Introduction

Islamic law today is the product of almost fourteen centuries of continuous development commencing early in the seventh century AD. The understanding of the general term ‘law’ used in English is only a small part of a much wider concept in the Islamic teachings – Shari’ah. The term Shari’ah is relatively comprehensive and has a much wider scope which is not possible to be rendered the use of a single word in English. The term Shari’ah may be complemented and closely approximated to the term ‘religion’ where Shari’ah could be considered as the prescriptive side of religion. Shari’ah not only covers various aspects of human life in this world but also provides guidance for the life here after. It therefore deals with providing reasoning for a particular human behaviour and expectations of human beings from following a particular way of life. It consists of teachings from the Islamic Holy Book and Hadith regarding preferred culture, principles of religion and ethics, code of law and other disciplines of life which are considered integral part of human life helping humans to develop their beliefs, intelligence and perform different acts of life which help them in building relation with God and other human beings.

In the last two decades, the internet and e-technology have contributed tremendously by shaping up the ways in which communications are taking place and have really turned the face of world around where distances have become meaningless and tons of information is easily and freely available on the net. The trend of the use of information technology has not been limited to certain countries but it has been spread without boundaries. In Islamic world the technology had been till recently used mainly for the purpose of spreading Islamic education and propagation, defend negativities against the religion and other religious purposes. In addition to these there has been limited application of technology for commercial and entertainment purposes.

The Qur’an is considered to be the most revered of books in Islam and is frequently regarded as the Holy Book. It serves to guide Muslims in all walks of life and in all ages. Analogical expressions allow the book to be more than productive and far more than adequately adaptable for all modern innovations. Since modern day knowledge has become increasingly integrated with innovations in Information Technology, it comes as no surprise that the Qur’an advises its followers to pursue knowledge regardless of the hurdles that come forth.

The very first verses of the Qur’an were ones that called the follower to read in the name of his Lord and Cherisher and to acknowledge his Lord’s uniqueness by acknowledging the fact that He is the supreme creator and He created all mankind from nothing more than a congealed clot of blood.

As information technology represents a shift to new areas of knowledge, by implication, it is an area that is important for Muslims to learn about, and explore its potential for good purposes.

The Qur’an encourages its followers to engage actively in work that is productive to them. In this regard, the Qur’an gives frequent reference to elements such as business and other commercial activities as well as direct references to trade at numerous occasions. According to the Qur’an, engaging in productive activities should be perceived as a duty and no doubt remains when the Prophets Mohammad’s (P.b.u.h) saying is considered in which he has clearly stated that a person seeking knowledge is a person who God will lead to heaven and in order to do so, he shall make sure that there are angels by the individual’s side to guide him.

In another instance, the Prophet referred to the return of seeking knowledge as a reward that would be far more than what the individual initially had in mind when he began his pursuit of knowledge but in the event that the individual did not manage to make it through, the person would still be rewarded.

We can infer from these verses and numerous other verses that the Qur’an and the Sunnah of the Prophet Mohammad (P.b.u.h) that there is an extensively high degree of importance given to the pursuit of knowledge in Islam and this leads us to concur that no part of Shari’ah denounces the pursuit of knowledge in any way. It is essential to note that this understanding does not exclude the use of technological innovation as a means to facilitate the process of the pursuit of knowledge since the Shari’ah has not distinguished between any specific means or technologies that can be used. Hence, by doing so, the Shari’ah gives room to the use of all forms of technology, including those that are generally brought into use in the case of e-commerce transactions. Hence, if this particular perspective was considered to be empirical, the Shari’ah approves the use of technology that is generally brought into use during e-commerce transactions.

However, the development of information technology has led us to one of the most significant revolutions in our lives in the form of a close-knit society based on the internet. This has had a direct implication on the methods through which businesses are conducted in everyday life and elements such as competition commerce and businesses in general are perceived. In fact, the global presence of the Internet serves to stimulate buying and selling through the E-Commerce platform. E-Commerce here is being regarded as the actual process through which electronic buying and selling is carried out through multilateral use of the networking, digital technology and the internet.

However, it is essential to highlight at this point that even though e-commerce has taken on the form of a global phenomenon, it is still one that many Muslims do not make use of in light of a deficiency of information on the subject of the Islamic perspective on transactions made through e-commerce.

Since little has been done to regulate this phenomenon according to the Islamic legal system, the main aim of the thesis is to establish that the general principles for ordinary sale contracts in Islamic law are appropriate to govern the formation of electronic sale contracts. The second aim is to provide a resource for all readers, researchers, interested individuals and organizations doing business by e-commerce contracts under Islamic law, whether they approach it from a business, information technology or legal background.

Issues of the legality of the formation of e-sale contracts in Islamic law shall be considered and shed light upon in an attempt to reflect on the benefits that e-commerce holds for Muslims across the globe and to elaborate on the legality of the use of e-commerce in the frame of reference of Islamic principles. Regarding transactions via e-sale contract, the issues of offer and acceptance through the internet will be studied to clear Muslim doubts as to the Islamic law’s approach to the valid formation of the e-sale contract. Countless seminars and conferences have been held alongside even more books on the subject. With the challenge to fulfill this gap, the thesis shall take on a perspective through which it shall elaborate on the e-sale contract in light of Islamic perspectives and the potential hurdles that can come forth in the development of the same.

It is beyond the scope of this thesis to examine all kinds of contracts recognised in the Islamic law. The centre of attention in the case of this thesis shall be the sale contract. The part of the thesis constituting the legal framework shall relate to the laws of sale contract as the contract par excellence in Islamic law. A model shall be used in the form of the fundamental principles of the e-sale contract in Islamic law. It shall be considered that this contract is one upon which other contracts rely as per Islamic law. Moreover, the sale contract is dealt much more extensively in fiqh (science of the Shari’ah) writing than other contracts, which are presumed to be regulated by analogy to it where appropriate.

The thesis will examine and analyze the relevant literature and legislation. It will argue that the following legal issues may arise when forming sale contracts in an electronic environment under the general principles of ordinary sale contracts in Islamic law:

- Has a valid offer and acceptance been formed in the e-sale contract?

- With whom has the e-sale contract been formed (legal capacity)?

- When and where was the e-sale contract formed?

- Are there legal uncertainties when determining the precise point in time that an e-sale contract has been formed?

- If an offer to enter into an e-sale contract specifically requires acceptance to be communicated in a certain form, whether an electronic communication of acceptance will be effective to form an enforceable contract?

- How can we identify the object and consideration in the e-sale contract?

Each of these issues will be discussed in the thesis relying on the general principles governing the formation and validity of the ordinary sale contract in Islamic law.

As such, the thesis presents an aspect of the ongoing research by Muslim scholars from around the world aiming to analyze the status of e-commerce in Islamic perspective. However, our thesis will be limited to and rely on Fiqh cases from the jurists in the four major Sunni Islamic schools (the Hanafi, the Maliki, the Shafi’i, and the Hanbali). These schools have greater common features between themselves, which frequently makes it easier and more correct to write our thesis, by way of generalization, on these schools.

The thesis will start in chapter 1 by familiarising readers with the background of Islamic law principles. The thesis shall initiate by putting forth an elaboration on Islamic law and shall proceed from this foundation onwards. This foundation is meant to serve as an outline and an highlighting of the specific relevance of this research and therefore it should not be considered to be anything along the lines of an extensive delving into Islamic Law. We will describe the main contract principles under Islamic law, to clarify the scope of this thesis. We will note the important basic features of the Islamic law regarding contracts, highlighting the way they facilitate the sale contract.

In chapter 2, the thesis discusses the validity of the e-sale contract from the Islamic point of view. At this stage, the initiation of the e-sale contract between both the parties begins through a check of the binding pillars of the contract. Offer and acceptance are the most commonly found constituting pillars in this regard along with the two contracting parties and the exact expression mode. The most important point that we will discuss at that initial stage is that these pillars in the e-sale contract must meet the Islamic requirements. Moreover, in this chapter, we will analyse the different kinds of contracts that can be classified as Islamic commercial contracts. It is imperative to note that these incorporate those that relate to ordered sale (bay’ al-Salam), manufacturing sale (bay’ al-Istisna) as well as Deferred Sale (bay’ Muajjal).

