Introduction

When the drilling of the subway in the Greek capital started, nobody assumed that it would turn into a great archaeological project. Discovering the city beneath the city in Athens became a valuable source of knowledge on history and culture of the Roman Athens.

The remains of the statues, the ancient graves, pottery and other important artefacts which have been excavated during the archaeological diggings in the Athens subway became valuable contribution to the archaeological heritage of Greece and were left for the free access of public in the underground mini-museums and city museum of Cycladic art.

Though the archaeological excavations complicated the engineers’ work and extended their delays significantly, at last, the project united the engineers, the researchers and even the public. The Metropolitan Museum mini-exhibitions at the stations became a splendid opportunity for generating the sense of authentic experience among the public and involving even those who would never attend an exhibition in the traditional museum.

The remains of the statues unearthed during the construction of Athens metropolitan

The findings of the remains of the statues during the archaeological excavations in the Athens metropolitan were valuable for evaluating the new samples of archaic Greek architecture.

The remains which have been excavated during the archaeological diggings are dated to the remote time periods. The time and the conditions of their storage caused significant damage to the samples of the archaic Greek sculpture. The missing elements give rise to the archaeologists’ debates, surrounding the remains of the statues with mystery.

One of the most valuable findings of the Metro project is the marble female head which is dated to approximately 4th century AD (Image 1). Though the missing body is significant for interpretation of the meaning of the statue, the author’s intention and defining the time period of its creation more precisely, the analysis of this head can provide plenty of valuable information.

On the one hand, the facial characteristics of the depicted woman are similar to the standards for the female portraiture of the period. The rounded face, the low forehead and the eyes which seem to look into the distance have been characteristic of the most female depictions of the period. The standardization of the features of the depicted females can be explained with the Greek ideal of beauty and the fact that the actual resemblance to concrete person was not a priority for the sculptors of the period (Dillon 8).

On the other hand, the multiple ribbon which obviously protected the female’s hair is a peculiar feature which was not widely used in the sculpture and can be associated with certain individualized characteristics of the woman. For example, it is possible to hypothesize that the ribbon could belong to a huntress or an athlete (Stampolidez 180). This peculiarity can question the standardized aesthetics of the archaic female portraiture.

Another interesting finding of the archaeological excavations in Athens metropolitan was the marble acropolis dated to the 3rd century BC (Image 2). It is significant that there is no deep carving in the hair of the fragment though special should be paid to its back. The back of the statue is only roughly worked and the lines do not follow certain direction. Some researchers hypothesize that the back side was not intended for the public observation (Stampolidez 181).

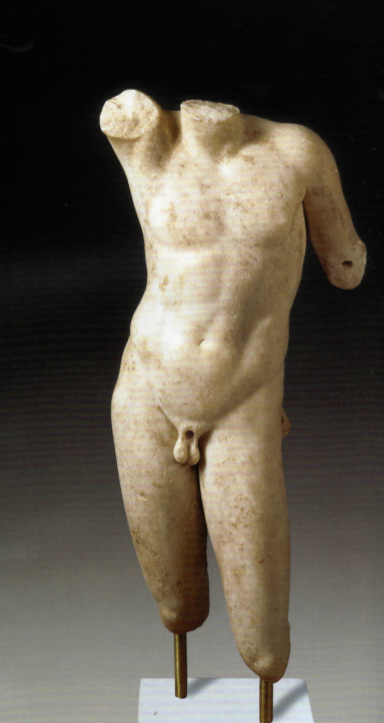

The remains of the statue of a naked youth which have been unearthed during the excavations are dated to the 1st century AD and are associated with the evolution of the aesthetics of the Kouroi sculptures (Image 3).

The Kouroi sculptures are regarded as one of the central themes in the Greek architecture, thus it is not surprising that the fragment of this statue were found among the remnants of the ancient city beneath the Greek capital. All the statues of kouros have got a number of common characteristics, such as depicting a nude youth in a frontal pose with one leg advanced and the hands hanging by the sides or clenched.

