Introduction

The purpose of this study was to investigate the relation between sex, social status and temperament in a sample of preschool-aged children. Sociometric interviews were conducted with 182 children (92 boys and 90 girls). Status groups of popular, rejected, neglected, controversial and average children were identified according to previously established criteria. Teachers rated children’s temperament Results indicated that rejected children displayed a more difficult temperament than popular children in terms of higher activity levels, higher distractibility and lower persistence.

Both rejected and neglected children were rated as displaying lower adaptability and more negative mood than popular children. Boys were also rated as more active, more distractible and less persistent than girls. Results are discussed in terms of the relevance of particular temperament dimensions to successful social functioning for boys and for girls.

Consideration of the contribution that temperament might make towards children’s social competence and social status within the peer group has stemmed from the recognition of particular individual differences that appear, at least in part, to be constitutionally based and that reflect stylistic patterns of behavior. While adaptive or maladjustive outcomes are clearly not dependent on the contribution of temperament alone, there is evidence that individual differences in temperament qualities, such as activity level or approach/withdrawal, may be related to children’s social functioning and adjustment within the peer group (Farver & Branstetter, 1994; Mobley & Pullis, 1991; Stocker & Dunn, 1990).

Research with preschoolers has indicated that individual differences in temperamental characteristics may influence the adjustment children make to the preschool setting, the responses they make to their peers and the quality of their relationships with other children (Farver & Branstetter, 1994; Keogh & Burstein, 1988; Mobley & Pullis, 1991; Stocker & Dunn, 1990).

In general, children with easy temperaments, defined as approachful, adaptive and positive in mood (Thomas & Chess, 1977) have been found to respond prosocially to peer distress (Farver & Branstetter, 1994), have more positive and interactive relationships with friends and peers (Keogh & Burstein, 1988; Stocker & Dunn, 1990) and be rated as behaviorally adjusted to the preschool environment in terms of cooperation and persistence (Mobley & Pullis, 1991). In contrast, children with difficult temperaments appear to have relationships that are more problematic with their peers and are more likely to exhibit socialization and behavioral problems (Fabes , Shepard, Guthrie, & Martin, 1997; Mobley & Pullis, 1991).

Although there is evidence to suggest that individual temperamental characteristics may be linked to social adjustment and to frequency of socialization problems, the relationship between temperament, sex and social status has not been explored fully with respect to preschool-aged children. While some previous research has revealed clear sex differences in the display of temperamental characteristics identified as difficult (e.g., Farver & Branstetter, 1994; Mobley & Pullis, 1991; Sanson, Prior, Smart, & Oberklaid, 1993), whether temperamental characteristics are differentially related to social status for boys and for girls is unclear.

For example, there is some evidence that the temperament dimension of arousability may be negatively related to peer status for girls, whose play tends to be more sedentary than boys, yet positively related to peer status for boys, at least in early adolescence (Bukowski, Gauze, Hoza, & Newcomb, 1993). Thus, the aim of the present study was to examine sex and social status dif ferences in temperamental characteristics for preschool-aged children.

On the basis of present research it was expected that, in contrast to rejected children, popular children would exhibit fewer of those temperamental characteristics identified as difficult such as high activity levels, high distractibility, and negative mood. Although a difficult temperament may be predictive of low peer status for both boys and girls, it was expected that not only may boys be more likely to display difficult temperaments than girls, but that contextual features such as the differing interactional styles and norms for behavior that exist within boys’ groups and within girls’ groups may mediate the relationship between temperamental characteristics and social status.

Given the importance of positive peer relationships for children’s concurrent and future adjustment, examination of the linkages between temperamental characteristics, sex and social status appears to be important in understanding the influence and functional significance that temperament may have with respect to behavioral individuality and social adjustment.

Method

Participants

The sample consisted of 182 preschool children (mean age 62.4 months, SD = 4.22) from eleven suburban, community-based preschools serving lower to upper middle class families in Queensland, Australia. The sample included 92 boys and 90 girls. The children were predominately Caucasian with only three children of Asian origin and one Aboriginal child.

