Introduction

This report is an assessment of the extent to which external macroeconomic factors have contributed to the slowdown of UK’s economic growth as compared to domestic factors. The measures taken by the British government and the Bank of England in the last two years to enhance the rebound of the economy will be compared with those taken by other governments and central banks. Additionally, the measures taken by the British government and the Bank of England will be analyzed in order to determine their effectiveness.

Background

The challenges facing UK’s economy began in 2008, following the 2008/2009 global financial crisis. Due to the financial crisis and a huge public debt, UK entered a recession in 2009. The government and the Bank of England responded to the economic decline through fiscal and monetary policies respectively. Thus, in 2010, UK left the recession with a GDP growth of 0.4% in the first quarter of the year (Sawyer 2011, pp. 13-29).

However, the steady recovery was only maintained up to the third quarter of 2011. From the fourth quarter of 2011, UK’s economy began to contract again, thereby raising fears of a double-dip recession. A double-dip recession is a situation whereby “a recession is followed by a short recovery, followed by another recession” (Martin & Miler 2010, pp. 443-459).

In the first quarter of 2012, UK’s GDP further contracted by 0.2%. The construction industry which is the most affected experienced a reduction in output by 3%. Some economists predict that the economy might enter a full recession in the near future. However, the main causes of the economic slowdown are not clear.

Effects of the Domestic Factors

The domestic factors associated with the economic crisis in UK include the following. First, UK’s huge public debt is partly responsible for the economic crisis. Both public and private debts grew to unsustainable levels, prior to the 2008/2009 financial crisis (HM Treasury 2011, pp. 5-104). For instance, the nonfinancial firm’s debt reached 110% of the GDP in 2008.

The private and public sector borrowed from abroad, thereby increasing UK’s current account deficit to over 3% of GDP. In 2007, the government based its spending plan on unsustainable revenues. As a result, the tax receipts were less than the planned expenditure. This worsened the debt crisis, and public spending increased to 47% of GDP in the 2008/2009 financial year (HM Treasury 2011, pp. 5-104).

Increased public borrowing led to higher prices of public services, whereas private investments reduced. Second, UK had an unbalanced growth. Economic growth was only strong in the South East, while the rest of the country depended on jobs supported by public spending. In order to support these jobs, the government had to continue borrowing, thereby worsening the dept crisis and crowding out private investments. Third, the saving rate reduced from 10% in 1994 to less than 1% in 2007 (Morald & Plummer 2010, pp. 208-219).

As the saving rate reduced, households relied on borrowing to finance their expenditures. However, banks have since reduced credit availability in order to recover from the 2008/2009 crisis.

The resulting reduction in aggregate demand has led to slow economic activity. Fourth, weak consumer, as well as, investor confidence has constrained economic growth through low aggregate demand. Finally, the austerity measures such as job cuts in the public sector have had a contractionary effect on UK’s economy (International Monetary Fund 2010, pp. 1-32).

Effects of International Factors

The international macroeconomic factors that have contributed to UK’s economic crisis include the following. To begin with, the Euro-zone financial crisis has adversely affected UK. In particular, the Euro-zone crisis has had a negative demand shock in UK. The decline in aggregate demand in Europe (UK’s main export market) has led to a reduction in UK’s exports earning.

This decline has translated into high unemployment rate and low income per capita in UK. Additionally, UK’s financial system is integrated with those of other European countries. Thus, debt defaults in the Euro-zone have had a negative spillover effect in UK. Second, UK’s currency is still stronger than the major international currencies.

Hence, UK’s exports have declined as its products become uncompetitive in foreign markets. Additionally, competition from emerging economies such as India and China has reduced demand for UK’s exports. Finally, high interest rate and stability in foreign markets has led to capital flight from UK. Consequently, the level of investment in UK has declined since the beginning of the global financial crisis.

It is apparent that both domestic and international macroeconomic factors have significantly, contributed to the slowdown in UK’s economy. The economic crisis was initiated by the domestic factors, especially, the public and private sector debt (Eichengreen, Feldman, Leibman 2011, 25-164).

The international factors such as the Euro-zone crisis worsened the situation. For instance, the government’s attempt to reduce its debts in 2007 was thwarted by the global financial crisis which prevented the government from maximizing its tax revenue.

Measures Taken by the Government and the Bank of England

The UK’s economic policy aims at “achieving a strong, sustainable and balanced growth that is more evenly shared across the country and between industries” (HM Treasury 2011, pp. 5-104). Hence the objective of the economic policy is to achieve economic growth, stability and fairness.