Along with all the standardized parameters which were generally used by the sculptors who created kouros, there were some peculiar features which are significant for defining the approximate period of creation of the statue, including the symbolic meaning of the statue, the character which it personifies and the purpose for creating the sculpture. Only some of these statues represent Apollo absolutely definitely, while the question concerning the character which is personified in the rest of them is rather debatable.

“Many have been discovered in cemeteries where they must have served as tombstones representing human beings” (Richter and Richter 1). It could be the case with the statue under analysis because the focus on the physiological accuracy can be associated with the evolution of the traditional statue of a Kritios boy who was usually depicted with the emphasized resemblance to the natural curves and lines of muscles of the male body.

The free interpretation of the position of hands of the youth as well as the posture can be attributed to the evolution of the aesthetics of the Kouros statues by the 1st century AD as compared to the standards of the Kouroi statues of the earlier periods.

The findings of the remains of the statues in Athens metro have become a valuable contribution to the theories of the archaic sculpture aesthetics of various periods, demonstrating the possible interpretations the Greek standards of portraiture in the 4-3 rd centuries BC as well as the evolution of the Kouroi statues standards by the 1st century AD.

The remnants of ancient graves in the Athens metropolitan

Unearthing the burial places of ancient Greeks in the Athens subway, archaeologists received plenty of valuable information concerning the burial traditions and religious beliefs of the population.

The majority of the unearthed graves were neat and rich in various utensils which the dead were supposed to need in their afterlife, including jars, amphoraes and pots. Serving as the important evidence of the Greek religious beliefs and their respect towards the dead relatives, these discovered artifacts are of great historical value because they can either support or disprove the existing historical data on the period under analysis.

Thus, along with the numerous neat grave sites which were excavated during the archaeological diggings (Image 3), in the area of Kerameikos subway station, archaeologists have discovered the skeletons of more than 150 people who have been buried in a common grave (Chelminski 1).

In contrast to the rest of the neat tombs with all their burial attributes, including the domestic utensils, coins, jewelry and even kouroi as tombstones in particular cases, these men, women and children were buried without giving them proper honors. Taking into account the strong religious beliefs of ancient Greeks, researchers made an assumption that there was a strong historical reason for violating the generally accepted burial traditions, burying people without ceremonies and paying respect to them.

These remains were dated to the period of about 430-420 BC which concurs with the time of plague upon the land as it was described by Thucydides in his History of the Peloponnesian War in which he associated the panic of the war time with the people’s carelessness concerning the laws and the burial traditions (Chelminski 2). Thus, striking the researchers with their immorality, the irregular burial sites in the area of Kerameikos subway station provide important information concerning the historical period of their creation.

The analysis of the remains of the rest of the burial sites proves that the religious beliefs of ancient Greeks were strong and the burial traditions established and respected while the violation of these principles was rather a rare exception which had to be preconditioned with strong historical reasons.

The state of the preserved skeletons of buried Greeks proves that the ancient people did not regret the costs for the materials used in tombs (Image 4). The findings of small skeletons in amphorae and storage jars prove that, on the one hand, there was special ceremony for burying little children, and, on the other hand, the rate of infant mortality in Ancient Greece was rather high, considering the number of the findings of these amphorae.

The artifacts which were excavated from the ancient tombs are interesting from the sociological perspective because they provide materials on the inequality in the ancient society and the division of the community into different strata. Though the majority of the neat burial sites contained plenty of ceremonial attributes predetermined with the religious beliefs of the Ancient Greeks, the unearthed attributes could differ in their value significantly.

Thus, the tombs of some citizens contained only cheap domestic utensils, while others were buried with coins and jewelry which they were supposed to need in their afterlife. In some examples, the care of the mourning relatives was really touching, as some of them put the flasks with the perfume and even beloved pets to the burial sites, expressing their assertion that the human life is not limited to the person’s physical existence.

