Introduction

Six nations and sixty million people were put at risk by the death of once the fourth largest lake on earth. The Aral Sea is the epitome of human-environmental malpractice and one of the earth’s worst environmental catastrophes. Soviet-era mismanagement, transboundary water conflict issues, and rapidly worsening climate change have made the Aral Sea a thing of the past. UNESCO added the lake’s documents to the “Memory of the World Register.”

The Aral Sea is one of the ideal models for the connection between the well-being of an ecosystem and that of communities and economies dependent on it. Humans do not always manage to preserve the beauty of nature, and some of its phenomena deteriorate or become destroyed altogether. To prevent this, citizens of all countries must make every effort to save the wonders of the Earth and take responsibility for the destruction of forests, deserts, water, and other resources. The Aral Sea has many severe problems, and people have to try to solve them soon to save at least a part of its region.

Human activities, most importantly the careless handling of the irrigation project that drained the Aral Sea, are the primary causes of its decline. The water can only be preserved and restored by funneling back into it.

Objectives

- To identify and analyze the problems of the lake, its basin, and the entire region

- To discuss the causes and consequences of the lake’s destruction

- To evaluate the solutions proposed for ameliorating the consequences

Study Area

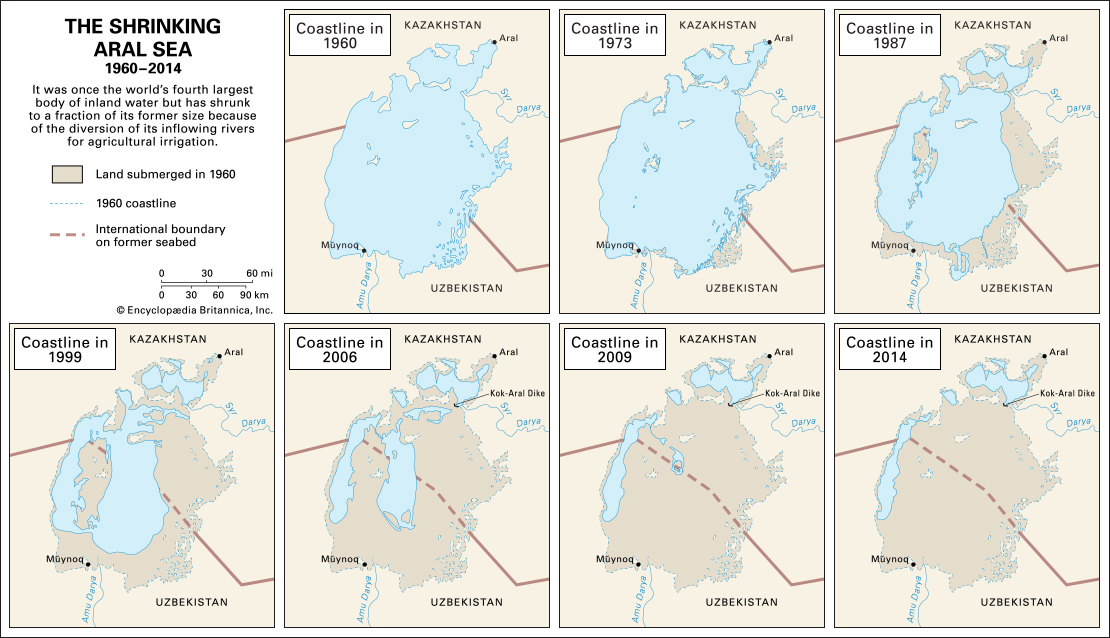

The Aral Sea was a sinking lake between Uzbekistan and Kazakhstan. Due to an irrigation program that drained water from it, it started drying up in the 1960s. Before the 1960s, the lake was the fourth-largest in the world and had an area of 26,300 sq ml. By 1997, it has split into four distinct lakes: the South Aral Sea, split into two parts, a small lake in the middle, and the North Aral Sea. In 2014, the eastern basin of the lake desiccated completely, and now it is called the Aralkum Desert.