Chapter 3 will cover basic notions relating to the formation of e-sale contract under Islamic law, and is divided into four sections. The first section deals with basic features of psychological elements. The second section will treat the exteriorization of psychological elements, making reference to subjective and objective, or consensual isitc and formalistic, approaches in the Islamic law. The third section will review various means of expression, being word of mouth, writing, sign and conduct, and silence. The fourth section will examine the efficacy of these means of expression in the internet environment under Islamic law.

Chapters 4 and 5 will be the common analysis of an agreement in terms of offer and acceptance or, conversely, the treatment of offer and acceptance as the commonest mechanism for reaching an agreement. This entails a separate examination of various aspects of the mechanics of offer and acceptance in the formation of the e-sale contract, including their correspondence, and the nexus between the mechanism and the related agreement under the principle of Islamic law. Our discussion in these chapters first deals with offer, and second with acceptance (including its correspondence with the offer) and the import, or contents, of an e-sale contract comprising its terms and conditions and interpretation.

Finally, chapter 6 will be the conclusion of the thesis and its implications.

An Introduction to the Study of the E-Sale Contract Under Islamic Law

Islamic law (Shari’ah) is considered by Muslims to be the expression of the will of God, representing his final law governing men’s behaviour in this life and the hereafter. It is also regarded by some as an eternally valid and immutable standard of law. This is revealed in classical Islamic legal theory, which declares that no man has the right to interfere with Shari’ah or to change its rules. “It is comprehensive, universal, eternal, and not susceptible to change; its contents are set out in the authoritative codices of the orthodox schools.” Changes, therefore, can only be effected by the word of God through his revelation, to which men have had no access since the death of the Prophet Mohammed. Moreover, since God alone is the lawgiver, and the right of law-creation is possessed by him alone, it follows that man does not have the right to create law. Man’s involvement is thus confined solely to the application of Shari’ah.

However, some modern Muslim scholars have defined Shari’ah in an alternate way. They believe that this approach is no longer sufficient, and have thus resorted to a number of different methods to overcome this predicament. For example, Maududi distinguishes between the part of the Shari’ah which has a “permanent and unalterable character and is, as such, extremely beneficial for mankind, and that part which is flexible and has thus the potentialities of meeting the ever-increasing requirements of every time and age.” Another well known example is the opinion of Fazlur Rahman, who, although he defines the Shari’ah to include “all behaviour – spiritual, mental and physical”, also recognizes that the legislative provisions of the Qur’an have to take into account the attitudes and beliefs of the then existing society. This view, therefore, entails the acceptance by scholars that people do have the right to enact change to legislation, as long as it falls into the broad parameters of Islamic understanding.

Scholars of this new understanding of Shari’ah believe that law-creation, which is the right of God alone, should not be confused with the comprehension and discovery of God’s law. Therefore, they do not doubt that Shari’ah should develop and evolve continuously with the advancement of human beings’ thought and civilization. They believe that it is a gross mistake to assume that Shari’ah of the seventh century is still suitable, in all its details, for application in the twenty-first century. The perfection of Shari’ah lies in the fact that it is a living body, growing and developing along with the continuous progression of human beings, guiding their steps and directing their way towards God, stage by stage. Human life will continue on its way back to God inevitably.

Thus, in order to help the Shari’ah accommodate the ever-changing and ever-developing human beings, Muslim jurists devised Usul al-Fiqh. By doing so, the difference between the changeable and the constant and the reason for the classification of the same is brought forth along with any new debate that has to be subject to the Qur’an test which will be explained later in the chapter. In the event that a clear and undoubtable approval from the Qur’an is acquired, the change is integrated into Muslim society. Otherwise, it is tested for the Sunnah of the Prophet Mohammed (P.b.u.h). If there is not a clear sign of approval in the Sunnah, then the approval will then lie on the shoulders of other Islamic sources.

This chapter will therefore be divided into five parts, the first dealing with the classical structure of Islamic law, the second with the progressive concept of Shari’ah and Fiqh, including a study of Islamic jurisprudence, its methods of interpretation, the authority of the jurisprudential rules and the development of such jurisprudence. The third part of this chapter will examine the modernisation and possible future of Shari’ah. The future of Islamic law is discussed here, in light of its present authority and the ‘heated’ debates that occur in the contemporary Muslim world. The fourth part addresses the Islamic perspective of e-commerce, taking into account its legality, Islamic business ethics and e-commerce sale contracts. The fifth part deals with the general principles that apply to sale contracts.

The Classical Structure of Islamic law

The structure of Islamic law is rooted in the Qur’an and the teachings of Prophet Mohammed and the interpretations of these sources of revelation by his followers. Islamic law serves as a provider of the right Shari’ah and governs the relations between mankind and Allah. It would therefore be reasonable to consider it to be nothing less than divine law established by Allah and communicated through the Qur’an. Therefore, the sources are put at four: the Qur’an and the Sunnah, which are primary, and the Consensus (Ijma) (sources in common between Sunni and Shi’ah schools) and reasoning by analogy (Qiyas) for Sunni or ‘Reason’ for the Shi’ah, which are secondary. There are other sources of lesser importance which will govern the sale contract in the absence of any rule in the primary and secondary sources such as custom (urf), necessity (darura), and judicial contribution.

Since Islamic law is our main subject, a look at some of its general characteristics would show how it compares in this regard with other legal systems such as Common law and Roman law. The first point which deserves to be emphasized in my thesis is that Islamic law comprises two main divisions based on the relations between men and between humans and Allah. The first, the acts of worship (Ibadat), deals with purely religious matters (these include recitation of the ‘shahadah’, Prayers ‘salah’, Fasts ‘sawm’, Charities ‘zakat’, Pilgrimage to Mecca ‘hajj’), and the second, the transactions (al-mu’amalat), deals with all those subjects which comprise the only content of other legal systems, which include judicial matters, warfare, peace, drinks, punishments, penal, inheritance, marriage, divorce and financial transactions.

Primary Sources

The Qur’an and the Sunnah are considered to be primary sources in Islamic law. Also, in light of the consideration of the fact that their rules are penned down, they are also generically regarded as verses (Nusus) which may be translated as Script or Text, forming the written authority.

- The Qur’an

The Qur’an is considered to constitute the essence of Islamic law and is therefore regarded as the most significant the Holy Scripts of the Muslims. It is composed of 114 chapters; each chapter presents different verses and sheds light on numerous subjects. It is however imperative to note that the Qur’an does not address specific legal prescriptions. Approximately 80 of the 6000 verses that constitute the Quran pertain to law. The arrangement of the Qur’an in its present chapters and verses was made under the Third Caliph, Uthman.

The Qur’an contains, among such matters as historical narrations, fables, ritual observances, and what pertained to the Prophet’s life, specific principles that can be generalized along with numerous elaborative discussions on legal matters. These are scattered through various chapters and are far from being comprehensive. Some earlier verses were abrogated by later ones, while some others are in apparent contradiction with each other. All verses, however, have been retained and form part of the whole body. Broadly speaking, earlier verses handed down in Mecca, thus known as the Mecci verses, are more general in import, tolerant in spirit, and of an ethical nature. Those revealed later in Madinah, thus known as the Madani verses, are more detailed, and make up the majority of the legalistic rules, imposing specific commandments and abrogating certain (Mecci) precepts.

In the early period of Islam, the Qur’an as the Word of God was not open to comment. As time went by, as an outcome of the opposing views of different dogmatic segments across Islamic history, many commentaries, both Sunni and Shi’ah, have been produced which greatly help its understanding; but no matter how scholarly some may be, none is considered a binding authority.

