Introduction

They describe the past, control the present, and define the future. The 21st century is a time of incredible speed of information transfer as well as that of great forgetfulness. With individuals in-masse preferring easily-digestible information in the form of 10-second soundbites, it is easy to become driven by whatever the media shapes individuals out to be. At the same time, it is an age of the rebirth of public memories. Nowadays, museums are required not only to preserve and collect various rustics and antics of the years gone by, but also to demonstrate the history of people and nations without whitewashing or covering the bad parts.

There is a public demand to know all of history, and allow it to shape public identity. It is an arduous and painful process, often met with resistance, as past grudges, pain, and responsibility are brought upon future generations. The first instinct is to let bygones be bygones, but such an approach has inherent and implicit dangers to such. Art is a way to immortalize certain things and events, protect them from oblivion. At the same time, art is subjective, just as the views of individuals that make it. The purpose of this essay is to discuss the relationship between memory and oblivion, private and public recollection of events, and the way these concepts are reflected in the works of Walid Raad, Christo, and Jeanne-Claude, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres.

Memory and Oblivion

The relationship between memory and oblivion is an intricate one. Memory constitutes the knowledge of the past as experienced by the individual directly or indirectly (Loventhal, 1993). Oblivion, however, refers to the process of forgetting certain parts of it. There are numerous reasons for doing so. The primary function of giving up certain memories to oblivion is to free up space. Nobody can remember every single thing that has happened, especially when there is a choice to make between important and mundane memories (Loventhal 1993). That deemed routine and not worthy of being archived are forgotten to give way to something new. The second reason to condemn memories to oblivion is when it is inconvenient for everyone involved to remember something. Oblivion serves a social memory censorship function, by removing unwanted or unpleasant memories from existence in the scope of an entire society. Such actions usually take place when practices that have been considered valid for a long period suddenly become viewed in a bad light due to a change of a historical and societal paradigm.

An example of such would include the discussions of slavery in the US during the 1970s-1980s. During this period and up until the early 2000s, the American society, both on the side of whites and blacks, wished to simply erase the shameful pages in the country’s history (Loventhal, 1993). For whites, it meant being capable of treating the black population the way they deserved from the beginning, and for blacks – to forget the history of pain and exploitation, becoming capable of starting their history in the US from a clean slate (Loventhal, 1993). However, as it was discovered later, the black collective consciousness as a race cannot exist without a basis, which is their tragic history. Nor can whites make amends for the centuries of exploitation if they pretend that the atrocities of the past did not exist.

Another example involves Germany past the Second World War. Being the initiator of the world’s deadliest military conflict and responsible for the genocides, holocaust, and atrocities both domestically and on foreign soil, the German people attempted to “make amends and forget,” by distancing themselves not just from the events in their recent history, but also from any events that could have been considered relevant to it, through association (Loventhal, 1993). That included monuments, architecture, art, and other visual representations of pain and guilt. They too learned that oblivion is not the solution to these problems, since German history has acts of valor and heroism that define national character so closely interwoven with acts of outright barbarism, that removing them from the weave would not only dishonor the memories of their victims but also destroy the foundation upon which the national self-perception is built (Loventhal, 1993). Therefore, the relationship between memory and oblivion is an ever-changing one. Like waves and shores, they constantly shift, with the land sometimes claiming more, and other times being drowned in the water, with no end or solid solutions.

Private Memories and Public Memories

Private memories are what constitutes most of the art dedicated to specific events. They portray the viewpoint of a single individual about a specific event, at a point in time. Private memories are some of the most visceral experiences that a person may have, and sharing them is a potent and powerful tool to sway public opinion (Plate & Smelik, 2013). At the same time, they are biased, as the individual can rarely see the bigger picture of what is transpiring beyond their singular point of view. Public memories, on the other hand, are constructed from numerous private memories, records, and evidence, long after the event has transpired. The construction of public memories may have an insidious connotation, as parties and individuals in power tend to try and erase critical memories from the public consciousness, framing the history to benefit their agendas (Plate & Smelik, 2013). In that regard, public memory openly denies the legitimacy of private memories, robbing victims, survivors, and witnesses of their agency through public shaming, doubt, and ridicule (Loventhal, 1993).

