Introduction

Islamic branding has recently created a lot of attention in the academic world for its faith-based strategies in the marketing field. Evidence of this interest comes from the introduction of Islamic academic journals that investigate the intricacies of the marketing model (Yusof, 2014). Similarly, the start of the Islamic branding consulting service shows that many professionals are curious about how Islamic branding works. However, the status of Islamic branding does not (merely) emerge from the interest and demand for Islamic commercial services; it stems from the weaknesses and gaps of conventional branding methods and their failure to appeal to the needs of all market segments.

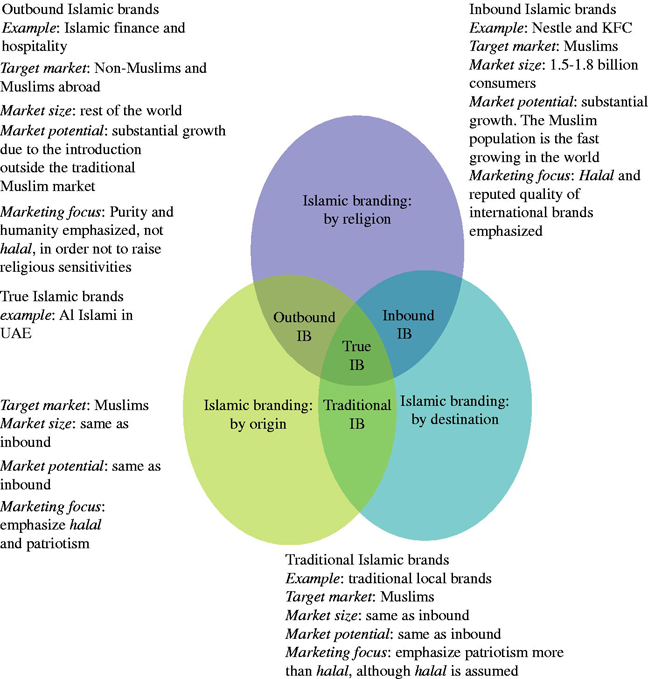

People do not have a definitive understanding of Islamic branding. To clarify this issue, Yusof (2014) says Islamic branding mainly focuses on promoting halal. This paper widely uses this concept in several sections of this paper because it denotes what is acceptable, or lawful, to the Muslim faithful. Many scholars have adopted the above definition of Islamic branding to underscore its importance in global commerce. For example, Yusof (2014) uses three criteria to explain Islamic branding by emphasizing the importance of using the country of origin, target audience, and whether it is Halal (or not) to define whether marketing campaigns are Islamic brands, or not. The following diagram shows this conceptual framework

The diagram above shows that Islamic branding stems from an Islamic belief system, which shapes people’s perceptions about products and services. Therefore, perception is the moderating variable among the three pillars of Islamic branding. Alijumani and Siddiqui (2012) use this understanding to say that many Muslims depend on their perceptions for supporting Islamic branding, as opposed to their Islamic values.

Based on the above understanding of Islamic branding, this paper explores the intricacies surrounding the marketing concept by investigating the differences between Islamic brands and conventional brands. Similarly, this paper seeks to understand what Islamic branding has to offer (that is unavailable today) and highlights the weaknesses, strengths, threats and opportunities of the marketing concept. These analyses provide the platform for exploring examples of countries that have used (or use) this marketing model. However, before delving into the details surrounding this analogy, it is important to comprehend the Islamic norms of ethics that underscore its application.

Islamic Norms of Ethics

Free Enterprise

Islam allows its followers to make a living in whichever way they please. However, whichever business a person chooses to do, he should manage it within the framework of the sharia law. Similarly, whichever business a person chooses to do, he must manage it responsibly. Simply, this provision requires businesspersons to choose lawful activities and shun haram (Azmi, 2014).

Keenness to earn legitimately

As shown above, Islam emphasizes the need for traders to earn legitimately. For example, the faith prohibits its followers from wrongfully taking the property of another person (Ahmed, 2012). Regarding this provision, the Quran says, “Do not devour one another’s property wrongfully, nor throw it before the judges to devour a portion of other’s property sinfully and knowingly” (Azmi, 2014, p. 5). Overall, all Muslim traders are supposed to earn their living by engaging in legitimate practices only. The same provision also requires its followers to distance themselves from engaging in dubious business transactions.