- The Sunnah (Tradition)

While the Prophet (P.b.u.h) was living, he would answer the queries of his followers, adjudicate their disputes, and pronounce rulings which were considered, next to the commandments of the Qur’an, rules of law. The Sunnah is the performance, and methods of the Prophet Mohammed. In the start, following his death, a litigation would be dealt through reference to Qur’anic verses; in the event that none was found to provide a solution, the Sunnah was brought into use. The Sunnah constituted the tradition, speeches, and actions of the Prophet Mohammed (P.b.u.h). The Sunnah, therefore, appendages, illuminates, and elaborates the provisions of the Qur’an. However, it is significant to realize that even though the modus operandi of verification of authenticity and recording of Sunnah was undertaken by a large number of Muslim scholars of the second century of Islam, only the compilations of six scholars have come to be accepted by the majority of Muslims as containing sound of genuine Sunnah.

Thus, since then, the Sunnah has become a definite source of Islamic law. However, the Sunnah is still considered a supplementing source to and cannot be considered to supersede the Qur’an. In the event of such a contradiction, it is implied that the alleged Sunnah is weak or false.

however, based on the definition of Sunnah, it is indispensable to highlight the reasons why the Sunnah is multipurpose and therefore adaptable in a form such that it can handle present day problems and issues coming forth as a result of the increasing intricacy of life. In a modern day community, a moral tension exists in the form of a range of legal as well as administrative intricate problems. The theological and moral dimensions of expanding Islamic society have given way to numerous controversies. Even though new material was considered and incorporated, the ideal Sunnah was kept intact as a consideration source. This particular process of interpretation began with the comrades of the Prophet explicitly as well as tactically resulting in the deducing of numerous norms with practical applications in modern day society while keeping the rules of the Qur’an in performance.

Secondary Sources

The reason behind Shari’ah as a system that is a religious and legal brings it to a point where there is no doubt left that it is to be inferred from no source other than the Qur’an; second from the Sunnah. In case the primary sources (the Qur’an and Sunnah) are silent on the issue, then the consensus (Ijma) and reasoning by analogy (Qiyas) will follow as a source of Shari’ah according to the four Sunni schools.

- Consensus (Ijma)

In the event that the Sunnah does not provide the required level of clarity in guidance with regard to the subject issue, the third source for Islamic Law is present in the form of Ijma. It is a combined agreement across Islamic scholars of a particular age group regarding the rule of law that is most appropriate to the issue. It is imperative to note that the Ijma is a an inference derived from independent legal reasoning on areas where the Ijma has to be resorted to. It is only permitted in areas where the Qur’an and the Sunnah provide no definitive instructions. The jurists represent the Muslim community in this regard and seek to reach agreements on issues. Once an agreement is reached, the resolution to the issue becomes integrated into Islamic jurisprudence.

The Ijma comes into action only in cases where there is no directly or indirectly applicable testament in the Qur’an and the Sunnah but it is important to note that it should not under any condition contradict them.

Ijma was found in its most profound form in the beginnings of Islamic law during times when the community used to be of a form such that it would be fairly small and very few eminent jurists existed. This allowed the views of all the jurists to be acquired.

- Reasoning by Analogy (Qiyas)

In the event that the Ijma also does not serve as an adequate Muslim judge, the Qiyas is referred to. It is only resorted to in the case when no legal authority on an issue exists and in this case, the ruling of the Qiyas is generally based on an accepted principle and is considered to be “from the explicitly known to the explicitly unknown” would fit such a particular rule in relation to an issue at hand.

Principles of reason, effectively used for practical purposes as logical devices for the inference of detailed rules out of primary sources and the Qiyas, which are placed last in the formal hierarchy of conventional sources, have in fact made a contribution, at least in all Islamic schools, no less impressive than the other sources. Muslim jurists’ views and opinions expressed and employed in numerous expositions and commentaries under each school or trend have also contributed to contracts in Islamic law.

Other Informal Sources

The other sources of Islamic law consist of:

- custom, which has through the ages influenced the development of the detailed rules of Islamic law;

- compendia, commentaries and religious rulings which, according to all Islamic schools, have shaped, supplemented or influenced the respective law;

- reconsidered thoughts and writings from Muslim scholars in the late nineteenth century onwards, which put a fresh interpretation on the age-old rules of Islamic law to bring them into line with modern needs, and subsequent legislative formulation in certain areas of Islamic law in the respective Muslim countries.

Progressive Concept of Shari’ah and Fiqh

A part of Shari’ah more concerned with the actual behaviour of man in this world is termed Fiqh which consists of detailed rules and is closer than Shari’ah to the concept of law, though often the two original terms are used as synonyms. Fiqh, in spite of having a narrower ambit than Shari’ah, covers a much broader area than law by including such rules as those on purely religious observance. A substantial part of Fiqh, however, correlates to the present-day notion of law.

For convenience, Shari’ah or Fiqh is often rendered in English by the term ‘law’ and sometimes by the term ‘jurisprudence’ , though the latter is apt to generate confusion because of its particular use in English for a branch of jural study on the theoretical basis and philosophical aspects of the law.

Faqih (sing: Fuqaha) is a scholar who is versed in Fiqh and, being religious, is required to be pious and observant. He is a religious jurist, sometimes referred to in the Western literature as a ‘jurisconsult’. In the following research, we shall generally employ ‘law’ for Fiqh, which itself is a part of Shari’ah and not infrequently equated with it, and shall utilize ‘ religious jurist’, or simply ‘jurist’, for a Fuqaha.

Another clarification to be made concerns the concepts of ‘school’. Islamic law is not a uniform or unitary system. It consists of subsystems according to various schools. A ‘school’ refers to a particular Islamic faith and the related subsystem of law, each a system in itself, and not to a trend of jurisprudential doctrine or thought.

There are five major Islamic schools today of which four are Sunni and the fifth is the Shi’ah, itself divided into several branches of which the most important is the Twelve (Ithna Ashari). Depending on the level of comparison, these schools present differences which distinguish them from each other and similarities which bring them together. There are notable differences in methodology and detailed rules between these schools. Our reference to the particularity of Sunni law in this research is exclusively to the four Sunni schools, Hanafi, Maliki, Shafi’i and Hanbali.

It may, therefore, be said, as a first categorization, that there are Sunni schools and Shi’ah schools, albeit that each are divided into individual branches. In a broader context, all the schools, whether Sunni or Shi’ah, have a common core in history, sources, classification, methodology, and so on, which makes it possible (notwithstanding variations and disunity in details) to treat Islamic law as a comprehensive system on its own, distilled from the general features of its various schools and branches.

All the four Sunni schools developed from the beginning of the second/eighth century. They were founded by, and respectively named after, pious and learned men, each referred to as ‘Imam’. These schools are the Hanafi, founded by Imam Nu’man Abu Hanifh (d.150/767); the Maliki, founded by Imam Malik ibn Anas (d. 180/796); the Shafi’i, founded by Imam Mohammed ibn Adris al-Shafi’i (d. 204/820); and, the Hanbali, founded by Imam Ahmad bin Mohammed bin Hanbal (d. 240/855). Each, particularly the Hanafi school, was subsequently further developed by the respective disciples of the founding Imams who were themselves eminent jurists in their own right.

The Traditionalist and the Rationalist schools of thought are two schools that have come forth as a result of the evolution of Islamic law through these two approaches. These are associated with their respective differing views on the law sources. However, considering Qur’an as the empirical source, the former trend tends to restrict itself to Traditions (Sunnah), the words and deeds narrated from the Prophet Mohammed (P.b.u.h) as a source of the law, while Rational Principles (Aqli) are supplemented with the latter trend. The paragraphs to follow shall shed more light on the subject of the sources of these elements.

