Introduction

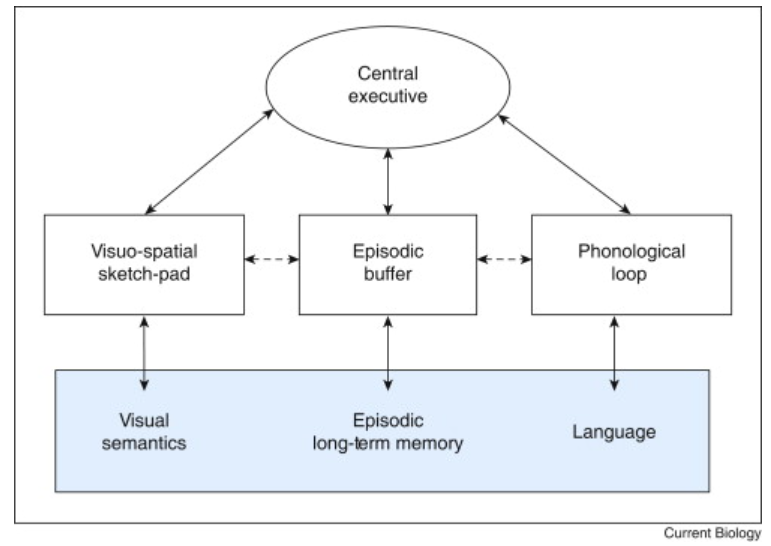

Consciousness allows us to feel what the world is like. Classically, the operation of working memory (WM) is a concept that has been linked closely to consciousness (Stein & Hesselmann, 2016). Prior research has indicated some WM processes operate based solely on conscious awareness, like storing and maintaining information for decision making (Baars & Franklin, 2003). One of the most influential accounts of WM is the 1974 Working Memory Model devised by Baddeley and Hitch, which represents WM as a multi-component system (Figure 1). WM is regarded as short-term memory, with different information linked to the different systems within. The model proposes that certain components act somewhat independently of one another, traditionally deemed to operate from conscious input (Soto & Silvanto, 2014). The multi-component model includes the central executive, an episodic buffer and 2 storage systems – the visuospatial sketch pad and phonological loop (Baddeley, 2010).

The visual working memory (VWM) is one of the most widely researched classifications of WM, also traditionally deemed to use and retain only consciously perceived information (Persuh, LaRock & Berger, 2018). The most emphasized component of VWM is its storage ability, described by the visual short term memory component. However, the VWM also pertains to the ability to maintain information for goal-directed behavior using executive functioning (Gayet, Paffen & Van der Stigchel, 2013). The human brain uses VWM to actively see or experience stimuli, both objective and subjective measures can operationalize this (Persuh, LaRock & Berger, 2018).

The advances in the understanding of blindsight have formed an integral part in igniting research to determine the link between VWM and consciousness. Blindsight occurs when despite lesions to the primary visual cortex, inducing cortical blindness, patients can respond to visual stimuli that have not entered visual consciousness (Nakano & Ishihara, 2020). Prior studies have revealed that some goal directed behavior can occur independently of visual consciousness, indicating an ability to encode unconscious visual information in the visual perceptual system (Dutta et al., 2014). Due to the suggestion that VWM can operate on non-conscious input, research over the recent decade has therefore challenged the idea that WM and consciousness are tightly connected and explored VWM as a potentially non-conscious method of information processing (Persuh, LaRock & Berger, 2018).

However, despite a multitude of research over the past decade, studies have focused on the memory storage function of VWM (Ansorge, Kunde & Kiefer, 2014), leaving a prominent gap in the research regarding the relationship between the executive function of VWM and consciousness. The executive function involves the central executive, which acts as a control of attentional processes rather than a storage system. This component allows the VWM to either attend to or ignore certain information (Nakano & Ishihara, 2020).

The present study seeks to address the gap in the research regarding the executive function of VWM and consciousness. In contrast, presenting a new combination of methods adapted from significant studies in the research field. Recently, Bergström and Eriksson (2017) presented a paper using continuous flash suppression (CFS) to create a non-conscious paradigm in which a delayed match-to-sample task was undertaken. fMRI was used throughout this study to investigate the non-conscious short-term retention and associated neural correlates. This study demonstrated non-conscious information could be maintained for short-term retention. The present study seeks to use a modified Bergström and Eriksson (2017) method, adapted to explore executive functioning. Thus, contributing to a novel area of research in an attempt to provide additional research for unconscious content and processes in WM, potentially providing a model for behavioral selective responses in other areas of WM.

