Executive Summary

The geographical location of Dubai has given this city the advantage of becoming an international logistics hub. Dubai’s increasing logistical capabilities provide opportunities both to the UAE and the Arabian Peninsula at large. The government of Dubai is currently funding the construction of an aerotropolis dubbed the DWC that will become the largest airport in the world.

When compared to other GCC countries, it is noted that Dubai has one of the most efficient logistics infrastructure. However, in attempts to become an international logistics hub, the city is faced with organisational and institutional challenges that should be fully addressed.

Introduction

It is noted that the process of trade internalisation is propelled by 2 main engines. These are logistics and telecommunication. Technological advancements in information and communication have attracted a great deal of attention because of the manner in which they have transformed the day to day operations of individuals and institutions in the sector. This fact is evidenced by the influence of satellite TV, the internet and the cellular phone among other technological devices (Abdel-Maksoud & Mustapha 2009).

Logistics as a driver for trade internalisation has been equally momentous. Because of the ever increasing desire to integrate, connect and standardise procedures and handling of operations in the transport sector, economies all over the world have access to synergies that were unthinkable 30 years ago (Air Cargo World 2010a).

The transformation brought about by this can only be compared with what happened at the end of the 19th century. This is when steamships, railroads and the telegraph completely changed the face of international financial relations and trade. The innovations that took place at the close of the 20th century and which have persisted into the 21st century have taken global interactions to another level. They have totally transformed economic geography in the world today (Air Cargo World 2009).

Dubai has emerged as a significant location in the resulting transmutation and within a relatively short time, it has grown to match the standards of some of the most established trading and logistics hubs of the world. This is locations such as Singapore and Germany as already mentioned in the paper.

Dubai has some of the most efficient and active ports in the world, courtesy of its mid- way location between Europe and Asia. Another major advantage of Dubai as a logistics hub in the world is the fact that it is also strategically located at the centre of the most important shipping routes that link the Indian, Atlantic and Pacific oceans (Backman 2008).

In this paper, the author will outline the Dubai’s potential to become one of the leading logistics hubs in the world. The report will address the logistics cluster as far as the city is concerned, provide a critical analysis of the new Aetropolis as well as compare Dubai and Singapore from an international perspective.

Other issues that will be addressed in the report include the transport and communication infrastructure in the country, a critical analysis of global competitors in the industry, the role of public institutions as well as the macroeconomic environment. The report will also provide recommendations on how to make the city a logistics hub in the world in the near future.

Literature Review

The Logistics Cluster

Analysts are of the view that logistics systems span over three dimensions. These include spatial, vertical and time dimensions (Air Cargo World 2010b). Logistics chain partners are very dynamic and as such, they change their operations to respond to new cost conditions and infrastructure in the industry. As the traffic changes in growth and pattern, logistics and infrastructure development are affected with respect to route development, handling, transhipment and service frequency (DiBenedetto 2011).

From the late 1970s, Dubai has emerged as an important pillar of trade development in the Arabian Peninsula (Bruns 2009). As Dubai emerges as the leading logistics hub in the region, it has positively impacted not only on the economy of the Emirates but also that of the entire region.

Over the last 10 years, port facilities in Kuwait, Qatar, and Saudi Arabia have been overwhelmed by the surge in trade volumes that resulted from the rapid increase in the region’s economic activity. In this regard, Dubai fills the vacuum that would have otherwise crippled the development of economies in the Peninsula region (Datamonitor 2011).

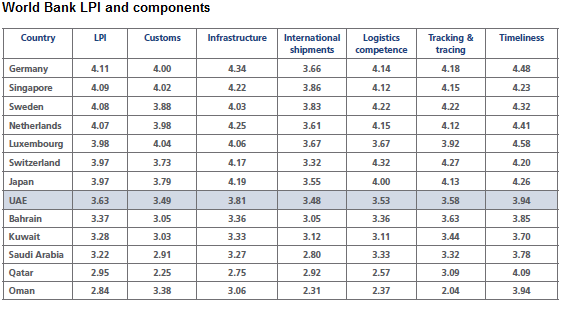

When analysing Dubai’s GDP, contributions realised from logistics falls under the subsector of Communication and Transportation storage. In 2010, the sector contributed 9.8% to the country’s GDP. In the same year, the supply chain and logistics industry in the United Arab Emirates had a 3.63% growth rate (Airguide Business 2012). The figure below shows that the UAE was the only country in the Middle East that featured in Logistic Performance Index (LPI) of the World Bank in 2010 (World Bank 2011):

