Introduction

Technology advancements continue to influence perspectives and practices of branding, but important constructs of branding are still relatively unchanged from what they were a decade ago. However, the entire concept has leapfrogged when observed in the context of ten decades ago.

The change has been from a marketing ideology and its various associated changes to a branding ideology. Branding has shifted from being an accessory of corporate strategy to become a critical success factor for organizations, individuals, special interest groups, institutions, and movements alike.

Marketers and brands can now reach targets in the context of their daily lives and routines. This ability presents various opportunities and threats.

Growth in brand reputation also increases stakeholder scrutiny of the brand. Going forward, it will be critical for all practitioners and scholars to embrace the fact that brands are ‘performative’ because they transform the context of their application and the subjectivity of participants (Nakassis 2012).

Review of academic literature on recent trends in branding

The rise of branding as a corporate activity in the recent decades has been successful, but the trend is now facing challenges from the rise of anti-brand activism (Palazzo & Basu 2007).

These two trends come from a societal transition from an industrial to a post-industrial society, which, coupled with globalization, is calling for brand success to encompass more than just superior product performance. Corporations now have to think beyond performance and into the social behaviour of their brand as evoked by their brand (Palazzo & Basu 2007).

According to Wang et al. (2012), consumers deploy superstitions to fill the void of unknown company offerings when they first encounter a brand logo. They also use the superstitions to evaluate a brand logo and judge benefits arising from its offerings. Individuals who believe in fate see less need to seek control over their fortune or fate in an uncertain market condition (Wang et al. 2012).

Therefore, they take less cues from external information sources like brand logos. On the other hand, people can form positive attitudes toward a brand logo because of their perceived benefits, as indicated by the images and connotations arising from psychological beliefs.

In such cases, strong beliefs influence positive associations and evaluation of brand logos (Wang et al. 2012). In general, companies must appeal to people’s psychological belief orientations to influence positive attitudes shown by their consumers, which should lead to a favourable performance of company offerings in a target market.

Even with the constant flux of the environment for corporate branding, many organizations still conceptualize themselves as stable entities (Melewar, Gotsi & Andriopoulos 2012). As firms continue to focus on consistency and continuity in their branding efforts, the external and internal environments are increasingly becoming blurry.

Rather than merely change corporate brands to reflect changes in internal and external environments, organizations have to establish traditions, cultures, and strategies that make their corporate branding tactics fluid and reflective of the dynamic internal and external environmental needs (Melewar, Gotsi & Andriopoulos 2012).

Nations are also embracing place branding in a corporate way and coordinating the activities of their various state-level organizations to create a common brand (Dinnie et al. 2014). With integrated communication marketing approaches, nations act like individual firms and reach diverse audiences with a constant message.

They focus on having optimum market coverage with the least amount of investment. This comes in the wake of concerns about a nation’s reputation and its competitiveness, especially the attraction of foreign direct investments and export of services.

Place branding is a newer concept than product branding and follows the many principles of brand management. However, place branding has multiple stakeholders and decision-makers, while product branding is mainly tied to specific organizations and their stakeholders (Sharp 2010).

Recent trends in branding of countries force the development of efficient and systematic methods to align key stakeholder groups. Branding of places is now more than a focus on particular environments and advanced infrastructures or other attraction points (Dinnie (ed.) 2011).

States that have no explicit branding activities are ill-equipped to compete for economic, political, and social attention. Most countries are now changing the definitions of traditional diplomacy to reflect market needs and view collaboration and cooperation at an international level as avenues for integrated marketing communications (Dinnie et al. 2014).

Directors of different state agencies, embassies, or state affiliated organizations continue to increase the frequency of informal meetings that may not be explicitly about representing a country’s economic or political agenda, but create a convenient channel for future formal negotiations. Such activities aim to soften the nation brand reception by hosts (Dinnie et al. 2014).

Place branding lays emphasis on brand identity elements such as mission, vision, values, personality, and distinguishing preferences and benefits of a place (Sharp 2010). Practitioners are looking at relationships of influential stakeholders as key areas to review when creating a place brand because places have a number of stakeholders in them and rely on their brand equity.

The main aim of intervening on relationships among stakeholders is to ensure that they live up to the promise of the brand, just like company employees are supposed to live the promise of their organization’s brand.

In addition, the growth of brand management and a common use of the term now place a brand image on everything. Political parties, schools, museums, national or international sporting events, activism campaigns, military, celebrities, and any individual or entity now is understood as a brand and managed as a brand. As such, branding has become a business imperative, rather than merely a marketing decision (McKee 2014).

