Abstract

It has been acknowledged that children’s exposure to diverse food textures at an early age is beneficial for their development. Young children learn about new foods and develop eating behaviours that have an effect on their dietary preferences at an older age. This study explored the use of food texture descriptions on the packaging of products targeting preschool children and sold at Tesco and ASDA in Northern Ireland.

It is found that smooth was a dominating food texture term, but it was mainly associated with foods targeting children under one year old. Crispy and crunchy were the second most frequent food texture terms found on the package. It is suggested that the attention paid to food texture is insufficient as a substantial part of product packages do not include any food texture descriptors. Although this study is limited to the analysis of products available from two supermarkets, it still identifies the current trends. The lack of standardised descriptions of food texture is apparent and should be addressed in order to ensure clarity for consumers. Food producers, governmental agencies, health-related institutions, and consumers should collaborate to ensure the development of the framework regulating the provision of data concerning food texture.

Introduction

The governments of the UK and Northern Ireland (NI) declare their commitment to ensuring proper public health, which has an impact on many aspects of food, including food production. Governmental agencies suggest numerous types of guidance regarding texture, food labelling, the content of different elements, packaging, as well as marketing and children’s access to certain products (Theurich 2018). Extensive research into the eating behaviours of young children suggests that commercial foods have a substantial influence on the development of a considerable “proportion of their diet” (Tedstone et al. 2019, p. 4). The dietary patterns of infants and toddlers also have a direct effect on their body weight and dental health.

Manufacturers of foods produced for infants and toddlers often market their products as addressing the target population’s developmental needs and preferences. However, it has been found that many packaged foods are characterised by rather a high concentration of sugar or other unhealthy components (Fuller 2016). For instance, Coyle et al. (2019) found that flavoured milk and yogurts produced for the UK and NI market held approximately twice the average amount of sugar of unflavoured items.

According to the results of a survey conducted by Hashem et al. (2018), the composition of biscuits, cakes, and other snacks was even more alarming as these foods often contained excessive amounts of sugar, and over 95% of cakes and 75% of biscuits had to receive ‘red’ label for this element (i.e. products with exceeded contents of sugar) in 2016. The content of nutrients within foods is well-researched, but other aspects also receive researchers’ considerable attention.

Texture and Children’s Development

Texture is an important feature of food that has a considerable effect on young children’s dietary habits (Kennedy et al. 2018). Green et al. (2017) emphasise that this food property is often overlooked in the production of complementary feeding items, although food texture can have an impact on children’s oromotor development. Children’s oromotor readiness is instrumental in their safe early feeding experiences, so the choice of food texture should be age-appropriate (Harris & Coulthard 2016; Harris & Shea 2018). In their study, Werthmann et al. (2015) explored food acceptance based on colour, smell, and texture among children aged 32-48 months old and reported that texture was the most influential factor.

The longitudinal study conducted by Jeltema et al. (2015) led to the development of a framework for understanding people’s textural food choices that is based on the role of mouth behaviour in the process of consumers’ food preferences and development. Nederkoorn et al. (2015) identified a correlation between children’s tactile sensitivity and picky eating. It was also found that children tended to dislike foods that seemed unpleasant when they touched them, which suggests that texture plays an important role in the development of children’s food preferences (Nederkoorn et al. 2018).

Food Production

The producers of foods aimed at young children work on the development of textures that would be favourably accepted among their target population and use texture descriptions on food packaging to attract potential new and retain loyal customers (Bublitz & Peracchio 2015). Governmental agencies and international institutions also pay specific attention to labelling and regulate certain norms, including general food descriptions (World Health Organisation [WHO] 2019).

For instance, Lal Dar and Light (2014) state that over half of all U.S. snack and bakery products have texture claims on their packages. Some of the common descriptions for this category of foods include soft, moist, crunchy, crispy, creamy, chewy, thin, smooth, thick, fluffy, tender, velvet, and silky (Lal Dar & Light 2014). It is also largely accepted that consumers may use different words to describe some products and textures, which poses some limitations to the effectiveness of packaging descriptions of food texture. It also makes consumers uncertain about the properties of products, which can have an impact on their choice (Lal Dar & Light 2014).

Project Aims and Objectives

The current situation in the UK and NI market reveals quite an alarming trend as food packaging is not detailed enough to meet the needs of customers. The need to expose young children to diverse textures have been justified, but customers still have no information regarding this important aspect of food (Lal Dar & Light 2014). It is also necessary to pay specific attention to snacks that play a significant role in meeting young children’s nutrient and energy needs.

This project aims at characterising the textural properties of a selection of ambient foods targeted for sale to preschool children in two supermarkets in Northern Ireland (Asda and Tesco). Therefore, it is beneficial to analyse the descriptions food producers choose as appealing to their customers, which can help in identifying certain preferences regarding food texture (Murray 2017).

The focus of this study is on snack products that target young children. Some packaged snacks are often regarded as rather harmful foods. The research question is as follows: What are the most frequently utilised food texture descriptions on the packaging of snack products that target young children? The descriptions provided on food packages were analysed and were secondly compared to the common descriptors of food texture as employed in the scientific literature.

