Introduction

Research Area

St. Lucie County School District refers to the school district that manages schools in St. Lucie County, Florida, USA, and is branded as St. Lucie County Public Schools. The students from St. Lucie schools learn English as their second language.

Research Aim

This study explores the teaching methods used in St. Lucie schools to teach the English language to identify conflicting policy issues regarding the teaching of English to Language Learners in other states.

Objectives

The main objective of this study is to investigate the policies guiding the teaching of the English Language in St. Lucie schools. Other objectives include comparing the policies formulated by the state and the federal on English language learners towards language education.

Justification

English is the second language for most of the students studying in St. Lucie Schools. According to statistics, 1 out of 5 adults cannot read well enough to complete a job application or read newspapers. This study will help in analyzing the St. Lucie policies on English Language Learners. The study will help one to understand the state and federal policies as well as the local school district policies’ viability and whether these policies conflict with each other to guide an informed action on the matter. Though there have been numerous studies in the St. Lucie education program very few researchers have engaged in specifically addressing the policy issues in English teaching between the county schools and other states.

Literature Review

US Department of Education

Policy on the US English tests is not standardized and neither does it cater to the needs of the English language Learners. This is a pressing issue regarding the performance on the standardized tests being used thus making language a liability for ELLs’ when the results are the sole criteria for major decisions. Tests have become very important since they are being used in the majority of the states as the main criteria for high school graduation, grade promotion, and placement into tracked programs (Wodak and Corson, 1997). The standardized tests used in most states currently, were developed for the assessment of native English speakers and not ELLs. In this way, these tests are language proficiency exams, and therefore they don’t necessarily measure the knowledge content of the student (Menken, 2008). Consequently ELLs across the US are performing poorly on the standardized tests being used in compliance with the No Child Left Behind, and their scores are being used to make major decisions. A study on the Ells’s performance shows that they perform 20-40 percentage points below other students on statewide assessments. The irony in this is that ELLs are disproportionately being left behind (Riceto, 1998).

State board education

The State Board of Education (SBE) was first established in 1852 through the amendment to the California Constitution in 1884 (Saracho and Spodeck, 2004). The Constitution and statutes set forth the SBE’s duties. Among the duties of the SBE is to appoint the senior officials of the committee and discuss the best books to be adopted in the learning and teaching of the English language for grades 1 to 8.

Implementation Procedures

State Board Education

SBE is the governing and policy-making body following the provisions by CDE which also allocates various duties to SBE which include setting the governing rules, the appointment of its officials, and those of the state’s public schools (Wodak and Corson, 1997).

Local School District

History of Language policies in the US

According to Wodak and Corson (1997), language in the US is derived from the following sources: official enactments of governing bodies or authorities, such as legislation, executive directives, judicial orders or decrees, or policy statements; and non-official institutional or individual practices or customs. The evolution of language policies may be as a result of the government not taking any action, for example, the government may fail to provide support for the teaching or learning of a particular language or language variety, or by designating and promoting an official language and ignoring other languages, or through the failure of provision of adequate resources to ensure all groups have equal opportunities to acquire the official language in educational settings (Wodak and Corson, 1997). The evolution of policies may also arise from grassroots movements and become formalized through laws, practices, or some combination of both (Schmidt, 2000). The main focus of the earliest work in language policy in the US was on the status of English vs. Non- English languages from the colonial period through the mid-nineteenth century.

According to Shohamy (2006), the history of languages in North America began with the arrival of the first Europeans in the 16th century; Simpson (2009) describe the British legacy of tolerance towards the non- English languages coupled with an aversion to strict standardization of English common in the United States until the mid-nineteenth century. Tolerance was only applicable to European languages speakers; Native American languages and cultures were stigmatized, and government policy, beginning in 1802, was to separate Indians from their cultures (Wodak and Corson 1997). Colonies, such as Virginia and South Carolina passed compulsory ignorance laws and were later followed by other states making it a crime to teach slaves, and sometimes free – blacks, to read or write (Simpson, 2009). At the onset of the 1850s, the development of a common public school system, coupled with a nativist movement beginning in the 1880s, resulted in the imposition of the English language of instruction in public and most parochial schools by the 1920s (Maykut and Morehouse,1994).

Before 1889, only three states had laws that prescribed English as the language of instruction in private schools. However, by 1923, thirty-four states had ratified the use of English in schools (Riceto and Burnbay, 1998). The state of California (1921) and Hawaii (1920) enacted legislative laws that were geared towards the abolishment of offering foreign languages in lower levels of learning. The case Meyer v. Nebraska (1923), a 1919 statute that forbade teaching in any language other than English was found by the US Supreme Court and was declared unconstitutional. In 1927, the Court upheld a ruling by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals (1926) which had discovered laws prohibiting the teaching of non- English languages in twenty- two states to be unconstitutional (Menken, 2008).