Partner brand attitudes continue to have positive effects on the attitudes towards brand alliances and international brand alliances (IBA) are becoming a common feature for global companies.

Just like marketing entry strategies, firms on a global scale are increasingly going for IBA because they want the benefits of quickly gaining trust, knowledge, expertise and established distributed channel, as well as the category’s reputation and native brand value (Li & He 2013).

Nevertheless, consumer ethnocentrism continues to play a part in an actual brand performance in foreign markets through alliances or direct entry. In spite of this, there continues to be a push for branding strategies that rely on product reputation to grow brand reputation and go past the market challenges caused by consumer ethnocentrism (Li & He 2013).

Although the concept of corporate branding is well known, there continues to be confusion and conflicting literature concerning corporate branding, corporate identity, and corporate reputation (Olins 2008).

On one part, corporate branding focuses on relevancy to customers, while corporate reputation concerns the legitimacy of the organization with respect to stakeholders. On the other hand, there is a view of corporate brand being an integral factor for building corporate reputation to all stakeholder groups.

As corporate entities attempt to fix their brands and use them as unique resources for competitive advantage, they create heightened importance on their corporate affinities, products and services, as well as social responsibility programs. While some firms are choosing to focus on particular elements of identity, many other companies choose to embrace a wholesome approach that covers the entire range of options.

Branding is, therefore, becoming a means of achieving a desired corporate identity and it is no longer a tool for marketing alone. Consumers are becoming aware and critical of organizations’ impacts on society and ecological environment. As argued earlier, companies have to shape consumer perceptions about their products and their overall practices and roles in the society.

Other than simply work on the associated reputation, organizations or individuals embracing a corporate brand also have to cultivate a brand personality, which mimics a set of human characteristics identified by all stakeholders.

Stakeholders’ behaviour, attitudes, and intentions collectively constitute the brand equity of a place. In the same manner, values, actions, and words of all employees in an organization make up its personality (Olins 2008).

Technological advancement, especially internet and mobile communications, have now enabled brands to reach people in intricate ways.

However, many companies still make the mistake of perceiving the medium as a stand-alone platform, while others go on to dominate market shares and improve their brand performance by focusing an entire ecosystem that uses various media appropriately (McEwen 2005). The following figure shows brands that use colour as a medium of communication without losing their identities.

Branding practice in the last ten decades

In the 20th century, industrial societies had cultural homogeneity and early 21st century societies were moving toward fragmented pluralistic cultures (Palazzo & Basu 2007). In the past, people had traditional sources of identity, which gave them a stable set of expectations.

There were limited questions about brands and people had no or limited reflexive processes of identity formation. Consumption had not picked up as a key part of the society, until the late 20th century; therefore, branding activities and intentions were less concerned with self-constructing activities (Palazzo & Basu 2007).

In the early 1900s, trade was an activity restricted to geographically defined locations. The period was also filled with explorations and colonialism; thus, its commercial ideology was a product of mercantilism.

The overall trading environment was characterized by strong governmental control, monopolies, search for exotic substances, special focus on elites, exploitation of colonial resources, and the use of high tariffs to influence the trade direction (McKee 2014).

The 1920s witnessed the rise of chain stores and the marketing ideology created a world view of marketers as people who mastered the complexities of national advertising campaigns, sales, and management of product policy to earn profits. Later on, marketing became the process of transferring goods through commercial channels. Such a channel started from a producer and ended at the consumer.

Marketing became a service that marketers offered at a commercial rate. Meanwhile, producers began focusing on more than the subsistence consumption market and they sought to provide rare or seasons produced throughout the year to increase consumption and boost profits.

The industry was concerned mainly with profits and opted to overprice and deceive consumers to make ends meet in a highly competitive environment (McKee 2014).

Marketing as a concept of consumer orientation began with the end of the Second World War. Scholars developed management concepts and behavioural theories, such as the marketing mix (Dinnie et al. 2014). At the same time, consumer appreciation began and marketers focused on the need to be economical and the desire to emulate people of high status (McKee 2014).

Consumers, faced with unlimited choices, became judgmental through their purchase behaviours and criticisms. Marketers faced accusations of creating artificial problems to increase product sales.

The media became an influence of branding developments and consumer criticism, a trend that proceeded into the 90s decade. The period between the 1970s and late 1980s also saw the shift from marketing concepts to branding concepts and ideologies (Dinnie et al. 2014).