Methodology

The Creation of the Database of On-Package Texture Descriptions

A pre-existing database (the Queens’ Preschool Food and Ingredient Database included details of 245 packaged snacks aimed at young children as described online at the official websites of Tesco and ASDA operating in Northern Ireland. These retailers were chosen as they have the largest network nationwide and reach a wide audience characterised by considerable diversity. Tesco dominates the market of Northern Ireland with almost 35%, while Asda follows with a market share of over 17% (McDonald 2017). The product information of every product available from the official database was reviewed in order to identify exact words utilised to define food texture (see Table 1.A).

Table 1.A. Key Product Information in the Database.

Details of all information contained in the data base are described in Table 1.1a. The number of the identified words describing texture was 30, and each of these items was given a unique descriptor with an assigned value that ranged between 1 and 30 (see Table 1.1.A).

These codes were utilised to make the data analysis process more effective. The created numerical descriptors were employed for the analysis for convenience as it is more effective to use codes rather than words when analysing data (Elliott 2018). The products descriptions often contained several terms related to food texture, so several columns with the corresponding codes were created for each food item under consideration. For the purpose of the quality control, 10% of the entire number of the products included in this study (n245) was selected randomly (see Table 1A Appendix A). Overall, 25 food items were cross-checked in order to ensure the reliability of the findings.

Table 1.1.A. Generation of ID or Code to Characterise On-Packaging Description of Food Texture.

In order to avoid repetition and the use of invalid descriptions, the definitions of the corresponding words were reviewed. Some notions were merged as they denoted the broadly similar properties (for instance, crunchy and munching). Some terms were removed from the set of the analysed items as they did not refer to food texture (for example, zesty and tangy). After this procedure, the number of codes for texture descriptions was reduced from 30 to 11 codes (see Table 1.1 B). The quality control procedure mentioned above was utilised to ensure the validity of the aggregated list of food descriptions. Overall, 25 food texture descriptions were chosen randomly and cross-checked see Table 1B in Appendix A.

Table 1.1.B. Generation of Codes for the Final Aggregated On-Packaging Description of Food Texture.

The Creation of the Database of Literature Food Texture Descriptions

Prior to reviewing the descriptions given on products’ packaging, an extensive literature review was implemented. The definition of the notion of food texture was developed based on the current literature, and the corresponding food texture descriptors were singled out. Based on the identified food texture terms, 14 descriptors were selected and assigned numerical codes between 1 and 14 see Table 1.2.A.

Table 1.2.A. Codes Characterising Literature Food Texture Description.

A similar quality control procedure was undertaken. 25 items (10% of the total number of products under consideration) see Table 1c in Appendix A were chosen randomly and cross-checked. The number of developed codes (which was 14 initially) was reduced to 9 after the close analysis of the description (see Table 1.2.B). The quality control procedure mentioned above was applied to ensure the correctness and reliability of the findings. See Table 1D in Appendix A.

Table 1.2.B. Codes for Final Aggregated Literature Food Texture Description.

Data Analysis Procedure

Microsoft Excel can be employed to manage comparatively small sets of data and was utilised in this analysis (Watson 2015). For the purpose of this study, the frequency tool of Microsoft Excel was utilised to identify the most frequently used descriptions

- used on the actual food packaging and

- based on the description of texture from the scientific literature.

Food texture descriptions of several food groups were analysed. The following groups were considered: bars and rusks; infant, plain, and chocolate-coated biscuits; breadsticks and oatcakes; crackers; fruits (including dried and commercial pureed fruits); rice cakes and wafers; savoury and sweet extruded snacks; smoothies; and fruit-based sweets. The frequency of the use of some descriptions in terms of age groups was also analysed. The use of food texture descriptors for foods that target children under the age of 12 months and over a year was analysed.

Results

The Most Frequently Used ‘On-Pack’ Food Texture Descriptors

The frequency of use of terms associated with smoothness was high on the packaging of products aimed at young children (for more details on all (i.e. the disaggregated) of the food descriptors as listed on package, see Table 1 in Appendix B). The terms smooth/smooth no bits/no lumps or bits/puree appeared on 39% of packaging (see Table 2). In contrast, 64 items had packages with no specified food texture (see Table 2). Third most frequent category, was melt-in-your-mouth/melty/dissolve easily in your mouth/soften in little mouth with 31 uses (see Table 2). This category was followed by crispy/gentle crunch/crackers (mentioned 31 times) and crunchy/munching (employed 24 times). Gummy (3 uses), crumbly (3 occurrences), and thick/chunky (4 times used) were the least frequent (see Table 2).

