Introduction

The knee is the foremost complex and critical joint within the human body. It comprises the saddle joint and two condylar joints. The condylar synovial joint is comprised of the tibiofemoral and femora patellar joints. The menisci, which shape a divider within the empty of the knee, make it as troublesome as the bear. Cartilage, bones, ligaments, and tendons are the four primary components of a knee.

Overall, three bones come together to create the knee joint. Namely, the patella serves as a shield before the thighbone. The meniscus is thick and strong, acting as a stun safeguard and contributing to joint soundness in differentiation to the articular cartilage. Tears within the knee cartilage are, in some cases, misdiagnosed as meniscus wounds. This paper explores the knee’s systems and work and examines the medications, perils, and health variables that influence the knee.

Kinesiology of the Knee Joint

In differentiation to the hip, the knee’s complexity is characterized by the pronunciation between the tibia and femur, which is more removed within the knee. The knee’s polycentric movement allows it to roll and slide; the movements are predominantly supportive (Angin & Simsek, 2020). Indeed, the developments of the hip and lower leg are inseparably connected to the movement of the knee joint.

Thus, the knee is exposed to frequent trauma because it always underpins the body’s two longest bones, putting it within the line of critical strengths and minutes (the femur and the tibia). The tendons, stiff consistency, meniscus, capsular tendons, and capsules all contribute to inactive soundness, though strong powers contribute to energetic harmony. The collective energy between detached and dynamic adjustment grants complex knee movements.

Although the verbalization surfaces of the tibia and femur ought to be closely adjusted, they are not. In this manner, the knee’s inactive soundness is decided more by the limitations on the delicate tissues encompassing the joint than by the solidarity of the bones (Lippert & Minor, 2017). The tibiofemoral and patellofemoral joints are the two that comprise the knee joint, and they take the brunt of the push that individuals put on them day by day and during sporting activities. The complex joint permits liquid movement, transmits powers from the thighbone to the shinbone, assimilates and redistributes stresses caused by movement, and shields the leg bones.