Trade through Mutual Consent

Islamic norms of ethics require all business transactions to occur through the mutual consent of the parties involved. In this regard, all business transactions that occur under duress (or coercion) are haram. Based on the same logic, the faith prohibits its followers from exploiting people’s plight by charging exorbitant prices (Obaidullah, 2005). This ethical principle stems from a verse in the Quran, which says, “O you who believe! Eat not up your property among yourselves in vanities: but let there be amongst you traffic and trade by mutual goodwill: nor kill [or destroy] yourselves: for verily Allah has been to you most Merciful” (Azmi, 2014, p. 6). This assertion highlights two main factors that underlie this business principle – mutual consent and gainful exchange.

Truthfulness in Business Transactions

Islamic norms of ethics require its members to be truthful in their business transactions. Azmi (2014) says the threshold for truthfulness is often very high. By being truthful, Allah promises to reward merchants in heaven. However, if they are deceitful, they will not only affect their businesses (interpersonal relationships), but also negate any heavenly gains they would have received. The logic behind this ethical principle is that Allah always blesses truthful traders.

Trustworthiness in Business

Trust is an important business virtue in Islamic and non-Islamic businesses. However, in the Muslim community, this virtue is incumbent for all its members. Particularly, this is true for Muslim traders. Simply, this virtue demands that all businesspersons should be sincere and have pure intentions in their commercial transactions. Relative to this assertion, Azmi (2014) contends, “Muslim traders should avoid fraud, deception, and other dubious means in selling their merchandise” (p. 9).

Generosity and Lenience in Business Transactions

Generosity and leniency in business transactions demand that all traders should conduct their businesses decently. For example, Islamic norms require traders to bargain generously and demand their debts, decently. The Quran says that Allah’s mercies are on the people who practice this principle (Azmi, 2014).

Honoring and Fulfilling Business Obligations

Similar to western business ideals, Islam requires its followers to meet their contractual obligations, fully. Alongside this obligation is the requirement for merchants to show honesty, trust, and truthfulness in their business transactions. Therefore, Islam considers those who break their business promises, or fail to meet their contractual obligations, as traitors and hypocrites. To safeguard the interests of all the stakeholders, it is necessary for all parties to specify details about their business contracts (Azmi, 2014).

Fair Treatment of Workers

Islamic norms of ethics outline the specific terms of engagement for reducing employer-employee conflicts. This way, it strives to promote love and “brotherhood” between both parties. The same principle outlines the need for employers to mind the welfare of their workers because it is their moral and religious duty to do so. Good working conditions and fair wages are among some issues that emerge in this analogy. In sum, Islam says, “Those are your brothers who are around you. Allah has placed them under you. So, if anyone has someone under him, he should feed him out of what he himself eats” (Azmi, 2014, p. 12).

How does Islamic Branding respond to these Norms?

Halal Certification

Most “Islamic products” should have a halal certification. Before products get this certification, they should comply with existing Islamic norms of ethics (defined above). If they contravene some (or any) of these norms of ethics, they cannot be branded as “Islamic products.” In some Muslim countries, the government undertakes the certification process. However, in other countries, mosques and other religious centers perform the same role.

Competitive Products

Islamic branding does not promote exorbitantly priced products and services. This is in line with Islamic norms of ethics, which prevents traders from exploiting their customers. Obaidullah (2005) and Musa (2013) say this principle manifests in Islamic finance because, although there are more than 400 Islamic banks in more than 50 countries, worldwide, none of them charge prohibitive costs to their customers. Instead, such financial institutions offer highly competitive prices for their services.