Procedure

Sociometric Status Classification. In the present study, sociometric data were collected through a combination of positive nominations and a rating scale. This procedure, developed by Asher and Dodge (1986), involves the substitution of a lowest play rating score for a disliked score which is obtained if a negative nomination method is used. Prior to commencing sociometric testing, photographs were taken of all children for whom parental permission had been given to participate in the research. The use of photographs increases the reliability of the sociometric measure for preschool-aged children.

Sociometric interviews were conducted individually during the second term of the school year. Children were first asked to select photographs of the three children with whom they most liked to play (positive nomination). Selected children were given a score of 1 for each time they were nominated. Next the participants were asked to rate all the children on a 3-point scale according to how much they liked to play with them by posting their photographs into one of three boxes. Depicted on the boxes were a happy face, a neutral face, and a sad face.

Children were advised that the happy face meant they liked to play with that child a lot, the neutral face that they liked to play with that child a little bit or sometimes, and the sad face that they did not like to play with that child. Children whose photographs were placed in the box with the happy face received a rating of three; in the box with the neutral face, a rating of two; and in the box with the sad face, a rating of one.

For each child the following scores were computed: (a) number of positive nominations (L score), (b) number of low play ratings (LPR score), (c) a social preference score (SP) based on subtracting the number of low play ratings (LPR) from the number of positive nominations (L), and (d) a social impact score (SI) computed by combining the number of low play ratings (LPR) and the number of positive nominations (L). These scores were converted into standardized scores for each sex within each preschool class.

Using the procedure outlined by Asher and Dodge (1987), children were classified into sociometric groups as follows: popular (L score greater than 0, LPR score less than 0 and SP score greater than 0), rejected (L score less than 0, LPR score greater than 0 and SP score less than -1.0), neglected (L score less than 0, LPR score less than 0 and SI score less than -1.0), controversial (L score greater than 0, LPR score greater than 0 and SI score greater than 1.0) and average (SP score between -.05 and.05 an d SI score between -.05 and.05).

Classification resulted in 26 popular children (12 boys, 14 girls), 22 rejected children (12 boys, 10 girls), 24 neglected children (13 boys, 11 girls), 11 controversial children (7 boys, 4 girls) and 33 average children (13 boys, 20 girls). All remaining children (35 boys and 30 girls) were classified as other.

Child Temperament. Teachers completed the 23 item Teacher Temperament Questionnaire (TTQ) developed by Keogh, Pulls and Cadwell (1982) which is a short form of the 64 item Thomas and Chess (1977) Teacher Temperament Questionnaire. The TTQ incorporates the eight temperamental dimensions used in the Thomas and Chess scale and describes behaviors related to specific dimensions of temperament which might typically be observed by teachers (e.g., Child sits still when a story is being told or read; When with others this child seems to be having a good time). Teachers were asked to rate on a 6-point scale, ranging from 1 (rarely) to 6 (almost always) the degree to which children displayed specific behaviors.

The authors of the TTQ identified three factors in the measure, which they labeled Task Orientation, Personal-Social Flexibility and Reactivity. Keogh and colleagues (1982) reported that the three factors demonstrated high internal consistency (Cronbach’s alpha =.94,.88 and.62, respectively). However, as the same temperament structure may not fit the data for all ages covered by the questionnaire (3 to 7 years) or for different populations of children, the use of a factor structure derived from the data of the population in question is preferable for research purposes. Therefore, a factor analysis of the items was conducted to identify the relevant temperament dimensions for this sample.

