Abstract

In this report, we present our findings on a group project in Team building with real-world simulation of soft skills necessary to build a high performance winning team. As a core subject of organisational management, any team building effort consists of several success attributes: guidance, collaboration, focussing on the process, network-building, openness, diversity, risk-taking, involvement of people, etc. This paper presents a clear, analytical framework within which we seek to consolidate essential concepts of team work as applied to real-world problems. The problem discussed in this paper is in the format of a case study and encompasses allied themes of risk management and economic analysis. The outcome of this project should be seen as an educational/motivational tool.

Introduction

Aims and objectives

Any team requires its members to display collaborative behaviour towards achieving common goals and vision. This report presents a detailed analysis of a simulated team building exercise with the following aims/objectives in mind:

- Understanding the common problems which creep up when a team comes together.

- Finding solutions to such problems using secondary literature.

- Learning about team building values which aid in the transition from a pseudo-team to a high-performance team.

- Application of above theories in a real project case study.

Background and Rationale

As undergraduate students at the University of _____, there were numerous occasions when we had to belong to some team or the other. Teamwork has always been an inseparable feature of classroom discussions, laboratory learning and practical training. Unfortunately, it’s not always possible to have a positive feeling about the way team discussions turn out. Many a times, serious personality differences between diverse members of a team leads to frustrations and hostility which for any team member, culminates in a general dislike for any situation involving team activities. In such occasions, team members do not even see eye to eye which hampers the progress of constructive work, leads to declining productivity and has long-term consequences on student morale.

Unpleasant experiences notwithstanding, all members of our group are knowledgeable about the real-world business scenario which would test our learning skills acquired from academia and look disfavourably upon any inability to successfully engage in team activities. All recruiting organisations today place a high emphasis on the applicant’s ability to see their role in a team. The very first question posed by an interviewer is, “what do you understand by teamwork?”

The rationale behind working on this project has a lot to do with the realisation that all of us shortly would find ourselves in various situations of teamwork at corporate level; our jobs, our career and our professional growth is inextricably linked to understanding the salient features of teamwork. This present research gives us a valuable opportunity to develop practical familiarity with different “technical terms” associated with teamwork.

Outline

This report is divided into the following chapters: Literature Review containing contextual critique of the subject matter at hand; Research Methodology containing relevant discussions on project initials, schedule and resource requirements; Analysis containing different aspects of project such as SWOT analysis, risk management and Occupational Health and Safety Management (OHSM) issues and finally, the Conclusion chapter provides an effective recapitulation of the main points at hand.

To fully illustrate discussions relevant to core topic, every effort has been made to correlate theoretical and practical aspects of this project. The project parameters solely depend on the criterion established in literature review and thus, provide enough opportunity to understand team-building skills from the point of view of a team leader. The concept of team work requires a fair deal of “enthusiasm towards the common goal” from all team-members (Michaelsen, Knight & Fink, 2002).

Literature Review

Overview

This chapter aims to understand various theoretical aspects of team work which have been used as reference to build various aspects of team-building strategy applied to the experiment design/group activity discussed in following chapters. The literature review section pursues the objective of measuring the author’s grasp of curriculum for given academic study (McMaster & Espin, 2007). The literature study aims to deliver precise knowledge inputs using arguments relevant to project proposal.

Theoretical Framework

According to Maddux and Wingfield (2003), the first step towards building a successful team lies in the ability of the team leader to “organise” and “plan” stated activities towards an eventual goal. The authors define the fundamental difference between a “team” and a “group” which is very important to our understanding of real-world scenarios. Whereas a group merely functions as the basis for family living, protection, work and recreation, a team is formed for a different purpose – to enhance the productivity of the group in terms of measurable impact (Maddux & Wingfield, 2003).

Another difference lies in the fact that a group’s functioning may vary anything between chaotic and unorganised whereas a team cannot afford to have such luxuries – a team must always be organised and disciplined to perform its roles as per its full expectations (Maddux & Wingfield, 2003).

