The Mongol invasions of Japan had a vast and profound historical impact. First, the failure to conquer Japan marked an end to the expansion of the Mongol empire. Second, the Mongols’ military attempts to subdue the Japanese required additional resources, which is why the Mongol leader, the Great Khan, who had assumed the position of the Chinese emperor, extensively used this position while also demanding assistance from Korea, his tributary. The Mongol invasions of Japan demonstrated how tightly interconnected the three countries—China, Korea, and Japan—had become during the early period of the Yuan rule.

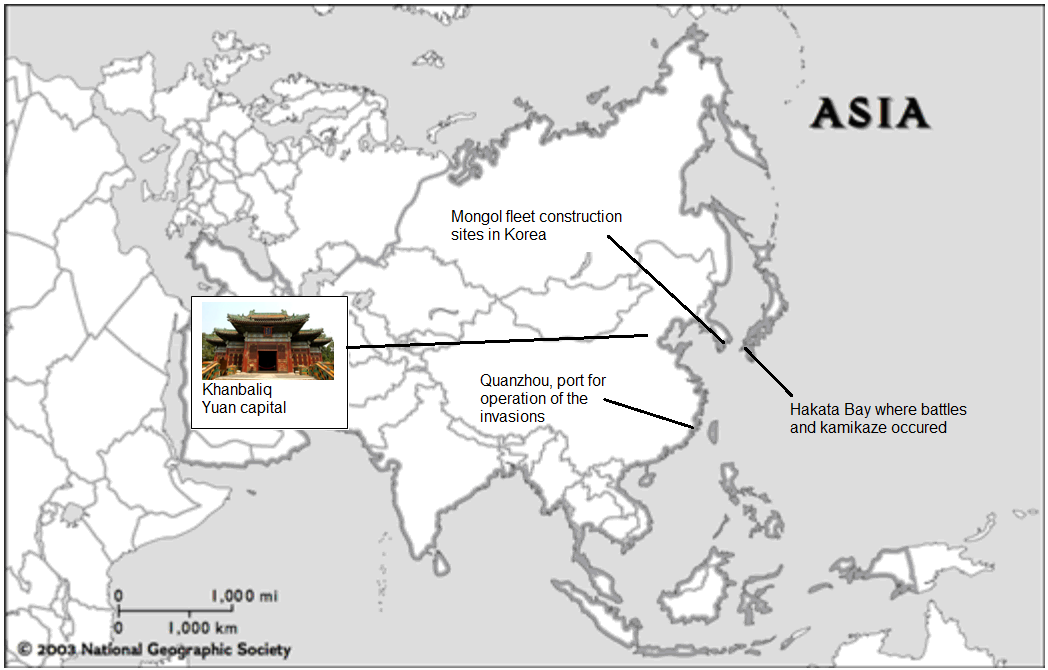

These invasions can be regarded as not only Mongol in nature but also Chinese. Kublai Khan declared himself a Chinese emperor, possessing the Mandate of Heaven, which meant placing the dynasty among other Chinese imperial dynasties in the historical records according to the concept of dynastic cycles (Ebrey and Walthall 17). Furthermore, he ruled the empire in accordance with the Chinese institutions of power. It can be said that the invasions of Japan started in Khanbaliq, the capital of the Great Khan’s empire, a place that he had established and that later became Beijing (see fig. 1; the picture depicts a palace built by Kublai Khan in his capital). It was in Khanbaliq that the emperor planned the invasions and ordered other parts of China to prepare for military action. The main port of operation was planned to be Quanzhou, a major southeastern port city (see fig. 1).

To build ships for the fleet, Kublai Khan addressed himself to the tributary Korea. On the southeastern shores of that country, the necessary number of ships was constructed (see fig. 1). Korea made a major contribution to the creation of the fleets for both Mongol invasions.

However, the invasions were a failure. One of the key factors involved was the intervention of natural (or supernatural) forces. The advance of the first Mongol fleet was significantly impaired by a typhoon, and approximately half of the second fleet was destroyed by another typhoon. The Japanese called these typhoons kamikaze, which means divine wind (Ebrey and Walthall 196). The key battles occurred in the Hakata Bay in Japan (see fig. 1). The Mongol military forces turned out not to be strong enough to subdue the Japanese.