Of the four Sunni schools, the first two (Hanafi and Maliki) developed almost concurrently, and the third came about just after the first two and partly overlapped in time with the fourth. The Hanafi school, adopting a Rationalist approach, allowed the greatest latitude for ‘free reasoning’ (ra’y), while the Maliki school was Traditionalist. The Shafi’i school was ecletic, trying to reconcile the first two, for which reason its founder was accused of being a Traditionalist by the Rationalists and of being a Rationalist by the Traditionalists. He was in fact both, but predominantly a Rationalist. He placed greater stress on Traditions than did the Hanafi but organized, for the first time, a set of Rational Principles (Usul al-Aqli’ah) for the inference of detailed rules out of primary sources which brought order to, and restrictions on, the application of reason. These principles were in due course further refined and developed into a separate Islamic methodological discipline called the Science of Principles, or Roots, of the law (Ilm Usul al-Fiqh). The Hanbali School instituted a vigorous reversion to Traditionalism which was much later revived with a puritan austerity by the Wahhabi movement in the twelfth/eighteenth century, originated in Arabia by Mohammed ibn Abd al-Wahhab. Since the establishment of Saudi Arabia in 1926, the Hanbali faith has been revived and has been made the official school of Saudi Arabia.

The respective context of the development of these schools, together with their pairing off according to the said two tendencies, is significant. The Maliki and Hanbali, both Traditionalists in approach though different in degree, developed in Madinah, the city of the Prophet Mohammed (P.b.u.h) which is located in Saudi Arabia, which after his death gradually lost its economic and political importance. Both schools, and their conservative approach, are therefore referred to as Madani, ‘of Madinah’. The Hanafi and Shafi’i developed in Iraq (the latter also partly in Egypt) which became at the time the economic and political centre of the Muslim world.

It was until the four schools had been formed that a general conviction developed among the society. It was believed that the gates of Ijtihad had been closed. Ijtihad referred to juristic reasoning whose rules and procedures were not founded on the primary sources. This process took place during the latter half of the 3rd to the 9th Century. Consequently, the generations that followed had to adhere to the teachings from the four established schools who were considered the masters of the art. As a result, the Sunni law faced a long period of stagnation. The status quo remained so until later in the 19th C. During this period of stagnation, many jurists worked within the specifications of the four master schools. They elaborated on the developed rules but rarely made any original contribution.

Some scholarly analysis from Western writers have attributed this stagnation period which led to the practitioners abandoning the Ijtihad to the aspect of uncertainty that engulfed the Islamic world after the Tartar invasion. Among the writers who have tried to elaborate the situation are Gibb and Schacht. In addition to the Tartar invasion, the uncertainty was also caused by the Mongols who had sacked Baghdad in the year 1258. These two events profoundly affected the Muslim scholars converting them into conservatism. They offered no room for innovation in matters that concerned religion. As a result, the Shari’ah was cast into iron frames that would not offer any form of flexibility and hence could not reflect the changes that were taking place with modernity. This greatly led to its decline.

In fact, the conservative ideas persist to this age. Some quarters of the Islamic world still argue that the interpretations of Shari’ah made during and prior to the 11th Century should be altered and thus no variations. They still argue that any nouvelle development is inaccurate because the interpretations during the mentioned period are the only correct interpretations. This has led to formation of factions and movements that hold on to the idea that the Muslim world should revert to the original teachings and thus live a life similar to the Islamic “golden age” where definition of life was mostly framed based on the events during the prophets lifetime. Interestingly, the faction leaders tend to choose certain aspects of the society to impose restrictions while ignoring other aspects that have equal relevance. For instance, they impose restrictions on women, satellite dish installations and other medieval restrictions while using super vehicles and up-to-date weapons of war, which do not reflect those, used during the prophet’s time. In those days, camels were used as the most common means of transport while bows and arrows were the weapons of war

The 16th and 20th Centuries marked an era of European expansion. At this point in time, the European colonisation powers traversed the planet subjecting several countries under their commercial and political dominion. The Muslim countries were not an exception. They were also forced to operate under the European dominion. For instance, India and Malaysia were under the British dominion. On their part, the Middle East experienced certain political mandates from the British too. Indonesia tested the colonial dominion of the Dutch while the French ruled a larger part of North Africa. The French dominion was also experience din some parts of the Middle East after the Ottoman Empire hit a stag.

In the countries where mixed legal system was practised, there were instances where the Shari’ah legal system was completely replaced by the Western style legal system. However, the colonizers did not put emphasis on the aspects of the law that was of less value to them. As a result, the countries maintained their Shari’ah law system on the aspects of family law and inheritance, but there were great changes in areas that could impact the colonizers. The influence of the Western system legal system was felt beyond the colonial territories. For instance, regions like the Ottoman Empire were influenced by the western style legal system despite the fact tat they were not colonized by any Western power. Consequently, Ottoman Empire resorted to the system in its quest to modernize. During the 20th century, there were differences in the countries’ adherence to the Shari’ah law. For instance, Turkey had completely done away with Shari’ah law and embraced Kemal Ataturk while on the opposite side Saudi Arabia had adhered to Shari’ah law almost word by word.

Many thinkers in the realms of Islam and the major schools in the Islamic jurisdiction never accepted the fact that Ijtihad had been closed, such as Ibn Taymiyah in the 14th century, Fazlur Rahman (d.1988), Mohammed Iqbal in Pakistan (d.1938), Hasan al-Bana (d.1949) and Mohammed Abduh in Egypt (d.1905), insistently argued that the Islamic Ijtihad had continued to exist despite the strong influence from Western civilization. To them, qualification in Islam was what would have allowed one to interpret the laws. However, the four schools did not put any form of restraint to Muslim integration of the law. Qualified Muslims could interpret the law without any problem. As their uultimate objective, they intended to develop a new fiqh that would enable the laws to revflect modernization in the nation state that was emerging. Some contemporary writers including Abdullahi an-Na’im accept this argument.

According to Bannerman, modern Islamic thought is made up of four integral parts which are:.

- Orthodox conservatives whose fundamental beliefs are centred on taqlid;

- Quasi-orthodox conservatives, whose beliefs relate closely to the above but they acknowledge the presence of western influence to their beliefs,

- Modernising reformers, who believe that the fundamentals of Islam must be withheld but be incorporated with the ever changing environment; and

- Conservative reformers, who believe that taqlid is wrong and at the same time propose certain limits to ijtihad.

Modernisation and the Future of Shari’ah

Several hardships and forms of injustices was witnessed in the Muslim laws as most of the countries devoted their efforts to modernise their legal systems to reflect the contemporary challenges and other changes within the society. A good example was the Hanafi rule, which prevented women in India and Ottoman Empire to go for a devorce without thet consent of the husband. As a result, a solution to this problem was imperative for any success. Modern Islamists who were determined to promote the siyasa Shariah doctrine hence developed Takhayyur and talfiq.

Takhayyur was a term that meant inclining to an opinion given by the ancient jurists. However, if one school did not satisfactorily give a solution to a given problem, a solution could be sought from other prominent schools. These allegations were supported by the doctrine of Talfiq, whose fundamental argument is building a substantial Islamic legal rule through a combination of specifications from different schools join order to get solutions for several problems.

Scholars from the Muslim rights have insistently fought for the rights to freed from the stiff taqlid specifications and to be given power to Ijtihad and hence interpret the Quran and the Sunnah and come up with a new legal system which would reflect the contemporary challenges. According to them, a journey back to the sources would allow them to identify whether there were other options that would be used to interpret the laws in their originality. For instance, a Muslim man could marry as many as four wives at ago. This is according to the holy Quran. However, modernists argue that it is very difficult to attain the fairness and justice specifications in order to qualify to marry the four wives. To them, this is a prohibition of polygamy. Immediately after the verse that allows polygamy, the Quran reads;

“You will never be able to be fair and just between women even if it is your ardent desire”

Since fairness and justice are impossible, a man must therefore restrict himself to one wife.