The last difference lies in the way the member of a team perceives himself– the focus is always on the result and team benefits (Mchugh, 1997). However, in case of a group, the attention is shunted to individual interests only. A team member has to show the inclination to rise above petty self-interests and consider the benefits accrued to the team as a whole (Mchugh, 1997). This is made possible only through a willingness to overlook personality differences and have a clear focus on actions and strategy (Mchugh, 1997). Having understood the core principles of what constitutes a successful team, let’s understand a good procedure of building team work which lead to definite success in the aspirations for achievement:

- Building Motivation: Any new project which doesn’t have shared enthusiasm by every member of the team is bound to fizzle out in no time. Team-members should agree on the importance of a project for the overall well-being of every individual thereby developing a keen aspiration for results (Quick, 1992).

- Developing Trust and Collaboration: Team leaders should set an example for the remaining team by inculcating values in them which bespeak of transparency and honesty (Quick, 1992). Team members need to develop full faith and trust in the common pursuits of the team. Collaboration should be the norm instead of competition and team members should support one another in forging closer bonds for the overall benefit of the team (Quick, 1992). Trust and motivation are two indispensable assets of a successful team and should be inspired by the team leader.

- Conflict Resolution: Conflicts are at the heart and soul of an effective team-building process and should be accepted as a natural way of progressing ahead (Quick, 1992). Talented teams thrive in an atmosphere of participation and consensus which always reflects in their process of decision-making (Sewell, 1998). Most conflict issues in an amateur team arise due to personality/character differences wherein team members resort to personal attacks which vitiate the overall atmosphere of the working team (Mears & Voehl, 1994). To overcome any problems arising due to unavoidable conflicts, it is the team leader’s responsibility to assuage acrimonious feelings and nurture positive qualities in the team (Mears & Voehl, 1994).

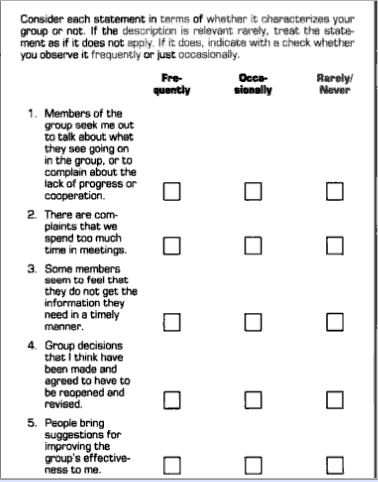

- Creativity and Effectiveness in Team Building: No team can develop solutions to difficult problems without a clear focus on nurturing new ideas/decisions and use group problem solving techniques. It consists of the following key steps: keeping the group small, announcing the meeting in advance, using a round robin to collect people’s ideas and encourage people to discuss ideas with the group, not the originator (Quick, 1992). Various diagnostic tools (Figure 1) can be used to keep a tab on team members’ behaviour concerning each other. The group diagnosticator as shown in Figure 1 can be used by team members to keep a tab on each other primary activities and thus, enable different people to achieve in advance solutions to impending problems.

- Power base: Many groups fail because of a lack of understanding of proper distribution of power for the effective team building exercise (Fiore, 2008). When the power base erodes, it leads to chaos and confusion hence, successful teams should always allow a clear hierarchy of power to allow decision-makers more freedom in dealing with eventual solutions (Fiore, 2008). It is the responsibility of the decision-maker to consult other members of the team for their inputs/suggestions which enable development of the creative thinking process. To successfully translate power functions of a team, team members should allow greater degrees of freedom for open-ended discussions, free exchange of thoughts and ideas and proper consultation with one and all concerned.

Having discussed the core concepts of team roles as applied to diverse situations, a question arises as to the application of these concepts. The basic strategy of team building activities is to promote team games as a successful way to achieving the major functions of a team. A team game involves a series of activities which allow the use of team attributes among team members and is thus, necessary to build and sustain the team (Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp & Gilson, 2008). Extending the use of necessary team attributes to develop and sustain a positive team requires a clear vision of activities in the know. Here is what a regular team game will consist of:

- Break-down of all activities into simple, systematic sub-routines: Each complex task can be divided into several sub-routines for the overall benefit of every member of the team (Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp & Gilson, 2008). This simplification can lead to brainstorming for core skills of every member in the team.