Biomechanics of the Knee Joint

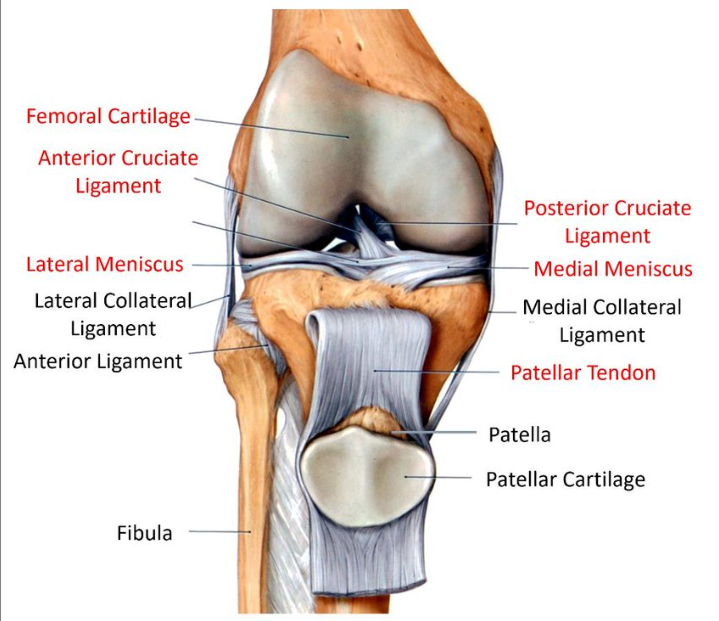

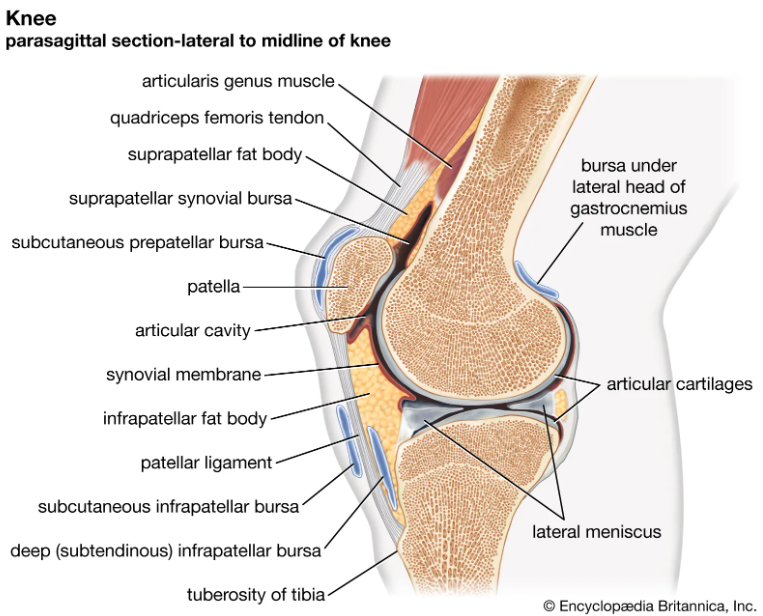

As demonstrated in Figure 1, the knee is characterized by a complex structure. The hard bulge before each knee is called the kneecap (Stetter et al., 2019). The title for this projecting piece of bone is the patella, present in Figure 1, being held by the patella tendon. Synovial joints within the knee are vastly predominant. Synovial joints comprise greasing-up synovial liquid inside a tendon capsule, as shown in Figure 2, around the synovial membrane and lateral meniscus regions.

The tibia and femur shape a joint at their midpoint, known as the knee, engulfed by the infrapatellar fat body in Figure 2 below. The femur closes in two condyles, adjusted handles (Abid et al., 2019). The tibia locks a groove that obliges these condyles, portrayed by its shape. The side of the shinbone that faces absent from the other knee is called the sidelong tibial level.

The knee joint is a complex hinge joint that consists of three bones: the femur, tibia, and patella. It is responsible for the flexion and extension of the leg and provides stability to the lower extremity. The knee joint is subjected to mechanical loads from walking, running, and jumping. During movement, the knee joint is subjected to compressive, shear, and torsional forces.

Varus and valgus misalignment occur when the knee bends too far in (varus) or too far out (valgus) of its normal range of motion (Stetter et al., 2019). This misalignment can lead to increased stress on the joint and can lead to pain and injury. The Q-angle measures the angle between the quadriceps muscle and the patellar tendon (Abid et al., 2019). It is used to assess knee alignment and determine if there is an increased risk of injury.

The side of the tibia positioned closer to the other knee is called the average tibial level; the tibia is connected with a small side joint. Articular cartilage and articular cavity act as a pad between the closes of bones in a joint, as evident in Figure 2. Cartilage within the joints is lubricious and smooth, permitting simple development that does not wear on the joints (Angin & Simsek, 2020). White and rubbery with a sticky feel, cartilage is simple to spot. Cartilage is thick and challenging to masticate. As a smooth surface for joints to slide over, articular cartilage acts as a shock absorber with the support of the lateral meniscus. The closes of the femur and tibia, the tibia’s surface, and the patella’s raise all incorporate articular cartilage, which serves as a stun safeguard (patella). Thus, the complexity of the knee’s structure and the significant loads of pressure on bones and joints expose it to numerous diseases and possible injuries, which are covered in the next chapter of the paper.

Osteoarthritis (OA)

Definition

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the prevalent incendiary joint infections that influences millions of people worldwide. OA is a joint disease that results from the breakdown of joint cartilage and underlying bone (Hsu & Siwiec, 2018). Its symptoms include joint pain, stiffness, and decreased range of motion. Since the cartilage that ordinarily pads bones’ vicinity to one another has worn absent, bones are now squeezing against one another (Hsu & Siwiec, 2018).