Figure I

Source: World Bank 2011

The performance of Dubai as a logistics hub will definitely improve given that in 2011, the expenditure in the Transport and Roads Authority in Dubai was estimated at AED 10.84 billion. AED 2.9 billion was part of the operational budget while AED 7.91 billion formed part of capital and project budget. The 2011 expenses were at least 30% of the total expenditure of the government of Dubai which was approximately AED 35 billion (Gilani & Gilani 2012).

The main competitive advantage that puts Dubai in the forefront is the fact that it has an effective combination of the different modes of transport that connects all countries in the region. It is expected that in the next few years, infrastructure in Dubai will be complemented by the railroad network of the GCC (Ford 2010).

The effective physical and geographical connectivity of the city is enhanced by a cluster of logistics corporations in the Free Zone that brings critical mass, international projection and know-how. The main focus to this end is on the maritime and air modes of transport together with rail and road (Meixell & Kenyon 2010).

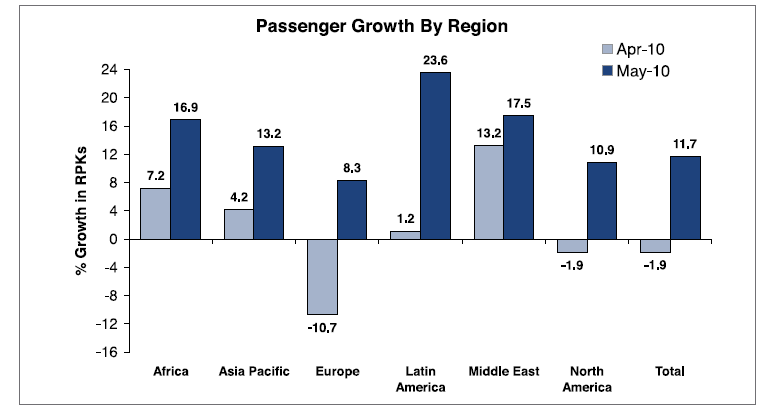

In 2009, Airports Council International released statistics which indicated that 23 out of the 30 busiest airports in the world had recorded a negative growth. The other airports- apart from Dubai International Airport- that reported an increase in business growth included Jakarta (13%), Bangkok (4%) and Beijing (13%). The implication is that Dubai International Airport is slowly but surely becoming one of the fastest growing airports in the world (Thomasr 2011). The figure below vividly illustrates this position:

Figure II

Source: Thomasr 2011

In 2009, Dubai’s cargo volume grew by 6%. It is worth noting that during the last quarter, the volume had recorded double digits growth, reaching a high of 27% in December. The total cargo volume for the entire year was 1,936,481 tonnes as compared to that of 2008 which was 1,859,428 (Coia 2012).

Dubai is the 3rd largest re-export hub in the world, coming behind Singapore and Hong Kong (Meixell & Kenyon 2010). In 2010, the Dubai government- in collaboration with other regional partners- made efforts to form a logistics platform dubbed the Dubai Logistics Corridor. This will be the first facility in the Middle East that has the potential to link air, land and sea. After the construction of the Emirates railway, the corridor will be fully integrated and connected to the transport system of the UAE (Pollard 2011).

The development of logistics in Dubai is wrought with challenges that can be divided into two major categories. These are organisational and institutional challenges. Organisational factors are those related to the handling and shipment processes while institutional factors are those related to public services that are linked to trade (Plunkett 2010). The management of containers in Dubai (like in most emerging markets) has been hampered by inefficiencies.

In the West- mainly in Europe and the United States- a business person is able to receive their container in time and load it onto a truck or train from the ship en-route to diverse destinations. This is either within or outside the borders of the country. The entire process is seamless and requires simple documentation.

In transition economies like those in the Middle East, transporting goods between countries can prove to be a very hectic exercise with regard to custom requirements. The facilities in Dubai serve various nations but inefficiencies are brought about by poor access to surrounding countries. Such inefficiencies are beyond the capability of UAE authorities (Saidi 2011).