As a result, the verse has witnessed different opinions as most people keep interpreting it in terms of their inclined opinions. Equally, the law witnessed similar differences in interpretations. A good example of this is the aspect of music and art in the Islamic religion. Some Islamic countries strongly hold on the argument that music is Haram (unacceptable). Those who hold on to this tenet draw their beliefs from certain hadiths that are against “vain talk.” The favourable form of entertainment for a believer according to these hadith’s is archery and horse breaking. In addition, drawing, painting and sculpture are form of image creations. These, according to Quranic teachings are the pathways to idolatry. The Taliban in Afghanistan put a devout belief in this teaching in practice and other groups like the extremist Muftis in Saudi Arabia, who had resorted to ban music in their respective countries, television, put all audio and video tapes to destruction, and banning photography. To them, this was going against God’s law and could lead to idolatry.

On the other side, those who ardently oppose this view argue that the Quran dictates that all things that are not expressly forbidden could be permissible and hence emphasising on these ahadith is misinformation. Their argument is further strengthened by other ahadiths that highlight the importance of music as a form of entertainment as specified by the Prophet in Ansar. According to the Prophet, the music cannot be termed bad provided the lyrics are not un-Islamic and that the singers and performers do not lead one into temptation. In other beliefs, sculpture is the only forbidden form of art. As a result, calligraphy and geometric design form the main form of art that is acceptable.

With the world facing new changes in terms of technology and economy, it was imperative that the old rules are changed to reflect these changes.

Diversity in opinions can result into proper decision making. Consequently, religious scholars need support from other scholar in order to improve on their opinions. Therefore, collective ijtihad is the proper way of interpreting Shariah laws. Collectivity here involves participation in ijtihad by both the religious and non religious scholars so that each one gives his opinions in relation to his field of specialty. Encouragingly, several Islamic countries and other countries in Europe already have such councils working together. A good example is the “European Council for Fatwa and Research” which was formed with its headquarters in London in March 1997.

The new Ijtihad has come up with legislations like the one concerned with infertile couples. According to them, such couples should accept the fact that they are not capable of getting a baby and hence live that way or make the decision of adopting one. Furthermore, teh couple should as well resort to sperm or egg donation as they make use of the developed technology. These options pointed out the need for new ijtihad as classical theorists never came to realize of such developments during their time. In fact, such things did not get any mention in the Quran nor the Sunnah. They therefore called for new solutions for new problems that did not exist before and hence had not been mentioned earlier by the scholars of those eras.

Despite the controversial nature of law interpretation, most of the scholars have come up with a single point of understanding. They believe that a family, as an institution plays an important role in promotion of the religion. As a result, all parents have the right to seer children of their own. The means by which they can achieve this obligation cannot be incriminated. Therefore, they can use technology provided they afford it. However, if the sperm used does not come from the spouse i.e. comes from a different donor, this will be a violation of the Islamic law and hence not acceptable. Equally, surrogate motherhood is unacceptable because it makes use of an individual outside the family unit.

Financial realms bring out another application of contemporary ijtihad. In the original teachings of the Quran, a Muslim should avoid associating himself with interests. Precisely, he should neither give nor take interest. This clearly means that no commercial transactions should be carried out in non Muslim commercial banks as this will subject the Muslim to giving or taking of interest. They are not allowed to invest their money in such banks. This marked a major hurdle in the investment decisions of many Muslims. As a result, Islamic banking was formed in order to bridge the gap.

Among the many modernist-reformist voices that have proposed to bridge the gap between the Qur’an’s extrahistorical, transcendental value system of equal rights and its actual application in Muslim legal tradition riddled with discriminatory practices is the Sudanese jurist Abdullahi An-Na’im, disciple of Shaykh Mahmoud Mohammed Taha (d.1985), founder of the Sudanese Republican Brothers movement. Taha’s approach to the problem, as outlined in his book, had been to differentiate between the Qur’an early (Meccan) message (tolerant and egalitarian) and its later (Medinan) message (seen at least in part as an adaptation to the socioeconomic and political situation of the Prophet’s Medinan community). An-Na’im has since developed his mentor’s general principles into a framework for the radical reform of Islamic law and legal institutions that invalidates the established historical institution of ijtihad in favour of a new “evolutionary principle” of Quranic interpretation; which reverses the historical process of Shari’ah positive law formation (which was based on the Qur’an’s Medinan verses) by elaborating a new Shari’ah law (based on the Meccan revelations). This modernist approach, which reflects a sort of revival of the beliefs of the early Muslim jurists in the close relationship between law and culture in Islam, denies all normative powers to the Shari’ah as presently formulated but maintains the essential validity of the concept.

The problem regarding the position and ongoing normative powers of the Shari’ah in contemporary Islamic societies has continued to exacerbate polarization between secularist and traditionalist points of view. Secularists have argued that the Shari’ah has lost its normative power and is no longer applicable. They have argued that the Shari’ah laws relating to business and economy are outdated; other laws, such as those regarding slavery, are no longer valid, and the remainder “is largely contrary to international human rights and individual liberty laws.” In diametrically opposed fashion, Islamists are likewise focused on the normative power of the Shari’ah (as presently constituted) by upholding it in essentialist terms. This means that when the law and social practices diverge, it is the law that is valid and social practice that must change in order to achieve conformity with it. The less society conforms to God’s law, the more urgent is the Islamists’ demand for change and purification. As exemplified by Sayyid Qutb (d. 1966), chief ideologue of the Muslim Brother in Nasser’s Egypt, Islamism has defined sovereignty largely within a framework of law and authority where the sovereignty of God is synonymous with the sovereignty of the Shari’ah within an Islamic state. When Islamists, therefore, call for a “return of the Shari’ah” they do not mean to bring back the traditionalist fiqh (tainted by centuries of ulama-state accommodation), such as the Taliban regime has done in Afghanistan; rather, they envisage an alternative Shari’ah based on the Qur’an and, especially, the restoration of the Prophet’s Sunnah that prominently involves the building of a new state structure and new political institutions under Islamist leadership.

By contrast, when the traditionalists, especially now given a voice by conservative clergy and legal experts, call to restore the Shari’ah, their demand is generally for the restoration of Islamic fiqh to replace the legal norms and institutions that were created during the colonial period or by the post-colonialist nation-states. So far, only a few of the establishment’s religious scholars have used their professional credentials and legalistic expertise to develop innovative opinions within the legal methods of traditional fiqh. A prominent example is Yusuf al-Qaradawi, who arrived at new formulations of Muslim women’s social and political rights during the 1990s by way of the established fiqh: indigenous methods of law finding. In addition, the general public has to some degree begun to participate in the civilizational debate on the role and meaning of Islamic law in their modernizing societies. By way of the new media, especially the new electronic means of communication, non-specialist Muslim individuals, including women and the young, are beginning to create what may perhaps one day turn out to be a groundswell of scripture-based individual opinions on legal issues that they derive largely from a personal study of the Qur’an.

Is the Shari’ah as a legal system now defunct? While there is a clamor by Islamists in the Islamic world for the restitution of the Shari’ah and an affirmation of its efficacy and eternal validity, Wael Hallaq, in his opinion, argues that the Shari’ah is “no longer a tenable reality, that is has met its demise nearly a century ago, and that this sort of discourse is lodging itself in an irredeemable state of denial.” Although sympathetic to the desire of the Middle East to distinguish itself from the West, Hallaq is firm in his assertion that the concept of nationalism and the creation of modern nation-states have negated the possibility of living by any comprehensive system of Shari’ah. He supports his opinion by analysing the nature of reforms currently under way that he refers to as the “cobbling together” of interpretations of Shari’ah borrowed from various historical legal schools and other legal-theological traditions. Spurred on by international pressure to create a body of laws that will adhere to the conditions of a modern constitution, lawmakers in the various nation-states are now creating hastily constructed legal templates that will satisfy both international organizations and popular ideologies. The only way to achieve such a precarious balance is to adopt the most lenient laws offered by the various inherited legal traditions, laws that will receive the support of the population. The only sector of law maintaining any uniformity under these conditions, Hallaq argues, is personal status law. it may, however, be precisely the latter’s more Islamic uniformity, as opposed to the heterogeneity of the rest of state law, that will eventually serve to accentuate the larger legal system’s incoherence and thus contribute to strain “the intricate connection between the social fabric and the law as a system of conflict resolution and social control.” The root of the problem, according to Hallaq, is the modern state control of waqf (the wealth amassed by centuries of private unalienable property contributions formerly administered by representatives of the clerical establishment), the loss of which has undermined the ability of Islamic schools of law, institutions, and officials to function independently of the political establishment and thus has destroyed their tradition of legal innovation and adjustment that informed the formulation and practice of Islamic law in the past.