Although osteoarthritis is treatable, joint harm is irreversible. Joint torment can be reduced and soothed by utilizing certain medications, partaking in regular physical activities, and maintaining a healthy weight (Zhang et al., 2010). OA risk factors include age, gender, body mass, earlier wounds, and family history. Indeed, according to Yuan et al. (2020), OA is most frequently diagnosed in the elderly population. Thus, it is essential to implement preventative measures to minimize the disease burden on at-risk populations.

Etiopathogenesis

A few professional associations have produced an agreed definition of OA. The National Organization for Joint Pain, Diabetes, Stomach Related and Kidney Infections and the American Foundation of Orthopedic Specialists are illustrations of such associations. Comprehensive definitions may satisfy curious readers but add little to our knowledge of what causes OA (Yuan et al., 2020). It is accurate concerning a common mistake doctors make but glosses over an important distinction between joint injury and articular cartilage loss.

OA develops when the body mounts a defensive response to mechanical stress in a joint. The existing criteria also fail to distinguish “garden variety” OA (the typical presentation of the ailment well-known to clinicians) and the many other joint diseases sometimes mislabeled as OA (Messier et al., 2021). Radiographic symptoms of arthritis identical to those observed in conventional OA can be elicited by rare systemic illnesses such as ochronosis or chondro epiphyseal dysplasia. It is a prevailing opinion that they should both be labeled OA because of their similarities. Due to its dynamic nature, OA defines categorization as primary or secondary. Instead, OA is invariably a secondary effect of some other condition or, more often, the result of multiple factors working together.

Arthritic Inflammation Classification

Arthritic inflammation falls into two basic categories: primary (idiopathic) OA and secondary (induced by something else) OA. Primary OA has multiple causes, including genetics, aging physiology, ethnicity, and biomechanics. Secondary OA has various causes, including trauma, dysplasia, viruses, inflammation, and metabolic variables.

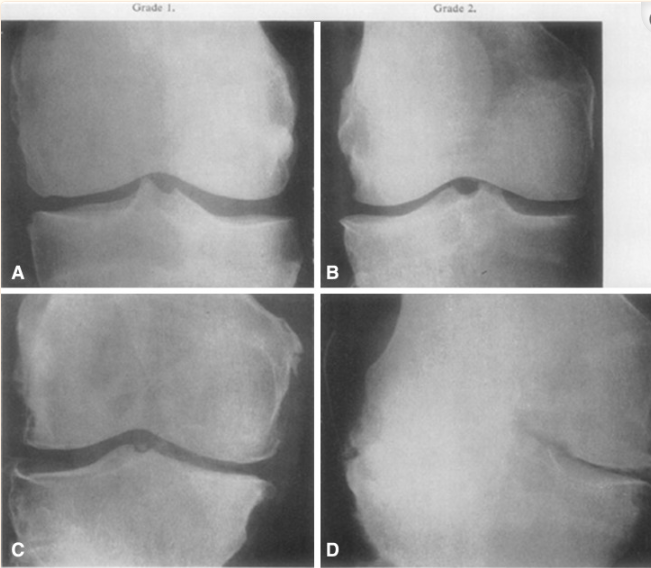

One of the most widely used diagnostic methods for OA is plain radiography, which has drawbacks (Kohn et al., 2016). Thus, the need for a classification scheme and a set of standardized radiographs led to the application of the Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grading scheme to better diagnose osteoarthritis of the diarthrodial joints.

Kellgren-Lawrence grading for no prevalence of radiographic characteristics is 0, while a grading of 1 indicates possible osteophyte lipping or possible joint spacing narrowing. Grade 2 is used to capture that the radiograph has identified osteophytes with a high possibility of narrowing joint spacing. KL grade 3 is applied to indicate the presence of more than one osteophyte, sclerosis, joint spacing narrowing JSN, and a deformity in the knee. Lastly, KL grade 4 indicates the presence of deformity of bones, osteophytes, severe JSN, and accelerated sclerosis.