Sharia-Friendliness

Islamic branding concentrates on promoting products that comply with sharia laws. Most of these products exhibit values and beliefs that follow Islamic norms of ethics. For example, the Said Business School (2010) says Islamic branding supports products that show “honesty, respect, consideration, kindness, peacefulness, authenticity, purity, patience, discipline, transparency, modesty, community, and dignity” (p. 19). Products that do not demonstrate (or contravene) the above values are excluded from Islamic branding. For example, a while back, some Muslims introduced “Islamic Cola” as a new beverage for Muslim consumers. However, it failed to “catch on” because it was not a sincere product. Critics said there was nothing Islamic about it, except the name; instead, its proponents wanted to profit from a wider political history of the “Cola” brand (Said Business School, 2010). Therefore, Islamic branding is empathetic to sharia values and follows Islamic norms of ethics.

How does Islamic Branding Differ from Conventional Branding?

In the western world, conventional branding promotes the consumption of goods and services. This type of branding does not transcend the commercial value of marketing. In other words, businesses are there to make a profit and they seize every opportunity that exists to increase their revenues. However, Islamic branding does not only aim to make a profit; instead, it strives to attach marketing activities to faith. This is why the diagram below shows that Islamic branding has three levels of operations – branding by religion, branding by destination, and branding by origin (The Wire, 2008).

According to the diagram above, the most exclusive level (top level) mainly abides by sharia laws (as described above). Its compliance applies to certain types of branding (only). For example, sharia laws outline how Islamic businesses should brand food products and financial products. Beyond that, the second level of Islamic branding appeals to products that Islamic-rooted companies make but have a mass appeal. For example, airline companies and telecommunication companies that have their roots in Islamic organizations appeal to this level of organization. The third level of Islamic branding outlines products that have no religious affiliation, but still come from Islamic countries. Relative to this branding level, The Wire (2008) says that most Turkish products appeal to this type of Islamic branding. Although few people make the distinction between the three levels of Islamic branding, they should understand that the three categories have a common purpose – to balance the trade relationship between the Islamic and non-Islamic world.

Relative to the above categories, Alserhan (2010) says that Islamic branding “dictates that all actions should be divine and that one loves and hates not because of his human desires but because his feelings are in line with Allah’s guidance” (p. 104). To explain this difference further, Alserhan (2010) says that although business relationships in Islamic branding create “earthly” benefits, the parties should pursue them with a divine intent. This way, the material benefits that accrue from pursuing such benefits become divine benefits for all the parties involved. Based on the above differences between conventional branding and Islamic branding, Yusof (2014) says the latter has a greater impetus in the marketing field because it can resonate with its customers better than conventional marketing does.

What does Islamic Branding provide, which is not available Today?

A Faith-based Model for Commerce

Traditional marketing models do not differ much from what we know today as “conventional marketing models.” Both marketing frameworks pursue profit maximization as the main business goal. In this regard, there are few moral or ethical considerations in play. However, Islamic branding introduces a new marketing model that highlights moral and ethical considerations as the main marketing goals. Furthermore, it goes beyond this focus and includes spiritual attributes to marketing campaigns. Therefore, Islamic branding is different from other types of branding because a “pure” motive for doing business drives it (Alserhan, 2010). This “purity” makes it acceptable to believers, regardless of the outcome (profits or losses). The faith-based model is deeper than traditional marketing models because, for Muslims, the concept of “purity” makes simple things, such as washing, breathing, and walking, good deeds (because they appease Allah). Therefore, when Muslims prefer to use halal, instead of non-Muslim products (haram), they enrich their spirituality.

For example, eating healthy foods does not only contribute to living a healthy lifestyle, but also living according to the wishes of Allah. The same is true for all types of products that either have a religious or non-religious connotation to them. For example, if a brand of water is Islam-based, compared to a conventional brand, Muslims are bound to purchase the Islamic brand and neglect the non-Islamic brand. The logic behind this action stems from the contribution of “religious purchases” to one’s good deeds. Nonetheless, it is pertinent to understand that Islamic branding is not only about evaluating if a product is halal or about haram. Nonetheless, many people do not understand that most “worldly” things are halal; however, their uses make them “illegal.” For example, the Quran says, grapes are “holy” fruits (fruits of paradise). However, if people use them to make wines and intoxicate them, they become “illegal.” The same analogy applies to the internet. Virtual communication is a good thing for human societies (halal); however, if people use the platform to distribute pornographic materials, or spread hate, it becomes “illegal.” Islamic branding recognizes non-monetary attributes of marketing and proposes a faith-based model for commerce.