Results

Principal Axis Factor Analysis

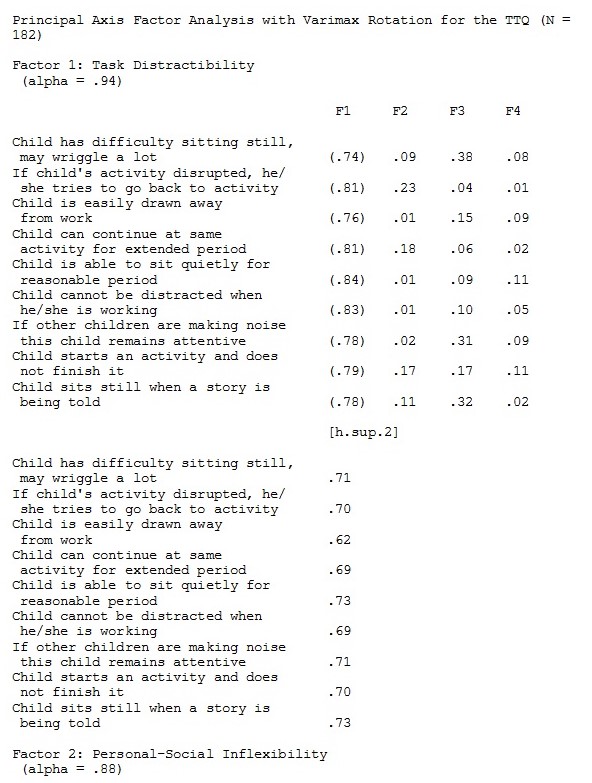

The subscale structure of this measure was confirmed with a principal axis factor analysis of the 23 items on the TTQ. A four-factor solution with orthogonal (VARIMAX) rotation afforded the simplest, interpretable structure and explained 67% of the variance. Given the sample size, a cut-off level for factor loadings was set at.40 (Stevens, 1996). All items had a factor loading which met this criterion with no cross loading of items across factors. The factor loadings for each item, item communalities and percentage of variance accounted for by each factor are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Factor One contained nine items, accounting for 26% of the variance, and was similar to Keogh et al.’s (1982) factor of Task Orientation. Items loading on this factor reflected the dimensions of activity, persistence, and distractibility. Factor Two contained eight items, accounting for 20% of the variance, and was similar to Keogh et al.’s (1982) factor of Personal-Social Flexibility. Items loading on this factor reflected the dimensions of approach/withdrawal, positive mood, and adaptability.

Factor Three contained four items, accounting for 12% of the variance, and was similar to Keogh et al.’s (1982) factor of Reactivity. Items loading on this factor reflected the dimensions of intensity and negative mood. The fourth factor, accounting for 9% of the variance consisted solely of two threshold of response items, which had loaded on Keogh et al.’s (1982) Reactivity factor. As interpretation of factors defined by only two variables is questionable, the items on the factor Threshold of Response were omitted fr om further analyses.

Although differing slightly from Keogh et al.’s (1982) three-factor structure, the items in this analysis clustered in logical and interpretable ways into three factors of Task Orientation, Personal-Social Flexibility and Reactivity. High mean scores on each factor represent a less desirable rating in terms of temperament. Thus, high scores on Task Orientation indicate ratings of low persistence, high activity and high distractibility; high scores on Personal-Social Flexibility indicate ratings of negative mood, low adaptability and low levels of approach; and high scores on Reactivity indicate ratings of negative mood and high intensity.

As high scores on Task Orientation and Personal-Social Flexibility represented low levels of Task Oriented behavior and low levels of Personal-Social Flexibility respectively, these factors were renamed Task Distractibility and Personal-Social Inflexibility to more clearly reflect the direction of the ratings. Thus, low scores on all factors denoted more positive attributes and high scores more negative behaviors.

The appropriateness of this factor structure for boys and girls was assessed by separate factor analysis for each sex. The resultant factor solutions were virtually identical and reflective of the solution for the total sample. Factor scores were calculated by summing the ratings for the item defining each factor. Reliability (Cronbach’s Alpha) of the factor scores for Task Distractibility, Personal-Social Inflexibility and Reactivity was.94,.88, and.77, respectively.