Clinical Picture/Presentation of Knee OA

Figure 3 is a caption of Kellgren-Lawrence paper AP radiographs of the knee, taken initially. The Kellgren-Lawrence radiographs have been sequenced to capture all stages involved with knee OA. The first division marked A in the knee radiograph with Grade 1 in Figure 3 indicates the osteophytes and a resulting reduction in joint space. The second division marked B of the knee radiograph is consistent with apparent osteophyte formation and likely restriction of the joint space; thus, KL grade 2 (Kohn et al., 2016).

Section C of the Knee radiograph is indicative of KL Grade 3 arthritis. It is characterized by extensive osteophyte growth, sclerosis, and possibly deformed bone ends; the last sub-section of Figure 3 is D (Kohn et al., 2016). The knee radiograph indicates KL Grade 4, marked by extensive osteophyte growth, severe joint space restriction due to sclerosis, deformity, and the end of the bones.

Due to its polymorphic nature, OA can present in various ways, making an accurate diagnosis challenging. It is unclear how exactly mechanical, metabolic, biochemical, genetic, and immunologic processes contribute to the pathogenesis of OA, but all of these factors are thought to play a role (Kohn et al., 2016). Thus, joint pain reported by patients and consistent radiographic data have been central to many attempts to establish diagnostic criteria for OA.

Prevalence and Incidence

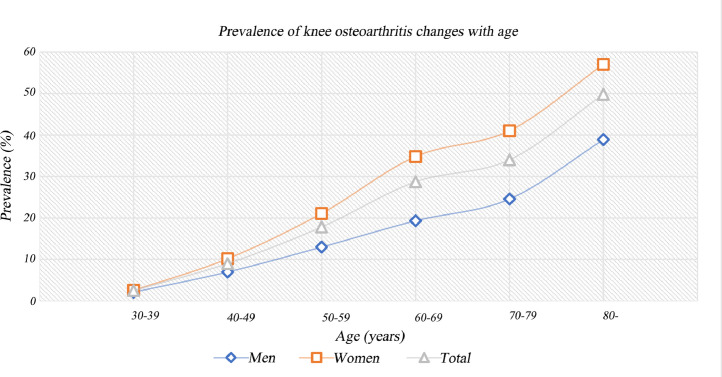

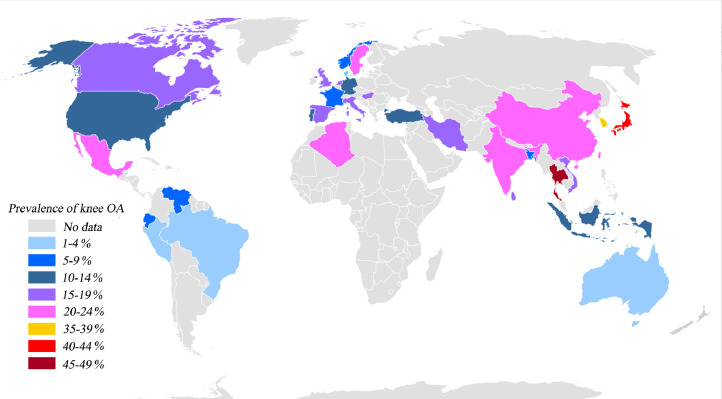

The rate of knee OA is predetermined by separating the entire number of modern cases by the overall number of at-risk person-years. The study by Cui et al. (2020) calculated the number of individuals with knee osteoarthritis universally, in any case of age, utilizing projections for the world’s populace from the UN Populace Division for 2020 with the analyzed data in graphical presentation as shown in figure 4 (Cui et al., 2020). The auxiliary result is chance proportions, which portray affiliations between hazard factors and the predominance and frequency of knee osteoarthritis based on the percentage representation of the prevalence against the age of both men and women genders. In addition, a further global presentation of the analyzed data has been represented in country formatting where data on the prevalence of knee osteoarthritis is available, as shown in Figure 5.

