Cirque du Soleil is one of the most famous circuses in the world whose shows become a great success in countries the organisation operates in. It is one of the most successful entrepreneurial businesses that expanded globally within only two decades after its establishment. It is also a topic of extensive business research as Cirque’s success is remarkable. For instance, Cirque du Soleil is often described ‘in research as a multi-dimensional creative powerhouse’ (Simon 2015, p. 59). Researchers mainly focus on such aspects as creativity, innovation, leadership and corporate social responsibility when analysing various features of the organisation.

The circus was created in 1984 when its founder, Guy Laliberté, a stilt-walker, an accordion player and a fire-breather started touring throughout Quebec (Moutinho 2016). In 1987, the entrepreneurs decided to go to the USA, and they managed to appear at the Los Angeles Arts Festival with their show We Reinvent the Circus™ (Guy Laliberté, the founder of Cirque du Soleil, on 20/20 2011). This was a great risk as the group invested all their funds into this trip, but it was a great success and the first top they reached. In 1990, Cirque made a show in Europe, and they soon expanded their tour geography to such areas as Asia, South America, Japan, and so on.

In 1993, Cirque du Soleil created their first resident show Mystère® that was shown in Las Vegas. The success of this show led to the creation of other performances in a number of hotels and casinos in the region. At present, the organisation also has shows at Walt Disney World resorts in the US and Japan (Moutinho 2016). The company has won a variety of awards including an Emmy Award. This unprecedented success is a result of hard work, creativity and efficient management as well as the entrepreneurial nature of the business. It is possible to analyse the organisation’s performance and environment using a number of tools such as SWOT tool, Porter’s Five Forces, and Ansoff matrix. This analysis will help to examine the way innovation affects the development of the company (and even an entire industry).

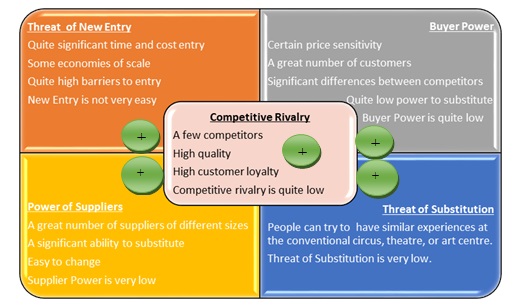

Porter’s Five Forces

The entertainment industry is highly competitive and dependent on entrepreneurs’ creativity. Therefore, the analysis of the organisation’s competitive forces is essential for the understanding of its strengths, competitive advantages and areas to develop to become or remain successful (Magretta 2012). Magretta (2012) notes that the framework is the foundation of any strategy development. A brief analysis of the organisation’s features and its environment shows that Cirque du Soleil is in a very favourable position largely due to its effective use of creativity and entrepreneurial effort (see Figure 1).

As for the threat of new entry aspect, the entry is quite difficult. The shows of such quality can be rather difficult to make due to the need to invest substantial resources (monetary, human, and so on). Cirque du Soleil manages to locate and hire as well as train and develop talent (Gateau & Simon 2016). However, new companies can have difficulties with attracting high-profile employees. It is also necessary to note that the organisation provides various products, including some multimedia items. For instance, the production of reality series, as well as records, is associated with significant gains (Moutinho 2016). As to the barriers to entry, these include little media’s attention to small-scale shows similar to the performance of Cirque and the existence of a variety of regulations concerning human resources management (especially safety issues) (Moutinho 2016). Therefore, it is possible to state that the threat of new entry is insignificant.

Competitive rivalry is another factor contributing to the organisation’s success as there are a few competitors. According to Strittmatter (2011), the most significant competitors of Cirque du Soleil are Live Nation, Six Flags, and Feld Entertainment. However, the author stresses that the four organisations’ shows are quite different. Cirque stands out against the other three due to the creativity and the provision of the blend of circus, dance and performing art, as well as technology (Strittmatter 2011). The quality of Cirque’s shows is very high, which also contributes to their popularity. Thus, the competitive rivalry is not very high.

Porter’s segment concerning the power of buyers is another important aspect to consider. It is clear that buyer power is quite low. The organisation has millions of customers worldwide. Of course, there is certain price sensitivity, but the organisation tries to provide shows that are adjusted to different country’s needs and pockets. The customers are unlikely to switch to other competitors or smaller groups as the quality, as well as the level of creativity, of Cirque’s shows, is very high. Moreover, as has been mentioned above, the number of competitors is rather low (there are only three major competitors), so customers have limited choices. Hence, it is necessary to note that buyer power is quite low.