The era 1930 to 1965 had no events concerning federal intervention in language policy issues, except for the continued intrusion of U.S. influence in language- in- education policy in Puerto Rico (Menken, 2008), and restrictive policies towards the use of Japanese and German in public domains from the 1930s through World War II. The federal and state governments failed to address the educational needs of language minority students and other historically marginalized groups and this translated to policymaking through inaction. At the onset of the 1960s, a more active role was taken in accommodating non- English languages in education (Saracho and Spodeck, 2004). The role of the federal increased in two ways: one it added the expenditures under Titles I, IV, and VII of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act presently the Improve America’s Schools Act, or IASA and increased role in the enforcement of civil rights laws in education (Saracho and Spodeck, 2004).

A policy on bilingual education was formulated as the first major federal involvement in the area of status planning. This policy was enacted under the Bilingual Education Act (BEA) of 1968 which authorized the use of non- English languages in the education of low-income language minority students who had been segregated in inferior schools or had been placed in English-only classes (Riceto and Burnbay, 1998). There were other programs supported by the federal government that dealt with language and education and they include the Native American Language Act of 1990 that endorsed the preservation of indigenous languages. The Act requires government agencies to ensure that their activities promote this goal. The other program supported by the federal government was the National Literacy Act of 1991, which authorized literacy programs and established the National Institute for Literacy. A provision of statutory bases has been made by the Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act and the Equal Education Opportunities Act of 1974 provided the statutory bases.

On the other hand, the equal protection clause of the fourteenth Amendment of the U.S. Constitution provided the constitutional reason for expanding opportunities for language minority students in several important court cases. For example, the Lau v. Nichols (1974) decision, in which the US Supreme Court, relying on sections 601 and 602 of Title VI of the 1964 Civil Rights Act, found that the San Francisco School District had failed to provide a meaningful educational opportunity to Chinese ancestry students due to their lack of basic English skills (Saracho and Spodeck, 2004). There were no specific remedies given by the court; the office for Civil Rights of the Department of Education however wrote guidelines (the LAU Remedies) which instructed school districts on how to identify and evaluate limited and non- English- speaking children, instructional “treatments” to utilize, including bilingual education, exit criteria, and professional teaching standards. There has been political opposition to one remedy known as maintenance bilingual education programs, thus leading to increased federal support for transitional bilingual education programs, whereby students are excited to English- only classrooms after three years in bilingual classrooms, also offering alternative instructional models, like English as a second language (ESL) programs.

Before 1978, children of Native American backgrounds were not qualified for admission to federally funded bilingual programs because English was reported as their dominant language. According to linguists and educators, however, they concluded that the variety of English used that is Indian English creates difficulties in the English- only classroom. In the year 1986- 87, only about 11% of Title VII education grants were designated for Indian children amounting to near $ 10 million. The task force that was formed to look into the issues of English language learning for Indian Nations reported to the secretary of Education in 1992 with the following recommendations for the year 2000:

- All schools that serve Native students should allow the students to maintain and develop their tribal languages.

- All Native children should have early childhood education providing the needed “language, social, physical, spiritual, and cultural foundations” for school and later success.

- A curriculum that is “culturally and linguistically appropriate” and implements the provisions of the Native American Language Act of 1990 in public schools should be implemented (Wodak and Corson, 1997).

Several factors have however prevented successful of the Task Force recommendations. Attempts were made to give the native languages educational status but several tribes adopted official language policies in the 1980s, including the Navajo, Red LAKE Chippewa, Northern Ute, Arapahoe, Pasqua Yaqui, and Tohono O’ odlam (Papago) (Wodak and Corson, 1997).

A policy for English as a second language has been enacted under a variety of federal and state programs, including Chapters I and VII of the Elementary and Secondary Education Act (ESEA), which is currently known as the Improve America’s Schools Act of 1991, the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA) OF 1986, The Adult Education Act (Perkins Vocational and Applied Technology Education Act – Perkins Act) (Saracho and Spodeck, 2004).

Research Method

Introduction

This chapter aims at discussing the research methods being used and applied in this study. The chapter first seeks to explore the research design to be used. Various data collection methods are going to be discussed and analyzed in this chapter. Also, the data collection methods used will be discussed whereby there will be an explanation as to why each particular data collection method was used.