Risk Factors

OA is more predominant within the elderly populace. It is vague as to why males are at a better hazard than ladies for creating OA. Fat tissue’s chemical discharges may make joints more prone to aggravation. OA is more likely to be created after joint wounds, whether from mischances or sports (Kohn et al., 2016). OA can result from the determined joint push, such as that experienced amid labor or physical competition. Since OA runs in families, heredity influences the conditions that begin and move. Skeletal inconsistencies incorporate things like lost or distorted joints and cartilage. Insufficient press utilization has been connected to diabetes and other metabolic illnesses.

Knee-Diagnostic Procedures (X-ray, CT, MRI, Ultrasound, Arthroscopy)

Unfortunately, OA cannot be analyzed with a straightforward test. To diagnose it, a specialist may inquire about the therapeutic history, which incorporates a patient’s indications, illnesses, and medicines. On joint X-rays, bone thickness varieties caused by injury, remodeling, or goads can be watched (Steinmeyer et al., 2018). Joint degeneration in its early stages is ordinarily imperceptible on X-rays. Harm to the muscles, ligaments, and tendons close to a joint can be detected by an MRI (Mora et al., 2018).

Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI) can regularly assist restorative specialists in deciding the cause of a sore or solid joint. The back ligamentum mucosum repair through an anteromedial entrance requires the utilization of suture gadgets such as MRI that enter the meniscus at a point to ensure the blood vessels are not damaged. More may be required for security at the repair location (Innocenti, 2022). A vertical fasten explicitly connected to the tear can result in a quicker and more compelling meniscus repair. Meniscus expulsion could be a common sign of meniscus illness, and ultrasound is habitually utilized to distinguish it (Tayfur et al., 2021). On the back of the knee, injuries called “slope.” might be discovered.

Ultrasonography is progressively utilized for purposes other than determination, agreeing to later reports of effective ultrasound-assisted surgeries. Furthermore, blood tests are being performed to show any other likely causes of the side effects. A synovial liquid test is collected to identify irresistible or gout-related causes of joint inconvenience.

In addition, doctors can utilize CT filters to distinguish the break that has been maintained. These tests are, by and large, vital to way better portray a gap that has been identified on an X-ray or when an X-ray is typical, but the clinical side effects are still suggestive of a break (Zhang et al., 2020). These tests may be essential to survey the seriousness of a gap distinguished on an X-ray.

For patients under 50 suspected of having an inadequate break but do not qualify for a Medicare-reimbursable filter, CT is frequently utilized to screen for concealed breaks in an essential care environment when MRI is not a choice (Ma et al., 2018). On several occasions, CT is utilized in auxiliary care settings to hunt concealed breaks. Thus, a combination of tests and equipment might effectively diagnose the disease and its probable causes, ultimately facilitating treatment options.

Specialists perform knee arthroscopy by making minimal cuts within the skin and encompassing tissue to see the insides of the knee joint. The surgeon embeds a modest camera into the knee joint and guides the positioning of diminutive surgical devices. The surgeon must make a modest entry point in the skin to embed the arthroscope and surgical devices instead of the much bigger entry point required for open surgery. Sometimes, this may cut the time for a persistent patient to feel superior and continue their regular schedule in half.

Physiotherapeutic Interventions for Patients with Knee OA

Patient’s failure to follow prescribed regimens or other forms of treatment is one of the driving causes of recovery failure. Physical treatment appears helpful in clinical and factual settings, and regular walking is getting longer. Physical therapy helps people with knee OA, but further research is needed to compare the diverse muscle bunches in OA patients and sound controls. Indeed, according to Messier et al. (2021), strength training is one of the effective interventions capable of improving the mobility and overall functionality of the knee if followed regularly and for a sufficient period. More grounded quadriceps were related to less wear and strain within the patellofemoral joint, which is usually affected by OA.

Physical movement is suggested as a portion of the recovery arrangement as a means of physiotherapeutic interventions. Physical modalities utilized by these gadgets to treat patients have therapeutic outcomes. Power, light, warmth, cold, weight, and other shapes of vitality have been used to advance recuperating and lightening torment for thousands of a long time (Banger et al., 2020). Ultrasonic gadgets can boost tissue temperatures, which can help discharge firm muscles. Ultrasound has effectively treated OA, tendonitis, tenosynovitis, epicondylitis, bursitis, and other musculoskeletal clutters for decades.