Strong Values

People know Islam for having very strong values that not only span across the religious sphere, but also the commercial sphere. Although most people in the west misunderstand such strong values, The Wire (2008) says it is important for them to understand that Islam constitutes a strong sense of identity that makes it important for people to do things in the “correct” way. When we apply this principle to branding, The Wire (2008) says Islam “defines behavior in a way which makes how you do things as important as the things you do” (p. 2). Most types of branding today do not emphasize the need to merge belief and behavior. For example, western business ideologies often separate religious and business practices. Therefore, it is difficult to find people who do certain business practices because of their religious beliefs, as the primary motivator. However, Islamic branding presents a very narrow gap between belief and behavior. Strong human values narrow this gap.

Strengths of Islamic Branding

Islamic Branding responds to Wider Global Issues Affecting the Muslim Community

It is pertinent to understand that Islamic branding stands to gain acceptance in Muslim and non-Muslim communities because it can promote Islamic ideals at the international and political levels. The Said Business School (2010) believes that this strength is not new because one main objective of Islamic branding is to address issues of negative publicity (directed at the Muslim community). For example, inequality, poverty, extremism, and deprivation are some issues that Islamic branding address. Terrorism is also an important issue that Islamic branding addresses. This marketing model offers an alternative framework for addressing these issues because, unlike popular perception, it does not strive to promote an anti-Western agenda, or an anti-modern agenda.

Several practical examples show how Islamic branding has helped to create a positive perception in the global community (and influence western lifestyles). For example, many people buy coffee (and its products), in the western world, as a popular commodity. However, few people know that the Muslim community introduced this product to Europeans in the 17th century (Said Business School, 2010). At first, many Europeans did not accept it because they said the drink was a product of infidels. However, as time went by, they began to accept it. Today, many people regard it as a desirable commodity, not only in Europe and America, but in other parts of the world as well. To realize the full potential of Islamic branding, it is important to embrace concepts of Islamic entrepreneurship. Unlike other types of entrepreneurship, Islamic branding is an ethics-based model. Moreover, its community-centric ideals make it an effective tool for tackling social injustices that affect the Muslim community. Mass poverty and global injustices are some issues that have received some attention in this regard. Since Islamic branding could influence global issues, it means that it could also affect the lives of non-Muslim consumers, positively. Sustainability issues, global financial crises and the divide between the rich and the poor are some social and economic challenges that Islamic branding could solve in this manner. HE Shaukat Aziz, the former Prime Minister of Pakistan (cited in the Said Business School, 2010) says this strength is a significant contribution of Islamic branding to the global arena because it addresses the social and economic challenges that contribute to some perception problems that most people attribute to the faith. Relative to this fact, Islam could easily bind Muslim and non-Muslims together to create a stronger bond that promotes humanity at different levels.

Since many people consider religion as a taboo in marketing, people should not pursue market segmentation on religious lines. Otherwise, people (especially non-Muslims) may perceive the Islamic branding as a turn-off. The Huntington polarizing model has explained this conflict by warning that promoting faith-based brands may occasionally create conflicts among people of different faiths (Kooijman, 2008). Particularly, the thesis says political differences could easily spill into commercial businesses, thereby creating a clash of ideas (Kooijman, 2008). Although such clashes may often appear in western markets, the Said Business School (2010) believes that Islamic brands, in these regions, stand a better chance of eliminating such clashes.

Weaknesses of Islamic Branding

Lack of Forward Thinking Business Ideals

Undoubtedly, many Islamic businesses stem from the Middle East and other Islamic countries. However, few businesses in these regions have a forward-thinking business acumen that transcends closely-knit social relationships that characterize many Islamic businesses. For example, the Said Business School (2010) says that about 95% of Middle East businesses are family-owned. This ownership structure is not forward thinking because secrets of a business success are usually contained in small social units. Moreover, such ownership structures prefer to promote social units, as opposed to employee merit. Because of such short-term thinking models, the Said Business School (2010) says only about 6% of such Islamic businesses succeed in the third generation of management. Furthermore, only about 2% of these businesses live beyond the sixth generation of managers (Said Business School, 2010).