In the last few decades, corporate brand appeared as conscious decisions by senior management to distil and make known the attributes of the organization’s identity.

They relied on a clearly defined brand position to achieve this goal. Following the premise, corporate brands in the second half of the twentieth century became promises that organizations made to shareholders and the promises were steered by management (Melewar, Gotsi & Andriopoulos 2012).

Brands that disappeared in the last ten years

Piene Webber, one of the biggest brokerage firms on Wall Street. Altoids was a food processing firm that was a household name and it later disappeared. The brand disappeared after the acquisition of the firm by Kohlberg. Another brand yet to die, but showing signs of dying is IBM that is no longer making consumer products like laptops (Daily Finance 2014; (Mont 2011).

Pan Am international airline was a major airline company whose brand is no longer recognized due to the collapse of the company (CNBC 2014). Compaq is a computer manufacturing company that has vanished too (Hess & Sauter 2013).

Brands that have grown

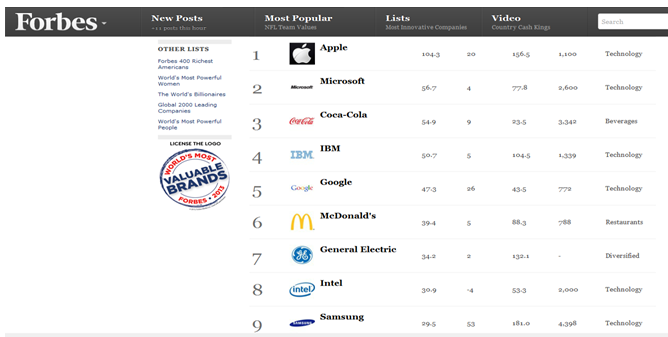

Meanwhile, other brands have grown in the past ten years and they include Google, LG, Audi, SAS, Samsung, and Toyota because the companies responsible for these brands are doing business that is relevant to the needs of consumers. Google is an internet company that also provides smartphone operating systems. Audi is a car manufacturers, Samsung is similar to LG in scope of work, while Toyota is a car manufacturer.

Brands that have delivered great commercial results

The dominant companies in the ‘World’s Most Admired Company’ list are praised for their brand power. On the other hand, activists against brand, corporate identity, and multinational companies also target the ‘World’s Most Admired Company’ list, with the top companies in the list receiving the greatest backlash.

Examples include Wal-Mart, Apple, and Starbucks (Palazzo & Basu 2007). Brands like Samsung and Toyota have been at the forefront of technology innovation and have created meaningful additional to innovations that ease ordinary tasks and are less harmful to the environment.

Hypothesis of the future of branding

The global cultural environment is complex, overlapping, and disjunctive. In this regard, it is impossible to understand it as separate conceptual entities divided by characteristics of producers or consumers, surplus or deficit, and centre or periphery (Palazzo & Basu 2007).

Societal transformation continues to influence identity-driven consumption and identity-driven activism. Corporate branding will continue to encourage consumers to see themselves as part of a brand narrative, but it will also raise ethical issues.

Therefore, successful corporate branding will only be possible when tackled with adequate corporate social responsibility perspectives (Palazzo & Basu 2007).

With high stakes being placed on brand identity among consumers and shareholders, businesses will face a heightened risk of severe reputation and financial backlashes when their branded values go contrary to their actual brand behaviour, or when they become front-page news for the wrong reasons.

As the no logo brigade continues to gain followers, top recognized brands will continue to become the most targeted references for external critics. They will, in turn, have to invest more than they currently do to balance the positive and negative associations of their brand. Branding will, therefore, not be a competitive strategy alone, but also a survival tactic in reaction to rising anti-brand activism (Romaniuk & Nenycz-Thiel 2013).

A saturated populace in Western Europe and North America may decide to stick to present consumption levels (McKee 2014). The continued focus on increasing consumption may stagnate due to a lack of a relevant response from the market.

In this regard, there will be a reinvention of marketing that must balance sustainability needs and accept the fact that ‘wants’ rely on cultural influences and would be shaped by marketing and other forces (Ottman 2011). Already, the most recognized brands in the world, Apple and Google, as reported by Gross (2014), are focusing on socio-physiological and aesthetic enhancement of their brands (McKee 2014).

Summarised results of interview with 3 experts

The following paragraphs represent a summary of results from interviews done with three experts on the subject of branding. The main interview questions precede the interview summary in each paragraph.