We agree with the argument of Islamic modernists such as Fazlur Rahman, Abdullahi An-Na’im, Mohammed Iqbal and Abdullah Saeed117 who argue that contemporary challenges must be incorporated whenever the ethico-legal interpretation of the primary Islamic sources is done.. this will assist the analysts to come up with solutions to problems that would have otherwise not been mentioned in the original interpretations done during classical eras. The philological nature of Quranic interpretations must today focus on the sociological and philanthropic aspects in order to come up with interpretations that reflect the contemporary challenges facing Muslims. However, as much as the sociological and anthropological aspects have to be incorporated, it is imperative that the classical exegetical traditions are adhered to. They should act as the guidelines by which contemporary analysts can use to come up with proper interpretations. However, the sections that seem not applicable in the contemporary society should be done away with. That understanding can be helpful in our formulation of new interpretations in the light of new circumstances and challenges.

Challenges and Opportunities of Business and E-Commerce under Islamic law

The internet offers great opportunities that can be used in the world today. For instance, through the internet, people can gather information and also buy stuff without having to travel the many miles between the buyer and the seller. Culture from other regions of the world can be learned through the internet. Through this Internet, products can be sent to customers. All these can simply be explained as the e-era. This is an era where e-commerce has been taken to be the bedrock of economic development. However, this form of trade has been made by challenges in the Islamic world. This part intends to highlight the challenges and the formulation e-commerce that reflects Islamic teachings.

The world commerce industry, the way we communicate and do business has changed as a result of the impact of the internet. As we can see the changes are taking place rapidly in our daily life. We do not have to personally go to the hardware and supplies shops to buy materials required for building a house. What you have to do is to switch on your computer with an internet connection. While connected to the internet you are able to browse the online supermarkets and click on every single item that you want for the house construction in your virtual shopping cart. In a few days all the items ordered through the internet will be delivered to your doorstep. What you must have is a debit/credit card number and a postal address.

Islamic business can be established as an amalgamation of business organizations that function under the guidelines of the Shari’ah and do not engage in any of the following activities.

- Operations involving Riba or Interest as it is commonly referred to as.

- Maisir or Gambling involving operations.

- Operations involving the manufacturing of non-halal products such as Pork or liquor.

- Operations involving Gharar or elements of uncertainty such as those found in modern day insurance banking.

According to Yusuf al-Qaradawi (a modern Muslim scholar from Egypt), there is no prohibition of trade in Islam in any circumstances other than those that involves the promotion or encouragement of cheating, exorbitant profiting or the engagement in activities that are classified as haram.

The goal of Islamic business will be two fold: maximizing the profit margin while ensuring social welfare maximization alongside.

Not only are trade activities the major economic activities at present, they are also the main economic activities of our ancestors. The traditional way of doing trade however is changing rapidly with the introduction of the internet. Physically, the internet is nothing more than an unregulated network of computers mostly linked either by telephone lines or broadband connections. It is different from our traditional way of doing business or trade. The internet development is so rapid, that no business, conventional or Islamic, could afford to be left out in order to be able to compete in the free market.

Therefore Islamic business must take part in the internet development to be at par with all other business. However, studies need to be conducted in the E-commerce area to adjust Islamic business needs in order to ensure that they are in line with Shari’ah guidelines.

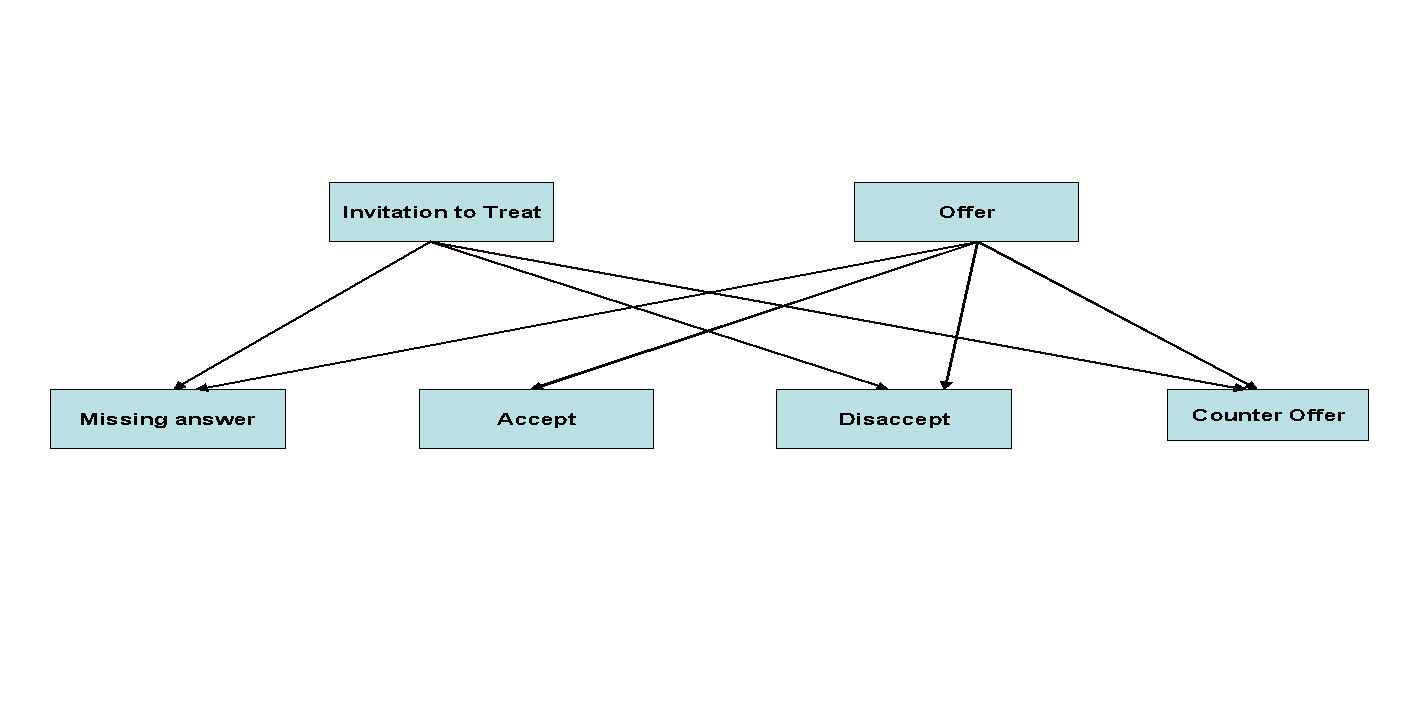

Three rules of thumb are to be followed when dealing in Islamic e-commerce dealings, first is the offer made, second the acceptance of the offer and thirdly the consideration of this offer. Once these have been met the contract is not against any of the Shari’ah guidelines which consult from the Ibahah. The law assumes that all things are acceptable if specific Qur’anic injunctions are not used.

The notion is that if something is not directly stated to be wrong then it is not according to the maxim “lawfulness is a recognized principle in all things.”