The ornamentation of some of them has symbolic meaning and proves that Greeks were trying to satisfy not only practical but also spiritual needs of the dead (Image 6). The remains of the graves in the display walls of the metropolitan became the places attracting tourists and the cultural hub of Athens and the whole Greece (Rosenbaum 16).

The burial sites which have been unearthed during the archaeological excavations in the Athens subway are valuable from the historical, cultural and sociological points of view, providing evidence of observation or violation of the burial traditions by the ancient Greeks as well as the religious beliefs of the population. It is significant that most of these burial sites were left in the mini museums at the underground stations allowing the archaeologists, engineers and the public to show their respect to the remote forefathers (Randall 24).

The remains of ancient pottery excavated in the Athens underground

The variety of samples of ancient pottery which have been unearthed during the archaeological excavations in the Athens underground demonstrate not only the skills of the ancient potters but also the tendencies in the ornamentation and motives which were most widely used in it.

The analysis of the figures and lines used for the ornamentation of pots, amphorae and vases is helpful for finding the elements of the style which was used by the potter and, consequently, establishing the date of creation of the object.

Thus, some of the unearthed samples of pottery have peculiar forms and no signs of ornamentation upon them (Image 7). It is difficult to establish whether the ornamentation has not been preserved till this time or was not initially planned by the potter. The absence of ornamentation of particular samples of ancient amphorae does not diminish their archaeological value.

The analysis of the forms and materials of these amphorae helps to define possible practical use of these artifacts in the remote past. The amphorae with protuberant not flat bottom are supposed to be neck-handled and used for transportation of various liquids. Considering the fact that these amphorae could not stand erect and decorate the housing or tombs, it is possible to make an assumption that these objects were used for household practical purposes and, thus, did not require any ornamentation.

As opposed to the pottery which could have been used for domestic practical purposes, the artifacts aimed at decorating the housing or tombs were vastly decorated and their ornamentation could be rather sophisticated. The complicated ornaments would be unnecessary and absurd in domestic life though were widely used for religious purposes and burial ceremonies.

The active use of clay vessels for various purposes allowed potters to improve their skills and develop various styles of their ornamentation. The numerous amphorae, pixies, hydria and other vessels were used for the storage of domestic and precious liquids as well as for burial purposes as the urns for the ashes.

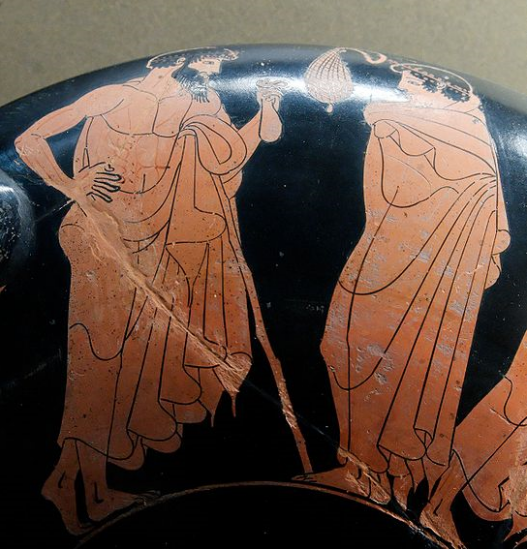

Some potters combined the religious motives with geometrical patterns for endowing their works with symbolic meaning and art value. At the same time, the objects in which the potter used the figured motifs along with the rectilinear ornament can be defined as the works of the Attic geometric style in its most developed stage (Goldstream 37). It means that particular samples of pottery which were found during the archaeological diggings in the Athens metropolitan can be dated back to the times of the Attic geometric style (Image 8).

The finding of the pottery with only geometric patterns without any figured motifs in their ornamentation can serve as the evidence of the broad time interval to which the creation of the artifacts can be dated. The pottery with the small geometric details and symmetrical rectilinear lines obviously required the developed skills of the potter and hardly were used for domestic purposes because of their value (Image 9).