Research Question

To carry out the research and tackle the main issue of the study, it is necessary to indicate the research before deciding on the research methods to use for one to evaluate the ability of the chosen research method to adequately collect data that would respond to the research question effectively. The following primary research question will be explored in this study;

How effective is the St. Lucie district language policy?

To aid in a focused and specific data collection, the secondary questions regarding the schools’ policy adopted for the study are;

- How the school defines ELL students?

- How does the school identify ELL students?

- How does the school place ELL students into classrooms?

- How does the school monitor the language progress of ELL students?

- How successful the ELL students have been in that school based on different types of standardized assessments?

- How are the transitions of ELL students done into the mainstream classroom based upon those assessments?

Research Design

In research, this refers to the overall approach adopted by the study for collecting the desired data for results formulation. The current study adopts a phenomenological approach. According to Maykut and Morehouse (1994), two broad strategies are applied in conducting research. They include; the phenomenological and the positivist approach. The following characteristics justify this study as a phenomenological approach;

- The respondents in the study provide the information to be used for results analysis through the prepared questionnaires. In the positivist approach, the researcher prepares information frameworks that attempt to evaluate the respondents (Wodak and Corson, 1997).

- The objectives were set to understand opinions on the item under study through both the primary data collection and reliance on existing literature as opposed to the positivist approach which aims at collecting empirical data.

Data collection methods

This study aims at collecting factual information that can act as a guide on how language policies in St. Lucie district schools affect language learning. To achieve a focused and reliable approach in data collection, the researcher established and relied on one instrument, that is, interviews. The researcher conducted live interviews and in the case where it was impossible to do live interviews, it was done through the phone. Interviews were found appropriate in this study for the following reasons;

- Interviews ensure that there are responses that a researcher obtains in an interview that would otherwise be unavailable in questionnaires. This includes facial expressions, signs, and gestures that are normally exhibited in interviews and they help in gathering rich information on the question under study.

- Interviews guarantee that the actual targeted person is reached.

One disadvantage with this method, however, is that is likely to get too much unnecessary information.

In total, 10 interviews were carried out. The interviewees included;

- Two district education directors – 1 male, 1 female

- South Port Middle school teachers – 1 male, 2 female

- Parents – 1 male, 2 female

- Educational consultants – 1 male, 1 female

Data Analysis and Results

Study Findings

Personal Details of the Respondents

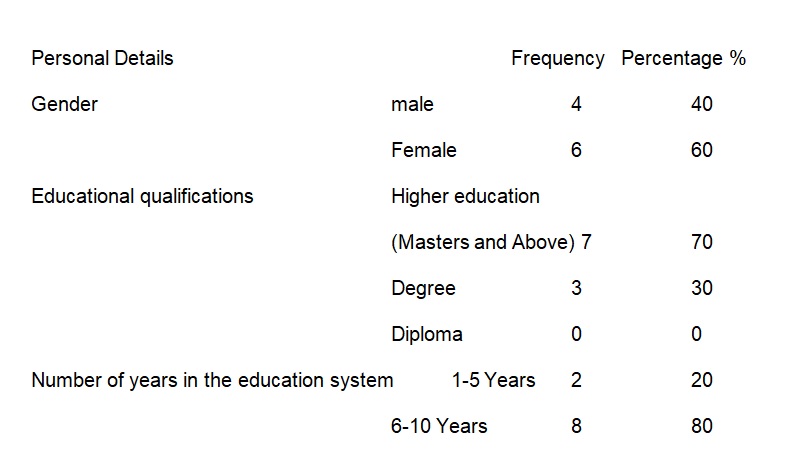

The researcher collected the personal details of the sample target and these included basic data like; gender, educational background, and the number of years they have worked as ELL teachers or policymakers in the ELL program. The data that was collected is tabulated below;

The data from table 1 shows that most of the respondents were female (60%) while only 40% were male. Additionally, the majority of the respondents had higher educational qualifications with those with masters and above accounting for 70% and 30% with a university degree and none had diploma qualifications. Furthermore, 80% of the respondents had a working experience of 6 years and above in the educational sector and only 20% had a working experience of fewer than 5 years.

Organizational Data Findings and interpretation

Definition of ELL

An ELL student was defined by 35% of the respondents as an individual who was originally not born in America and hence the indigenous language is a language different from English. Additionally, this individual comes from an environment where another language other than English is spoken. 65% of the respondents defined ELL as the students in English language schools whose first language is a language that is not English or is a variety of English which is considerably different from that used for instruction in schools. Hence these students may require additional educational support to assist them in attaining the required proficiency in English.