The New Aerotropolis

Airports in urban centres are evolving from city airports to become airport cities. The resulting “aerotropolis” will become critical determinants of economic development in the near future. This evolution has positioned airports at the centre of economic integration, economic growth in urban areas and in the making of decisions for business location (Turney 2006).

The Dubai World Central (DWC) has undergone such evolution to become a quintessential aerotropolis. In the contemporary world, global corporations such as Benetton, Dell, Microsoft and Nike are not only managing their brands through the use of logistic networks, but they are also moving their products and services all over the world. To this end, aerotropolis will be a force to reckon with in the economic world.

Historians in this field are of the view that the concept of aerotropolis was developed by John Kasarda. This man was an Entrepreneurship and Strategy Professor who conducted research and documented his findings in various books and articles. He found that airports are undergoing a transformation from mere supply chain and transportation channels to multi- faceted commercial centres (Plunkett 2010).

The airports are evolving to address the needs of business persons and consumers through the provision of conventions, exhibitions, meetings, office, retail, entertainment, and hospitality services. These new models of international airports attract businesses mainly in the high- value added and sensitive sectors such as perishables, medical instruments, aerospace equipment, pharmaceuticals, and microelectronics (Gilani & Gilani 2012).

Such airports are located close to logistics centres because predictability, speed, and connectivity are of fundamental importance to this sector. The government of Dubai has made an investment of 33 billion USD in developing the infrastructure of the DWC. The DWC cargo section at Al Maktoum International Airport opened its doors in June 2010.

This is just the first phase of a project that is intended to transform the airport to one of the largest in the world. This is for both cargo and passengers. The aim is to make it the largest airport in the world by 2020 (DiBenedetto 2011).

The DWC will have 0.4 million M2 offices, 1 million M2 warehouses, and 24 million M2 for building 10 thousand residential units. On completion, the facility will host close to a million residents and 0.7 million workers (Airguide Business 2012). The project reflects the commitment of the government in Dubai to transform the city into a logistics and trading hub in the region through the development and implementation of similar systems and infrastructure.

The main objective of coming up with a 33 million USD project is to make sure that goods are transitioned seamlessly between land, air and sea. The platform will become a logistics hub that will meet the needs of the entire region and adequately address the increasing inter-connectedness and international linkages.

The DWC will be the first aerotropolis in the world to have a sea- air corridor (Ott 2011). This will make it possible for containers off- loaded at the ports to be airlifted to their destinations in less than three hours. It will provide Dubai with a state of the art custom clearing and administrative capability.

On completion, it will have the capacity to hold 13 million tonnes of cargo at a go. This will be at least three times the capacity of Memphis Airport, which is currently the largest cargo airport in the world. The facility will have a capacity of between 120 and 150 million passengers every year.

This will dwarf the capacity of Hartsfield- Jackson International Airport in Atlanta. By 2008, the latter had a maximum capacity of 90 million passengers and was ranked as one of the busiest airports in the world. The DWC will be complemented by an aviation network of 140 KM2 (Thomasr 2012).

A Comparison between Dubai and Singapore Business Hubs from an International Perspective

The World Bank LPI ranked the UAE at 24th place in the 2010’s study, making it the best in the Middle East. Germany was ranked first while Singapore was second. According to figure 1 above, the UAE leads the other GCC countries in four dimensions. It only loses out to Bahrain in tracking and tracing of cargo and to Qatar in the timeliness dimension. It is not surprising that the other countries in the region do not match the logistics infrastructure of Dubai (World Bank 2011).

In another report that documented the Global Competitive Index (herein referred to as GCI), the World Bank ranked the UAE as number 23 with 4.92 points as compared to 5.60 points that were awarded to Switzerland which was ranked first. Again, the UAE had the most competitive infrastructure in the Gulf region (Riley 2012).

It is however important to note that although infrastructure is essential for economic competitiveness, complementary policies such as transport regulations and trade liberalization are equally important. This is the reason why Qatar performed better than UAE in overall in spite of the fact that the UAE had better infrastructure (World Bank 2012).

