Abstract

This paper aims to explore the rich cultures of Arab and Americans and their differences in terms of literature. The main focuses of this study are the Arab novelists who traveled to the USA and produced novels, their experiences, the obstacles and hindrances they encounter with the newly introduced culture and various facts and opinions about the status of the Arabs in the USA, how they survived and how their writings become popular in the western world.

Facts provided us the evidence that Arab writings and novels are seldom read or even noticed in America until the boom of September 11, 2001, popularly known as 9/11.

Abdul-Nabi Isstaif

Recent writing of Abdul-Nabi Isstaif, professor of comparative literature at the University of Damascus, addressed the impact of the September 11 attacks on Arab culture during his April 18, 2006 lecture titled, “9/11 and Its Impact on Contemporary Arab Culture.” He was a visiting scholar on a Fulbright teaching fellowship at Roger Williams University last year. He pointed out that it is “high time that the Arab and Western worlds contact each other and talk to each other first-hand” instead of perpetuating stereotypes and misinformation. He noted that the current state of affairs for the Arab people is “miserable” but that “Arab culture nowadays is quite strong,” which will ultimately contribute to greater pan-Arab solidarity and an exchange of ideas (Eckert & Colla, 2006).

West countries often perceive Arab culture as a single entity and this belief encompasses Arab’s 22 states involved in border disputes, power-plays, and religious clashes. Contrary to several Western ideas of great oil wealth throughout the Middle East, the region is very “weak, divided, and poor.” Isstaif argued that most Arabs seem to be living in the nineteenth century and are increasingly seeking to return to their “glorious past.” The only thing “up-to-date” in the Middle East are its security devices and security forces.

Before September 11, the questioning of Arab unity and culture occurred as a result of Saddam Hussein’s invasion of Kuwait, Isstaif noted. This act abrogated traditional notions of Arab solidarity, forcing Arabs to ask the question, “Who are we?” This questioning continued through the 1990s, rising to a crisis pitch in September of 2001. This “act of revenge…[possessing] no ideological dimension and no religious dimension” forced the Arab people to assess their attitude towards the “other” both within the Arab world and outside. Arabs became increasingly cognizant of the position and well-being of minorities—Kurds, youth, women—and engaged in a more frank dialogue of their status in the dominant Muslim-Arab society. The region’s population also enjoyed a heightened awareness of cultures and happenings outside its borders, particularly in the West. Isstaif perceived Arab culture as being “involved in this defensive mode” because of the strong anti-Arab backlash. “We don’t have anything that will alienate the other. We’re not against the West, we’re not against modernity,” he noted.

The Arab world continues to struggle with accurate perceptions of the West as well as methods for internal renewal and reform. Formerly, the United States was viewed as the land of freedom; today, it’s the “land that hunts Muslims.” Many Arabs perceive American culture as a direct extension of White House foreign policy, a reality that does not depict Americans favorably abroad. The Arab world is also contending with questions about the future. Should we defend tradition at all costs or be critical? Should we take reform as being important? Do we take the U.S. model? Do we democratize from the outside, or from within? Isstaif noted that, yes, “we’d like to do it (adopt democratic rule), but we’d like to do it ourselves, from the inside. We don’t want help from the outside, specifically from the United States.”

Cultural Differences

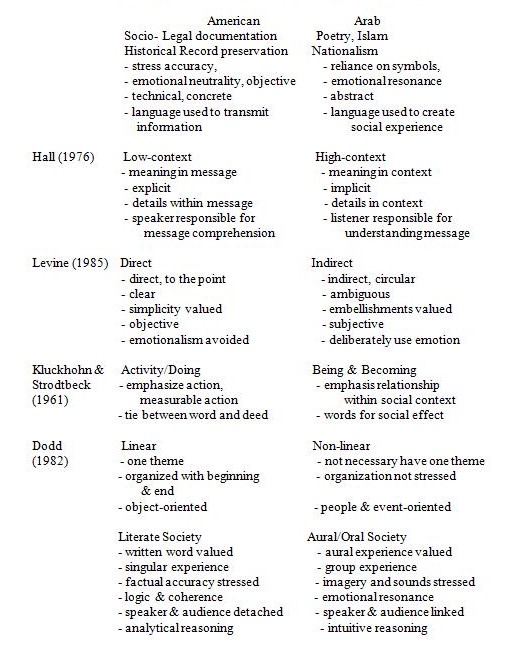

According to Zaharna, “The Arab and the American culture have two distinct perspectives for viewing language and, as a result, two differing preferences for structuring persuasive and appealing messages. Several frameworks for viewing cultural variations were used to develop a chart on “cultural communication preference” for Americans and Arabs. For the Arab culture, emphasis is on form over function, affect over the accuracy, and image over meaning. An awareness of these cultural differences can help facilitate client relations, media training, and message appeals”.

Zaharna infers that it is the culture of Americans to use language as a medium of communication and to convey information. Emphasis is on function and by extension substance, meaning, and accuracy. A message may tend to be valued more for its content than style. For the Arab culture, language appears to be a social tool used in the weaving of society. Emphasis is on form over function, affect over the accuracy, and image over meaning. Accordingly, content may be less important than the social chemistry a message creates.

Below is a chart on “cultural communication preference” for Americans and Arabs created by Zaharna.

Cultural Variations of Messages In American and Arabic Communication Preferences

References

- Eckert, S. E., & Colla, E. (2006). 9/11 and its impact on Contemporary Arab Culture. [Seminar with Abdul-Nabi Isstaif, Professor of Comparative Literature, University of Damascus]. Middle East and Islamic Studies Seminar Series. Web.

- Zaharna, R. S. (2001). Bridging Cultural Differences: American Public Relations Practices & Arab Communication Patterns*. Washington DC. Web.