Stories have a crucial role in discussions about a crime. Every time an occurrence is considered a “crime,” stories are created, and responses are decided. Events are reported, blame is assigned, explanations are sought, and potential conflicting theories are weighed. In other words, narratives are created and rejected to challenge crime. Crime formation occurs according to linguistic and cultural patterns called narratives, which coordinate criminal activity. The idea behind “patterns” is that stories do not just happen (Feilzer, 2020). They are decided upon and negotiated through institutional and social procedures. In the long run, these processes can lead to the establishment of some narratives (Althoff et al., 2020). Others will fade away or be forgotten, which is a contentious process. This collection aims to shed light on the little-examined question of what it means to relate narratives and conflicts in the context of crime and punishment.

For example, updating press releases and managing the context of such actions are only two of the numerous valuable chances the Internet offers the police to publicize their operations. In the modern world, the police’s use of social media goes well beyond informing the public and publicizing their operations (Feilzer, 2020). Police press agents work with field agents to garner support for ongoing investigations (Colbran, 2018). Delivering public safety warnings and gathering intelligence from the broader public are two ways that police personnel will disseminate information about suspects. Before social media, police agencies mostly used the media to interact with the public. The decision to engage in news-making by the audience or the request to do so is growing. Helping the public is successful because they are urged to immediately give tips or recordings to the police from their mobile devices via social media.

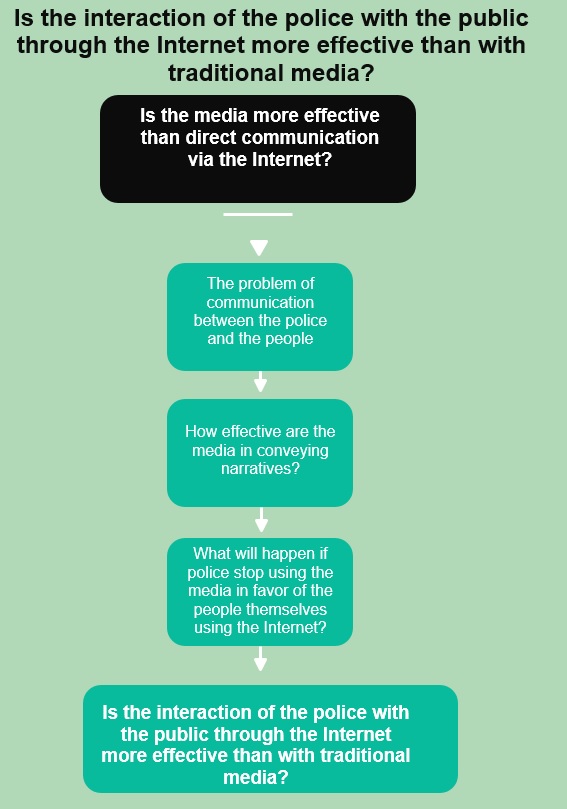

The influence of social networks on the existing interaction between the police and the media must be studied in light of recent technical, cultural, and social developments. The cops can altogether avoid traditional media thanks to social media usage (Feilzer, 2020). From the very first, it is logical to presume that police limits have most negatively impacted the national press on journalist interaction. As a result, the reports emphasize the IPU’s social media usage (Colbran, 2018). The study should be supported by empirical research, such as interviews with top police officers and Media and Communications Authority representatives (Althoff et al., 2020). The query should discuss both historical and contemporary facts, as well as examine ties to crime journalists. This is especially true for journalists who work for major national news organizations in the print, broadcast, Internet, and Internet media.

Stories have a crucial role in discussions about a crime. Every time an occurrence is considered a “crime,” stories are created, and responses are decided. Events are explained, roles are assigned, reasons are sought, and many interpretations are considered. In other words, narratives are created and rejected to challenge crime. Crime formation occurs according to linguistic and cultural patterns called narratives, which coordinate criminal activity. By “patterns,” we mean that narratives are formed and negotiated via social and institutional processes rather than just existing. In these processes, sure tales can be sustained over time, while others will be forgotten or fade away. This is a contentious procedure. This research question aims to shed light on the little-examined topic of what it means to relate narratives and conflicts in the context of crime and punishment.

The idea of a trust hierarchy is crucial in determining how the media and the police interact. It is a paradigm that takes for granted that the governing elites in any society have the Authority to decide how things are. This paradigm inspired an early study on criminal reporting (Althoff et al., 2020). However, later research has placed more emphasis on the significance of economic considerations, organizational behavior, and working relationships (Colbran, 2018). In the creation of news, this organization is significant between sources and reporters.

The interaction between local and national crime reporters and the police should be taken into account while researching this topic. This specifically applies to the regional police forces, especially the officers in charge of public relations. A global media crisis and the growth of corporate police communications are related. The asymmetrical connection between the media and the police will only worsen as new technologies and social media development. Forces’ strategic decision is probably to forgo traditional media in favor of direct communication. However, to thoroughly examine the matter, it is equally important to examine how the opposing side produces news. Members of the public can occasionally provide information using new technology that contradicts the official account of events.

References

Althoff, M., Dollinger, B., & Schmidt, H. (2020). Fighting for the “Right” Narrative: Introduction to Conflicting Narratives of Crime and Punishment.Conflicting Narratives of Crime and Punishment, 1–20.

Colbran, M. P. (2018). Policing, social media and the new media landscape: can the police and the traditional media ever successfully bypass each other?Policing and Society, 30(3), 295–309.

Feilzer, M. Y. (2020). Public Narratives of Crime and Criminal Justice: Connecting ‘Small’ and ‘Big’ Stories to Make Public Narratives Visible. Conflicting Narratives of Crime and Punishment, 63–84.