As far as the threat of substitution is concerned, it is not high. The experiences people have during Cirque du Soleil shows are unique and valued by people (Batson 2016). Of course, people can find similar experiences in different places. They may go to a circus or a theatre, but they will not be able to see the show of that kind in one of those places as those will be fragments of experiences customers gain at Cirque du Soleil. Clearly, substitution threat is very low as there are no other ways to get the same emotions.

Finally, supplier power is also very low. The organisation buys from suppliers of different sizes. For instance, it can buy from multinationals as well as local producers of various materials and technology (Hsiao, Ou & Liu 2013). Besides, the organisation has its own facilities for the production of some of the central resources (costumes), which decreases the power of supplier.

It is clear that Cirque du Soleil has significant competitive advantages. It does not depend on suppliers, and the number of customers is very high. It has the necessary resources to create innovative and unique shows that become popular worldwide. The products provided are nearly impossible to substitute, and there are a few places where people can gain similar (but still different) experiences. The analysis with the use of Porter’s Five Forces shows that the organisation has a competitive advantage and can operate successfully in the market.

Ansoff Matrix Application

Apart from the analysis of the competitive advantage, it is important to consider the products developed and markets aimed at. This information will help to identify the effectiveness of the strategy that is employed (West, Ford & Ibrahim 2015). It is noteworthy that Cirque du Soleil has developed an efficient strategy, as its products are valued by customers in different markets.

Figure 2. Ansoff Matrix.

The chosen strategy involves the focus on product and market development, which are often regarded as the most cost-effective ones (see figure 2). This approach is associated with the need to invest quite significant funds and resources, but such strategies as diversification tend to be associated with significant investment and high risks (West, Ford & Ibrahim 2015). In this case, the risks are comparatively low, which makes the investment cost-effective. It is important to add that the major focus is on the development of new products. Rantisi and Leslie (2014, p. 2) note that Cirque can be regarded as ‘a model of creativity’. The development of something new is the major factor contributing to the organisation’s success throughout its entire history. The founders of Cirque du Soleil have also managed to create different markets as the blend of several types of art (circus, theatre performance, music, dance) was an innovative and even provocative business idea that has proved to be successful.

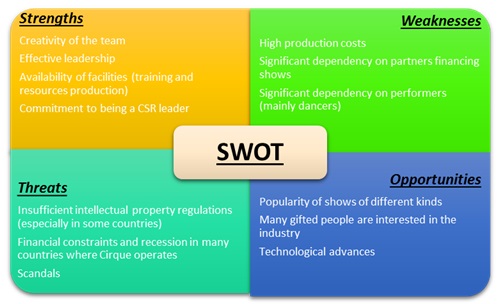

SWOT Analysis

The SWOT analysis is another efficient tool to estimate the effectiveness of the organisation’s potential, areas to improve, opportunities to consider, and possible risks to take into account. Sahinoglu and Yildirm (2016) claim that this framework is instrumental in the assessment of controllable and uncontrollable variables that affect the performance and development of the organisation. The SWOT analysis of Cirque du Soleil’s controllable and uncontrollable variables shows that the organisation has the necessary features to remain a leading company in the industry, but it still has to address certain issues that can undermine its development.

Among the strengths of the organisation, its creativity is the central one (see figure 3). It has been the reason for the prompt and lasting success and viability of the business (Aaker 2012). Of course, creativity is at the core of successful products development. Cirque managed to create shows that have captured viewers’ attention for decades, and they continue surprising and fascinating. Creativity helps the organisation address the issues associated with resources constraints as new costumes and scenery are often produced with the use of quite cheap and used materials (Hsiao, Ou & Liu 2013).

Efficient leadership is another strength of the organisation. Adherence to transformational leadership is an important factor contributing to the company’s success. Clearly, there is a visionary leader, Guy Laliberte, in the organisation, but any member of the team can and does share ideas that are often brought to life. This kind of leadership has also led to the development of the unique organisational culture where failure is a stimulus to evolve, and teamwork is the major commitment of employees (Simon 2015). The availability of facilities where performers train and major materials (costumes and so on) are produced is another strength as the company is not dependent on suppliers. Cirque’s commitment to remaining a corporate citizen is also a significant strength. The company has developed a specific image attracting customers since modern people are concerned about social and environmental issues.