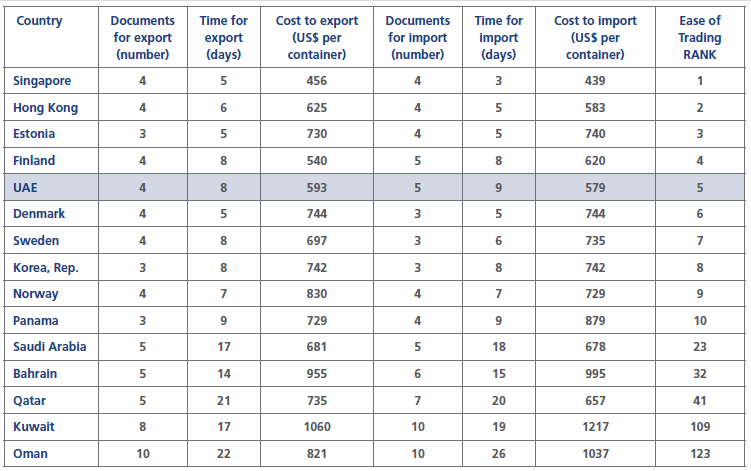

A third report by the World Bank entitled “Doing Business” pointed out that the UAE was among the best ten reformers in the world. In 2008, the UAE was ranked 47 but in 2009, it was ranked 33. One of the main reasons for this improvement is the fact that the cost of starting business in the country had reduced significantly during this period. In the “trading across borders” section of the report, UAE recorded a very impressive performance.

To this end, the country improved from number 13 in 2008 to position 5 in 2009. The best explanation for the improvement was that the time and documentation that was required for export had highly reduced in the period under review. Moreover, cost of export and import by container in the UAE also went down in 2009 (World Bank 2012). This is clearly illustrated in figure 3 below:

Figure III

Doing Business across Borders in Dubai

Source: World Bank 2012

In order to determine how far Dubai is from becoming the world’s largest and most advanced logistics hub, it is necessary to compare it with Singapore which is currently the world’s number two (Official Airline Guide 2012). In 2009, the GDP of Singapore was 2.9 times that of Dubai.

The disparity is reflective of the differences between the two cities with respect to their economic standing. The economy of Dubai is envisaged to grow by about 11% each year. At this rate, the economy will have hit the 108 billion USD mark by the end of 2015 (UAE Defence and Security Report 2010). By 2015, the population of the city will have grown to 2.5 million people. Unlike in the case of Singapore, Dubai has enough room for expansion because its land area is 7 times larger than that of Singapore (Thomasr 2010c).

UAE has a very high inflation rate which stands at 6.7%. This is as compared to that of Singapore which stands at 1.1%. The main reason for the high inflation rate is the fact that the prices of rent in the city have been increasing in the past ten years. This increases the operation costs for companies operating in Dubai. As a result, the government of Dubai should find ways of reducing rent in order to attract more foreign direct investment in the future (McCue 2012).

Singapore’s scale of sea freight operations is larger than that of the UAE, leave alone that of Dubai. However, the Dubai government is rapidly expanding the Jebel Ali Port to make sure that in the next ten years, it will be able to hold three times its current capacity of 5 million TEUs (Field 2010). As already mentioned and indicated in figure I, Singapore’s LPI rating is far much higher than that of the UAE. However, the cost of domestic logistics in the two countries is comparable (Middle East Economic Digest [MEED] 2011).

Method and Data Analysis

Overview

In this section of the paper, the author will present information that was collected from managers in leading international companies. The information touches on the current position of Dubai as a global logistics hub and what is needed to take the city to the next level on the logistics scale.

The research was conducted in 2009 by Cedwyn Fernandes and Gwendolyn Rodrigues, documented in an article titled “Dubai’s Potential as an Integrated Logistics Hub” and published in the 3rd issue of the 25th volume of the Journal of Applied Business Research.