As an alternative physiotherapeutic intervention approach to addressing knee OA, acoustic waves are utilized in ultrasound imaging. An electrical current creates them and generates warmth as they pass through tissues with changing resistivity. Ultrasonic is used in therapeutic diagnostics in both nonstop and beat modes (Varacallo et al., 2018). Persistent ultrasound produces tissue warming. Instead of persistently streaming, the control of the ultrasonic pillar swings between brief bursts of tall power and expanded interims of moo control. Whereas ceaseless ultrasound decreases development limitations, beat ultrasound treats intense torment and irritation (Khan et al., 2023). No treatment appeared to be discernibly more prevalent than the control treatment. Compared to ceaseless ultrasound treatment, beat ultrasound treatment was more compelling at decreasing applicable limits caused by knee OA.

Pharmacotherapy Treatments

The diagnosis of OA (OA) is still challenging due to the lack of symptoms in the illness’s initial, most destructive phases. Studies targeting this group should no longer be the exception. Studies comparing glucosamine hydrochloride and glucosamine sulfate salt are also required. Prescribers should know how frequently Hyaluronic acid (HA) should be injected, particularly in which patients, and how often to repeat the injection. Frankincense, devil’s claw, and herbal nettle extract are all used in OA therapies. Current research, sometimes open-label, tiny, and observational, cannot be utilized as evidence of effectiveness.

Surgical Treatments of Knee OA

Knee arthroplasty, known as knee substitution surgery, is used to reestablish joint work within the knee. The treatment, frequently known as an “add up to knee substitution,” has proven safe and effective (Khella et al., 2021). An intriguing group approach to treating knee joint pain is emphasized, as are the benefits, threats, and options to add to knee arthroplasty (Bhatia et al., 2013). The following are the available surgical treatments for Knee OA. Arthroscopy is when the specialist cuts within the knee, irrigates the joint and then rubs off any free cartilage. Within a joint knee, there is a contract window in which arthroscopy can be performed.

Contraindications for knee surgery include active infection, severe medical conditions such as heart disease or uncontrolled diabetes, and a pre-existing knee condition that has not responded to conservative treatments such as physical therapy and medications. Possible knee surgery complications may include infection, pain, swelling, numbness, stiffness, and the need for additional surgery. There is also a risk of nerve or blood vessel damage and the possibility of an allergic reaction to the anesthesia used during the procedure.

An osteotomy is a bone resection strategy commonly performed to rectify knee misalignment. People younger than 40 who participate in high-demand exercises like sports have customarily been at the center of this treatment. Osteotomies are now not as predominant as knee substitutions, which have increased ubiquity. However, if more progressive strategies for knee OA are available, osteotomy may discover a more noteworthy part in dominant future practices. For Cartilage Restoration Procedures, recovered harmed cartilage within the patient’s knee is surgically extracted, and solid cartilage cells are joined in their place. Whereas the promise of stem cell treatment for joint pain is energizing, the truth is that it should not be utilized to treat progressed cases of the illness.

Partial Knee Replacement is a surgical strategy in which the unhealthy or harmed area of the knee is supplanted. Other potential areas are the patellofemoral (knee cap) joint and the femur-tibia (thigh bone) junction (femoral-tibial). These procedures are favored since they promote faster recovery and require less anesthetic attention. The question of who constitutes the most noteworthy candidate for these strategies is constantly evolving. It is too imperative to consider the degree of distortion or the sickness’s location.

Total Knee Replacement (TKR) surgery is prescribed for patients with progressed knee arthritis who have not found help from less invasive strategies. The strategy includes severing the closes of the shinbones and capping the remaining bone with metal or plastic. This surgical operation has an exceptionally high victory rate compared to other surgical procedures. Nearly all those with a TKR substitution will be satisfied with the results at the twenty-year check.

