In a bid to steer development and establish financial stability in the less developed countries, the developed nations through international financial institutions such as the World Bank and International Monetary Fund have always offered aid in terms of loans and grants to these nations. However, much of the aid is given in terms of long-term loans. Long-term debts to poor nations by international financial institutions meant to finance development projects are a constraint to capital formation and poverty reduction in these countries. Most of the less developed countries are highly indebted and not able to repay the loans. Most of these countries face excessive debts and the level of the debt is greatly more than their Gross Domestic Product (GDP). External Debt in these countries constitutes private, Bilateral, and Multilateral debts. These debts are a great hindrance to the attainment of their development goals as well as human development (Cheryl 1991, 84).

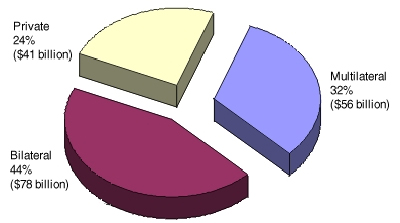

Long-term debts have slowed down the efforts and process of instituting sustainable development as well as political, social, and economical stability in these countries. These loans do not assist in financing developments. Most of the poorest nations have unsustainable debt. Most of their population lives below the poverty line and therefore they ought to use their resources in ways meant to reduce poverty and not on servicing of debt. The debt keeps on increasing to cover repayment of capital as well as interest. This debt in effect is a self-perpetuating mechanism of increasing poverty and blocking development in these countries. Most of the poorest nations have a Gross Domestic Product (GDP) below $ 785. By 1998, long-term debts in terms of private, bilateral, and multilateral by developing countries stood at $155.3 billion as shown in the diagram below.

Source: World Bank, Global development Finance 1999, Analysis and Summary Tables

Poor nations are forced to divert much of their national resources to debt servicing. Much of this goes to servicing the interest other than the principle. These countries often use between 20 and 25% of their Gross National Income on paying interest alone. Statistics show that in 1996, Africa was forced to pay $2.5 billion in servicing of its debts more than what it received in form of long-term loans. These loans are usually advanced to these countries with strings attached. Before the heavily indebted poor countries are advanced these loans, they must fulfill certain conditions set by the financiers. This is usually done through Structural Adjustment Programs (SAPs). These programs are designed to change these economies from subsistence production to international market-oriented type of production (Sachs 2000, 17).

The Structural Adjustment Program loans are usually meant to help these countries change their political, commercial, and industrial systems. This in effect is not meant to develop these nations but to enable them to be able to continue servicing their debts. These programs in effect have resulted in more harm than good to the economies of third world countries. They have resulted in widespread unemployment, rampant poverty, and wanton destruction of the environment. To solve these problems, these economies are forced to borrow more hence increasing their debts (Kuhn & Hellinger 1999, 84).

Most of the heavily indebted poor countries are unable to sustain their debts. In 1996, the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund launched an initiative to assist these countries to reduce the number of debts owing. The aim was to identify those countries with unsustainable debts and persuade their creditors to write off some of the debts to a sustainable level. To qualify for this, the poor countries were supposed to undertake sound economic policies under Structural Adjustment Programs. However, these conditions are not easy to meet. These countries were required to first show acceptance to make their citizens suffer through the provision of inadequate health care, food provisions, and education. By 1999, only five countries had qualified for these considerations in sub-Saharan Africa. The countries are Uganda, Mozambique, Guyana, Bolivia, and Mali (World Bank 1992, 114).

The initiative of the Multilateral Debt Relief was to release some national resources of a country for development purposes. This initiative has assisted these countries very little if any as these resources are far much inadequate in helping these economies realize the International Agreed Development Goals (IADGs) and Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The decision by the International financial institutions under the Heavily Indebted Poor Countries was by itself punitive. Most countries could not afford a debt-to-export ratio of over 200 to 250%. This restriction threw most poor economies out of the program (George 1990, 69).

These conditions assume efforts to reduce poverty. They force these governments to adopt the privatization process as a strategy to raise revenue. This is always a ploy by the developed countries to change capital ownership structures to favor foreign multinational companies, a condition that lowers the living standards of their people to mere survival. The International Financial Institutions are controlled by the developed countries to their interests. Their policies are made to ensure that poor nations remain highly indebted and on structural adjustment programs. This is the reason why these institutions provide insufficient debt relief to the heavily indebted poor countries so that they have to spend more on debt repayment at an expense of poverty reduction programs (Serieux & Samy 2000, 527-548).

In conclusion, debt cancellation to sustainable levels remains the only possible solution to the problems of the heavily indebted poor countries’ long-term debts crisis and increased aids in terms of grants and adequate debt relief for middle-income economies with an unsustainable amount of debt. Efforts need to be made to provide greater market access for their products. Consequently, trade restrictions should be lessened and fair prices offered to their products. Aids and grants provided to these countries should be in form of capital goods to accelerate the rate of industrial growth in these economies. Structural changes of their economies from agriculture to manufacturing economy are required if they have to favorably compete with products from developed countries in the international markets. This is the only way these countries can sustain themselves without debts. Without the debt burdens, developing countries would be able to channel their national income to projects aimed at the capital formation and poverty reduction (Serieux & Samy 2000, 123-125).

Reference List

Cheryl, Payer. Lent and Lost 1991. Foreign Credit and Third World Development. New Jersey: Atlantic Highlands.

Hansen-Kuhn, Karen, and Hellinger, Doug. 1999. Conditioning Debt Relief on Adjustment: Creating the Conditions for More Indebtedness.

Sachs, Jeffrey. 2000. The Charade of Debt Sustainability, Financial Times, p. 17.

Carrasco and McClellan, 2007, “Foreign Debt: Forgiveness and Repudiation” University of Iowa Center for International Finance and Development E-Book.

George, Susan. 1990, A Fate Worse Than Debt: The World Financial Crisis and the Poor. New York: Grove Weidenfeld.

Serieux, John and Yiagadeesen Samy. 2000, The Debt Service Burden & Growth: Evidence from Low-Income Countries, Paper presented at the United Nations University.

Serieux, John. 2001, The Enhanced HIPC Initiative and Poor Countries: Prospects for a Permanent Exit, Canadian Journal of Development Studies, 22 (2): 527-548.

World Bank. 1992. Effective Implementation: Key to Development Impact, Report of the World Bank’s Portfolio Management Task Force (Washington).