- Assigning role to team-members: The team leader must assign a unique role to every team member based on his/her aptitude and interests (Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp & Gilson, 2008). To ensure team members are satisfied with the pool of choice, the team leader may further choose to describe task functions in an easy-to-understand way. The goal of establishing hierarchical selection early on appeals to every member of the team (Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp & Gilson, 2008). Division of work according to unique human skills is the most fundamental aspect of proper team work management.

- Develop a learning environment: It’s unrealistic to expect team members to be aware of all issues which concern the team –it’s better to develop conditions facilitating a learning environment where every team member gets a unique opportunity to hone his/her skills according to needs and demands specified by the team (Mathieu, Maynard, Rapp & Gilson, 2008). The learning environment should also be a conduit for the exchange of free ideas. Indeed, given the chance to allow people to foster learning habits, many choose to decline the exchange when the environment is not conducive for it. Team leaders should keep the momentum of learning going because it’s believed a “learning team” is also a “successful team”.

- Performance and Rewards: While collaboration is the watchword here, many successful teams prefer its members to compete against each other in a healthy spirit (Quigley, Tekleab & Tesluk, 2007). Fostering healthy competition between different team members promotes high performance and should be strongly encouraged. It is often seen that competitive tendency brings out the winner in even among the most undervalued teams (Quigley, Tekleab & Tesluk, 2007).

Gaps in Literature

While the research study addresses several major issues connected with team building, a few problems could not be addressed:

- No description of real sample games: The team game chosen by our group was simplistic and did not require any extensive description.

- Use of preliminary methods in arriving at final data.

- The size of the team (4 members) was too small for any significant study of attributes such as power base relationships.

Research Methodology and Design

Overview

In this chapter, we shall discuss various aspects of project initiation, controls and results attributable to detailed project development. To closely understand research design, let us discuss the tasks and sub-routines connected with them. This chapter aims to discuss all relevant research design parameters as applied to our group project as a successful team. The elementary concepts of a high performance team, as discussed in previous chapter have been applied in this experiment to reach a clear conclusion on the points mentioned thus.

Research Design

The team was consisting of four members, all students at the same department in the University of ___. After gathering at a central place, we chose a simple mathematical game based on a Lego house. The task chosen was to assemble various 104 Lego bricks in pre-conceived patterns to complete a missing figure in the shortest possible time. The phenomena was to be observed over some time of 10 days with the hope of recording consisting improvement in performance with each passing day.

As team leader, I took the responsibility of saving daily logs for the activities. The objective was to draw from our experience in the theoretical framework and consistently collaborate to achieve our target of minimising Lego assembly time each day. A stop watch was used to keep track of time being spent on the project. The data was simply recorded using pencil logs and later developed into scalable routines. As described in theory, the task routines were broken down into the following components (refer previous chapter):

- Each team member was expected to concentrate on only their individual space which meant no pushing, shoving, jostling etc. Team members were advised to stay in control over their excitement and energy.

- As a thumb-rule, each sample day we built a new Lego-pattern based on common agreement. The idea was to achieve consistently good performance in recorded time without repeating the same pattern over and again.

- The research activity chosen could be called as “research in design” because of time-based dependence on various research parameters. The results would justify the means.

Research Schedule and Resource requirements

Continuing from previous section, the research activity chosen was simply based on impromptu collaboration between four members of the team for a common performance act. The resources were minimal and the actual game was played for 10 times at regular intervals for all participants. The following schedule was chosen based on the procedure described in theory:

Day 1: Break-down of all activities into simple, systematic sub-routines and assigning role to team-members: – This was achieved by dividing the entire assembly unit into colour-coded Lego bricks. The bricks were divided into four different colours: red, blue, green and yellow. Each person was assigned his/her unique colour combination. Even though it appeared somewhat difficult, the onus was on team-members to place their bricks in the grid according to their own best judgement and communicate/collaborate with members having bricks of different colours. The overall intention was to avoid time wasting and confusion due to arguments between various members of the same team. Each member was asked to share their information using verbal gestures so as not to disturb the concentration of other players. An outsider was selected to keep a tab on the stop watch for time calculation purposes.