Pre and Post-Operative Rehabilitation

Preoperative rehabilitation is essential for weight-bearing joints, such as the knees and hips, to feel better and have fewer wounds. Braces and orthotics may also help osteoarthritic joints. Drugs such as verbal torment relievers, topical pain relieving, and corticosteroids can also help reduce joint torment. The specialist will decide how often and how many infusions are needed. Weight-bearing joints, such as the knees and hips, may benefit the most from this.

Restorative workout regimens for post-operative rehabilitation can benefit individuals with progressed knee OA throughout the peri-operative period. Surgery, including the heart, lungs, and knee, may require post-operative recovery. Physiotherapy is valuable for tending to a wide range of post-surgery complications. Post-operative rehabilitation after surgery is focused on making a difference in patients’ recapturing quality and portability, avoiding other well-being issues, and returning to doing the things they cherish.

Physical treatment (PT) plays a crucial part in restoration after surgery by encouraging the healing of muscle work, an extension of movement, and mental well-being. The patient’s capacity to move and utilize the joints, muscles, and respiratory framework after surgery is enormously made strides by physical treatment and other recovery shapes.

Conclusion

OA is a condition that affects the life structures of the fundamental bone and weakens the cartilage that lines joints. It can cause torment, firmness, and edema, and some individuals have become so disabled that they cannot work in everyday life or hold down work. Multimodal approaches, such as pain relievers, calorie confinement, and self-management, are commonly used to treat OA side effects. Specialists suggest that grown-ups lock in indirect levels of physical movements, such as cycling, swimming, and strolling. Weight loss and maintenance can help to play down OA indications, make strides in execution, and expand joint well-being.

References

Abid, M., Mezghani, N., & Mitiche, A. (2019). Knee joint biomechanical gait data classification for knee pathology assessment: a literature review. Applied bionics and biomechanics. Web.

Angin, S., & Simsek, I. (Eds.). (2020). Comparative kinesiology of the human body: normal and pathological conditions. Academic Press. Web.

Antico, M. (2021). 4D ultrasound image guidance for autonomous knee arthroscopy (Doctoral dissertation, Queensland University of Technology). Web.

Banger, M. S., Johnston, W. D., Razii, N., Doonan, J., Rowe, P. J., Jones, B. G.,… & Blyth, M. J. (2020). Robotic arm-assisted bi-unicompartmental knee arthroplasty maintains natural knee joint anatomy compared with total knee arthroplasty: a prospective randomized controlled trial. The Bone & Joint Journal, 102(11), 1511-1518. Web.

Bhatia, D., Bejarano, T., & Novo, M. (2013). Current interventions in the management of knee osteoarthritis. Journal of pharmacy & bioallied sciences, 5(1), 30. Web.

Cui, A., Li, H., Wang, D., Zhong, J., Chen, Y., & Lu, H. (2020). In population-based studies, global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis. EClinicalMedicine, 29, 100587. Web.

Holm, P. M., Juhl, C., Culvenor, A. G., Whittaker, J. L., Crossley, K. M., Roos, E. M.,… & Bricca, A. (2023). The effects of different management strategies or rehabilitation approaches on knee joint structural and molecular biomarkers following traumatic knee injury–a systematic review of randomized controlled trials for the OPTIKNEE consensus. Journal of Orthopaedic & Sports Physical Therapy, (0), 1-27. Web.

Hsu, H., & Siwiec, R. M. (2018). Osteoarthritis, Knee. StatPearls. Web.

Innocenti, B. (2022). Chapter 13 – Biomechanics of the knee joint. Academic Press. Web.

Khalfaoui S & Abbassi EI M., (2019). Rehabilitation of Knee Arthroplasty. Austin Physical Medicine. Web.

Khan, S. A., Parasher, P., Ansari, M. A., Parvez, S., Fatima, N., & Alam, I. (2023). Effect of an Integrated Physiotherapy Protocol on Knee Osteoarthritis Patients: A Preliminary Study. In Healthcare, 11(4), 564. Web.