The Most Frequently Used Descriptors in Terms of Literature on Food Texture

When the descriptors of the same foods were compared to the literature-based definitions of texture, the frequency of the use of food texture descriptions in literature was similar to the terms used on package. Smooth was utilised 93 times in terms of aggregated food texture descriptors (see Table 3) (see Table 2 Appendix B for more details regarding all food descriptions as listen in literature). In 61 cases, food texture was not specified, while the analysis of aggregated food texture descriptions indicated a more frequent use (64 times). The aggregated food texture terms analysis showed that thick is used 4 times, which was followed by silky (used twice).

Table 2. Frequency of Occurrence of Aggregated Food Texture Descriptions as Listed On-Pack in a Sample of Foods (n245) Targeted for Sale to Preschool Children in Northern Ireland.

Table 3. Frequency of Occurrence of Aggregated Food Texture Descriptions as Listed in Literature in a Sample of Foods (n245) Targeted for Sale to Preschool Children in Northern Ireland.

The Most Frequently Used Descriptors in Terms of Product Food Groups

The utilisation of the food texture descriptions as per product group was analysed (see Figure 1). As far as the aggregated list of on-pack food texture descriptions is concerned, the most commonly utilised terms were Smooth/Smooth no bits/No lumps or bits/Puree with 96 instances (see Table 2 Appendix C).

Smoothies and commercial pureed fruits are mainly described with this food texture term. The texture was not specified in 64 items throughout the majority of product categories, which was the second most frequent occurrences (for more details on all the food texture descriptors as per product group that are used on package, refer to Table 1and figure Appendix C). Food texture descriptors were provided in such food categories as sweet extruded snacks, crackers (including infant crackers), oatcakes, and breadsticks, and chocolate-coated biscuits.

The analysis of the aggregated food texture terms used in literature showed that the word smooth appears 93 times to describe commercial pureed fruits and smoothies (see Figure 2). Texture was not specified in 65 items, which was the second top description as per its frequency (see Table 2 Appendix D). Among the products with specified food texture were sweet extruded snacks, crackers (including infant crackers), oatcakes, and breadsticks, and chocolate-coated biscuits. The dominating description was followed by the terms crispy (33 occurrences), crunchy (22 instances), and soft (appeared 19 times) (for more details regarding the use of all food texture terms in literature in terms of product groups see Table 1 Appendix D and Figure 1 Appendix D for visual representation).

These words were found in such food groups as savoury and extruded snacks, infant biscuits, bars, and rusks, as well as fruit-based sweets. Silky was the least frequently utilised description and appeared only twice in rice cakes category.

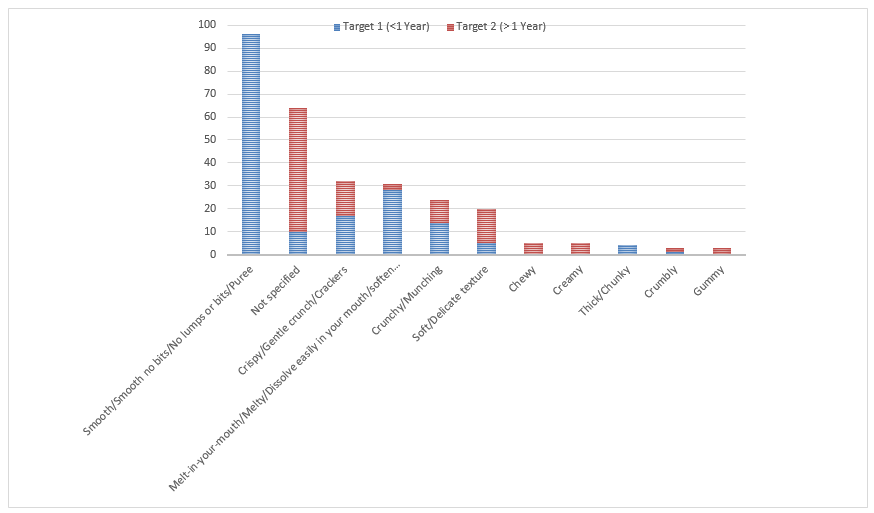

The Most Frequently Employed Descriptors in Terms of Children Age Groups

The occurrence of these descriptions was also analysed by age group i.e. as targeted to children under one year old (target 1) and those over one year old (target 2). The analysis of aggregated food texture descriptions as per age group indicated that smooth / smooth no bits / no lumps or bits / puree were the most frequently used terms (96 occurrences), and these were applied to target 1 products solely (see Figure 3). No texture description was provided on the package of 64 items, and 54 items out of these products target older children (see Table 2 Appendix E).

Commonly used terms were also crispy / gentle crunch / crackers that appeared on the package of both groups with 17 uses for target 1 group and 15 uses for target 2 group. More details concerning all food texture terms found on package as per target age groups are given in Table 1 Appendix E (also see Figure 1 Appendix E for visual representation of data). Such descriptors as melt-in-your-mouth / melty / dissolve easily in your mouth / soften in little mouth were almost equally frequent as the previous category, but they were mainly utilised for products targeting children under one year old.