Muslims are not a Homogenous Entity

Globally, many people perceive Muslims as a homogenous entity. However, this is false. Muslims are a diverse population. Their diversity affects the efficacy of Islamic branding because proponents of the concept have (mainly) built its popularity on the monolithic stereotypes of East-West dichotomies (Said Business School, 2010). However, this homogeneity is unfounded because cultural and lifestyle differences characterize the Muslim market. This diversity makes it difficult for proponents of Islamic branding to develop a common message that all Muslims and non-Muslims could understand. Furthermore, for a brand that is unknown outside Islamic countries, it is difficult to articulate the diversity of the Muslim consumers to the global market. Therefore, Islamic branding suffers a risk of sending mixed messages to the global community.

Threats of Islamic Branding

Perceptual Challenges

The Muslim world suffers from many perceptual challenges regarding its business and commercial activities. The success of Islamic branding depends on how people perceive Islamic businesses because perception affects the market reception of Islamic products. Similarly, it is important for Muslims to perceive their brands positively (as well) because their perceptions affect how they would manage their businesses. In some parts of the Muslim community, people have a negative perception of business and commercial ventures. This negative ideology stems from the idea that business is “worldly”. Kooijman (2008) says the challenge here is to change people’s perceptions of commercial activities. In line with this focus, he says it is prudent to introduce the concept of “business jihad” because people need to see business as a religious goal. Overall, these perceptual challenges make it difficult for Muslims to embrace Islamic branding.

Secularization of States

Social, economic and political activities in the Muslim world keep changing. Some states practice strict interpretations or sharia law, while others practice more liberalized versions of the same. People consider the states, which practice the latter ideology as secular states. Their ideals almost resemble contemporary business practices (usually practiced in the west). The UAE and Egypt are some countries that practice this liberalized business model. Consequently, they have attracted many western commercial interests in their countries. Moreover, western ideologies influence many of their business principles. This fact means that they are transitioning from Islamic business models to conventional business models. This shift leaves very little room for the growth of Islamic branding as the dominant marketing model in such countries. Therefore, their focus on global business practice threatens the growth and sustainability of Islamic branding.

Challenges of Islamic Branding

Unfamiliarity of Islamic Branding

Yusof (2014) says the main challenge of Islamic branding is achieving market success in countries that use conventional (western) marketing models. This challenge arises because non-Muslims often look for different things (non-spiritual benefits) in a marketing campaign. For example, Yusof (2014) says buying products that the Muslim community certifies as halal is important for Muslim customers, but non-Muslims do not share the same attraction because providing a high quality product is more important for them. Similarly, it is difficult to educate people about concepts of Islam, such as halal, if they have no idea what it means. Therefore, the unfamiliarity of Islamic branding is a challenge for the marketing model.

What do Islamic Countries really stand for?

Temporal (2011) says the main problem of Islamic branding is the lack of a definite answer regarding what the Islamic countries stand for. He draws a comparison to western culture by saying that many western countries articulate their branding message. In other words, it is easy to associate certain values, or practices, with specific western countries. For example, people know Germany for its precise engineering. Similarly, people know Italy for is fashion-conscious culture, while, globally, people know Paris for its romance. Such precise branding campaigns do not only exist in western countries because some Asian countries also share the same branding model. For example, the world knows Japan for its technological advancements and its high quality products (like Sony and Toyota). Similarly, the world knows America for its liberties and freedoms. Muslim nations do not have a definitive branding strategy. Stated differently, there is no one thing that most people can point out and associate with the Muslim world. This realization prompted Temporal (2011) to say, “Muslim countries need to assess what they stand for” (p. 18). After doing so, they need to establish a proper brand management strategy that exemplifies their strengths and reduces their weaknesses.