Sex and Social Status Differences

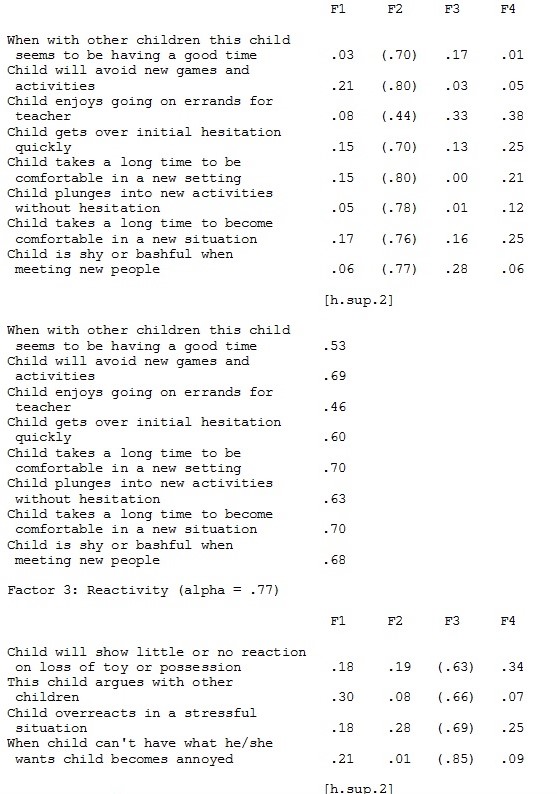

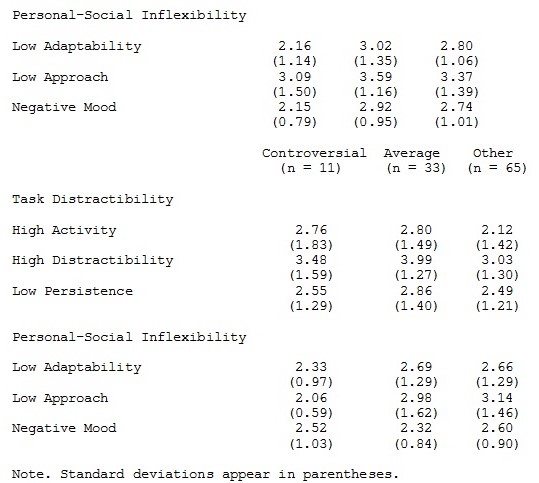

A MANOVA was conducted in which sex and social status served as independent variables. Dependent measures were the factor scores for Task Distractibility, Personal-Social Inflexibility and Reactivity. Means and standard deviations related to the dependent measures are presented in Table 2.

Using Wilks’ lambda statistic, significant mean effects were found for sex, F (1,170) = 8.29, p <.0005, and social status, F (5,170) = 2.38, p =.003, but not for the sex by social status interaction, F (5,170) = 1.43, p =.127. Univariate tests revealed significant sex differences along the dimensions of Task Distractibility, F (1,170) = 19.70, p <.0005, and Reactivity, F (1,170) = 9.14, p =.003. Results indicated that boys exhibited higher Task Distractibility and Reactivity than girls.

Table 2.

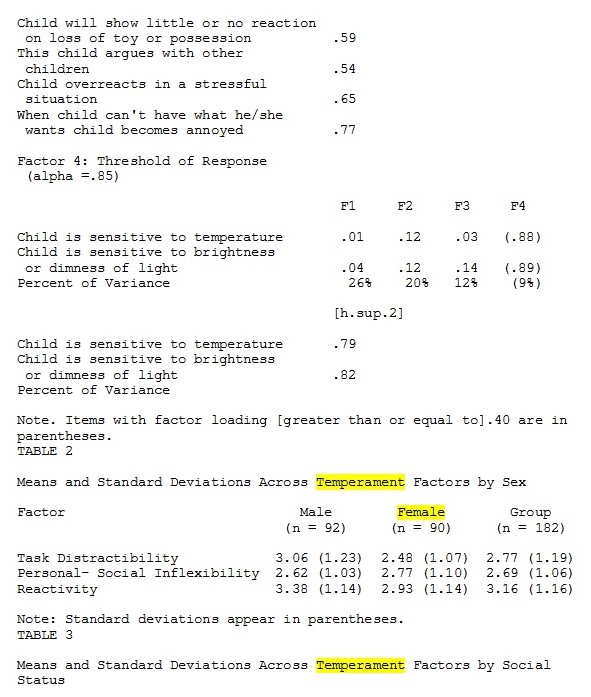

Univariate tests with respect to social status (see Table 3 for means and standard deviations) revealed significant social status differences along the dimensions of Task Distractibility, F (5,170) = 4.24, p =.001, while the dimension of Personal-Social Inflexibility approached significance, F (5,170) = 2.04, p =.077. Post hoc analyses using Duncan’s multiple range test revealed significant differences between both popular children and children classified as other and rejected and average children on the dimension of Task Distractibility.