The food descriptions as listed on literature revealed a similar trend regarding the occurrence on the package of products targeting children under and over one year old. Aggregated literature food texture descriptions revealed a similar trend concerning the use of the term smooth (see Table 2 Appendix F). This descriptor appeared 93 times and refers to the target 1 group only (see Figure 4). Food texture was not specified on the package of 64 items, and products targeting older children constituted the majority of such snacks (for more details regarding all the food descriptors as per target age group found in literature, see Table 1 Appendix F and Figure 1 Appendix F for visual representation of this data). Crispy and crunchy were employed on the package of foods targeting both age groups.

At that, crispy was used almost equally in both age groups with 17 occurrences in literature targeting children under one year old and 16 uses for the foods for older children (see Table 2 Appendix F). Crunchy revealed the same trend with 12 and 10 times employed on the package of foods for target 1 and target 2 groups respectively. The term soft was utilised quite frequently, but it prevailed on the package of products targeting older children. Chewy, creamy, and thick were rather infrequent and prevailed in some age groups (see Figure 4). Chewy and creamy were used five times each while silky was used only twice, and it was associated with foods targeting children under one year old.

Discussion

Top Food Texture Terms as per Age and Product Group

The analysis of the package of items targeting preschool children and sold at Tesco and Asda reveals certain trends regarding the use of food texture terms. Smooth (as well as associated descriptors smooth no bits / no lumps or bits / puree) is the most frequently utilised term, but it is mainly used with products targeting younger children. Crunchy and crispy are commonly inscribed on the package of the items targeting preschool children.

Snacks, rice cakes, wafers, fruit-based sweets, and biscuits are the product categories described with the help of the words crunchy and crispy. It is also noteworthy that researchers and manufacturers tend to use slightly different descriptors sets. Manufacturers’ list of food texture terms is wider, while descriptors found in the literature are more precise. Researchers employ standardised notions based on previous studies and existing guidelines provided by governmental agencies and international institutions.

Food Texture on Product Packaging and in Literature

People living in the UK and Northern Ireland are becoming increasingly conscious about health and healthy lifestyles, which affects their food choices and preferences (Hughes & Power 2018). Parents try to establish healthy diets to ensure their children’s healthy behaviours (Hughes & Power 2018; Heath 2016). Although snacks are rather popular in the markets of the UK and NI, people acknowledge the adverse effects this type of food can play on their or their children’s health. Many types of snack are considered unhealthy, and some types are preferred due to their positive (or neutral) health outcomes (Damen et al. 2019).

It has been acknowledged that packaging and labelling have quite a strong effect on the way products are perceived by consumers (Bailey 2016; Skaczkowski et al. 2016; Rebollar et al. 2017). In simple terms, food texture terms used on packs can develop certain expectations that transform into people’s perceptions of texture and taste (Bailey 2016). The review of the literature indicates that consumers and manufacturers do not have some standardised lists of food texture definitions, which leads to quite a loose understanding of the exact properties of the purchased product.

The research on food texture focusing on terms and definitions dates back to the middle of the twentieth century when scientists started working on the development of classifications and terminology related to food texture (Moskowitz & Jacobs 2017). Scientists often employed diverse methodologies and approaches, which led to the development of quite different definitions and terms (Chen & Rosenthal 2015).

One of the central issues related to the creation of classifications is wording as people place different meanings to similar notions, sensations, and phenomena (Liu et al. 2019; Diederich 2015). Moreover, on the international scale, it can be rather difficult to develop a standardised list of terms and definitions due to linguistic issues (Diederich 2015). Therefore, there is still a lack of an accepted set of terms and definitions regarding food texture in international standards (as well as country-wide research).

This gap may partially account for the difference between food texture terminology utilised by food manufacturers and mentioned in the scholarly literature (Skaczkowski et al. 2016). Food producers implement market research to address their business goals and increase sales. They tend to focus on people’s tastes and wording rather than scientific vocabulary due to their willingness to speak the language of their potential consumers, which is a common approach to selling products. This study unveils the difference between the descriptors used by food producers and the terms employed in literature. Such descriptors as gentle crunch or melt-in-your-mouth instead of crunchy and tender show that food manufacturers try to speak their consumers’ language rather than utilise the terms mentioned in literature.

The Role Parents Play in the Use of Food Texture Terms on Package

When developing their package design and data to be displayed, including food texture terms to be employed, food producers conduct various market researches to understand the driving forces of parents’ choices and preferences to make their products more attractive for their potential customers (Scrinis 2015). For instance, Russell et al. (2017) found that product visuals and rating stars were the most influential factors that affected parents’ choice.

It is also argued that parents’ concerns regarding their children’s health had an impact on the purchases they made, especially when it comes snacks (Moskowitz & Jacobs 2017; Pinto et al. 2017). Parents are also affected by the recommendations provided by numerous institutions and health-related organisations (Nicklaus et al. 2015; Pérez-Escamilla et al. 2019). Breastfeeding and complementary foods introduction recommendations are influential factors that have an impact on parents’ food choices (Koletzko et al. 2019).