Examples of Islamic Branding

Brunei Darussalam

Islamic branding is the main type of marketing strategy for some Muslim countries. Brunei Darussalam is one country that has adopted this marketing model. The country has a population of about 381,000 people and is located in Southeast Asia (Temporal, 2011). Its government departments mainly use the Islamic branding model to undertake their affairs. For example, the Brunei halal brand is a successful brand campaign that a government ministry started using this model. The Brunei Islamic Religious Council, the Ministry of Religious Affairs, and the Ministry of Health are other government departments that supported this marketing campaign. Islamic branding is part of Brunei Darussalam’s strategy of becoming a global leader in the promotion of halal products. It has specialized in the halal food industry and the catering business (Temporal, 2011). This strategy also complements the country’s goal of economic diversification because its economy depends (heavily) on gas and oil revenues. To diversify, the country strives to invest in tourism and Islamic finance. Islamic branding is at the center of this economic diversification strategy because it promotes three main goals of the national strategy – economic diversification, SME capacity building, and fulfillment of Fardhu Kifayah (Temporal, 2011). Although many Muslim countries share the first two objectives (stated above), the last objective sets Brunei Darussalam apart from them. Fardhu Kifayah highlights the need to have a shared responsibility. It complements Islamic principles on the same philosophy because, as opposed to western commercial ideals, the sharia law demands that the Muslim faithful should pursue their commercial activities for the benefit of the society.

Malaysia

Since Malaysia is largely a Muslim nation, Islamic branding has dominated most aspects of its commercial ventures. For example, its financial market has different versions of Islamic branding. Moreover, western companies that operate in the industry have adopted Islamic branding ideals (Weintraub, 2011). For example, CMIB (among the biggest banks in Malaysia) promotes its products using Islamic branding. HSBC also uses a localized version of Islamic branding because it offers financial products that it exclusively tailors for the Muslim population (Dinnie, 2011). The same is true for Citibank and Standard and Chartered bank (both western companies). However, unlike other Muslim countries that use Islamic branding, many Malaysian businesses use concepts of the marketing strategy that appeal to the mass market.

The UAE

Airline companies and telecommunication companies in the UAE have their roots in Islamic branding. For example, Emirates Airline uses this type of branding. Indeed, it uses Islamic symbolism and calligraphy in its marketing campaigns and (mainly) flies to Islamic destinations (Alihodzic, 2013). It is also a pluralist strategy because it serves alcohol to its customers and sets a uniform dressing code for its airhostesses (Alihodzic, 2013).

Opportunities for Islamic Branding

Harnessing Islamic Ideals and Conventional Ideals

Based on the challenges facing Islamic branding, Yusof (2014) says this marketing strategy could grow by exploiting the opportunities that exist from harnessing Islamic ideals and creating products that appeal to a mass audience (including non-Muslims). For example, brands can mix the emotional and rational characteristics of products with Islamic principles to create products that are more universally acceptable. This strategy would expand the outreach of Islamic brands.

Untapped Muslim Population

Today, the number of Muslims in the world is about 1.8 billion people (Ogilvy-Noor, 2014). This market remains largely untapped because not all Islamic states practice Islamic branding. Since the Halal market today is worth about $2.1 trillion, the value of Islamic branding could expand significantly if this untapped market expanded further (Ogilvy-Noor, 2014). We could draw comparisons to the attention that the Chinese and Indian markets create in today’s global market. Stated differently, Islamic branding experts should be aggressive in exploiting the untapped Muslim market, the same way as global marketers are aggressively targeting the above-mentioned Asian markets. The value for targeting the current and growing Muslim population is about $500 billion per year (Ogilvy-Noor, 2014). Although Dinnie (2011) appreciates the efforts of some marketers in targeting this Muslim population, he believes that managing this market in the long-term will be the greatest challenge.

Targeting Non-Muslims

Although Islamic branding mainly targets the Muslim population, there is a lot of potential for growth if it targeted non-Muslims as well. This recommendation stems from assertions by Temporal (2011), which say that Halal could also appeal to the non-Muslim population. For example, Islamic branding in the food industry encourages people to eat healthy foods. This attribute can also apply to non-Muslims because many people would like to eat healthy foods (not Muslims only). Practical examples also exist in the financial market because Weintraub (2011) says that up to 60% of the financial products marketed through Islamic branding in Malaysia could appeal to the non-Muslim population as well. Similarly, the focus on community welfare in Islamic branding closely appeals to the conventional understanding of corporate social responsibility because they all focus on improving community well-being.