At the same time, the use of the geometrical patterns only in the ornamentation of the pottery can be explained with the peculiarities of a particular pottery school even if created during the developed stage of the Attic geometric style in art. In some regions the figured motifs were not used by the potters and did not become significant for the pottery art (Goldstream 52).

The purposes and tendencies in figured art varied from region to region as well as for the various stages of the development of the pottery, for this reason, the analysis of the ornamentation of amphorae which was found in the Athens metropolitan is valuable for establishing the date of its creation and the possible use.

After the debates concerning the management of archaeological heritage, the archaeological findings of the metropolitan excavations were left for free access of the public for the purpose of providing them with the sense of authentic experience while using the city underground (Fouseki and Sandes 40).

Along with the generation of the public awareness on the issue, the justification for creating the exhibitions in the metropolitan is the preservation of the links between the findings of the excavations and the physical site where they have been discovered (Keily 33).

At present, the public can observe the samples of ancient pottery, graves, statues as well as the remains of the architecture and the municipal structure of the ancient city (Image 10) in the display walls of the Metro Railway station in Athens as well as in the city museum of Cycladic art. The Athens metro project united archaeologists, engineers and the public, and the findings of the recent excavations became the valuable contribution to the scientific knowledge on history and cultura life of Roman Athens (Stampolides 398).

Conclusion

The historical and cultural value of the artifacts which have been excavated during the archaeological diggings in the Athens subway is undeniable. The Metro project succeeded in not only building the important transportation line but also in disclosing the secrets of the remote past and contributing to the existing knowledge on history and culture of the Roman Athens.

The remains of the ancient statues, burial sites, pottery and other important findings provide information on the traditional and peculiar features of the samples of ancient civilization and can either support the existing theories concerning the life of Roman Athens or contradict them in particular moments. The findings of the Athens metro excavations have had a strong resonance in the archaeological community and provide plenty of materials for future researches.

Works Cited

Chelminski, Rudy. Unearthing Athens’ Underworld: Throughout the Decade-Long Construction of the City’s New Metro, Archaeologists Have Found a Trove of Treasures. Smithsonian magazine November 2002. Print.

Dillon, Sheila. Ancient Greek Portrait Sculpture: Contexts, Subjects, and Styles. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2006. Print.

Fouseki, Kalliopi and Caroline Sandes. “Private Preservation versus Public Presentation: The Conservation for Display of In Situ Fragmentary Archaeological Remains in London and Athens”. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 2009. Print.

Goldstream, John. “Geometric Style : Birth of the Picture”. Looking at Greek Vases. Ed. Tom Rasmussen and Nigel Spivey. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1991. 37-56. Print.

Jackie, Keily. “Taking the Site to the People: Displays of Archaeological Material in Non-Museum Locations”. Conservation and Management of Archaeological Sites February 2008. Print.

Randall, Frederika. “Eye on Athens: ’The City Beneath the City’ – Excavations for Subway Tunnels Reveal Strata of Lost Worlds; Art on the Morning Commute”. Wall Street Journal 20 July 2000. Print.

Richter, Gisela and Irma Richter. Kouroi: Archaic Greek Youths. Michigan: Phaidon. 1970. Print.

Rosenbaum, Lee. “Greece’s Underground Art”. Wall Street Journal 16 August 1996. Print.

Stampolides, Nikolaos. The City beneath the City: Antiquities from the Metropolitan Railway Excavations. Liana Parlama. 2000. Print.

Image 1

Female head dated to the 4th century BC

Image 2

Marble acrolith dated to the 3-rd century BC

Image 3

A statue of a naked youth dated to 1-st century AD

Image 4

Grave 2-nd century BC Syntagma Metro Station

Image 5

Skeleton from the 4-th century BC

Image 6

The gift arc found in a tomb

Image 7

Ancient pottery on display

Image 8

Greece Dionysius and maids of Athens amphora

Image 9

Greece amphora with geometrical pattern

Image 10

Pesistratid aqueduct 5-th century BC