The objective of the fiscal policy is to control government spending in order to reduce the public debt in the medium term. The objective of monetary policy, on the other hand, is to achieve price stability which in turn will spur a wider economic stability. The fiscal policy being pursued by the government can be explained as follows.

In order to promote rapid economic growth, the government decided to reform the tax system. The reform is expected to make tax compliance simpler and cheaper. In 2011, the corporate tax was reduced to 26% down from 27% in 2010 (HM Treasury 2011, pp. 5-104).

The government intends to reduce the corporate tax to 23% by 2014. Additionally, the government is implementing a progressive tax system that aims at redistributing income from the rich to the poor. In order to enhance investment and exports, the government allocated 300 pounds for expanding the rail network and road maintenance.

The government also intends to “establish 21 new enterprise zones” (HM Treasury 2011, pp. 5-104). The government has since increased expenditure on education and health. For instance, in 2010, the government adopted a plan to build 24 new collages and to improve access to health care through NHS.

The government intends to reduce borrowing from the public from 11% of GDP in 2009 to 1.1% of GDP by 2016 (HM Treasury 2011, pp. 5-104). In order to achieve this objective, the government has embarked on fiscal consolidation by reducing welfare costs, as well as, wasteful spending (HM Treasury 2010, pp. 6-106).

Finally, the government intends to promote fairness by reducing inheritance tax, reforming the pension system, reducing tax avoidance and reducing fuel duty. The Bank of England has increased money supply by reducing its interest rate to 0.5%. It has also improved regulation in the financial sector in order to promote growth. The effect of the fiscal and monetary policies implemented by the government and the Bank of England respectively can be illustrated by the IS-LM and the IS-PC-MR model.

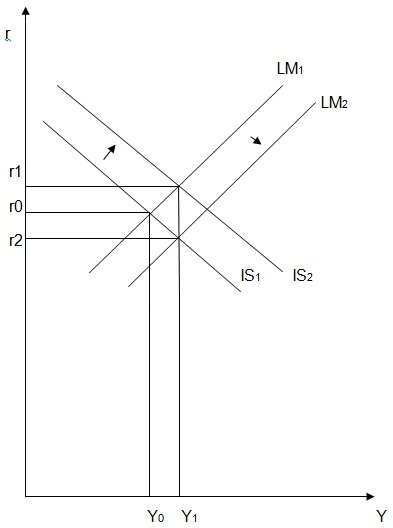

The IS-LM Model

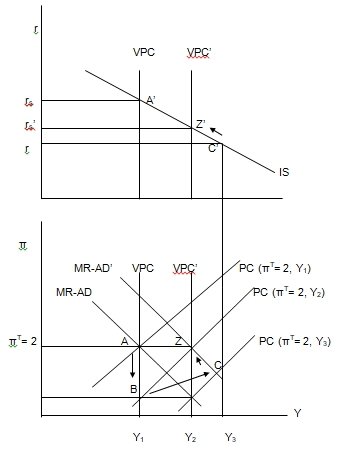

Figure 2 below shows the IS-PC-MR model. The economic stimulus package and tax cuts implemented by the government have the impact of a positive supply shock in the economy. Consequently, output will increase from Y1 to Y2. Both the vertical and the short-run Philips curves shift to the right.

Thus, the inflation rate will fall below the target rate of 2% as equilibrium moves from point A to B. In order to achieve the targeted inflation rate, the Bank of England predicts the PC constraint and chooses the optimal level of output (point C in graph 2). In order to achieve the optimal output level, interest rates have to be reduced (Blanchard 2008, p. 235). Thus, the Bank of England reduced its interest rate to 0.5%. The economy will then be guided to a higher equilibrium (point Z). In general, a positive supply shock causes a reduction in inflation and an increase in output in the short run. This perhaps explains the reduction in UK’s inflation between 2010 and 2011, as well as, the increase in output over the same period.

The IS-PC-MR Model

Figure 2 below shows the IS-PC-MR model. The economic stimulus package and tax cuts implemented by the government have the impact of a positive supply shock in the economy. Consequently, output will increase from Y1 to Y2. Both the vertical and the short-run Philips curves shift to the right.

Thus, the inflation rate will fall below the target rate of 2% as equilibrium moves from point A to B. In order to achieve the targeted inflation rate, the Bank of England predicts the PC constraint and chooses the optimal level of output (point C in graph 2). In order to achieve the optimal output level, interest rates have to be reduced (Blanchard 2008, p. 235). Thus, the Bank of England reduced its interest rate to 0.5%.