Literature Survey

A lot of literature exists covering the damage of the lake, the consequences, and possible solutions to the problem. Dilbar et al. (2019) examine the issue of the Aral Sea and the possibilities of eliminating it. Micklin (2016) tries to predict the likelihood of saving the Aral Sea region through restoration. Many scholars have studied issues surrounding the Aral Sea including Aladin et al. (2019), Guo et al. (2016), Izhitskiy et al. (2016), and Kalimbetova et al. (2020).

People living in the lake basin struggle with a variety of problems, such as the death of the fishing trade and the lack of water with which to water crops (Izhitskiy et al., 2016, Micklin. 2016, Shukla, 2015). The extent of the damage was classified until the collapse of the Soviet Union, at which point the decay was already in an advanced state. Though complex, the roots of the disaster are now well understood and restoration efforts have been going on in the last few decades.

Causes of Aral Sea Shrinking

Historical geography suggests that the drying of the Aral Sea must have taken place previously. Millions of years ago, northern parts of Uzbekistan and southern parts of Kazakhstan were covered by a vast endorheic lake. The water receded gradually and highly saline soil plains were exposed leaving a few intermittent water bodies that became the Aral Sea. Evidence suggests that the lake has been completely or partially flooded more than eight times for the past ten thousand years. The role of rainfall variations in this flooding is unclear (Shukla, 2015). Recent shrinking which started in the 1960s is the focus of this paper. In the 1960s, the Aral Sea covered an area of 26,300 sq ml but by 2008, it covered only 1,270 sq mi (Dilbar et al., 2019). The water volume decreased by more than 90% and the concentration of salt contents increased five-fold (Dilbar et al., 2019). Over the last six decades, the lake has been gradually separating into smaller water bodies. The dried-up floor came to be known as Aralkum Desert.

There is a significant number of serious issues that destroy the lake and make the region poor. It has experienced rapid shrinking and desiccation since Soviet projects diverted its inlets (Dilbar et al., 2019). Though this project made agricultural activities successful in the area, it also divided the sea into several parts and made it much smaller. When the lake desiccated, fisheries and other economic activities the communities depended on collapsed. The water became saltier and polluted with pesticides and fertilizer, which is decimated fish and other aquatic life (Ogli & Qizi, 2019). The dust that was blowing from the exposed lakebed was poisoned and contaminated with agricultural chemicals (Micklin et al., 2016). It became a public health hazard, substantially affecting the health of the residents. The shrinking of the sea even influenced changed microclimates as winters became colder and summers drier and hotter.

Massive water withdrawals and technological advances are the main cause of basin-wide desiccation and shrinking. This is a terminal lake that depends on groundwater and river inflow to maintain surface levels. It is fed mainly by the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers but in the 1950s and 1960s, both rivers were used to channel water for irrigation purposes and as a result, the supply of water to the lake was greatly impeded (Shukla, 2015). This led to excess evaporation resulting in major imbalance and drastic shrinking in surface and volume of water. The Soviet Union regime embarked on a massive expansion irrigation scheme with an aim to

- Multiply the production of cotton

- Increase the production of fruits and vegetables

- Supply the Central Asian states with rice and export too

- Employ local people

To meet these objectives, massive amounts of water were diverted from the Amu Darya and the Syr Darya to irrigation schemes. In the 1960s, there were more than five million hectares of land in the lake’s basin under irrigation (Aladin et al., 2019). That figure would jump to 8.5 million hectares in 1990.

By 1990, Uzbekistan was the biggest producer of cotton globally. Cotton is still the main cash crop in that country accounting for approximately 17% of its exports. Many of the canals for purposes of irrigation during the Soviet era were poorly built allowing evaporation and leakage. It is estimated that 30 to 70% of water meant for irrigation went to waste (Shukla, 2015). This diversion and wastage of water from the river discharge led to drastic drops in the water feeding the Aral Sea. In some years, the lake received virtually no water inflows from the rivers. While agricultural production did increase, it was at a huge environmental cost. Sadly, the Soviets were well aware that the lake would disappear. They considered the existence of the lake an error in nature and knew it would eventually evaporate and shrink due to the irrigation scheme. The complete extinction of the Aral Sea has various disastrous outcomes for those residing in the Aral Sea Basin.