Texture Preferences

It has been widely acknowledged and accepted that children should receive age-appropriate and diverse food as per its taste and texture (Tedstone et al. 2019; WHO 2019). The inappropriate exposure to new textures can result in picky eating behaviours (Emmett et al. 2018). Importantly, Ross (2017) claims that although parents tend to have a substantial effect on the development of food preferences and behaviours in their children, the latter also has an important role in the process.

During feeding, children may choose some products (tastes, colours, or textures) and ignore or refuse to eat others, which influences considerably the snacks children are given. The smooth texture is often a preferable choice with children under one year old, but this texture preference often persists at an older age (Ross 2017; Schwartz et al. 2018; Steele et al. 2014). The complementary foods are often smooth or liquid, since it is similar to breastmilk and is often readily accepted by children (Schwartz et al. 2018).

The results of this study suggest that smoothness is one of the preferred properties of food given to preschool children. It is noteworthy that this type of texture is described similarly by manufacturers, consumers, and researchers. Smoothness is one of the central texture types that are employed in marketing and research related to food texture preferences in young children (Campbell et al. 2017; James 2018). Snacks targeting preschool children are dominated by smooth foods as this texture is regarded as age-appropriate and is positively accepted by toddlers (Campbell et al. 2017). This dominant position is acknowledged and accepted by marketers who employ this description to promote their products and make them more attractive to potential customers.

This research also unveiled another existing trend related to food texture of snacks that target young children. Crispy and crunchy are also widely used texture descriptions provided on the package of snacks produced for pre-schoolers. As mentioned above, the provision of diverse foods is beneficial for young children, especially those older than six months (Simione et al. 2018). Parents are encouraged to introduce new textures to ensure their children’s proper oromotor development and the establishment of a healthy diet. Crispy and crunchy are often regarded as close notions with a slight difference related to the products consumed (Liu et al. 2019). This study indicates that these terms are equally used in marketing (on the package) and in academia (literature). Crunchy and crispy have become widely used in many spheres and have obtained a definite meaning shared by many people, including manufacturers, consumers, and researchers (Diederich 2015). These descriptions are often associated with specific foods (Liu et al. 2019; Diederich 2015). In this study, savoury and extruded snacks, as well as rice cakes and wafers, were mainly described with the help of these terms.

Crispy and crunchy are utilised to describe foods targeting different age groups, which suggests that this texture type has a more diverse audience as compared to smooth textures that tend to target younger children. Crunchy and crispy foods become a preferable type of foods in older children. The introduction of such textures is regarded as favourable due to its positive effect on children’s health outcomes as the consumption of vegetables and the intake of hard foods is associated with a lower risk of the development of obesity (McCrickerd & Forde 2015; Pereira & van der Bilt 2016).

As mentioned above, manufacturers have identified the most recent trends in people’s perceptions and preferences, as well as concerns, and develop their marketing strategies accordingly. The textures that are most valued by consumers are present on the packaging to attract more customers. In their turn, parents show their positive attitude towards this texture as they are influenced by various health-related institutions that promote diversity in young children’s diets.

Another important finding of this research is a high occurrence of products with not specified texture, which shows that manufacturers are still insufficiently aware of the role texture plays in people’s choices and the way certain data on packaging affects people’s buying decisions. Consumers reveal certain interest in the review of food texture when buying food, but this interest is rather low (Johnson 2015).

The lack of the description of texture also unveils the gaps associated with available guidelines and regulations related to food production and marketing. These findings are consistent with the current research as it is acknowledged that food production lacks certain precision regarding packaging and labelling even for foods targeting young children (Johnson 2015; Lease et al. 2016). It can be necessary to trace the changes in food texture descriptions during recent years to identify the shifts in consumers’ and manufacturers’ attitudes towards food texture.

This Study’s Strengths and Limitations

One of the primary contributions of this study is the identification of the most frequent food texture descriptions provided on the package of products targeting young children. It is apparent that smooth, crispy, and crunchy are the most preferred textures. This study also unveiled the lack of attention to food texture in food production as manufacturers should be more precise when describing their products. Another important outcome of this research is the analysis of the use of specific food texture terms in food production and research. The study attempted to bridge the gap between the research related to food texture and food production industry by analysing the terminology employed in both areas.

The limitations of this study include the focus on two supermarkets, which can have an adverse effect on the generalisability of data. Furthermore, the actual intake of the products is not considered as the availability of products is the inclusion criterion. The representativeness of the products included in this study is limited by the supermarket’s business operation as other retailers can offer items with other packaging.

As for future directions of the research, it is possible to concentrate on the development of a standardised vocabulary that could be used by food producers and scientists. The developed classification may be used to develop guidelines that would be provided by the corresponding international institutions. These guidelines may also become a bridge between scientific terminology and the definitions employed by food producers.

Conclusion and Future Direction

In conclusion, it is necessary to note that the analysis of the packaging of foods targeting preschool children with the focus on two supermarkets in Northern Ireland shows the prevalence of snacks that are characterised by smooth texture. Such foods mainly target children under one year old. Crispy and crunchy are other food texture descriptors appearing on the package of snacks for young children. However, a considerable proportion of analysed items had no food texture descriptors. It is important to make sure that food manufacturers provide comprehensive information regarding their products, and food texture is one of the important properties that can affect people’s choices.