Day 2-10: Developing a learning environment: Since, the Lego-building activity consists of versatile applications in innovative design, the task of team members was further modified into learning from experience. With each passing day, members were expected to be more knowledgeable about their game positions and learning from past mistakes. At the end of each day, we would sit down and discuss our strategies for the next round.

Day 2-10: The Actual Game period

Day 11: Performance and Rewards – The best performer among the group was marked/noted for each day’s performance and complimented for their resourcefulness. The final day event recognised the importance of “star performers” and a token cash prize was announced. This building of incentive was seen with active enthusiasm by all members of the team. The complete breakdown of schedule is shown in below figure:

Fig.2: Schedule recorder for various activities in given period.

Analysis

Overview

In this chapter, we shall discuss various aims/objectives findings and discussions derived from previous chapter. The aim of discussing these findings is to understand the role of team-building (and earlier theories) on the goals/research objectives at hand. In trying to understand these goals, our analysis will consist of following discussions: SWOT analysis, economic analysis, risk management issues and conclusions of the team.

SWOT analysis

SWOT is a highly useful methodology used to get a simplistic overview of the strengths and weaknesses of any management exercise (Bloodgood & Bauerschmidt, 2002). After a 10-day trial period, the following SWOT analysis was developed for the 4-member team:

Strengths

- Effective communication strategy worked. Members listened to each other and positively cared about the other person’s opinion. In general, there were no major conflict issues between different members. The team-building focused on a solutions approach to handling various conflicts.

- Proactive communications between various members of the group. Good compatibility on issues of speed and efficiency. All members understood their roles perfectly and there was little cause for conflict.

Weaknesses

Some members of the team were not skilled enough to understand hand gestures quickly. This cost us considerable time in a few of the observations recorded (see Table 1). This disadvantage was offset by building of positive team values which enabled each member to make extra effort in working out things.

Table 1: Time taken to finish activity (Lego Circles).

Opportunities

As is shown in Table 1, the team’s response time to the problem reduced considerably from 42 minutes to 34 minutes, a consistent gain recorded over 5 days.

Threats

No significant threat was conceived in the project activity.

Economic analysis of Project

The following economic analysis has been prepared as part of the project’s impact on several economic criteria. It should be known this project did not have any cost bearings on the participating team members. Still, several economic criteria can be used to describe the events:

- Multi-tasking: The project tested each team member’s ability to perform more than one task diligently and with effective impact. I, as team member was simultaneously engaged in co-ordinating the exercise and motivating my team to excel. Other members of the team did their part to ensure every step is taken to reduce average time for the game. Taking notes, forming quick mental associations, developing free thinking strategies were part of the ritual.

- Maximum utilisation of resources in fixed supply: From the very beginning, there was no doubt in the fact that the Lego bricks which came with unique designs were limited in initial supply. Each team member had to use his/her imagination to ensure no mismatch occurred during the assembly and consequent problems generated due to resources in fixed supply (Preston, 2005). With experience (i.e. by 10th day), all members were able to picturise their optimum path in ensuring all bricks got assembled without causing shortage. There were occasions when these goals could not be met because the bricks were already assembled inside and so, the entire structure had to be dismantled causing considerable time delay. Luckily, it could be compensated by suitable arrangements in project research design.

Risk Management

The following risks were measured as part of the overall project. The fall-out of any of these risk criterion would have only meant an increase in assembly time for the overall Lego structure. Thus, the risk context established is “increase in assembly time for overall Lego structure”. Most risk sources were internal to the environment (Dorfman, 2007) which refers to any faulty arrangement of Lego building blocks in the assembly line. To mitigate risks, the following criterion were chosen:

- Mapping out the process (Dorfman, 2007): The process, as discussed earlier was mapped out using the colour code for bricks (each participating member selected their colour). This ensured there was no resulting confusion in the final assembly and each team member could perform his/her job without interference from another member.