Aims and Hypothesis

To corroborate current findings and address methodological challenges found in prior research of VWM and consciousness (Velichkovsky, 2017) this study seeks to determine executive function of the VWM to compare the process which requires a use of multiply stored visual information, using a dual model of a CFS and delayed match-to-sample paradigm.

- Aim: The aim of this study is to determine the relationship between VWM and unconscious content identification using a dual CFS and delayed match-to-sample paradigm to determine executive functioning as an unconscious process.

- Goals: This study seeks to understand the relationship between consciousness and WM. This study will follow a modified structure of Bergström and Eriksson (2017) experiment on non-conscious WM to determine what WM processes can occur independently of consciousness awareness, with a focus on the central executive of VWM.

- Hypothesis: The working hypothesis is that the objective visual masking paradigm measurement will show above chance level results, despite subjective measurement scores indicating visual cues as not consciously seen.

Proposed methodology

The given research follows a quantitative methodology with 40 participants being recruited, aged 18-30. All participants must have normal vision and be right-handed. Written consent will be confirmed. This study will use a within-subject design, where each participant will undergo a dual CFS and delayed match-to-sample task in 3 trial conditions: 120 conscious, 180 non-conscious, and 60 with no target, which serves as the baseline. Each trial will be randomly selected. Participants will judge whether the two objects presented amongst a CFS masking task are the same object and in the same position.

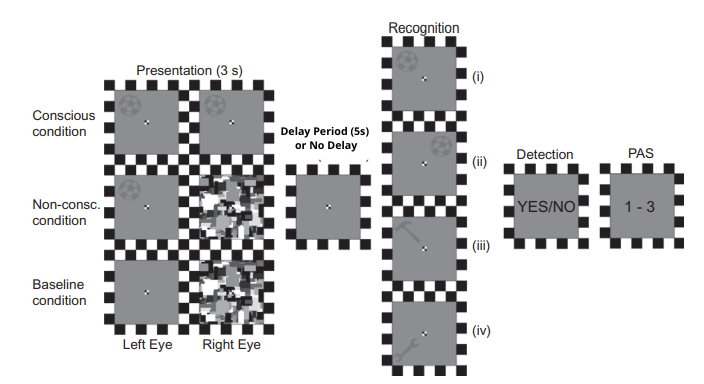

The present research will adapt the Bergström and Eriksson (2017) methods, without the fMRI component, to focus on the objective measure tasks (Figure 2). The Bergström and Eriksson (2017) study noted the long delay period (5-15s) used in the fMRI session likely decreased performance. Therefore, this modified method will only test the objective performance measures of CFS and the delayed match-to-sample task. Instead of the 5-15s delay period, we will randomly intermix trials where performance is assessed immediately after the presentation of stimuli (i.e., no delay period). A visibility rating using a perceptual awareness scale (PAS) of 1-3 (1=no perceptual awareness) will act as a subjective measurement of the visual cue.

This will address the relationship between WM and unconscious content identification (aim) by enabling the executive function of VWM to undertake information manipulation. To achieve the goals of this study, the CFS component of the survey will render stimuli non-conscious so that the participants can undertake the delayed match-to-sample task. The forced-choice component of this will both directly measure consciousness and indirectly measure storage and manipulation of information ability. This will assist in determining WM, specifically the executive functioning component that can occur independently of consciousness.

Procedure

A sample will be presented for 3s, of a grey silhouette of a tool positioned in 1/4 of the screen. The tool and position will be randomly selected. This sample will be presented either to both eyes at same time (conscious trial) or to the non-dominant eye, while coloured squares of random composition are flashed to the dominant eye to compress the sample from conscious experience (non-conscious trial). The baseline trial will consist of coloured squares of random composition flashed to the dominant eye, while an empty gray background is presented to the non-dominant eye (same visual experience as non-conscious). Following this, participants will experience either 5ms delay period or no delay period, randomly selected. Then the memory probe will be presented. Participants must recognize if the tool is the same object + position (full match), same object + different position (identity match), different object + same position (position match) or different object + different position (non-match). The answer of Yes or No will allow for detecting response if participants thought a sample stimulus was presented at all. Visibility rating will then be scored on a perceptual awareness scale (PAS) from 1 (no perceptual awareness), to 2 (was aware of something), and 3 (clear/almost clear perceptual experience).