Articulating What Muslim Countries Stand for

Articulating what Muslim countries stand for presents an opportunity for Islamic branding to move to the next level (becoming global). Temporal (2011) says that by doing so, countries that adopt Islamic branding would reap many benefits, including currency stability, restoration of international credibility and investor confidence, attraction of global capital, and growth in exports and branded products. However, the above advantages depend on the ability of Islamic states to create positive perceptions about Islamic brands. Therefore, there is a need to merge the gap between how people perceive Islamic countries and what Islamic branding intends to achieve (Visser, 2009). So far, some Muslim countries are trying to merge this gap. For example, Dubai is slowly cutting out an image for itself as the commercial hub of the Middle East. Similarly, Malaysia is struggling to build a global reputation as the face of “modern Islam” (Temporal, 2011; Fischer, 2008). Interestingly, both countries are competing with each other to gain a favorable reputation among global investors. Based on this fact, Temporal (2011) says these countries are sending mixed messages to the global community about how they should perceive Muslim countries. In fact, Temporal (2011) believes that consistent messages build successful global brands. Inconsistent communications (as shown by Dubai and Malaysia) tend to confuse investors. To complicate further the mixed messaging that comes from Muslim countries; many governments have different agencies that serve different purposes. For example, some government agencies strive to attract more tourists, attract financial investors, and attract expatriates through one communication framework. Although this strategy focuses on achieving several objectives at once, it risks distorting the main picture (to create one common branding for the Muslim world). If these countries realize the potential for doing so, they would create the platform for launching Islamic branding on the global arena.

Summary

This paper shows that Islamic branding is an unexploited marketing concept that could solve many social, economic, and political challenges. The attention that it has gathered shows that this faith-based model provides an alternative framework for promoting goods and services. However, this paper shows that the marketing strategy risks having its credibility eroded through negative media campaigns and strategic failures of Islamic businesses to have a forward thinking business model. Although countries like Dubai and Malaysia have partially embraced this marketing model, Islamic branding could transcend to new levels of success if Muslim countries articulate what they stand for, target non-Muslim markets, and harness Islamic and conventional business ideals.

References

Ahmed, H. (2012). Ethics in Islamic Finance: Looking Beyond Legality. Web.

Alihodzic, V. (2013). Brand Identity Factors: Developing a Successful Islamic Brand. New York, NY: Anchor Academic Publishing.

Alijumani, A., &, Siddiqui, D. (2012). Bases of Islamic Branding In Pakistan: Perceptions or Believes. Interdisciplinary Journal of Contemporary Research in Business, 3(9), 840-847.

Alserhan, B. A. (2010). On Islamic branding: brands as good deeds. Journal of Islamic Marketing, 1(2), 101 – 106.

Azmi, S. (2014). An Islamic Approach to Business Ethics. Web.

Dinnie, K. (2011). City Branding: Theory and Cases. London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Fischer, J. (2008). Proper Islamic Consumption: Shopping Among the Malays in Modern Malaysia. New York, NY: NIAS Press.

Kooijman, J. (2008). Fabricating the Absolute Fake: America in Contemporary Pop Culture. Amsterdam, NE: Amsterdam University Press.

Musa, A. (2013). Islamic Business Ethics & Finance: An Exploratory Study of Islamic Banks in Malaysia. Web.

Obaidullah, M. (2005). Islamic Financial Services. Jedda, SA: Scientific Publishing Centre.

Ogilvy-Noor. (2014). Why Islamic Branding. Web.

Said Business School. (2010). The Inaugural Oxford Global Islamic Branding And Marketing Forum. London, UK: Oxford Business School.

Temporal, P. (2011). Islamic Branding and Marketing: Creating A Global Islamic Business. London, UK: John Wiley & Sons.

The Wire. (2008). Islamic branding: the next big thing? Web.

Visser, H. (2009). Islamic Finance: Principles and Practice. London, UK: Edward Elgar Publishing.

Weintraub, A. (2011). Islam and Popular Culture in Indonesia and Malaysia. London, UK: Routledge.

Yusof, M. (2014). Islamic Branding: The Understanding and Perception. Social and Behavioral Sciences, 130(1), 179 – 185.