Table 3.

Specifically, compared to popular children and other children, rejected children and average status children were rated as exhibiting high Task Distractibility. Popular and other children were rated similarly on this dimension. There were no other significant differences between social status groups on Task Distractibility.

Post hoc comparisons with respect to Personal-Social inflexibility revealed a significant difference between popular children and both rejected and neglected children on this dimension indicating that, compared to popular children, rejected and neglected children were rated as exhibiting higher Personal-Social Inflexibility. There were no other significant differences between status groups on this dimension.

Sex and Social Status Differences on Dimensions within Factors

Although use of factors consisting of clusters of similar items reflecting more global characteristics or traits is common when analyzing questionnaire data, caution must be used when examining group differences using constellations of characteristics such as Task Distractibility. Several authors (e.g., Coie, Dodge & Kupersmidt, 1990; Hymel, Bowker, & Woody, 1993) have pointed out the difficulty of interpreting the meaning of aggregate scores comprised of distinct variables. To the extent that different characteristics within each large factor may be differently associated with sex or social status, conclusions based on analysis of factors on their own might be erroneous.

Given the potential value of both approaches (see Hymel, Bowker, & Woody, 1993) initial analyses examined subgroup differences across aggregated scores based on the results of a factor analysis. Further analyses presented here considered subgroup differences in the specific dimensions underlying each of the more global factors. The purpose o f these analyses was to ascertain whether the identified sex and/or social status differences between groups were present for all aspects of the relevant dimensions. The dimensions included in these analyses were those related to factors on which significant differences were found.

Specifically, Task Distractibility and Reactivity with respect to sex differences and Task Distractibility and Personal-Social Flexibility with respect to social status differences. Two-tailed t tests were used to test for differences within these dimensions.

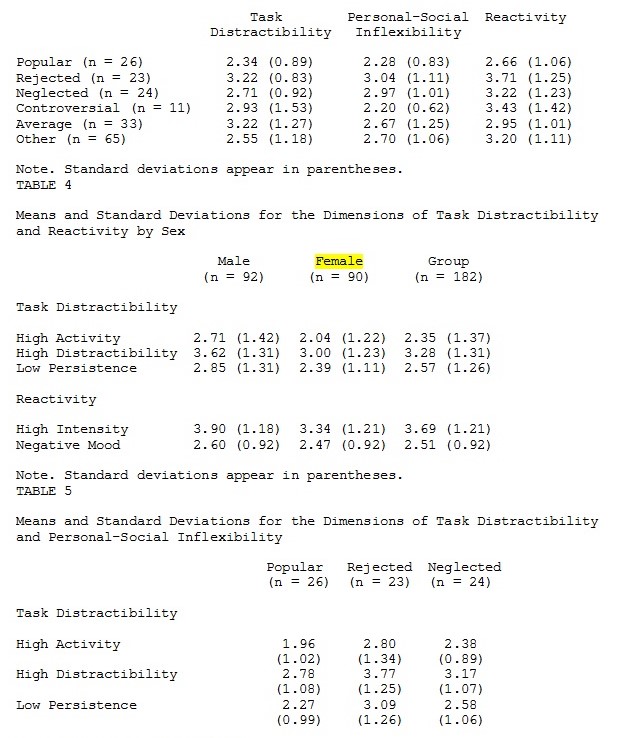

With respect to the sex differences on the dimensions within the factors of Task Distractibility and Reactivity, two-tailed t tests revealed girls were more likely to exhibit lower Task Distractibility in terms of lower activity levels, t (180) = 3.42, p =.001, lower distractibility, t (180) = 3.26, p =.001, and higher persistence, t (180) = 2.59, p.010, while boys were more likely to show high Reactivity in terms of higher intensity, t (180) = 3.18, p =.002, but not more negative mood. Means and standard deviations with respect to these dimensions are presented in Table 4.

