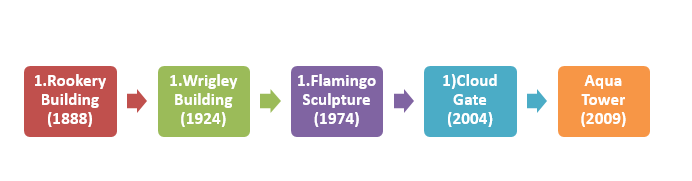

Rookery Building (1888)

The Rookery, a historic building in the heart of Chicago’s downtown Financial District, mixes the charm of a bygone age with cutting-edge building systems and technology. The Rookery, designed by legendary architectural partners Burnham and Root, was finished in 1888.

The Rookery is a transitional structure in the history of American architecture, using both masonry and metal construction technologies. It was built in the 1871 post-fire Chicago climate of technological innovation (Chicago Architecture Center, n.d.). The exterior walls are supported by masonry piers, while the interior structure is made of steel and iron. Root designed a revolutionary “floating foundation,” a system of iron rails and structural beams covered in cement that sustains the building’s weight, in order to establish such a large structure on Chicago’s soft clay soil. Many other characteristics of the building, such as passenger elevators and electricity, signaled the entrance of the modern era.

Wrigley Building (1924)

The Wrigley Building, situated in the heart of the Magnificent Mile and just minutes from the Michigan Avenue Bridge, has been a part of Chicago’s landscape since 1920. Architects Graham, Anderson, Probst & White designed a notable structure for such a prime spot (Chicago Architecture Center, 2012). The Wrigley Building was inspired by the Giralda tower of Seville Cathedral, which was mixed with French Renaissance elements.

The complex, which is made up of two towers of varying heights joined by pathways, is encased in glazed terra-cotta, which reflects light in the sunlight and during nighttime. The clock faces on the south clock tower are more than 19 feet in diameter and point in any and all directions. Another notable feature of the structure is that when entering the center doors, you are immediately transported to a peaceful park area with views of the Chicago River.

Flamingo Sculpture (1974)

In Federal Center Plaza in downtown Chicago, Alexander Calder’s 1974 “Flamingo” sculpture is a well-known magnet for visitors and locals alike. Alexander Calder, a prominent Modernist multi-media artist well known for his many amusing mobile inventions, designed the flamingo sculpture. The Flamingo, on the other hand, is the polar opposite of his mobile sculptures, which are distinguished by their dynamic mobility — he called the goliath sculpture a “stabile,” a freestanding sculpture built in the form of a mobil but sitting stiff and still (Emanuel, 2014). The sculpture’s vibrant hue and curved form contrast sharply with the neighboring angular steel and glass. The monumental, art-filled celebration was named “Alexander Calder Day” on October 25, 1974, and even included a circus parade.

Cloud Gate (2004)

Computer technology was used to cut, roll, and mill 168 plates of one-fourth-inch-thick stainless steel to achieve the perfect form and reflected finish of this sculpture by internationally acclaimed British artist Anish Kapoor, which was inspired by liquid mercury. The surface of the artwork reflects and distorts the city skyline, attracting visitors to capture photos with the most popular Chicago installation.

The internal steel foundation that was utilized to construct the artwork on-site has been detached to enable the sculpture’s stainless-steel exterior to expand and contract in reaction to temperature and air. The 12-foot-high centerpiece arch created a “gate” to the deep area on the sculpture’s bottom after it was fully built, inspiring Kapoor to officially call the piece Cloud Gate. Cloud Gate has become one of the most enormous global outdoor sculptural creations, weighing over 110 tons, and is Kapoor’s first public outdoor piece in the United States.

Aqua Tower (2009)

According to Studio Gang Architects, who built the structure under Jeanne Gang’s supervision, the Aqua Tower is a sculpture inspired by ridged limestone outcroppings seen in the Great Lakes region. Gang’s choice to make the Aqua Tower environmentally sustainable, with rainwater collection systems, heat resistant, and fritted glass, and energy-efficient lighting, also pays homage to the Midwest’s natural beauty (Glancey, 2009). The tower was conceived as a vertical environment made up of hills, valleys, and ponds, based on the qualities of terrestrial topography.

Aqua’s design incorporates architecture to preserve and reimagine the inherent human-environmental interactions that emerge when living closer to the ground. Its unusual shape is created by altering the floor slabs throughout the tower’s height, dependent on factors such as sight, daylight, and use (Glancey, 2009). The overall design is the product of adaptations to unique density, ecology, and use conditions.

Local Creative Residents

Kerry James Marshall

Kerry James Marshall’s structurally complex art, whose central protagonists are always “unequivocally, emphatically black,” confront the oppression of African-Americans (Kerry James Marshall, 2019). Marshall’s compositions are structured by his encyclopedic knowledge understanding of art history and black folk art; he exploits black culture and prejudices for his incisive subject area. His artworks are centered on identification; specifically, he made black aesthetic evident and included it into the great narrative of art. Marshall believes that art is where the wheels of historical and institutional power in Western art dwell.

Kerry James Marshall was influenced by the work of Bill Traylor, a self-taught, enslaved artist from Alabama when he was a student at Otis, and it motivated him to make additional artwork based on old-timey, grinning racial tropes (Kerry James Marshall, 2019). With such a unique style and composition, Marshall is among the most prominent Chicago residents, deserving to be displayed at the library.

Michelle Grabner

Michelle Grabner’s post-minimalist paintings and drawings reintroduce craft components to artistic production methods. Grabner frequently uses embroidery, wallpaper, or plaid patterns as prototypes or uses obscure geometry, such as Archimedes spirals, in which each point in a spiral is equivalent from the point before it and the one after it. Grabner’s innovative method of repetition reveals new dynamic relationships. Grabner explores the boundaries of compositional structures to find the critical point between stability and fragility by paying close attention to abstract patterns and all the metaphors they generate.

Almost all of her work is painted in two tones, highlighting the complexities of positive and negative space, as well as the texture of the canvas, and blending formalism with socio-political themes. Grabner’s outstanding works that are displayed in various museums all over the world undoubtedly deserve a place in the library exhibition.

Jim Nutt

In the 1960s and 1970s, Jim Nutt was a member of the Chicago-based Imagist and Hairy Who groups. In 1965, Nutt formed the Hairy Who with five other recent graduates of the School of the Art Institute, and the group began mounting unorthodox exhibits of vivid graphic work in the (Nutt, 2018). They altered Chicago’s art environment over the course of four years, injecting their new and unique voices into the city’s burgeoning national and international image.

In contrast to the prevalent New York abstraction, his graphic, passionately sexual, and psychological style was inspired by African and American Indian art, Surrealism, Expressionism, and the depiction of comics. In recent decades, Nutt has concentrated on flat, stylized women with distinctive huge face features. Numerous art institutions throughout the world have Nutt’s work in their collections. Therefore, such a remarkable painter must be included amongst other creative artists of Chicago in the library.

References

Chicago Architecture Center. (n.d.). Rookery Building. Web.

Chicago Architecture Center. (2012). Wrigley Building. Web.

Emanuel, R. (2014). The Chicago public art guide. Department of Cultural Affairs and Special Events City of Chicago. Web.

Glancey, J. (2009). Aqua Tower – the tower that Jeanne Gang built | Jonathan Glancey. The Guardian. Web.

Kerry James Marshall. (2019). Art21. Web.

Nutt, J. (2018). Jim Nutt | The Art Institute of Chicago. The Art Institute of Chicago. Web.