The economy will then be guided to a higher equilibrium (point Z). In general, a positive supply shock causes a reduction in inflation and an increase in output in the short run. This perhaps explains the reduction in UK’s inflation between 2010 and 2011, as well as, the increase in output over the same period.

Measures Taken by other Governments and Central Banks

Nearly all countries in Europe are facing a financial crisis. Consequently, most of them are implementing stabilization policies. Denmark adopted an exchange rate-based stabilization by devaluing its currency through wage restraint, as well as, income policies (Perotti 2011, pp. 2-60).

Denmark’s inflation and interest rates initially reduced, causing domestic demand to increase. However, as the competitiveness of Denmark’s exports worsened, the current account deficit increased and growth reduced. In Ireland, the local currency was depreciated before the implementation of fiscal consolidation. Additionally, Ireland’s exchange rate was fixed “within the European Exchange Rate Mechanism (ERM)” (Perotti 2011, pp. 2-60).

In Sweden and Finland, fiscal consolidation was implemented under a floating exchange rate and inflation targeting. Hence, the currencies of these countries depreciated and their exports increased. Additionally, the central banks of Sweden and Finland significantly reduced their interest rates.

In the US, the Fed lowered its interest rate in order to increase liquidity. The Fed also embarked on credit easing by buying mortgage-backed securities from the public (Wallison 2012, pp. 71-77). The government of US implemented fiscal stimulus packages as a response to its debt crisis.

In conclusion, most countries in Europe have responded to the financial crisis through fiscal consolidation and economic stimulus packages. However, UK’s fiscal consolidation differs from those of its peers in terms of timing, the extent of fiscal retrenchment and the range of austerity measures taken by the government. In US the fiscal policy is expansionary and is likely to increase the budget deficit by 1% of GDP in 2012 (Wallison 2012, pp. 71-77).

Effectiveness of UK’s Fiscal and Monetary Policies

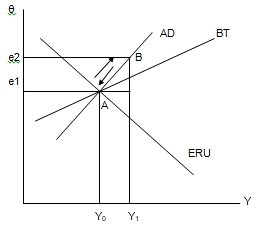

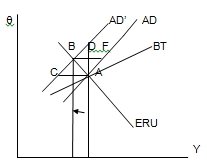

As stated earlier, the objective of UK’s economic policy is to enhance, growth, stability and fairness. The extent to which these objectives have been achieved can be analyzed using the AD-BT-ERU model.

Monetary Policy

Consider the AD-BT-ERU model illustrated by figure 3. The Bank of England has loosened the monetary policy by lowering the interest rate. Thus, net exports, as well as, output will increase from Y0 to Y1 and the short-run equilibrium will be at point B. The exchange rate will also depreciate from e1 to e2.

The depreciation causes the prices of imports to increase while the prices of exports remain constant. Thus, the country’s terms of trade deteriorates. The increase in the price of imports directly affects the CPI, thereby reducing the real wage rate (Mankiw 2009, p. 341). Wage setters will respond to the increase in employment and the reduction in real wage in the medium term.

The increase in output in the short run will be accompanied by inflationary pressures. Consequently, the real money wage will be higher as compared to the expected prices. Since the nominal exchange rate will remain constant after its initial depreciation, the rise in CPI will be less than the rise in money wages. As a result, the economy will operate above the ERU curve and the domestic inflation rate will be higher than the world inflation.

Thus, the competitiveness of UK’s exports will reduce and the economy will return to point A. In the last 4 years, UK’s currency depreciated by 25%, thereby increasing exports, reducing the trade deficit and promoting economic growth (Kamath 2011, pp. 294-303). Going by the AD-BT-ERU analysis, these gains are likely to be lost in the medium term and the economy will return to the low output level (point A in figure 3). This suggests ineffectiveness of the monetary policy.

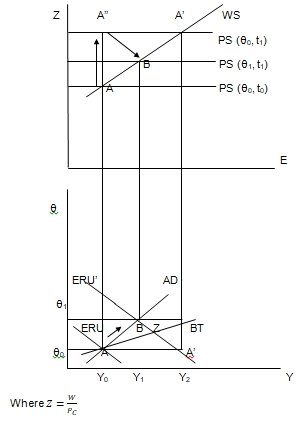

Tax Cuts

Consider the AD-BT-ERU model illustrated by figure 4 below. The tax cut causes the ERU curve to shift to the right. A reduction in tax rate from t0 to t1 shifts the PS (θ, t0) curve to PS (θ, t1). Thus, the equilibrium will move from point A to A’. Additionally, the ERU curve will shift to ERU’.