The purpose of art, in that regard, is to create messages and symbols for public memory to etch the events of the past into the collective consciousness of many individuals, preventing them from being forgotten, and making the task of altering history through the manipulation of public memory difficult. It is the reason why dictatorships often target art and knowledge first, censoring books, music, sculpture, and other forms of audial or visual art to propagate a twisted version of history (Plate & Smelik, 2013). At the same time, the selection of some art over the other, just as cherry-picking private memories to make them public, is a form of manipulation of public memory, which could have a more devastating effect on the objective historical truth than outright destruction, since it is much harder to change and erase a wrongful framework of values than to build a new one where there was none (Plate & Smelik, 2013). At the same time, it begs the question of who has the right to choose or define history and memory, which is subjective by its very definition?

Lebanon Wars in Art by Walid Raad

Walid Raad is a Lebanese contemporary media artist, who is most known for his body of work dedicated to the Lebanon military conflicts of 1975-1991 (Haugbolle, 2005). Having been born in 1967 and having experienced wars first-hand, his art seeks to demonstrate how wars bring societal, infrastructural, and psychological devastation to both private and public memory. His works are part-truth, part-fiction, to enhance reality and experiences through personal perception.

In the terms of oblivion versus memory and private memory versus public, Walid Raad working to influence the public memory by creating dramatic and memorable visuals to affect not just the memory of his country, which still has plenty of private memories of the war, but rather to give the events that happened in Lebanon public recognition and etch them within the collective memory of humanity (Wroczynski, 2011). Raad creates an island in the sea of oblivion by revealing facts that the contemporary western audience is usually not exposed to, through the processes of public memory formation (Wroczynski, 2011). It is easy for western audiences to be ignorant about the tragic events happening around the world, which they and their governments did nothing to prevent (Wroczynski, 2011). When a distant war somewhere in the Middle East is out of sight and out of mind, it is much easier to do nothing about it (Wroczynski, 2011). What Walid Raad does is force a moral choice upon the audience – if you care, you have to do something about it. If you do not – that says something about your moral character. It is a powerful tool to use to create and resurge memory from the sea of oblivion.

At the same time, Raad’s art has a tremendous social impact back home, as it affects the formation of the collective memory of the nation. As it had already happened in many places affected by war, the first go-to solution to the years of pain and suffering is to simply numb it and engage in a state known as collective amnesia (Wroczynski, 2011). Raad recognizes the threat of such a practice, as a nation that forgets its history is forced to repeat itself. Therefore, his efforts to immortalize the destruction and suffering on all levels is a purposeful effort to prevent Lebanon from going through the same mistakes all over again and build a society rooted in peace, tolerance, and understanding rather than cruelty, pain, and martial might.

Memory and Oblivion in the Works of Christo and Jeanne-Claude

The relationship between the past and the present is contentious – one cannot forget one’s past, but must also not allow it to fully dictate the decisions in the present, and always look to build up a better future. Sometimes, a degree of oblivion is necessary for people to heal and focus on the future instead of engrossing themselves in the past. An example of such could be seen in one of the greatest achievements of Christo and Jeanne-Claude – artists from Bulgaria and Morocco, most famous for their large-scale installations and draping of buildings in fabric (Baal-Teshuva, 2001). Their greatest achievement is the Wrapped Reichstag, which had become a symbol for United Germany (Baal-Teshuva, 2001).

About memory, such a project has several symbolic meanings. It is noteworthy that 6 presidential administrations over 24 years have rejected the project before it was finally approved in 1994 and put on public view in 1995 (Baal-Teshuva, 2001). By that time, Germany has gone through great historical changes – from being brought down into rubble by the Second World War, through being partitioned between the East and the West during the Cold War, to being reunited upon the dissolution of the USSR (Baal-Teshuva, 2001). All of these events were extremely traumatic to the German collective psyche, creating a conglomerate of both individual and public experiences to generate a motif of pain and suffering ingrained into the people. Christo and Jeanne-Claude too were affected by all of those events, having lived through them, and wanted to make a statement with their art in a way to leave a positive impact on memory (Baal-Teshuva, 2001).

Like all art, theirs seeks to make an island in the sea of oblivion, though unlike that of Walid Real, theirs has a positive connotation. The white silvery fabric over a building that has become iconic for all of Germany’s decisions so far, good and bad, represents a new history page, stating that things will be much better from now on (Baal-Teshuva, 2001). It does not seek to erase history from public or private memory but has a firm message that the country and its people should focus more on doing better, instead of wallowing in the past. It is a message of reconciliation, unity, and healing, and has since become the symbol of new Germany and its return to Europe as a united state.