Consequences

The Aral Sea shrinking is a textbook case of ecosystem collapse and the epitome of environmental malpractice. The flora and fauna of the Aral Sea Basin have suffered greatly as the water disappeared. Inhabitants were reliant on the Aral Sea for water supply and economic activities such as fishing (Kalimbetova et al., 2020). The dry surface is covered with salt and toxic chemicals and worsening soil and water quality.

There is massive environmental degradation as salt from irrigation drainage water is partially returned to rivers to pass to downstream areas. This has increased land and water salinization. Increasing salinization threatens the livelihoods of millions of residents physically and economically. Erosion and sedimentation threaten freshwater regulation and allocation in the basin (Shukla, 2015). There is serious soil contamination from the overuse of chemical fertilizers. Biodiversity and wetlands have diminished and surrounding mountains have suffered from deforestation.

The drying of the lake has caused serious socio-economic and environmental consequences. There is a vast area that has now been turned into a desert as rivers flow through deltas and spring floods are virtually eliminated. The construction of storage reservoirs upstream has led to falling water surface levels in the Aral Sea and the intensification of the desertification process. The now largely barren land covering an area of more than fifty thousand square kilometers is characterized by dust and salt winds that are harmful to domestic animals by reducing their food supply (Aladin et al., 2019). The area’s climate has also experienced a shift from maritime conditions to desert conditions.

The shrinking of the Aral has had dangerous effects on the health of the population around it. Environmental and health experts call the Aral Sea Basin an ecological disaster zone. The airborne dust and salt contribute to the high prevalence of eye problems, respiratory ailments, and certain types of cancer. Contamination of drinking water from the massive irrigation project is to blame for typhoid, dysentery, tuberculosis, anemia, and hepatitis. Due to salt concentration in drinking water, kidney and liver diseases are widespread in the area. Other effects of the disappearance of the lake include the shortage of drinking water and an increase in unemployment in the fishing sector. Former fishing towns are today marveled at as ship graveyards. The main fishing port known as Aral lies several miles from the sea and its population has gone down dramatically as the main economic activity dies.

Solution

There has been multi-government and multiagency collaborations and effort to restore the Aral Sea with some results albeit slow ones. The recovery of the 1960s water levels requires cooperation from all countries whose rivers feed the lake. Attempts to revive the lake started in the late 1990s and there has been some success especially in Kazakhstan. A rudimentary dam built to save the North Aral Sea and sacrifice the South Aral Sea broke a few years later. In 2004, the World Bank financed the building of a new dam, and since then the North Aral Sea has been steadily improving its water coverage and volume. It has also recovered some of its aquatic fauna and evaporation has slowed. Water is now 15 km away from the city of Aralsk and it was one 50 km away (Plotnikov et al., 2016). Fishing is slowly resuming in the North Aral Sea and healthiness is slowly being restored.

With the current situation, the full recovery of the lake is not probable as the factors that led to the disaster are still existent. The area is still in a disaster state and the natural ecosystems have been destroyed to an extent that it is not suitable for human habitation. International efforts to restore the lake are expected to replenish Aral’s water, restore a stable ecosystem, decrease salt and dust by blowing, and improve the climate around the lake and its basin. Various solutions have been identified and some are carried out to an extent (Izhitskiy et al., 2016). These include improving the quality of irrigation canals, promoting economic activities that are non-agricultural upstream, improving cotton farming by using fewer chemicals during cultivation, and using the plant’s alternative species that utilize less water. Technology such as irrigation optimization and laser leveling has also been employed in varying degrees. Five nations have implemented the Aral Sea Basin Program since 1994 in different phases.