The AD curve will not shift since the tax cut effect is expected to be offset by the reduction in government spending. Thus, point B and Z will be the new medium and long run equilibrium respectively.

The real wage will exceed the wage-setting real wage and the economy will operate below the ERU’ curve. Hence, both nominal and real wages will reduce and the competitiveness of exports will increase. The economy will move from point A’ to B. Since point B has a higher output than point A, the tax cut policy will be effective.

Austerity Measures

Consider the AD-BT-ERU model illustrated by figure 5 below. The austerity measures taken by the government can be conceptualized as negative demand shocks since they reduce aggregate demand and investments (Baker 2010, pp. 3-14). The negative demand shock will lead to a depreciation of the exchange rate in the short run, whereas output will remain fixed at point D.

Output is unchanged since the reduction in output due to a fall in aggregate demand is offset by the depreciation caused by reduction in interest rate. The depreciation reduces the real wages and the domestic inflation will exceed that of the world (OECD 2010, pp. 2-47). Consequently, the competitiveness of UK’s exports will reduce.

Additionally, output will fall from Y0 to Y1 as the economy moves to a new equilibrium at point B. The reduction in output at the new equilibrium shows that the austerity measures are ineffective. This is because they lead to a contraction as opposed to the government’s objective of achieving a higher economic growth.

Conclusion

The measures taken by the government and the Bank of England in response to UK’s economic crisis, to a large extent, are similar to those taken by other European countries. The government of UK has focused on fiscal consolidation, while the Bank of England has loosened the monetary policy.

The impact of these measures are reflected in the rise in output between 2010 and the third quarter of 2011, as well as, the decline in output from the last quarter of 2011 to the first quarter of 2012. Empirical studies reveal that fiscal consolidation reduces economic growth (Perotti 2011, pp. 2-60). This is inline with our findings that austerity measures are likely to reduce output. Our findings also show that UK’s monetary policy will reduce output by reducing the competitiveness of its exports.

Thus, in the short run, the measures taken by the government seems to be ineffective. While fiscal consolidation is necessary to reduce the pubic debt, the government and the Bank of England should also take some expansionary measures to enhance economic growth. In the long run, the fiscal consolidation is likely to spur growth if it succeeds in reducing the debt burden.

Figure 1: IS-LM Model

Figure 2: IS-PC-MR Model

Figure 3: Monetary Policy

Figure 4: Tax Cut

Figure 5: Austerity Measures

References

Baker, D 2010, The Myth of Fiscal Austerity, Center for Economic and Policy Research, Washington D.C.

Blanchard, O 2008, Macroeconomics, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Eichengreen, B, Feldman, R & Liebman, J 2011, Public Debt: Nuts, Bolts and Worries, Center for Economic Policy Research, London.

HM Treasury 2011, Budget 2011, The Stationery Office, London.

HM Treasury 2010, Spending Review 2010, The Stationery Office, London.

International Monetary Fund 2010, Will it Hurt? Macroeconomic Effects of Fiscal Consolidation, IMF, Washington D.C.

Kamath, K 2011, Understanding Recent Developments in UK External Trade, Bank’s Structural Economic Analysis Division, London.

Mankiw, R 2009, Macroeconomics, McGraw-Hill, New York.

Martin, C & Miler, C 2010, ‘Financial Market Liquidity and the Financial Crisis: An Assessment Using UK Data’, International Finance, vol. 13 no. 3, pp. 443-459.

Morald, M & Plummer, M 2010, ‘Surviving the Economic Crisis’, Local Economy, vol. 25 no. 3, pp. 208-219.

OECD 2010, Fiscal Consolidation: Requirement, Timing, Instruments and Institutional Arrangements, OECD, Paris.

Perotti, R 2011, The Austerity Myth: Gain without Pain?, Center for Economic Policy Research, London.

Sawyer, M 2011, ‘UK Fiscal Policy after the Global Financial Crisis’, Contributions to Political Economy, vol. 30 no. 1, pp. 13-29.

Wallison, P 2012, ‘How and Why a US Sovereign Debt Crisis could Occur’, Economics Journal Watch, vol. 9 no. 1, pp. 71-77.