Land warfare took place during the invasions, as well. The Japanese depiction of the Mongol warriors afterward is remarkable. These depictions showed the Japanese warriors as rather flamboyant and even inclined to luxury. Their armor and garments were bright and noticeable. Also, it can be seen in the depictions that some warriors dyed their horses or drew patterns on them. In addition, various decorations were applied; one of the warriors is seen to have a tiger-skin saddle blanket on his horse (“Takezaki Suenaga’s Scrolls of the Mongol Invasions of Japan.”). The scrolls show dynamic battle scenes, including one in which many warriors are running or galloping on their horses toward the Mongol army (however, it may not be immediately noticed by a Western reader unless he or she knows that the Japanese scrolls should be read from right to left). According to the scrolls, the Mongol warriors were dressed in a simpler manner and mostly wore monotonous robes with little or no decoration. Even the figure of a Mongol general wearing red clothes and some decorations, later added to the scroll as part of retouching, appears less remarkable and less bright than the figure of practically any of the Japanese warriors represented.

The Mongol invasions of Japan reflected the political processes in East Asia during the early period of the Yuan rule. The Mongols were ruling China, and the Great Khan as their ruler was simultaneously the Chinese emperor with the power to fully use the country’s resources for foreign invasions. As a tributary, Korea had to submit to Kublai Khan’s orders. Japan was closely connected to both countries in terms of religion and previous cultural exchange (Deal 218), but the resistance of the Japanese to the invasions was remarkable and stopped the expansion of the Mongol empire.

In Japan, the promotion of Confucianism by the elite occurred during the Yamato period (Ebrey and Walthall 122). This effort was part of the ruling class’s attempts to attract to the court those who had access to the elite culture of China; these included Confucians but also referred to Buddhists, Daoists, and various artists such as painters, writers, and musicians. However, the specific characteristic of the Confucian influence consisted in the way the Japanese rulers adopted, to an extent, the Confucian vision and system of power. During the early period of the Japanese state, rulers did not fully comprehend the importance of literacy. The cultural exchange that promoted literacy in Japan was rather associated with Buddhism (as seen in the visits of Buddhist monks and the delivery of Buddhist texts from China and Korea); however, it is Confucianism that stresses that officials should be educated. Therefore, members of the Japanese elite who were interested in establishing a Confucian system of power in the country promoted Confucianism over Buddhism.

Confucian influence was also evident in Korea. For example, Confucian ideas can be detected in the Ten Injunctions issued by King T’aejo in the tenth century (Lee 263). Overall, it can be argued that the injunctions are largely Buddhist, which is particularly true in terms of their ethical components. For example, they state that, instead of universally right and wrong concepts, there are rather different opinions and perspectives, and what is right for someone can be wrong for someone else. This idea implies creating a flexible administration system instead of a rigid one. However, the third injunction states that imperial commands must be immediately obeyed. In addition, injunction four states that decorous behavior is the main principle of governing people. This concept, unlike the Buddhist vision, refers to Confucian principles such as the principle of ruling people by virtue and applying moral force as the main instrument of power for a ruler. The promotion of these Confucian beliefs was used by the Korean elite to strengthen the state because Confucianism fundamentally implies strict subordination and unquestionable submission to those in power. This perspective was also evident in the story of Gangsu, a Korean aristocrat from the low-aristocracy class who attained an exceptionally high position as a scribe in the royal court for his success in managing correspondence with China (Ebrey and Walthall 109). When Gangsu was growing up, he was asked to choose to study either Buddhism or Confucianism. He chose the latter because he thought that Buddhism dealt with the heavenly world, while Confucianism dealt with the world of men, which was the reason, as he was going to be living in the world of men, that he should choose to study Confucianism. This vision of Confucianism as a way to succeed demonstrates that Confucian teachings were promoted by the elite as a means to power.

In China, of course, the differences between Confucian and Buddhist beliefs were the most vivid because the country was the home of Confucianism as well as the place from which Buddhism further spread to other parts of East Asia. The motivation of the elite to promote Confucianism was similar to the motivations seen in Japan and Korea. There was the need to rule a large empire, and this could only be done by establishing and maintaining a strong, centralized system of power, which could not be essentially supported by Buddhist beliefs but could be supported by Confucian beliefs. For example, this vision was reflected in the work of Han Yu (Ebrey and Walthall 90), a writer and thinker who argued that the emperor should be more devoted to old Confucian principles and should not encourage the spread of Buddhism (which was largely voluntary, as there were no forced conversions). Han Yu’s idea was that the fragmentation of the state was bad, and a centralized government system should be sustained, for which purpose, young men should study Confucianism and adhere to its principles.