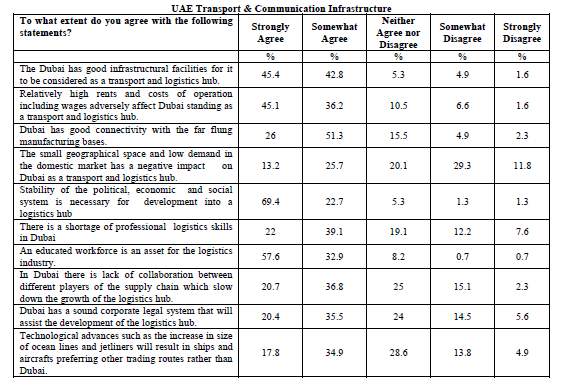

Transport and Communication Infrastructure

According to the table presented in Appendix I, 90% of the managers who were interviewed either strongly agreed or agreed that the infrastructure of the city was adequate to support the endeavours of Dubai to become a logistics and transport hub in the region and in the world. 80% of the managers were in agreement that the city’s capacity as an international logistics hub has been hampered by the increase in rent. 58% of the informants pointed out that there was lack of adequate collaboration between supply chain participants.

52% of them either agreed or strongly agreed that the advances made in the airline and shipping industry may have a positive effect on logistics. 59% of all managers that were surveyed agreed that the domestic market in Dubai was small and was having a negative effect on Dubai’s logistics (Fernandes & Gwendolyn 2009).

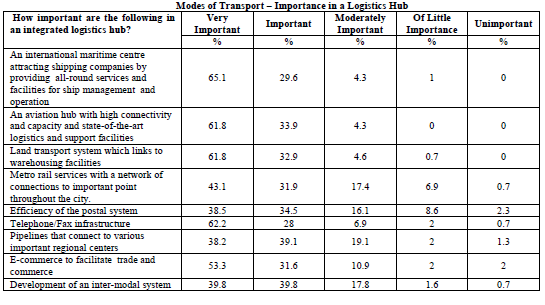

Mode of Transport

A strong maritime system is very important for any city that desires to become a logistics hub. To this end, the respondents outlined how important the different modes of transport were.

They rated the various modes of transport from Unimportant to Very Important. 95% of the informants pointed out that the development of a seamless linkage between land, sea and air transport was either very important or important in making Dubai the world’s largest logistics hub. The findings on this part are tabulated in Appendix II (Fernandes & Gwendolyn 2009).

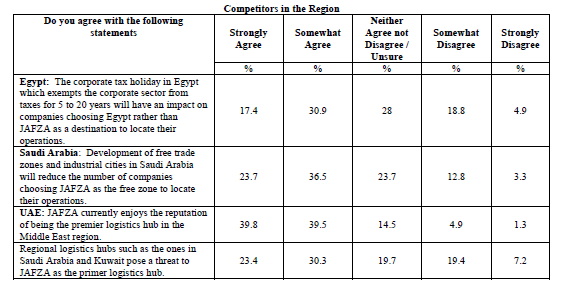

Competitors

Other neighbouring nations such as Qatar are also heavily investing in logistics infrastructure. The managers outlined their perceptions on the threat posed by other nations. The results are in Appendix III of this report (Fernandes & Gwendolyn 2009).

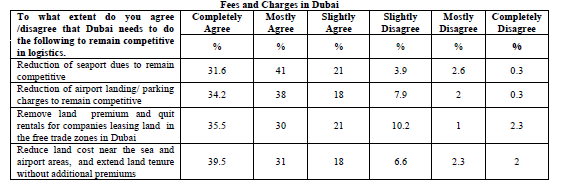

Fees

In this section of the report, the author addressed the fees charged or incurred by traders when using Dubai ports to transport their goods. The informants were required to indicate the degree to which they felt that government fees and regulations were affecting the prospects of Dubai becoming the largest logistics hub both in the region and in the whole world.

71% of the managers either strongly agreed or agreed that the government should reduce airport and seaport landing charges in order to increase the competitiveness of Dubai. They also pointed out that it was important to reduce land costs. More findings are tabulated in Appendix IV of the report (Fernandes & Gwendolyn 2009).

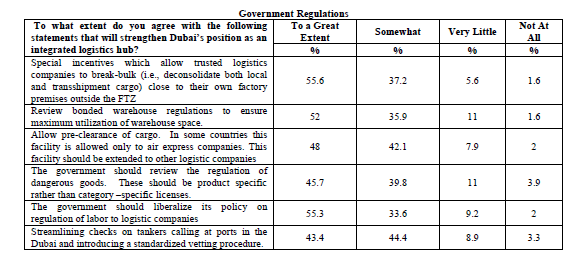

Government Regulations

These are regulations that apply to the logistic operations of companies. The managers were required to point out the extent to which the inflow of companies would increase should the government change the various regulations. The findings are tabulated in Appendix V of the report (Fernandes & Gwendolyn 2009).