The Aral Sea basin countries, the international community, and multiple agencies have made various attempts to solve the issue of the drying lake and eliminate the consequences of the problem. For example, Aral Sea Basin Programs are aimed at stabilizing the basin’s environment and rehabilitating the disaster area around the sea (Kalimbetova et al., 2020). Moreover, possible reactions include using fewer agricultural chemicals on the cotton and improving the irrigation canals’ quality (Bekchanov et al., 2016).

These actions are of great importance and may help save the Aral Sea region. Large-scale restoration efforts have seen the resurgence of aquatic life in the North Aral Sea. The Syr Darya repair is ongoing to improve the quality of water and increase its flow. The future of the South Aral Sea has largely been abandoned but environmentalists are still campaigning for more effort to be put in. Uzbekistan, which relies heavily on cotton exports, is still using the Amu Darya river for irrigation. Plans are also underway for oil exploration in the South Aral seabed.

Conclusion

The Aral Sea disappearance disaster has fortunately led to the collaboration of nations and international bodies in the last few decades. Intergovernmental meetings and international conferences have been held to try and restore the lake. Countries in Central Asia can only realize unified development if they coordinate conflict of interests by regional and global collaboration. The Aral Sea and its basin is a highly complex ecological system that has been destroyed by the massive and reckless withdrawal of water from its two main sources. This has led to the making of one of the earth’s worst environmental catastrophes as the world watches.

The consequences have been dire and far-reaching as the environment takes vengeance on the humans as well as the innocent flora and fauna. The consequences of this destruction can be corrected through the restoration of the lake through a concerted effort from all stakeholders.

References

Aladin, N. V., Gontar, V. I., Zhakova, L. V., Plotnikov, I. S., Smurov, A. O., Rzymski, P., & Klimaszyk, P. (2019). The zoocenosis of the Aral Sea: six decades of fast-paced change.Environmental science and pollution research international, 26(3), 2228–2237. Web.

Bekchanov, M., Ringler, C., Bhaduri, A., & Jeuland, M. (2016). Optimizing irrigation efficiency improvements in the Aral Sea Basin. Water Resources and Economics, 13, 30-45.

Dilbar, Q., Polvonnazarovna, A. N., & Ugli, A. B. B. (2019). The problem of the Aral Sea and the Aral Sea Basin, its consequences and solutions. International Journal of Academic Pedagogical Research, 3(4), 46-47.

Guo, L., Zhou, H., Xia, Z., & Huang, F. (2016). Evolution, opportunity and challenges of transboundary water and energy problems in Central Asia.SpringerPlus, 5(1). Web.

Izhitskiy, A., Zavialov, P., Sapozhnikov, P. et al. (2016). Present state of the Aral Sea: diverging physical and biological characteristics of the residual basins.Sci Rep, 6. Web.

Kalimbetova, R., Mambetullaeva, S., & Allambergenova, F. (2020). Environmental problems of water supply of the population of the South Aral Sea region and protection of water resources. Journal of Critical Reviews, 7(8), 1784-1787.

Micklin, P. (2016). The future Aral Sea: Hope and despair. Environmental Earth Sciences, 75(9), 844.

Micklin, P., Aladin, N. V., & Plotnikov, I. (Eds.). (2016). The Aral Sea: The devastation and partial rehabilitation of a Great Lake. Springer.

Ogli, Z. O. T., & Qizi, A. F. A. (2019). Aral Sea problems and financial mechanisms to overcome it. Science and Education Issues, 1(42).

Plotnikov, I. S., Ermakhanov, Z. K., Aladin, N. V., & Micklin, P. (2016). Modern state of the Small (Northern) Aral Sea fauna. Lakes & Reservoirs: Research & Management, 21(4), pp. 315–328. Web.

Shukla, A. (2015). The shrinking of Aral Sea (a worst environmental disaster). International Journal of Innovation and Applied Studies, 11(3), pp. 633-643.