Table 4.

With respect to social status differences on the dimensions within the factor of Task Distractibility, two-tailed t tests revealed that, compared to popular children, rejected children were rated as exhibiting high Task Distractibility in terms of higher activity rates, t (47) 2.48, p =.017, higher distractibility, t (47) = 2.96, p =.005, and lower persistence, t (47) 2.42, p =.019.

Average status children also differed significantly from popular children on this dimension in terms of higher activity, t (57) = 2.45, p =.017, and higher distractibility, t (57) = 3.86, p <.0005, but not lower persistence, t (57) = 1.82, p =.075. Rejected and average children also differed significantly from children classified as other.

Table 5.

Specifically, children classified as other were rated as exhibiting lower activity rates than both rejected, t (86) = 2.00, p =.049, and average children, t (96) = 2.21, p =.030, and lower distractibility than rejected, t (86) 2.36, p =.020, and average children t (96) = 3.48, p =.001. Means and standard deviations with respect to the dimensions within Task Distractibility and Personal-Social Inflexibility are presented in Table 5.

Two-tailed t tests with respect to the dimensions within the factor of Personal-Social Inflexibility revealed that, compared to popular children, rejected children were rated as exhibiting high Personal-Social Inflexibility in terms of lower adaptability, t (47) = 2.43, p =.019, and more negative mood, t (47) = 3.10, p =.003. Neglected children also differed significantly from popular children on the dimensions within this factor in terms of lower adaptability, t (48) = 2.05, p =.046, and more negative mood, t (48) = 2.31, p =.025. Popular children did not differ significantly in their rates of approach or withdrawal from either rejected children, t (47) = 1.31, p =.198, or neglected children, t (48) =.68, p =.502.

However, controversial children were rated as significantly different from rejected children, t (32) = 4.12, p <.0005, neglected children, t (33) 2.97, p =.005, and other children, t (74) = 2.41, p =.018, with respect to levels of approach and withdrawal. Controversial children also differed from popular children on this aspect of Personal-Social Inflexibility, t (35) = 2.19, p =.035, although not on ratings of adaptability or mood. Specifically, controversial children were rated as more likely to approach than rejected, neglected, other, or popular children. There were no other significant differences between status groups on the dimensions within this factor.

Discussion

Previous research has indicated that temperamental patterns such as high activity level and patterns of approach and withdrawal may play a part in social competence and adjustment within the peer group (Farver & Branstetter, 1994; Mobley & Pullis, 1991; Stocker & Dunn, 1990).

The present results support and extend these previous findings by indicating that temperamental characteristics appear to be directly related to children’s social status within the peer group. In contrast to expectations, there were no significant interactions between sex and social status with respect to temperamental characteristics. Findings with respect to sex differences will be discussed first.

Sex Differences

Past research has produced mixed results with respect to sex differences in temperamental characteristics with several studies reporting no significant differences between preschool-aged boys and girls (e.g., McDevitt & Carey, 1978; Mobley & Pullis, 1991; Sanson et al., 1993; Simpson & Stevenson-Hinde, 1985; Wright Guerin & Gottfried, 1994).

However, the results of the present study confirm intuitive notions regarding sex differences in expression of temperamental characteristics for preschool-aged children. Specifically, boys were rated by teachers as higher on Task Distractibility (more distractible, more active and less persistent) than girls. Boys were also rated as more intense than girls although not more likely to display negative mood (Reactivity).