Business done in the perspective held by Islamic people is downhill since sellers and buyers are protected if adhering to their principles. The only difficulty can come in if one tries to avoid the riba/gharar, it is next to impossibility. This is because nearly all deals made will involve them whether directly or in another way. Maisir which is another law,and selling illegal products are also to be adhered to. All the laws should be considered even when profit maximisation and success are key.

Most Muslim business people ignore the Gharar law and the Riba. The latter is interest or gain from lending out. The conventional financial structure benefits from this.an Islamic business would face problems if it does not uphold this because it is like not following the Islamic principles.

Riba is clearly prohibited from the Qur’anic perspective:

“Those who devour usury will not stand except as stand one whom the evil one by his touch hath driven to madness. That is because they say: ‘Trade is like usury,’ but Allah hath permitted trade and forbidden usury. Those who after receiving direction from their Lord, desist, shall be pardoned for the past; their case is for Allah (to judge); but those who repeat (The offence) are companions of the fire: they will abide therein (for ever)”

The only solution to the problem of obeying Riba would be in having banking systems that are Shar’iah compliant this is in operation in most modern banks.

Muslim business people just starting business should not be involved in Riba in the financial processes when selling online. To avoid, it they should engage in Islamic banking which covers all the processes in adherence to the law. Some of the products covered are Mudarabah, Musyarakah and Murabah. The change is universal and cannot be avoided.

Islamic banks have provided Muslims with the advantage to use commonly used systems that are not Shariah compliant. The systems in these banks have to be compliant and abide by the laws even for e-commerce.

The other challenge has been the gharar elements especially in the area of trading contracts. Many hadiths have been identified on the same issue, most of them specific in terms of scenario. A commonly cited hadith is that quoted by Imam Ahmad, Imam Muslim, al-Tirmidhi, Abu Dawud, Ibn Majah and al-Nasa’i, all of whom do so upon the authority of Abu Hurayra that:

“The Prophet (P.b.u.h) prohibited the gharar sale”.

The Shari’ah established that in order to ensure fair dealings between parties in contracts, any case in which an uncertainty leads to an unjustified enrichment in contract is prohibited According to Kazi Mortuza Ali in his paper “Introduction to Islamic Insurance”, gharar can be found in all the business dealings in which a party involved in the contract has no perception or idea about what the party shall receive upon the conclusion of the bargain. Yusuf al-Qaradawi defines gharar as an action in which something is sold with clear incorporation of uncertainty and can be expected to lead to the generation of conflict or an unjustified enrichment.

If gharar is to be avoided, the parties must ensure that:

- the prices along with the subject of the sale are in existence and can be delivered,

- the specific characteristics of the items and the counter value can be established,

- attributes that are fundamental such as quality, quantity and delivery date are predetermined.

If any of these prohibitions, riba and gharar, can be avoided along with other prohibitions, the Islamic business can achieve the two goals of profit and falah (success) maximization.

E-commerce does have a place in Islamic perspective; however, whenever it takes place, certain requirements of the Shari’ah should be complied with and adhered to. This is to ensure that the goals of the Islamic business, which are falah and profit maximization, could be achieved. By achieving these goals the Muslim can be successful in business and also in the days of hereafter. Falah maximization could be achieved by abiding by the Shari’ah and the four major prohibitions outlined are the prohibition of riba, maisir, gharar, and of selling prohibited products such as pork. On the other hand, profit maximization of the Islamic e-commerce could be achieved by differentiating products, fair price, quality and services offered to the customers through e-marking mix and networking. In adhering to Islamic principles, the Islamic business must have the products, full information or description about the products and the ability to deliver the products. As far as e-commerce is concerned, it is permissible in Islamic perspective as long as it abides by the Shari’ah guidelines. The Prophet (P.b.u.h), through his sayings and action, encouraged the form of trade that considers merchants to engage in honest trade so that they may be considered with Martyrs on the Day of Resurrection.

The Islamic Sale Contract

In the absence of a general theory of contract in Islamic law, the study of the e-sale contract should lead us first to begin with several observations and a deeper understanding about the traditional sale contract in general, and then consider the e-sale contract in particular. It is imperative to note that Qur’an and the Sunnah , in their dictation of Islamic law, present general rules pertaining to the law of contract which are unique when compared to the laws of individual contracts. In the Qur’an, there exist well over forty verses pertaining to a dozen forms of commercial contracts. Aside from the specific verse on performing contract, Qur’an 5:1, and the three on the necessity of keeping a promise, a few other verses also shed light on advanced commercial contracts dealing with selling and hiring.

The Prophet Mohammed (P.b.u.h) himself was a merchant and engaged in commercial practice, however, he forbade some and permitted other activities in commercial practice. Most of these guidelines can also be found in the Qur’an and can therefore be considered to be nothing less than Divine Commands that are to be applied at all times. Other guidelines can be found in the Sunnah as well as in authenticated references dating back to the actions and words of the Prophet.

However, the Muslim jurists from the four Islamic Sunni schools have devoted by far the greatest part of their scholarly writing to specific contracts such as the sale contract. Businesses in the Islamic law are faced with the same set of financial challenges.

By confidence in the Qur’an and the traditions of Prophet Mohammed and all supplementary imperative alternates, the Islamic law will be wide enough to accommodate the needs of e-sale contract requirements, without however going against the general principles of Islam.

Prior to discussing the formation of the e-sale contract under Islamic law, it is essential to deal, in this chapter, with the general fundamental rules and principles governing the traditional sale contract. It is hoped that an exposition of these general principles and rules will assist in the clarification of the more detailed discussion on the formation of the e-sale contract under Islamic law which will follow later.

In Islamic law, there are various definitions of contract in general, and the sale contract in particular. The contract word in Arabic (Uqud) covers the entire field of obligations, including those that are social (like marriage), political, and commercial, and also deals with the individual’s obligation to God (Allah). However, the most well-known definition of the sale contract in particular came in the initial contemporary establishment of an Islamic law of obligations and contracts, Mejella al-Ahkam al-Adliyyeh article 103: “contract is an obligation between two persons or contractors about a lawful act in good manner” or “exchange of offer and acceptance with real intention”.

However, if the contributions made by the jurists of different Islamic schools of thought were considered, it is observed that differing definitions of a sale contract and it is dealt with much more widely in fiqh writings than other contracts. A sale contract for Abu Bakr al-Kasani, the Hanafi author of Badaa’i al-Sanaya (d. 587/1191), purports the exchange of a coveted article against another coveted article; such an exchange takes place either by words or by deed. For al-Kassani the binding effect of the sale contract and the conferring of immediate possession of the countervalues intended to be exchanged are its two main effects. Muwaffaq al-Din Ibn Qudama, the Hanbali author (d. 620/1223), sees a sale contract as an exchange of property against another property conferring and procuring possession.

As we look at these early definitions, any definition suffers from an inherent inadequacy. Linguistically, words have different shades of meaning. Technically, terms and expressions evolve and frequently change over the course of time, albeit imperceptibly. Therefore, we find any definition involves a high degree of abstraction which, when applied to the instances meant to be covered by it, may fail to achieve its intended ambit. At best, a definition may be considered as a proposition for the explanation of the scope, or an initiation to the exposition, of the subject concerned. This approach to definition of the sale contract is perhaps more suitable to a jurisprudential treatment of the subject than to a normative formulation of it.

As a result, we may prefer to define the sale contract the way some authors define it, as the relocation of possession of legal goods for a set price (money or other assets), with both standards established and conveyed without delay. However, impediment in imbursement of a counter-value is considered as a unique case in Islamic law. The title of both countervalues transfers immediately at the time of sale, even if actual payment or delivery of property is delayed by stipulation or otherwise.