Role of Public Institutions

Many countries have improved their logistics after transforming their public institutions. The informants were required to use a scale in rating the various institutions that were contributing to the process of turning Dubai into a logistics hub. The findings are documented in Appendix VI of the report (Fernandes & Gwendolyn 2009).

Recommendations

Dubai’s transport and communication infrastructure is better than that of most GCC countries. With the development of the DWC and proposed expansion of the Jebel Ali Port, the facilities of the city will be adequate to support the vision of becoming the world’s logistics hub.

The main concern for the city is retaining cost advantages because of the inflation rate. This is as a result of the increase in cost of labour that can be traced to increased rents (Thomasr 2010a). For the city to attract business from more logistics players, the authorities should address the rates charged in the Free Zone. The land allotment rates should be structured to encourage companies to relocate more operations and businesses to Dubai.

Players in the industry should understand the importance of collaboration between supply chain participants. Close to 93% of all consumer products in Dubai are imported. As a result of this, substantial transport costs and other expenses are incurred (O’Connell 2012). Studies should be conducted to identify how collaboration fosters improved supply chain responsiveness and efficiency.

Companies from the GCC region can freely trade and reach out to a market of close to 40 million people. Many of the goods that enter and leave GCC countries pass through Dubai. In order to maximize the benefits presented by the GCC union, Dubai policy makers should pursue the implementation of the proposed Monetary Union.

Much emphasis should also be put on eliminating trade barriers. Some of such trade barriers are quite hidden but they have dire ramifications all the same. Some of the barriers include constant delays at GCC borders that highly hamper the flow of services and goods (Smith 2010)

The managers who were interviewed pointed out that there is lack of professionals with cutting edge skills in logistics. Universities in Dubai have started offering courses in supply chain management and logistics to address this problem. Moreover, there is need for professional bodies to set up chapters in Dubai in order to enhance the level of training.

When compared to countries such as Germany and Singapore, the UAE has a long way to go as far as the implementation of e-commerce is concerned. The disparity between the two countries is mainly brought about by the absence of gateways for e-payments. The financial institutions in the country should come up with proper gateways of payments in order to facilitate safe and timely e-payments (O’Connell 2012).

Dubai’s custom authorities should work hand in hand with logistics companies by handing over the responsibility of cargo facility pre-clearance to these companies. Lastly, the government should put in place measures to make sure that public institutions are providing the right environment for efficient trade in logistics. Some of these include setting up of more judicial courts to reduce the time taken to settle business disputes as well as to protect property rights (Thomasr 2010b).

Conclusion

Dubai is strategically located and as such, in a better position to become a leading logistics hub in the world. However, there are various administrative, organisational and logistical issues that have to be addressed before the success of such an endeavour is realised. The most important thing is that the government of Dubai is committed to make sure that the objective is achieved.

Because the infrastructure that is needed is either in place or in the process of being put in place, the attention of the government should shift to the provision of highly trained human resource and eliminate bureaucratic trade barriers associated with emerging economies.

References

Abdel-Maksoud, J & Mustapha, K 2009, “Relationships amongst value creating variables in an international freight forwarding and logistics firm: testing for causality”, Journal of Applied Management Accounting Research, vol. 7 no. 1, pp. 63-77.

Air Cargo World 2009, ‘Dubai logistics has Asia, CIS focus’, MEED, vol. 99 no. 6, p. 12.

Air Cargo World 2010a, ‘It’s cargo for openers at airport of the future, MEED, vol.100 no. 4, p. 9.

Air Cargo World 2010b, ‘Dubai moves ahead of the pack’, MEED, vol. 45 no. 23, p. 23.

Airguide Business 2012, ‘Business & industry news – airline finance news’, Applied Management, vol. 2 no. 2, pp. 1-33.

Backman, M 2008, Asia future shock: business crisis and opportunity in the coming years, Palgrave Macmillan, London.