Note. One trial includes CFS presentation in the 3 conditions: conscious, non-conscious & baseline. Forced choice delayed match-to-sample task includes object 1 shown in presentation columns, and object 2 shown in recognition column, followed by detection (yes/no) and visibility rating task using the PAS.

Data Analysis Plan

Trials from baseline and non-conscious conditions of visibility rating 1, no perceptual awareness, and conscious condition rating 3, clear/almost clear perceptual experience, will be used in data analysis. Signal detection theory (d’) will be used to determine delayed match-to-sample (Table 1) and detection task performance (Table 2).

Table 1. Recognition of delayed match-to-sample task

Note. Delayed match-to-sample task, for recognition d’, the signal is defined as object identity and position. Hit is classified as correct object identity + position, FA is classified as partially correct object identity or position.

Table 2. Detection task Results

Note. Detection task measured by response accuracy of each participant for each trial. A ‘hit’ is classified as presence of the sample + a ‘yes’ response, a FA is classified as absence of the sample (baseline trials) + a ‘yes’ response.

We will calculate the percentages of correct responses including hits and CRs and incorrect responses including miss and FAs. SPSS will be used for all data analysis. To address the hypothesis, we will run a t-test to compare participants percentages of correct and incorrect responses to compare against chance level results (above 50%).

The visibility rating task will compute d’ to confirm the effects of the stimuli where PAS 1 classification will be rated as not seen and PAS 3 classification rated as seen. Using these subjective responses d’ mean will be computed using an additional t-test. It is expected that we will achieve scores above chance level despite visibility rating indicating no perceptual awareness.

Significance and Innovation

The role of storage function in the VWM is a heavily research topic, however few studies have focused on the executive function component (Nakano & Ishihara, 2020). This project is interesting in consciousness research as it uses a novel form of the Bergström and Eriksson (2017) experiment, adapted to explore the role of executive function. The present study also incorporates adjustments to this study, addressing limitations of excluded criteria and long delay period. A set of randomly intermixed trials of immediate performance assessment was also added. The forced-choice component combats subjectivity bias that previous studies have failed to consider. These adaptations present an enhanced and novel methodology geared to determining the role of VWM executive function as non-conscious information process.

Furthermore, if the goals are achieved, unconscious WM executive function will be determined by selection recognition to the visual items presented, being above chance level across all trials. Finding a link between executive functioning and non-conscious cognitive processes could allow for future studies to explore unconscious execution of WM tasks. Additionally, these findings could help promote further research to identify whether all components of WM processing can occur unconsciously, not just the VWM. In contrast, participants’ achieving results in the below or at chance level in the paradigm of this study would suggest that executive function may not play a role in non-conscious information processing. The paper can support the view that the central executive of the VWM may be a pivotal link to the conscious experience of visual input.

References

Ansorge, U., Kunde, W., & Kiefer, M. (2014). Unconscious vision and executive control: How unconscious processing and conscious action control interact.Consciousness and cognition, 27, 268-287. Web.

Baars, B. J., & Franklin, S. (2003). How conscious experience and working memory interact.Trends in cognitive sciences, 7(4), 166-172. Web.

Baddeley, A. (2010). Working memory.Current biology, 20(4), R136-R140. Web.

Bergström, F., & Eriksson, J. (2018). Neural evidence for non-conscious working memory.Cerebral Cortex, 28(9), 3217-3228. Web.

Dutta, A., Shah, K., Silvanto, J., & Soto, D. (2014). Neural basis of non-conscious visual working memory.Neuroimage, 91, 336-343. Web.

Gayet, S., Paffen, C. L., & Van der Stigchel, S. (2013). Information matching the content of visual working memory is prioritized for conscious access.Psychological Science, 24(12), 2472-2480. Web.

Nakano, S., & Ishihara, M. (2020). Working memory can compare two visual items without accessing visual consciousness.Consciousness and cognition, 78, 102859. Web.

Persuh, M., LaRock, E., & Berger, J. (2018). Working memory and consciousness: the current state of play.Frontiers in human neuroscience, 12, 78. Web.

Soto, D., & Silvanto, J. (2014). Reappraising the relationship between working memory and conscious awareness.Trends in cognitive sciences, 18(10), 520-525. Web.

Stein, T., Kaiser, D., & Hesselmann, G. (2016). Can working memory be non conscious?.Neuroscience of Consciousness, 2016(1). Web.

Velichkovsky, B. B. (2017). Consciousness and working memory: Current trends and research perspectives.Consciousness and Cognition, 55, 35-45. Web.