In the Islamic legal system, like other legal systems of the world, certain formalities and substantive elements are essential for juristic acts to become legally binding on the parties. Classical Muslim jurists developed a clear concept of juristic acts which produced a legal effect on all commercial contracts. The sale contractual transactions, whether written, unwritten or by correspondence, constitute the vast majority of juristic acts. That being so, Muslim jurists of the four Islamic schools stipulated a clearly defined idea of the conditions and requirements of validity for a binding sale contract. These essential conditions and requirements of substantive and procedural law now provide the criteria for void, valid, binding and enforceable elements of all contracts in general and the sale contract in particular. Muslim jurists from these schools laid down a set of criteria for distinguishing between essential conditions on which the valid conclusion of the sale contract depended, and those which are regarded as less fundamental and which might affect its binding force on only one of the parties in the sale contract. Furthermore, Muslim jurists went further and spoke of non-existence of goods in the sale contract as a radical form of nullity under which the contract was considered as if it had never taken place. They also recognised, in contrast to the above category, contracts the effects of which were merely suspended (mawquf ala al-ijazat), depending on the choice of the party whose intention was not validly expressed, and for whose protection the nullity was prescribed.

Principle of Freedom in the Sale contract

Islamic scholars from different schools seem to differ in their opinions regarding the degree of freedom contractors have to conclude a contract. However, a closer examination of their opinions reveals that they agree on the major rules and principles relating to the freedom of contracts and they only differ on some details. The first view, which is the view of the Hanbalies and Malikies, explains that contractors are totally free to conclude whatever they wish, provided that it complies with Islamic rules and principles. This view believes that the root principle of contracts in Islamic law is the freedom of contracts except where they are explicitly prohibited by a provision or an injunction. Proponents of this view base their argument on some provisions from the Qur’an, and Sunnah and reasoning. Of particular importance here is:

“O ye who believe, fulfil pledges….”

“… but Allah hath permitted trade and forbidden usury.”

“O ye who believe! Eat not up your property among yourselves; but let it be amongst you traffic and trade ….”

“How can men stipulate conditions that are not in the book of Allah? All conditions that are not in the book of Allah are invalid, be it a hundred conditions. Allah’s book is more trustworthy and his conditions is more worthy to obey.”

The second view is that of the Hanafies and the Shafi’ies, which have established a middle course concerning the issue of freedom of contracts. Their handling of the subject of freedom to include conditions in contracts shows, as will be seen later, that they are, in principle, not as liberal as the Malikies or the Hanbalies.

Regarding the conditions which can be included in sale contracts, jurists categorise the conditions that can be valid and legally sound as follows:

The Stipulation Inherent in the Nature of the Sale Contract

Questions have been raised as to how valid an E-contract is especially baring in mind the Islamic school rules. There have been changes on terms of contract and these changes have actually helped modernize business and worldwide acceptance of internet transactions. The progressions of computer, telecommunication and information have certainly brought change to commerce world. There has been integration electronic operation worldwide. Electronic trading entails selling and buying of products, service and information by means of computer network (internet). By E-commerce we imply at least two entities transacting via internet and those agreements engaging two lawful entities via internet stands there as an media even if there is no awareness of its personal ownership. E-agreements must be carefully drafted to particularly meet agreement specification.

Sometime it is not important to stipulate conditions on the sale contract and therefore to append a phrase to a sale agreement saying that the acquired item becomes the assets of the purchase is tautological. This requirement is in accordance with the definition of distinctiveness of sale by itself. On top to this sale contract and comparable standard uniqueness of sale for instance price payment and subsequent ownership of the purchased item- the Shafi’i and Hanafi schools comprises of this group of conditions that branch from the particular character of the sale in question. But any sale conditions that are in accordance with the sale agreement do not nullify the sale agreement. In reference to this sale stipulation, if a person or an entity purchases an item on the provision that he becomes the owner, or if the seller conditions a price be paid on the object, or if it is a garment and the buyer wants to wear it, then the sale is permissible. This is because there is no breach of the sale agreement as stipulated in sale clauses and therefore the citing of these clauses is basically recognizing the nature of the agreement. In this case there will be no quashing of the sale.

The Stipulation Appropriate to the Sale Contract

There are two types of clauses appended to the sale contract even though not as a necessity to the main terms of sale agreement, these clauses makes it easy to comply with sale basic demands. They are suretyship clause (Kafala) and the pledge clause (rahan), whose characteristic entails the reasons of transaction and the legal structure of that particular sale transaction. For that reason, suretyship and pledge are acceptable terms under the entire Sunni Islamic Schools. Any requirement that is applicable to the agreement but not intrinsic in the nature as far as transaction is concerned does not nullify the sale agreement. We see that in such situations it is in accordance with its vital connotation and validates it; consequently it commands the prerequisite which is mandatory to the transaction. This applies to the scenario where an individual sells an item on demands that the buyer vows collateral (rahan) as an equal value to the price of the object. Alternatively, on provision that the purchaser provides a guarantor (Kafil) who provides security for the object’s price: in such circumstances the transaction is legally acceptable by good feature of juristic liking.

Analogical conclusions (Qiyas) do not allow the transaction for the reason that as a subject of rule, any condition which varies from the main contract cancels it. Suretyship and pledge clauses, being unrelated to the principal terms of transaction, have accordingly a nullifying effect on the agreement. On the other hand we have clauses allowing sale of objects based on the vow of collateral the same as a counter-value of the price the object and the same argument applies to suretyship. All above specifications emphasizes the right of the seller and thus do not nullify the sale agreement. Since the main reason of pledge is to get reimbursement, lawful permit depends on its proof of the right to reimbursement, which corroboration is a condition suitable to the sale agreement. Provided that the above is obeyed the sale contract is legal and therefore cannot be quashed.

The Stipulation that is Customary Practice

The Sunni Islamic schools decided that the allowed type of specification called “the conventional stipulation” those clauses are element of local tradition or custom (Urf). These conventional conditions are permissible to be lawfully binding regardless of the fact that they are outside to the fundamental stipulations of the sale agreement. We note that editorial 321 of Murshid al-Hayran has permitted this kind of requirement, so a condition which is not stated in the main contract nor proper to it, however which is general practice, is allowed. For example is an individual purchases a sole on provision that the seller attaches the sole to the shoe. On contrary, analogy preferences (Qiyas) Hanafi jurists does not allow such a demand as the supplementary phrase is not compulsory by the principal agreement and is of profit to barely one of the involved. Therefore, the clause cancels the transaction as a result on one entity benefiting at the expense of the other.

The Stipulation of Benefit to One of the Parties

Sometime we have contract stipulations that may benefit only one entity and therefore invalidate the transaction. The Hanbali and Maliki ruling deals with sale agreement conditions and were drafted in mindful disagreement to the Hanafi is evident from Ibn Qudama’s dismissal of the Hanafi ruling out against extra clauses that profit one of the constricting parties. Thus Hanbali and Maliki jurisprudence legalizes the incredibly same sale agreements whose appended clauses or sections were reviewed by Hanafi jurisprudence as quashing the entire agreement. We have de-legitimization of Hanafi School’s Hadith in two phase namely it is not there in the plausible hadith collections and secondly by stick on to a different description of the hadith in subject in which only transaction with two appended clauses are not allowed, the transaction agreements with one supplementary provision – different to the Hanafi verdict – are deemed lawfully binding. Hanafi conservatism concerning sale agreement stipulation were answered by Hanbali namely transaction with appended stipulations and addition of profitable condition under illegitimate gain (riba).

Hanbali and Maliki law elevates the concerned parties’ permission to the position of adequate stipulation for the legality of sale agreement. While the Hanafis regulation that mutual approval by the buyer and seller to the terms of the agreement is merely a basic stipulation of legitimacy and not enough to legalize the sale, the Ibn Taymiyya views things in a different way. Ibn Taymiyya’s justification of the sale agreement based wholly on the concurrence of the buyer and seller marks a considerable progress for independence of business in Islamic law. The parties have freedom lawfully to lay down whatever conditions they think is in their line of interest, free of customs, similar limitations put forward by Hanafi rule and norms.It is from these truisms that Ibn Taymiyya comes up with extensive conclusions about Islamic legality on agreements and sale of epochs and non-Islamic culture.