This study has unveiled the existing trends regarding the use of food texture descriptions on the package of snack products targeting preschool children. Although increasing attention to food texture descriptions is apparent, food manufacturers still fail to provide sufficient information regarding the matter. Consumers are becoming more health-conscious, which makes them make wiser choices considering such properties as food texture.

Based on the findings of this study, several areas for improvement and further research can be identified. First, it is essential to create a comprehensive list of standardised descriptions of food texture that could be utilised by food manufacturers. This guideline should be evidence-based and grounded on the existing research, which is rather extensive. It is also critical to ensure food producers’ compliance with the created standards. Governmental agencies will safeguard the proper implementation of the policy aimed at the introduction of a standardised framework for food manufacturers.

Another area to concentrate on is raising people’s awareness of the role texture plays in children’s development and the establishment of their dietary habits that will persist in their adulthood. Consumers have a direct influence on food manufacturers, so the increased interest of the former to food texture and improved labelling (and packaging) will be instrumental in creating new patterns in the food industry. The prevalence of products characterised by smooth texture may indicate that parents do not actively introduce diverse foods, which can have adverse effects on children’s health. Therefore, most attention should be paid to this area, and parents have to understand the health outcomes of the dominance of smooth foods in the diets of children under one year old.

Although this study is quite limited in scope as only two supermarkets were included, it can become the background for further investigations. The similar methodology can be used to consider food texture description on products sold from major retailers nationwide. It is also important to pay more attention to consumers’ preferences and choices concerning food texture of the products for their young children.

Finally, it is necessary to facilitate the research related to food texture since it will be instrumental in the promotion of healthy foods. Food producers will be able to provide healthier foods that are becoming increasingly attractive for modern consumers. Governmental agencies and international health-related institutions should be involved in the process through the provision of investment, development of guidelines, and the overall promotion of healthy lifestyles.

Reference List

Bailey, RL 2016, ‘Influencing eating choices: biological food cues in advertising and packaging alter trajectories of decision making and behavior’, Health Communication, vol. 32, no. 10, pp. 1183-1191.

Bublitz, MG & Peracchio, LA 2015, ‘Applying industry practices to promote healthy foods: An exploration of positive marketing outcomes’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 68, no. 12, pp.2484-2493.

Campbell, CC, Wagoner, TB & Foegeding, EA 2017, ‘Designing foods for satiety: the roles of food structure and oral processing in satiation and satiety’, Food Structure, vol. 13, pp.1-12.

Chen, J & Rosenthal, A 2015, ‘Food texture and structure’, in J Chen & A Rosenthal (eds), Modifying Food Texture, Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, pp. 3-24.

Coyle, DH, Ndanuko, R, Singh, S, Huang, P & Wu, JH 2019, ‘Variations in sugar content of flavored milks and yogurts: a cross-sectional study across 3 countries’, Current Developments in Nutrition, vol. 3, no. 6. Web.

Damen, FWM, Luning, PA, Fogliano, V & Steenbekkers, BLPA 2019, ‘What influences mothers’ snack choices for their children aged 2–7?’, Food Quality and Preference, vol. 74, pp.10-20. Web.

Diederich, C 2015, Sensory adjectives in the discourse of food: a frame-semantic approach to language and perception, John Benjamins Publishing Company, Philadelphia, PA.

Elliott, V 2018, ‘Thinking about the coding process in qualitative data analysis’, The Qualitative Report, vol. 23, no. 11, pp. 2850-2861. Web.

Emmett, PM, Hays, NP & Taylor, CM 2018, ‘Antecedents of picky eating behaviour in young children’, Appetite, vol. 130, pp.163-173.

Fuller, GW 2016, New food product development: from concept to marketplace, 3rd edn, CRC Press, Boca Raton, FL.

Green, JR, Simione, M, Le Révérend, B, Wilson, EM, Richburg, B, Alder, M, Del Valle, M & Loret, C 2017, ‘Advancement in texture in early complementary feeding and the relevance to developmental outcomes’, in RE Black, M Makrides & KK Ong (eds), Complementary feeding: building the foundations for a healthy life, Vevey/S. Karger AG., Basel, pp.29-38.

Harris, G & Coulthard, H 2016, ‘Early eating behaviours and food acceptance revisited: breastfeeding and introduction of complementary foods as predictive of food acceptance’, Current Obesity Reports, vol. 5, no. 1, pp.113-120.

Harris, G & Shea, E 2018, Food refusal and avoidant eating in children, including those with autism spectrum conditions: a practical guide for parents and professionals, Jessica Kingsley Publishers, Philadelphia, PA.

Hashem, KM, He, FJ, Alderton, SA & MacGregor, GA 2018, ‘Cross-sectional survey of the amount of sugar and energy in cakes and biscuits on sale in the UK for the evaluation of the sugar-reduction programme’, BMJ Open, vol. 8, no. 7, pp.1-13.