The exposure of East Asia to European influences in the 16th–18th centuries was a significant historical factor, and the topic that should be particularly addressed in this regard is the manner in which the elite in the three countries (China, Japan, and Korea) embraced this exposure. In China, to begin with, trade was the most-appreciated aspect. Historically, Chinese leaders always strove to establish economic relations with their neighboring countries as well as those that were more distant. This factor can be seen both in the history of the Great Silk Way and the specific characteristics of the Chinese tributary system. The latter, despite being called by some historians a fiction, was actually a system of mutually beneficial economic relations and not mere attempts to force a neighbor into submission; China was more interested in the former because this type of system allowed exercising cultural influence and power over such states as Korea or even more distant nations like the Turks (Wang 134). Portuguese merchants started coming to China for the purpose of trade in the early 16th century (de Bary and Lufrano 151), and this was embraced by the elite.

Another idea that was welcomed in China with the arrival of the Europeans was science. Chinese science had been developing separately from that of the Western world (although not fully separate from all other countries, even those that were far away, because of the influences of the Great Silk Way), and it was highly developed in certain aspects by the advent of the more extensive European exposure in the period under consideration; however, there were still things to learn from the Westerners. For example, the famous Jesuit missionary Matteo Ricci, living in China, wrote not only on theology but also Western mathematics, astronomy, and geography, aiming for non-Western readers; his texts were later delivered to Korea and Japan (Ebrey and Walthall 268). This influence was important because scientific and technical knowledge could be used by the elite to strengthen their power by applying better regulations and systems of calculation.

Finally, in China, many of the products the Europeans had brought were adopted and cultivated. According to Ebrey and Walthall, such products as corn, sweet potatoes, chili peppers, and tobacco (265) were introduced by Portuguese traders (it is noteworthy that many of those products were not native to Europe as they had earlier been brought to Europe from the Americas). This is a major factor of influence and exposure because adopting other countries’ foods transforms the relationships among countries.

Similar examples can be observed in Japan, as well. In particular, the Japanese scholars learned a great deal from the Dutch academics who came to Japan. In Japan, unlike in China, the superiority of Western science over Japanese science was widely recognized, which enabled the growing influence of the Netherlands (Sugita 20). Specific areas in which Japanese scholars were interested in learning from their Dutch counterparts were medicine and astronomy. The exposure was regulated by the government, and in some parts of Japan such as Nagasaki, European scholars who stayed in the city could be contacted by locals only by obtaining permission. In other parts, however, it was easier to access a Western scholar, such as in Edo, and Japanese scholars used these opportunities to have conversations with the foreigners using the assistance of interpreters. Possessing European books was prohibited, but it is known that many scholars obtained them and read them illegally. The development of science in Japan was largely facilitated by these contacts and this exposure.

Another example from Japan involves religious influence. Many Europeans who came to East Asia during the period under discussion were missionaries, and they strove to convert the locals to Christianity. Although Christianity was further opposed by the governments and elites (a point to be discussed at greater length), the initial introduction of Christian teachings resulted in extensive waves of voluntary conversions in many parts of East Asia, including Japan. Furthermore, the spread of Christianity was not limited to the common people; since even some samurais and domain lords accepted the Christian faith (Lu 196), it can be said that, in the beginning of the country’s exposure to missionary endeavors, the Japanese elite embraced Christianity.

Also, the exposure to European influence in Japan was manifested in trading. During the three centuries under discussion, the regulations varied greatly, as Japanese rulers strove to optimize trade with the West and were still suspicious of its influence. However, it could not be denied that the presence of Portuguese and later Dutch ships in the waters between Japan and China provided many advantages for more successful trading. In fact, during the period in which international relations were favorable, the Portuguese even traded between China and Japan by bringing Japanese silver to China (Ebrey and Walthall 267). The Japanese elite embraced such opportunities and willingly cooperated with the Europeans.

Korea, in contrast, was more suspicious and less welcoming to both missionaries and traders (Ebrey and Walthall 269). Several attempts on the part of Europeans to establish favorable relations with the country failed. However, Korea, like China and Japan, was interested in some things it could take from the Westerners, for example, the Western calendar. In Korea, the king was traditionally responsible for establishing the calendar for each year as the concept of the king’s power was connected to his responsibility for connecting the world of humans to the supernatural world; therefore, he was supposed to predict the events of the astronomic year (Ch’oe et al. 119). For example, the sun, the moon, or another celestial body not being found at an indicated moment in the positions earlier predicted by the king undermined the superiority of the king’s power. This fact can explain the interest in the more accurate Western calendar.

The Korean exposure to European influence was generally known in Korea as “Western Learning” (Ebrey and Walthall 260), and a further component, along with science, was Christianity. Korea experienced this exposure later than and, in a sense, to a lesser extent than China or Japan; however, many texts by Korean scholars were dedicated to issues of Christianity. It can be argued that the Korean elite used the spread of Christianity as something to oppose in order to reinforce the existing order in the country. Christian teachings were used by Korean scholars to re-establish Confucian principles and values by contrasting the latter to the former.