What challenges are both practitioners and researchers going to face concerning branding? – The rise of a global culture does not infer an amalgamation of tastes and preferences of consumers. Both practitioners and scholars have to consider the implications of their actions towards their overall goals and the provisions available for them to do so.

What is your take on the adoption of Web 2.0 technologies and social networking as tools for branding? – Part of the move by branding strategists to embrace mobile technologies and social networks or other forms of Web 2.0 technology has been the fact that a critical population mass is already using these features.

What can you advice firms seeking international brand alliances? – When considering international brand alliances, partner brands will have to seek to have their brand appear first because this has an effect of enhancing the brand attitude. The arrangement should follow the contribution of a brand to the alliance, with the more resourceful brand taking the first position.

What is your take on the future of place branding? – As part of the demands to improve place brands, such as countries or cities, practitioners will face increasing pressure to look at identity and equity. On one side, there is the brand identity that integrates facets of internal stakeholders living and constituting the brand.

“Building alliances is a tough thing to do and a brand for a company is life reputation for a person; therefore, it pays to do the hard things well.” – Jeff Bezos, CEO of Amazon (Goodreads 2014).

One way for academics to explore this subject further

Scholars have to conceptualize processes that increasingly manage corporate brand meaning within and outside organizations. While doing that, the conceptualizations should also remain consistent and coordinated (Melewar, Gotsi & Andriopoulos 2012).

With the paradox of focusing on individual or the organization level, the research will have to embrace a multiple-level analysis that captures the individual level experience, interpretation, and influence of corporate brands and one that seeks to understand and explain motivation for employees to live the brand and deliver on the brand promise (Rauch 2012).

Rather that view the relationship of brand formation between stakeholders and organizations as one-directional, the new research focus should be on the multi-direction perspective of influence and the dynamic natures of an emergent relationship that builds or destroys brand identity.

Future research should look into empirical evidence for the constructs of corporate identity, corporate brand, and corporate reputation to provide additional understanding of their relationships, amid the growing influence of branding as an ideology.

One way for practitioners to respond to trends identified

Marketers must continue to embrace the dynamic nature of the marketing ideology and follow the present trend of seeing branding as more than product function. They should include salience of reputation in their strategies; otherwise, they might lose their jobs as their organizations rapidly decline due to unfavourable market conditions caused by a sudden change in their reputations.

A focus on reputation does not imply abandonment on quality functionality. Therefore, it is important to avoid conflicts of branding and marketing ideologies in the formulation and execution of strategies. Nevertheless, branding will overtake marketing in glamour, sophistication, and virtue.

Thus, both marketing and branding goals will have to move beyond commercial goals and embrace the use of expressions, tangibility, imaginative language, and artistic visualizations (McKee 2014).

Reference List

Dinnie, K, Melewar, TC, Seidenfuss, K-U & Musa, G 2014, ‘Nation branding and integrated marketing communications: an ASEAN perspective’, International Marketing Review, vol. 27, no. 4, pp. 388-403.

Gross, D 2014, Study: Google leapfrongs Apple as world’s most valuable brand. Web.

Li, Y & He, H 2013, ‘Evaluation of interantional brand alliances: Brand order and consumer ethnocentrism’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 66, pp. 89-97.

McEwen, WJ 2005, Married to the brand: Why consumers bond with some brands for life, Gallup Press, New York, NY.

McKee, S 2014, Power branding: Leveraging the success of the world’s best brands, Palgrave MacMillan, London.

Melewar, TC, Gotsi, M & Andriopoulos, C 2012, ‘Shaping the research agenda for corporate branding: avenues for future research’, European Journal of Marketing, vol. 46, no. 5, pp. 600-608.

Nakassis, CV 2012, ‘Brand, citationality, performativity’, American Anthropoligist, vol. 114, no. 4, pp. 624-638.

Olins, W 2008, Wally Olins: The brand handbook, Saffron Brand Consultants Ltd, London.

Palazzo, G & Basu, K 2007, ‘The ethical backlash of corporate branding’, Journal of Business Ethics, vol. 73, pp. 333-346.

Romaniuk, J & Nenycz-Thiel, M 2013, ‘Behavioral brand loyalty and consumer brand associations’, Journal of Business Research, vol. 66, pp. 67-72.

Sharp, B 2010, How brands grow: What marketers don’t know, Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

Wang, YJ, Hernandez, MD, Minor, MS & Wei, J 2012, ‘Superstitious beliefs in consumer evaluation of brand logos: Implications for corporate branding strategy’, European Journal of Marketing, vol. 46, no. 5, pp. 712-732.