Heath, MR 2016, ‘The relevance of food structure – a dental clinical perspective’, in JMV Blanshard & JR Mitchell (eds), Food structure: its creation and evaluation, Elsevier, London, pp. 1-6.

Hughes, SO & Power, TG 2018, ‘Parenting influences on appetite and weight’, in JC Lumeng & JO Fisher (eds), Pediatric Food Preferences and Eating Behaviors, Elsevier, London, pp.165-182.

James, B 2018, ‘Oral processing and texture perception influences satiation’, Physiology & Behavior, vol. 193, pp.238-241.

Jeltema, M, Beckley, J & Vahalik, J 2015, ‘Model for understanding consumer textural food choice’, Food Science & Nutrition, vol. 3, no. 3, pp.202-212.

Johnson, D 2015, ‘Legislation and practices for texture-modified food for institutional food’, in J Chen & A Rosenthal (eds), Modifying Food Texture, Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, pp.223-238.

Kennedy, GA, Wick, MR & Keel, PK 2018, ‘Eating disorders in children: is avoidant-restrictive food intake disorder a feeding disorder or an eating disorder and what are the implications for treatment?’, F1000Research, vol. 7. Web.

Koletzko, B, Bührer, C, Ensenauer, R, Jochum, F, Kalhoff, H, Lawrenz, B, Körner, A, Mihatsch, W, Rudloff, S & Zimmer, K 2019, ‘Complementary foods in baby food pouches: position statement from the Nutrition Commission of the German Society for Pediatrics and Adolescent Medicine’, Molecular and Cellular Pediatrics, vol. 6, no. 1. Web.

Lal Dar, Y & Light, JM 2014, ‘Introduction’, in Y Lal Dar & JM Light (eds), Food Texture Design and Optimization, John Wiley & Sons, New York, NY, pp. 1-18.

Lease, H, Hendrie, GA, Poelman, AM, Delahunty, C & Cox, DN 2016, ‘A sensory-diet database: a tool to characterise the sensory qualities of diets’, Food Quality and Preference, vol. 49, pp.20-32.

Liu, YX, Cao, MJ & Liu, GM 2019, ‘Texture analyzers for food quality evaluation’, Evaluation Technologies for Food Quality, pp. 441-463.

McCrickerd, K & Forde, CG 2015, ‘Sensory influences on food intake control: moving beyond palatability’, Obesity Reviews, vol. 17, no. 1, pp.18-29.

McDonald, G 2017, ‘Tesco market share in north outstrips Sainsbury’s and Asda combined – survey’, The Irish News. Web.

Moskowitz, HR & Jacobs, BE 2017, ‘Consumer evaluation and optimization of food texture’, in HR Moskowitz (ed), Food texture: food science and technology, CRC Press, New York, NY, pp. 293-328.

Murray, RD 2017, ‘Savoring sweet: sugars in infant and toddler feeding’, Annals of Nutrition and Metabolism, vol. 70, no. 3, pp.38-46.

Nederkoorn, C, Jansen, A & Havermans, RC 2015, ‘Feel your food. The influence of tactile sensitivity on picky eating in children’, Appetite, vol. 84, pp.7-10.

Nederkoorn, C, Theiβen, J, Tummers, M & Roefs, A 2018, ‘Taste the feeling or feel the tasting: tactile exposure to food texture promotes food acceptance’, Appetite, vol. 120, pp.297-301.

Nicklaus, S, Demonteil, L & Tournier, C 2015, ‘Modifying the texture of foods for infants and young children’, in J Chen & A Rosenthal (eds), Modifying Food Texture, Woodhead Publishing, Cambridge, pp.187-222.

Pereira, L & van der Bilt, A 2016, ‘The influence of oral processing, food perception and social aspects on food consumption: a review’, Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, vol. 43, no. 8, pp.630-648.

Pérez-Escamilla, R, Segura-Pérez, S, & Hall Moran, V 2019, ‘Dietary guidelines for children under 2 years of age in the context of nurturing care’, Maternal & Child Nutrition, vol. 15, no. 3, pp.1-3.

Pinto, VRA, Freitas, TBO, Dantas, MIS, Della Lucia, SM, Melo, LF, Minim, VPR & Bressan, J 2017, ‘Influence of package and health-related claims on perception and sensory acceptability of snack bars’, Food Research International, vol. 101, pp.103-113.

Tedstone, A, Nicholas, J, MacKinlay, B, Knowles, B, Burton, J & Owtram, G 2019, Foods and drinks aimed at infants and young children: evidence and opportunities for action. Web.

Rebollar, R, Gil, I, Lidón, I, Martín, J, Fernández, MJ & Rivera, S 2017, ‘How material, visual and verbal cues on packaging influence consumer expectations and willingness to buy: the case of crisps (potato chips) in Spain’, Food Research International, vol. 99, no. 1, pp.239-246.