In fact, the fate of Christianity in the three countries during the period being considered deserves particular attention. First, it should be noted that Western science and knowledge were mostly welcomed and appreciated in East Asia, and the trade with the Europeans was promoted, as well, but the attempts of the Westerners to suggest changing the political or governmental systems as well as their attempts to promote the Christian faith were received with hostility by most of the elite of China, Korea, and Japan. The general idea was that Confucianism was profoundly connected to the way of ruling a country, and the distribution of power among officials as well as the highest institutions of power, such as the royal or imperial courts, were largely based on Confucian teaching. Therefore, Christianity was perceived by some as not only a threat to Confucianism as a religion but also to Confucianism as the way to rule and the form of the state.

For example, in China, Yang Guangxian argued that Christianity did not comply with the Confucian principles of five relationships, meaning the relationships between parents and children, rulers and ministers, spouses, siblings, and friends. In fact, the very idea of Jesus’ immaculate conception and being raised by Joseph is anti-Confucian (de Bary and Lufrano 151). In Korea, Catholicism and the concept of deities were criticized and opposed; moreover, Western education was called “laughable” (Lee 130) because it failed to recognize the holistic nature of education as recognized in Korea. In Japan, as part of the effort to establish secular rule, missionaries were expelled from the country in the late 16th century (Lu 196), although Christianity had been flourishing there for more than 100 years.

In Japan, the residence of the emperor was traditionally regarded as the capital. Over the course of history, the capital repeatedly moved, and the reasons could be political or symbolic. In the early 8th century, the capital was moved to Nara in the central part of the country. The city was prepared to become the capital of the empire, and various symbolic attributes of power were applied to it. The imperial palace was built according to the Chinese cosmological principles to reinforce the power of the ruler and not to drain it, and the entire city was divided into two symmetrical parts to symbolize the division of ministers under the ruler (Ebrey and Walthall 120). However, the emperor became frustrated at the number of demands for favor that he received in Nara, and the decision was made to move the capital Heian-kyo (Kyoto) in the western part of the country, where it remained the seat of the imperial court for more than one thousand years.

However, the official capital was not always the political center of Japan. In the late 12th century, a military regime was established, centered in Kamakura, a city situated on the southeastern coast of Japan, a week’s journey from Kyoto and close to modern-day Tokyo. Kamakura had none of the grandeur of the capital (Ebrey and Walthall 183), but this was the place where military leaders lived as they had left the burden of conducting ceremonies and practicing rituals to the court while they were exercising the real political power.

Later, shogun Takauji built his headquarters in the Muromachi district in Kyoto to be closer to the emperor and oversee the activities at court. However, unlike the Kamakura period, in which the emperor and the shogun had ruled the country together, neither the emperor nor the shogun exercised effective governance in Japan (Ebrey and Walthall 214). Therefore, it can be argued that the Muromachi district was a political center only to a limited extent, like the imperial court.

The Edo period began in the 16th century and was marked by a new transition in terms of the political center of Japan. Tokugawa Ieyasu turned a village on the coast into a castle town for himself; it was his residence and supported his rule. The town later became Tokyo, the eastern capital (it is situated northeast of Kyoto). This new change of the actual capital was important because the Tokugawa shogunate was different from previous military regimes as Tokugawa shoguns implemented consistent policies to introduce serious changes to the political and social systems of Japan. The fact that they established a new political center from which they ruled Japan showed that Tokugawa shoguns had defeated all their enemies in the struggle for power in that country.

Works Cited

Ch’oe, Yong-ho, et al. Sources of Korean Tradition. Vol 2, Columbia University Press, 2000.

De Bary, Theodore, and Richard Lufrano. Sources of Chinese Tradition: From 1600 Through the Twentieth Century. Columbia University Press, 2000.

Ebrey, Patricia B., and Anne Walthall. East Asia: A Cultural, Social, and Political History. Wadsworth, 2014.

Lee, Peter H. Sourcebook of Korean Civilization. Vol. 1, Columbia University Press, 2010.

Lu, David, editor. Japan: A Documentary History: The Dawn of History to the Late Tokugawa Period. M. E. Sharpe, 2001.

Sugita, Genpaku. Dawn of Western Science in Japan. Translated by Ryozo Matsumoto and Eiichi Kiyooka, Hokuseido Press, 1969.

Wang, Zhenping. Ambassadors from the Islands of Immortals: China-Japan Relations in the Han-Tang Period. University of Hawaii Press, 2005.