Khella, C. M., Asgarian, R., Horvath, J. M., Rolauffs, B., & Hart, M. L. (2021). An evidence-based systematic review of human knee post-traumatic osteoarthritis (PTOA): Timeline of clinical presentation and disease markers, comparison of knee joint PTOA models and early disease implications. International Journal of Molecular Sciences, 22(4). Web.

Kohn, M. D., Sassoon, A. A., & Fernando, N. D. (2016). Classifications in brief: Kellgren-Lawrence classification of osteoarthritis. Clinical Orthopaedics and Related Research, 474, 1886-1893. Web.

Lippert, L. S., & Minor, M. A. D. (2017). Laboratory manual for clinical kinesiology and anatomy. FA Davis. Web.

Ma, J. X., Zhang, L. K., Kuang, M. J., Zhao, J., Wang, Y., Lu, B.,… & Ma, X. L. (2018). The effect of preoperative training on functional recovery in patients undergoing total knee arthroplasty: a systematic review and meta-analysis. International Journal of Surgery, 51, 205-212. Web.

MacConaill, M. A. (2022). Joint. Encyclopedia Britannica. Web.

Messier, S. P., Mihalko, S. L., Beavers, D. P., Nicklas, B. J., DeVita, P., Carr, J. J.,… & Loeser, R. F. (2021). Effect of high-intensity strength training on knee pain and knee joint compressive forces among adults with knee osteoarthritis: the START randomized clinical trial. Jama, 325(7), 646-657. Web.

Mora, J. C., Przkora, R., & Cruz-Almeida, Y. (2018). Knee osteoarthritis: pathophysiology and current treatment modalities. Journal of pain research, 2189-2196. Web.

Shirley, P. Y., & Hunter, D. J. (2015). Managing osteoarthritis. Australian Prescriber, 38(4), 115. Web.

Standring, S., & Gray, H. (2020). Gray’s anatomy: The anatomical basis of Clinical Practice. Elsevier.

Steinmeyer, J., Bock, F., Stöve, J., Jerosch, J., & Flechtenmacher, J. (2018). Pharmacological treatment of knee osteoarthritis: Special considerations of the new German guideline. Orthopedic reviews, 10(4). Web.

Stetter, B. J., Ringhof, S., Krafft, F. C., Sell, S., & Stein, T. (2019). Estimation of knee joint forces in sport movements using wearable sensors and machine learning. Sensors, 19(17), 3690. Web.

Tayfur, B., Charuphongsa, C., Morrissey, D., & Miller, S. C. (2021). Neuromuscular function of the knee joint following knee injuries: Does it ever get back to normal? A systematic review with meta-analyses. Sports medicine, 51, 321-338. Web.

Teague, C. N., Heller, J. A., Nevius, B. N., Carek, A. M., Mabrouk, S., Garcia-Vicente, F.,… & Etemadi, M. (2020). A wearable, multimodal sensing system to monitor knee joint health. IEEE Sensors Journal, 20(18), 10323-10334. Web.

Varacallo, M., Luo, T. D., & Johanson, N. A. (2018). Total knee arthroplasty techniques. StatPearls. Web.

Yuan, C., Pan, Z., Zhao, K., Li, J., Sheng, Z., Yao, X.,… & Ouyang, H. (2020). Classification of four distinct osteoarthritis subtypes with a knee joint tissue transcriptome atlas. Bone Research, 8(1), 38. Web.

Zhang, L., Liu, G., Han, B., Wang, Z., Yan, Y., Ma, J., & Wei, P. (2020). Knee joint biomechanics in physiological conditions and how pathologies can affect it: A systematic review. Applied bionics and biomechanics. Web.

Zhang, W., Doherty, M., Peat, G., Bierma-Zeinstra, M. A., Arden, N. K., Bresnihan, B.,… & Bijlsma, J. W. (2010). EULAR evidence-based recommendations for the diagnosis of knee osteoarthritis. Annals of the rheumatic diseases, 69(3), 483-489. Web.