Russell, CG, Burke, PF, Waller, DS, & Wei, E 2017, ‘The impact of front-of-pack marketing attributes versus nutrition and health information on parents’ food choices’, Appetite, vol. 116, pp.323-338.

Schwartz, C, Vandenberghe-Descamps, M, Sulmont-Rossé, C, Tournier, C & Feron, G 2018, ‘Behavioral and physiological determinants of food choice and consumption at sensitive periods of the life span, a focus on infants and elderly’, Innovative Food Science & Emerging Technologies, vol. 46, pp.91-106.

Scrinis, G 2015, ‘Reformulation, fortification and functionalization: Big Food corporations’ nutritional engineering and marketing strategies’, The Journal of Peasant Studies, vol. 43, no. 1, pp.17-37.

Simione, M, Loret, C, Le Révérend, B, Richburg, B, Del Valle, M, Adler, M, Moser, M & Green, JR 2018, ‘Differing structural properties of foods affect the development of mandibular control and muscle coordination in infants and young children’, Physiology & Behavior, vol. 186, pp.62-72.

Skaczkowski, G, Durkin, S, Kashima, Y & Wakefield, M 2016, ‘The effect of packaging, branding and labeling on the experience of unhealthy food and drink: a review’, Appetite, vol. 99, pp.219-234.

Steele, CM, Alsanei, WA, Ayanikalath, S, Barbon, CEA, Chen, J, Cichero, JAY, Coutts, K, Dantas, RO, Duivestein, J, Giosa, L, Hanson, B, Lam, P, Lecko, C, Leigh, C, Nagy, A, Namasivayam, AM, Nascimento, WV, Odendaal, I, Smith, CH & Wang, H 2014, ‘The influence of food texture and liquid consistency modification on swallowing physiology and function: a systematic review’, Dysphagia, vol. 30, no. 1, pp.2-26.

Theurich, M 2018, ‘Perspective: novel commercial packaging and devices for complementary feeding’, Advances in Nutrition, vol. 9, no. 5, pp.581-589.

Watson, R 2015, ‘Quantitative research’, Nursing Standard, vol. 29, no. 31, pp.44-48.

Werthmann, J, Jansen, A, Havermans, R, Nederkoorn, C, Kremers, S & Roefs, A 2015, ‘Bits and pieces. Food texture influences food acceptance in young children’, Appetite, vol. 84, pp.181-187.

World Health Organisation 2019, Commercial foods for infants and young children in the WHO European Region. Web.

Appendix A

Table 1A. Quality Control of 10% of Food Description in On-Packaging of Food (n=245).

Table 1B. Quality Control of 10% of Food Description in Aggregated On-Pack of Food (n=245).

Table 1C. Quality Control of 10% of Food Description in Literature Texture of Food (n=245).

Table 1D. Quality Control of 10% of Food Description in Aggregated Literature Texture of Food (n=245).

Appendix B

Table 1. Frequency of Occurrence of Food Texture Descriptions as Listed On-Pack in a Sample of Foods (n245) Targeted for Sale to Preschool Children in Northern Ireland.

Table 2. Frequency of Occurrence of Food Texture Descriptions as Listed in Literature Texture in a Sample of Foods (n245) Targeted for Sale to Preschool Children in Northern Ireland.

Appendix C

Table 1. Supporting Table of Frequency of Occurrence of Food Texture Descriptions as Listed on On-pack as per Food Group in a Sample of Foods (n245) Targeted for Sale to Preschool Children in Northern Ireland

Table 2. Supporting Table of Frequency of Occurrence of Aggregated Food Texture Descriptions as Listed on-pack as per Food Group in a Sample of Foods (n245) Targeted for Sale to Preschool Children in Northern Ireland

Appendix D

Table 1. Frequency of Occurrence of Food Texture Descriptions as Listed on Literature Texture as per Food Group in a Sample of Foods (n245) Targeted for Sale to Preschool Children in Northern Ireland.

Table 2. Frequency of Occurrence of Aggregated Food Texture Descriptions as Listed on Literature Texture as per Food Group in a Sample of Foods (n245) Targeted for Sale to Preschool Children in Northern Ireland.

Appendix E

Table 1. Frequency of Occurrence of Food Texture Descriptions as Listed On-Pack as per Target Age Group in a Sample of Foods (n245) for Sale to Preschool Children in Northern Ireland.

Table 2. Frequency of Occurrence of Aggregated Food Texture Descriptions as Listed On-Pack as per Target Age Group in a Sample of Foods (n245) Targeted for Sale to Preschool Children in Northern Ireland

Appendix F

Table 1. Frequency of Occurrence of Food Texture Descriptions as Listed on Literature Texture as per Target Age Group in a Sample of Foods (n245) Targeted for Sale to Preschool Children in Northern Ireland.

Table 2. Frequency of Occurrence of Aggregated Food Texture Descriptions as Listed on Literature as per Target Age Group in a Sample of Foods (n245) Targeted for Sale to Preschool Children in Northern Ireland