While the dimension of Task Distractibility appears to be particularly important for behavioral adjustment to a preschool or school environment (Sanson et al., 1993), previous research has indicated that behavioral problems such as aggression or noncomplian ce, exhibited more often by boys, may be more closely linked to characteristics such as high intensity (Mobley & Pullis, 1991). Thus, the present findings provide support for the proposition that there are clear sex differences in temperamental characteristics at preschool age that may place boys at greater risk for social difficulties.

If, as results reported by Sanson et al., 1993; Sanson, Smart, Prior, Oberkiald, & Pedlow, 1994) suggest, temperament differences between boys and girls are negligible during infancy yet increase with age, the sex differences in temperament identified in the present study may be as much, if not more, a result of socialization into gender roles within both family and peer interactions as biological differences between boys and girls.

Given that social role stereotypes appear quite early on, and that socialization processes appear to be heavily implicated in the development of aggressive or antisocial behavior (Perry, Perry, & Rasmussen, 1986; Sanson et al., 1993), it is important to recognize that early social learning experiences may play a large role in the development of childhood temperament.

Social Status Differences

With respect to social status differences, there were significant differences between popular children and both rejected children and average status children along the temperament dimension of Task Distractibility. Specifically, children identified as rejected by their peers were rated by teachers as showing higher activity rates, higher distractibility and lower persistence than popular children while children classified as average status were rated as showing higher activity rates and higher distractibility but not lower persistence than popular children.

Thus, while rejected children do not appear to differ from average children with respect to Task Distractibility, low activity rates, low distractibility and high persistence appear to be linked to popular social status for preschool-aged children. Interestingly, children classified as other were rated similarly to popular children on the dimension of Task Distractibility and as significantly different from both rejected and average children in terms of lo wer activity rates and lower distractibility.

The dimension of Personal-Social Inflexibility also emerged as an important discriminator between social status groups with both rejected and neglected children being rated as displaying significantly higher Personal-Social Inflexibility in terms of lower adaptability and more negative mood than popular children. These results are in line with previous research that has identified Personal-Social Inflexibility (or flexibility) as related to children’s success in peer socialization (Mobley & Pullis, 1991; Stocker & Dunn, 1990) and friendship status (Farver & Branstetter, 1994).

Although, interestingly, rejected and neglected children did not differ significantly from popular children with respect to rates of approach or withdrawal, rejected, neglected, popular and other children were all rated as significantly different from controversial children on this aspect of Personal-Social Inflexibility. Specifically, controversial children were rated as displaying higher levels of approach and lower levels of withdraw al than children in rejected, neglected, popular or other groups.

Previous research has indicated that controversial children display behavior that represents a combination of the behavioral patterns shown by rejected and popular children. For example, in a meta-analytic review of the behavioral correlates of sociometric status, Newcomb, Bukowski, and Pattee (1993) concluded that while controversial children displayed levels of aggression similar to those exhibited by rejected children, they had other prosocial qualities which protected them from exclusion from the peer group.

The present results support the proposition that the elevated levels of approach with respect to social interaction displayed by controversial children may ameliorate their more negative qualities enabling them to maintain a level of social acceptance denied to rejected children. Although research into the behavioral characteristics of controversial children has been hampered in the past due to the low numbers of children classified into this group, further research into the reasons controversial chil dren are not rejected, despite their aggressive behavior, may improve our understanding of the phenomenon of peer rejection.

Conclusion

The strong links between temperamental characteristics and social status evident in the present findings suggest, as Brownell and Hazen (1999) propose, that individual temperamental characteristics might be more directly translated into individual differences in styles of social interaction during early childhood than in later school years.

While individual differences in peer competence among older children may be more a function of complex interactions between temperamental characteristics and social experiences, during the early childhood years, temperament may make a large contribution towards both the quantity and the quality of children’s interactions with their peers.

Thus, a child initially rejected by his or her peers due to temperamental characteristics may fail to develop the effective interpersonal skills necessary for mature and competent social behavior. The present results therefore indicate that intervention programs for children at preschool age need to take into account the particular temper amental styles, which appear to be associated with rejection in early childhood.

As models of social competence emphasize the ongoing interactions between individuals and the environment, competent behavior must include the ability to generate behavioral responses, which match the situational requirements of the social environment (Wine & Smye, 1981).