Bruns, A 2009, ‘Open the gates’, Site Selection, vol. 54 no. 1, pp. 28-33.

Coia, A 2012, ‘Ship to the desert’, Automotive Logistics, vol. 1, pp. 44-46.

Datamonitor 2011, ‘United Arab Emirates 2011’, UAE Country Profile, vol. 4, pp. 1-65.

DiBenedetto, B 2011, ‘Looking to the future’, Journal of Commerce, vol. 9 no. 16, pp. 18-20.

Fernandes, C & Gwendolyn, R 2009, “Dubai’s potential as an integrated logistics hub”, The Journal of Applied Business Research, vol.25 no. 3, pp. 123-134.

Field, AM 2010, ‘Middle East’s growth corridor’, Journal of Commerce, vol. 11 no. 45, pp. 40-43.

Ford, N 2010, ‘Pulling Middle Eastern logistics together’, Middle East, vol. 414, pp. 54-57.

Gilani, S & Gilani, B 2012, ‘Selling the desert: entering the Korean market to promote Dubai as a tourist and commercial destination: a DTCM approach’, International Journal of Business Research, vol. 7 no. 3, pp. 63-79.

McCue, D 2012, ‘Changing global trade lanes’, World Trade: WT100, vol. 25 no. 6, pp. 30-33.

Meixell, M & Kenyon, G 2010, ‘The effect of logistics outsourcing on plant delivery performance: an empirical study of the US automotive supply chain’, MEED, vol. 2 no. 2, pp. 648-659.

Middle East Economic Digest 2011, ‘Doing business in Dubai’, MEED, vol. 1, pp. 54-64.

O’Connell, JF 2012, ‘The changing dynamics of the Arab Gulf based airlines and an investigation into the strategies that are making Emirates into a global player’, World Review of Intermodal Transportation Research, vol. 1, pp. 94-114.

Official Airline Guide 2012, ‘Dubai’, MEED, vol. 2 no. 3, pp. 2-5.

Ott, J 2011, ‘Future cargo hubs’, Aviation Week & Space Technology, vol. 161 no. 19, pp. 66-70.

Plunkett, JW 2010, Next boom: what you absolutely, positively have to know about the world between now and 2025, BizExecs Press, New York.

Pollard, J 2011, ‘Islamic banking and finance: postcolonial political economy and the decentering of economic geography’, Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, vol. 32 no. 3, pp. 313-330.

Riley, J 2012, ‘Logistics hubs: the future of distribution’, South Carolina Business, vol. 29 no. 3, p. 16.

Saidi, N 2011, ‘Dubai returns to business as usual’, Middle East, vol. 422, pp. 50-52.

Smith, B 2010, ‘Scared by, of, in, and for Dubai’, Social & Cultural Geography, vol. 11 no. 3, pp. 263-283.

Thomasr, K 2010a, ‘Crucial test for new airport’, MEED: Middle East Economic Digest, vol. 54 no. 24, pp. 40-41.

Thomasr, K 2010b, ‘New era of logistics growth’, MEED: Middle East Economic Digest, vol. 54 no. 48, pp. 13-14.

Thomasr, K 2010c, ‘Danzas AEI Emirates’, MEED: Middle East Economic Digest, vol. 54 no. 40, pp. 26-27.

Thomasr, K 2011, ‘Dubai’s silver-service hub’, MEED: Middle East Economic Digest, vol. 56 no. 48, pp. 3-4.

Thomasr, K 2012, ‘Centre of trade moves south’, MEED: Middle East Economic Digest, vol. 58 no. 48, pp. 70-77.

Turney, R 2006, ‘Dubai vies to become logistics gateway’, Shipping Digest, vol. 83 no. 4324, pp. 92-94.

UAE Defence & Security Report 2010, ‘Forecast scenario’, Air Cargo World, vol. 1 no. 1, pp. 64-68.

World Bank 2011, World development report 2010: reshaping economic geography, World Bank, Washington DC.

World Bank 2012, World development report 2009: doing business across borders, World Bank, Washington DC.

Appendices

Appendix I: Transport and Communication Infrastructure

Appendix II: Modes of Transport

Appendix III: Competitors

Appendix IV: Fees

Appendix V: Government Regulations