- Scenario analysis (Dorfamn, 2007): Several alternative scenarios were discussed in strategy to ensure no combination of Lego bricks creates a sorting problem. Bricks of similar shape and design were lumped together to achieve a realistic possibility of getting quick and easy brick combinations. In the inevitable scenario the wrong categories of bricks came in view as a result of chance, team members were advised to remember the sequence in which identical shapes appeared. With the end of repetitive experimentation, this concept was memorised in the best possible way, therefore eliminating all possibility of risk. To defeat chances of unfortunate combinations, team members were advised to communicate their intuitive gestures as quickly as possible. The eventual application of scenario analysis allows us to achieve a realistic risk assessment project in this report.

Conclusion

Summary

These are the major highlights of this assignment report corresponding to every aim/objective outlined in the study:

- Understanding the common problems which creep up when a team comes together. The problems identified in both theory and experiment are: conflict resolution, power distribution (hierarchy), risk management and personality clashes between various team members

- Finding solutions to such problems using secondary literature. Several literature sources (books and journals) were selected to achieve realistic solutions to the problems raised in the study. The four effective solutions discussed are: break-down of all activities into simple, systematic sub-routines; assigning role to team-members; developing a learning environment and finally, rewards for good performance and active contribution to team efforts

- Learning about team building values which aid in the transition from a pseudo-team to a high-performance team. Several team building values were discussed chief among them motivation among team members, trust and collaboration, creativity and efficiency etc. The most salient feature of good team-work is the ability of individual member to overcome his/her self interests in favour of team’s interests.

- Application of above theories in a real project case study. All above theories were tested in a real-term team activity (a game which consisted of forming random assemblies using LEGO structures over a period of 10 days). The corresponding experiment results were later analysed for risk management, SWOT analysis and economic analysis in addition to corresponding with team building figures.

Thus, it can be seen every conceivable effort has been made to answer aims/objectives of present research.

Recommendations

The following recommendations are made for further study:

- Use of critical path method (C.P.M.) which is a very important project management tool in coordinating various aspects of scheduling in the study.

- Coordination with more game activities since they reinforce essential concepts of team work in a practical, easy-to-understand way.

- The use of diagnostic tool for log-keeping in complex aspects of studying this report (Figure 1).

References

Bloodgood, J.M. & Bauersmith, A., 2002, “Competitive Analysis: Do Managers Actually CompareTheir Firms to Competitors”, Journal of Managerial Issues, Vol.14.

Dorfman, M., 2007, Introduction to Risk Management and Insurance, Prentice-Hall.

Fiore, S.M., 2008, “Interdisciplinary as Teamwork: How the Science of Teams can Inform Team Science”, Small Group Research, 39 (3), 410-476.

Quick, T.L., 1992, Successful Team Building, AMACOM (American Management Committee).

Quigley, N.R., Tekleab, A.G. & Tesluk, P.E., 1st Oct 2007, “Comparing Consensus and Aggregation-based Methods of Measuring Team-level Variables: The Role of Relationship Conflict and Conflict Management Processes”, Organizational Research Methods, 10 (4): 589-608.

Maddux, R.B. & Wingfield, B., 2003, Team Building: An Exercise in Leadership, Business and Economics.

Mathieu, J., Maynard, M.T., Rapp, T. & Gilson, L., 2008, “Team Effectiveness 1997-2007: A Review of Recent Advancements and a Glimpse into the Future”, Journal of Management, 34 (3), 410-476.

Mchugh, P.P., 1997, “Team-based Work Systems: Lessons from the Industrial Relations”, Human Resource Planning, Vol.20.

McMaster, K. & Espin, C., 2007, “Technical Features of Curriculum-Based Measurement in Writing, Journal of Special Education, Vol.41.

Mears, P. & Voehl, F., 1994, Team Building: A Structured Learning Approach, CRC Press.

Michaelsen, L.K., Knight, A.B., & Fink, L.D., 2002, Team-Based Learning, Praeger.

Newstrom, J.W. & Scanell, E.E., 1997, The Big Book of Team Building Games, Mc-Graw Hill Professional.

Preston, M.R., 2005, “Introduction to Economic Analysis”, Caltech Institute of Technology, Vol.23 (7).

Sewell, G., 1998, “The Discipline of Teams: The Control of Team-based Industrial Work Through Electronic and Peer Surveillance”, Administrative Science Quarterly, Vol.43