The temperament differences in Task Distractibility between boys and girls identified in the present study appear to be relevant to adjustment both within the peer group and, more broadly within the preschool environment (Mobley & Pullis, 1991). Thus, future research into the social learning experiences of young boys which appear to interact with early temperamental characteristics to place boys at greater risk for the development of social difficulties would appear to be well worthwhile.

References

Asher, S. R., & Dodge, K. A. (1986). Identifying children who are rejected by their peers. Developmental Psychology, 22(4), 444-449.

Brownell, C. A., & Hazen, N. (1999). Early peer interaction: A research agenda. Early Education and Development, 10(3), 403-413.

Bukowski, W. M., Gauze, C., Hoza, B., & Newcomb, A. F. (1993). Differences and consistency between same-sex and other-sex peer relationships during early adolescence. Developmental Psychology, 29(2), 255-263.

Coie, J. D., Dodge, K. A., & Kupersmidt, J. B. (1990). Peer group behaviour and peer group social status. In S. R. Asher & J. D. Coie (Eds.), Peer rejection in childhood (pp. 17-59). Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Fabes, R. A., Shepard, S. A., Guthrie, I. K., & Martin, C. L. (1997). Roles of temperamental arousal and gender-segregated play in young children’s social adjustment. Developmental Psychology, 33(4), 693-702.

Farver, J. A. M., & Branstetter, W. H. (1994). Preschoolers’ prosocial responses to their peers’ distress. Developmental Psychology, 30(3), 334-341.

Hymel, S., Bowker, A., & Woody, E. (1993). Aggressive versus withdrawn unpopular children: Variations in peer and self-perceptions in multiple domains. Child Development, 64(3), 879-896.

Keogh, B. K., & Burstein, N. D. (1988). Relationship of temperament to preschoolers’ interactions with peers and teachers. Exceptional Children, 54(5), 456-461.

Keogh, B. K., Pullis, M. E., & Cadwell, J. (1982). A short form of the teacher temperament questionnaire. Journal of Educational Measurement, 19(4), 323-329.

McDevitt, S. C., & Carey, W. B. (1978). The measurement of temperament in 3-7 year old children. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 19, 245-253.

Mobley, C. E., & Pullis, M. E. (1991). Temperament and behavior adjustment in preschool children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 6, 577-586.

Newcomb, A. F., Bukowski, W. M., & Pattee, L. (1993). Children’s peer relations: A meta-analytic review of popular, rejected, neglected, controversial, and average sociometric status. Psychological Bulletin, 113 (1), 99-128.

Perry, D. G., Perry, L. C., & Rasmussen, P. (1986). Cognitive social learning mediators of aggression. Child Development, 57, 700-711.

Sanson, A., Prior, M., Smart, D., & Oberklaid, F. (1993). Gender differences in aggression in childhood: Implications for a peaceful world. Australian Psychologist, 28(2), 86-92.

Sanson, A. V., Smart, D. F., Prior, M., Oberklaid, F., & Pedlow, R. (1994). The structure of temperament from age 3 to 7 years: Age, sex and sociodemographic influences. Merrill Palmer Quarterly, 40 (2), 233-252.

Simpson, A. E., & Stevenson-Hinde, J. (1985). Temperamental characteristics of three to four-year-old boys and girls and child-family interactions. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 26 (1), 43-53.

Stevens, J. (1996). Applied multivariate statistics for the social sciences. New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Stocker, C.,& Dunn, J. (1990). Sibling relationships in childhood: Links with friendships and peer relationships. British Journal of Developmental Psychology, 8, 227-244.

Thomas, A., & Chess, S. (1977). Temperament and development. New York: Brunner/Masel.

Wine, J. D., & Smye, M. D. (1981). Social competence. New York: Guilford.

Wright Guerin, D., & Gottfried, A. W. (1994). Developmental stability and change in parent reports of temperament: A ten-year longitudinal investigation from infancy through preadolescence. Merrill-Palmer Quarterly, 40 (3), 334-355.