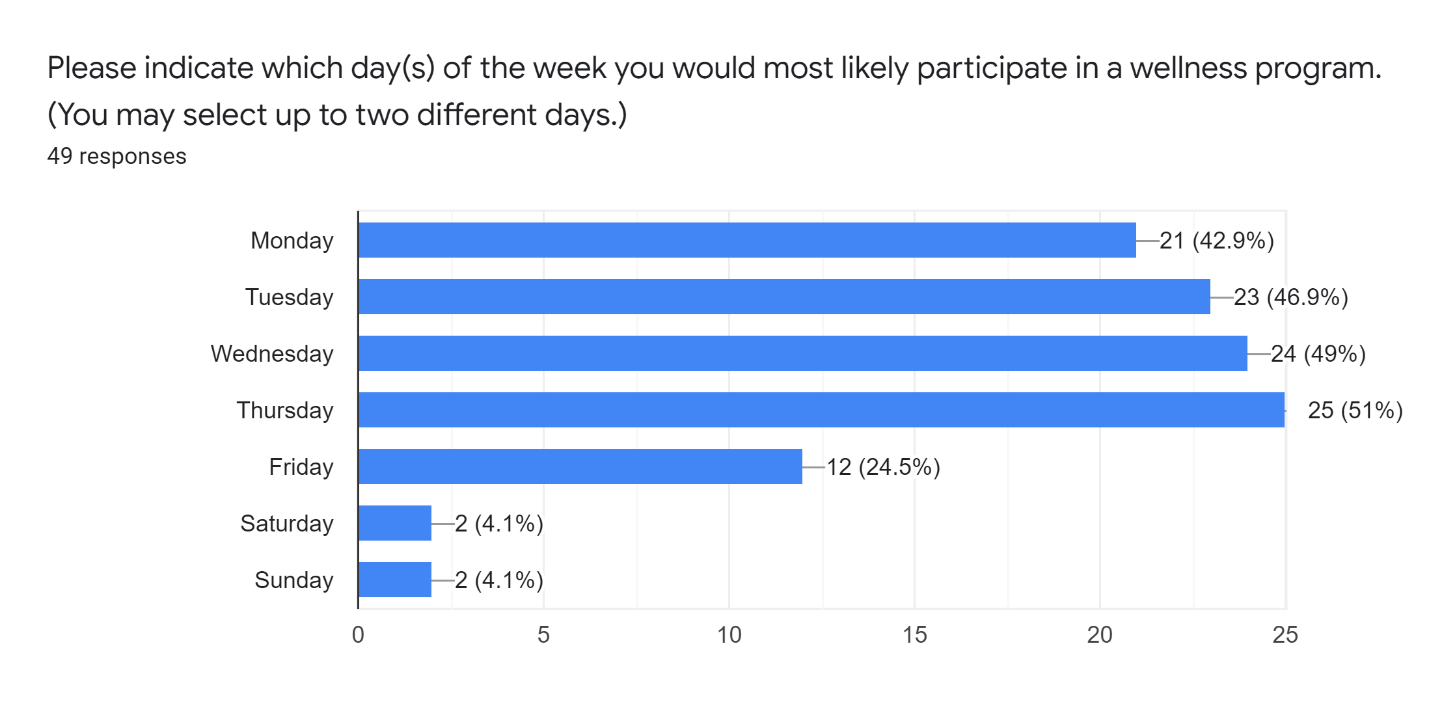

Qualitative data analysis allows for the categorization of themes and concepts that emerge from data provided related to how people experience a particular phenomenon (Creswell, 2014). Nominal, ordinal and ratio data were all derived from the survey results. Pie charts were used to further show the data collected from survey questions with a likert scale for opinion submission. The pie charts provided a visual representation of the data gathered to allow for me to see the results of each rating scale and multiple-choice question more clearly. According to Moustakas (1994), open-ended question responses can be analyzed in multiple ways. For the purpose of this research, I reviewed the responses and organized them into thematic connections. Additionally, I constructed a description of my own experiences from the free responses to distill information into a universal description of the opinions shared (Moustakas, 1994).

Following the data analysis process, conclusions from the trends were composed. Recommendations from the research were developed to support an increase in leadership support for employee wellness. Fiscal implications were reviewed to provide appropriate professional development for school and district leaders. Finally, based on the needs shared, recommendations were developed to provide opportunities for instructional staff to increase their own emotional well-being with supports and services from the school district. Options for financial support to implement the proposed recommendations was also reviewed to allow for an efficient and effective implementation process.

Institutional Review Board and Ethical Consideration

Because this research project involved human subjects, the Instructional Review Board’s approval was needed prior to the start of the project. On June 18, 2021, a final proposal for the research plan was submitted to the researcher’s Doctoral Capstone Committee for review and approval. Once the plan was approved, the Instructional Review Board application was completed. On August 6, 2021, the researcher submitted, by email, the Instructional Review Board request forms to the Instructional Review Board for approval. On August 13, 2021, the researcher received notification that the proposal had been accepted by the Instructional Review Board and that the application to conduct the research study was approved. The researcher was notified that the research must be submitted by August 12, 2022.

Ethical considerations are one of the most important factors of any research. Many principals of ethical considerations need to be reviewed as part of any study. The most important factors to consider, according to Bryman and Bell (2007) are:

- all participants of research should not be undergone to harm in any way;

- research participant’s dignity should be respected as the priority;

- full consent from the participants of research should be obtained before the study;

- ensuring adequate confidentiality levels of research; the anonymity of those who are participating in research should be ensured;

- any deception or exaggeration about the aims and objectives of the research must be avoided; and

- any communication types concerning research should be implemented with transparency and honesty.

Although the method of data collected for this survey included questionnaire-based surveys, the ethics of the research was maintained as a first priority. I ensured all participants were fully informed of the subject area prior to making their decision to participate. A detailed communication was sent to all invited participants and had to be read and agreed to prior to them having access to the survey. Additionally, they were fully informed of their option to withdraw from the process at any time. Finally, the participants were provided with my contact information, including my name, phone number and email address, as well as my committee chair’s contact information if they had additional questions or concerns prior to, or after, their participation in the research.

The survey did not include any of the population’s personal data, including but not limited to: names, birth dates, email addresses, grade levels taught, addresses, number of years in the district, district identification numbers, or building assignments within the district. Once a participant submitted their survey input, the results were housed on the district’s server, which is password protected and monitored for access. At no time was data entered able to be tracked to the participant or shared with anyone outside of the researcher.

Limitations