The Rejection of Framing of Memory in the Works of Félix González-Torres

What the two previous artists have in common is that both of them generate symbols and images in direct connection to memorable objects/events/locations to frame the public and private memories in a certain way. While it allows delivering the message intended by the artists, it also commits the act of destroying memories as much as creating them. It is said that creating objects that allow for direct demonstration of memories automatically eliminates any other interpretations of such, both for other people and for those who have created said objects (Tavano, 2020). A person who wrote a memoir cannot recall their experience outside of what has been written. The works of Felix Gonzales-Torres, an openly gay man and an AIDS patient, do not seek to create hard symbols for individuals to adopt as their own, therefore robbing them and their memories and experiences of agency (Tavano, 2020). Instead, his installations are meant to enhance the fluid and evolving qualities of memory by making people think.

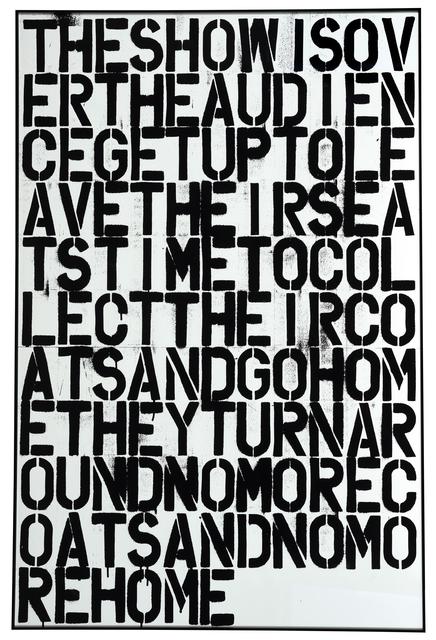

In his art, Felix focuses on the abstract and ephemeral nature of things, such as conventions, morals, borders, and perceptions of reality, viewing memory itself as a construct rather than an accurate and reliable reflection of reality. His art is meant to stimulate the viewer’s mind and come to their perceptions of their own experiences through mental effort. This is exemplified by one of his most famous works, titled “The Show is Over,” (Tavano, 2020). The letters in words do not have a clear separation between themselves, forcing the viewers to expend any effort to read the message. Upon reading it, there are enough blank spaces left to figure out what it means, and each member of the audience can reflect on their memories that connect with it (Tavano, 2020). In essence, his art targets private memories alone, by forcefully fishing them out of the amnesiac oblivion, and bringing them to the surface, making the people perceiving the art piece confront whatever it is they stowed away in the back of their minds, hoping to forget.

Conclusions

Based on the theory and the examples provided, it could be concluded that the relationship between memory and oblivion as well as private and public memory is a fluid and interchanging one. Oblivion claims some memories while pushing the others from under the water, and private/public dichotomy influences each other, with personal stories shaping public discourse, while the latter has a direct overarching effect on the individual lives of people.

As demonstrated in the works of three artists: Walid Raad, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, and Felix Gonzalez-Torres, the purpose of art about memory can vary from one person to another, and yet at the same time the messages they convey and the way they shape memories could all be valid, from a certain point of view. Memories are constructs, created from experiences and shaped by individual and public interpretations of thereof, built upon incomplete data and a plethora of biases rooted in personal experiences. One could say that there is no inherently correct or incorrect method of creating memories. At the same time, the consensus of the 21st century is that the injuries of the past should be accepted and dealt with, but never forgotten, lest their lessons vanish with them.

References

Baal-Teshuva, J. (2001). Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Dresden, Germany: Taschen.

Haugbolle, S. (2005). Public and private memory of the Lebanese civil war. Comparative Studies of South Asia, Africa and the Middle East, 25(1), 191-203.

Lowenthal, D. (1993). Memory and oblivion. Museum Management and Curatorship, 12(2), 171–182.

Plate, L., & Smelik, A. (Eds.). (2013). Performing memory in art and popular culture. New York, NY: Routledge.

Tavano, G. Y. (2020). What the activism and art of Felix Gonzalez-Torres and Gregg Bordowitz teach us about health and human rights. AMA Journal of Ethics, 22(9), 821-829.

Wroczynski, E. (2011). Walid Raad and the Atlas Group: Mapping catastrophe and the architecture of destruction. Third Text, 25(6), 763-773.