When it comes to weaknesses, the organisation has to address a number of issues. One of the primary weaknesses is the high cost of production (Strittmatter, 2011). This leads to high prices that can be unaffordable for a wide audience. More so, the high production costs put the company into a considerable dependency on external investment. The company relies quite heavily on funds provided by partners and individuals (Guy Laliberté, the founder of Cirque du Soleil, on 20/20 2011). Cirque is dependent on the funds provided by its partners, which can be an issue as the partners may try to affect the organisational culture.

The split profit with partners is a specific issue associated with the reliance on their money. Clearly, the collaboration with numerous leaders in various industries (IBM, Epson, Toyota, Vodafone, Audi, Celebrity Cruises, and so on) is an important factor contributing to the development of the company and its brand (Moutinho 2016). The companies mentioned above are global leaders who have a wide audience of loyal customers who can afford to spend a lot, so this kind of publicity is beneficial for Cirque du Soleil. Nevertheless, Cirque is in a constant search for funding, which can make it too dependent on some partners. Other weaknesses include the overreliance on dancers who are regarded as the core of the show. This approach puts the organisation in a certain dependency on a particular group of people, which may be rather dangerous for the entire company.

At the same time, the company’s opportunities are ample. One of the opportunities is a considerable interest of the audience across the globe to shows of different kinds with special attention paid to dancing and performances (Ghazzawi, Martinelli-Lee & Palladini 2014). Clearly, technology provides a variety of tools and methods to come up with outstanding shows. Cirque has made technology an indispensable part of their shows, which makes them stand out (Leroux 2016). Finally, the company is unlikely to have difficulties with locating and hiring talent as plenty of gifted people are interested in being employed in the entertainment industry. Besides, Circus has an image of a corporate citizen who has favourable working conditions among its portfolio of various CSR activities (Cirque du Soleil – case study 2010).

Nonetheless, the organisation has to pay attention to certain threats to remain a leading company in the industry. One of these threats is the insufficient legislation concerning the protection of intellectual property in the entertainment industry (specifically in such spheres as the circus, street performances, and so on) (Crasson 2012). Potentially, anyone can replicate the company’s shows or elements of these performances, which can make Cirque less unique. As has been mentioned above, tickets prices are quite high, which can pose some threats in the period of recession or in low-income communities and developing countries. Finally, some scandals can be a substantial threat as they can have adverse effects on the company’s image as a CSR leader. The scandal involving Matthew Cusick, who was fired due to his HIV-positive status, still casts a shadow on the company’s ways of treating employees (Coronado 2011).

Irrespective of some weaknesses and threats, it is possible to note that Cirque du Soleil is one of the leading companies in the entertainment industry. This is likely to be that way due to the efficient leadership and management, creativity and the use of technology. Of course, the company should try to address such issues as high production costs and high ticket prices, as well as some legal issues. However, the major strength of the organisation is its focus on innovation, which enables it to remain the leader.

The Use of Blue Ocean Strategy

Many researchers argue that the use of the so-called blue ocean strategy has enabled Cirque du Soleil to succeed in the highly competitive entertainment industry. Prior to addressing this claim, it is necessary to understand what this strategy is. Kim and Mauborgne (2004, p. 2) define blue oceans as ‘all the industries not in existence today’ while red oceans are ‘the known market space’. It is noteworthy that the authors often refer to Cirque du Soleil as an illustration of the use of this strategy. It is also stressed that the method has been in use for decades. For instance, such industries as aviation, management consulting, IT, and many others emerged as blue oceans in the 20th century, but this strategy has become specifically widespread in the 21st century (Malhotra & Seth 2014).

Kim and Mauborgne (2015) note that the contemporary business environment is characterised by the existence of both types of oceans. The authors stress that many companies make quite widespread errors associated with operating in red oceans. The major mistake is the focus on the existing needs of the customer. A simple illustration of the effects of the use of the two strategies can help to identify the benefits of blue ocean strategy. Sony focused on the needs of the existing customers who wanted better legibility of texts, while Amazon Kindle addressed the wants of nonbuyers who wished to have more titles (Kim & Mauborgne 2015). Amazon was the winner of that competition.

Kim and Mauborgne (2014, p. 18) describe the central features of blue ocean strategy that include the creation of the uncontested market space, making any competition irrelevant, the creation and capture of demand, breaking ‘the value-cost trade-off’ and aligning the organisational activities to achieve differentiation and low cost. In simple terms, the basis of the blue ocean strategy is the focus on innovation. Organisations should try to provide services that have not been found anywhere, which will create a new uncontested market space.