How ELL students are identified

All the respondents (10) unanimously agreed that the ELL students are identified through the use of surveys and testing. Interviews are conducted with the students together with their parents on various issues ranging from; the students’ hobbies, experience in school in particular subject areas, previous access to school, and other relevant information. The students are then classified as Limited English Proficient (LEP). This then helps to identify them as English Language Learners (ELL).

Placement of ELL students into Classrooms

ELL students according to 75% of the respondents are placed into the classrooms after the survey and testing are completed. The score a student gets in the oral proficiency test is the one that determines the students’ placement. The students are then given an educational plan and also assigned a committee that consists of the individual school’s English for Speakers of Other Language (ESOL) homeroom teacher, teacher, and counselor. 25% of the respondents said that the ELL students are placed in age-appropriate groups. They however believe that ELL students are mostly placed in multilevel or multi-age classrooms that do not meet the needs of their academic content.

Monitoring of Language progress of ELL Students

The ELL students as per the responses of 90% of the respondents are tested and monitored regularly against grade-level criteria. This is done using a state-wide English proficiency assessment to determine the level of their progress and readiness to exit the program and subsequently be reclassified into the regular classroom programs. The other10% reiterated that in addition to these annual assessments the ELL students in 3-8th grade and once in high school have to participate in regular state assessment in academic content together with other students.

The transition of ELL students into the Mainstream Classroom

After successful assessment, all the respondents agreed that the students are reclassified as English proficient using the same assessment standards, instruments, and procedures that were used before, though they are adjusted for the current specific grade level and age. A two-year monitoring period is then set to monitor the students’ academic progress. 20% of them however were against the reclassification of the students who failed in the second monitoring back to ELL. They attributed this ‘demotion’ to the increased number of school dropouts.

The success of ELL in St. Lucie County School

76% of the respondents concurred that most ELL students continue to fall behind in achievement compared to their classmates who are native speakers of the English language. They accredited this to the use of standardized tests which are inappropriate due to the ever-increasing student population who do not speak English. However, they believe that the programs are better than none at all for the ELL students. Nonetheless, 24% said that ELL students who went through the program attained higher grades than the native English speakers.

Conclusion

South Port middle school has a significant number of ELL students. Based on the respondent’s data, it is evident that the school clearly defines an ELL student. Through the use of surveys and testing, all respondents were also unanimous that the school identifies ELL students. ELL students, once identified are placed into specialized classes in which they get standardized national tests to assess their language proficiency. According to the respondents, identification and placement into the right classes are achieved effectively. Although many ELL students are classified as English proficient after passing the tests, most respondents felt that such students continued to perform dismally when compared to their peers in class. As such, the school can undertake to improve its ELL programs using the recommendations below;

Recommendations

St. Lucie County School needs to provide the teachers with an intensive program that is designed to accelerate the students’ ability to acquire English proficiency in academic and everyday use in addition to the acquisition of appropriate skills and knowledge of numeracy and literacy.

Secondly, the teacher’s education programs need to be enhanced both at the in and pre-service levels. This can be done by mandating that the teachers be certified in the areas that they teach. At the same time high quality especially minority teachers should be recruited as they would best understand the needs of the student with low English proficiency.

More importantly, the school ought to channel the resources for instruction to focus more on learners in High school who are learning English since they are at a higher risk of falling out of school due to continued failure and discouragement from low-level grades in their assessment.

A standardized testing policy should not be adopted for language learners and native English speakers. This can be done by use of different testing methods in which case the language learners and the native English speakers are assigned different tests according to the levels of their knowledge in English.

Finally, the school and policymakers should further develop the instructional approaches of the English language to improve the achievements of ELL students.

References

Maykut, P., & Morehouse R., (1994). Beginning qualitative research: a philosophical and practical guide, New York: Routledge Farmer.

Menken, K., (2008). English learners left behind: standardized testing as language policy, New York, Multilingual Matters.

Riceto, T., & Burnbay, B., (1998). Language and politics in the United States and Canada: Myths and Realities, New York: L. Erlbaum.

Saracho, O & Spodeck, B. (Eds), (2004). Contemporary Perspectives on language policy and literacy instruction in Childhood Education, New York: Information Age Publishing Inc.

Schmidt, R. (2000). Language and policy and identity politics in the United States, New York, Temple University Press.

Shohamy, E. (2006). Language policy: hidden agendas and new approaches, New York: Routledge.

Simpson, B. (2009). The American Language: The Case Against the English- only Movement, New York: Brandon Simpson.

Wodak, R., & Corson D. (1997). Language policy and political issues in education, Netherlands: Kluwer Academic Publishers.