This is what Cirque du Soleil managed to do in the mid-1980s. Bessant and Tidd (2015, p. 202) note that Cirque became successful through ‘redefining the circus experience’. There were numerous circus companies, as well as street performers troupes, in the 1980s. Guy Laliberte and members of his group had to address a stiff competition. They chose the most effective strategy (blue ocean strategy) and created a totally new market space that implied the blend of quite different activities. It was a significant innovation to combine elements of circus, theatre and dance hall (Leslie & Rantisi 2016). It was also quite a high risk to make a circus without animals. Nevertheless, this innovative approach proved to be successful. Instead of trying to address the needs of circus goers, Cirque du Soleil introduced a new circus experience.

At that, some researchers note that Cirque du Soleil, as well as other creators of blue oceans, often create new products and services that have questionable value. Thus, Downes and Nunes (2014) stress that Cirque created the circus that charges higher than others but makes shows that it can be interesting to a limited group of people. The authors note that their blue ocean, and many others, are disruptions and can have a negative impact on the development of the market. Nevertheless, the unprecedented popularity of Cirque’s shows is the best evidence of the efficiency of the chosen strategy. The limited group of interested people has expanded to the audience of several million people worldwide, which cannot be regarded as a disruption or an erroneous marketing strategy.

In conclusion, it is necessary to note that blue ocean strategy is the method that implies the focus on innovation and creativity. Instead of inventing new features, it is crucial to invent new markets. Cirque du Soleil can be seen as a conventional illustration of the efficacy of this strategy as their reinvention of circus led to the creation of the multi-million business. They did not provide new aspects of the circus experience, but they came up with a mixture of three different kinds of art. Therefore, it is clear that the use of blue ocean strategy can be beneficial for any business. The most important (and the most difficult) thing is to come up with the innovative ideas that could result in the creation of a totally new and uncontested market.

Reference List

Aaker, DA 2012, ‘With the brand relevance battle and then build competitor barriers’, University of California Press, vol. 54, no. 2, pp. 43-57.

Batson, CR 2016, ‘Les 7 doigts de la main and their cirque: origins, resistances, intimacies’, in LP Leroux & CR Batson (eds), Cirque global: Quebec’s expanding circus boundaries, McGill-Queen’s Press, London, pp. 99-122.

Bessant, J & Tidd, J 2015, Innovation and entrepreneurship, John Wiley & Sons, Chichester.

Cirque du Soleil – case study. 2010. Web.

Coronado, K 2011, ‘Whatever happened to … the HIV-positive acrobat who lost his job?’, The Washington Post. Web.

Crasson, SJ 2012, ‘The limited protections of intellectual property law for the variety arts: protecting Zacchini, Houdini, and Cirque du Soleil’, Villanova Sports & Entertainment Law Journal, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 73-133.

Downes, L & Nunes, P 2014, Big bang disruption: strategy in the age of devastating innovation, Penguin, New York.

Gateau, T & Simon, L 2016, ‘Clown scouting and casting at the Cirque du Soleil: designing boundary practices for talent development and knowledge creation’, International Journal of Innovation Management, vol. 20, no. 4, pp. 1-31.

Ghazzawi, IA, Martinelli-Lee, T & Palladini, M 2014, ‘Cirque du Soleil: an innovative culture of entertainment’, Allied Academies International Conference. International Academy for Case Studies. Proceedings, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 15-17.

Guy Laliberté, the founder of Cirque du Soleil, 2011. Web.

Hsiao, RL, Ou, SH & Liu, M 2013, ‘ Creative construction of resources under constraints in the case of Cirque du Soleil’, Technology Innovation Management Review, vol. 2013, no. 1, pp. 675-676.

Kim, WC & Mauborgne, R 2004, ‘Blue ocean strategy’, Harvard Business Review, Web.

Kim, WC & Mauborgne, R 2014, Blue ocean strategy, expanded edition: how to create uncontested market space and make the competition irrelevant, Harvard Business Review Press, Boston.

Kim, WC & Mauborgne, R 2015, ‘Red ocean traps’, Harvard Business Review, Web.

Leroux, LP 2016, ‘Epilogue: circus reinvested’, in LP Leroux & CR Batson (eds), Cirque global: Quebec’s expanding circus boundaries, McGill-Queen’s Press, London, pp. 284-294.

Leslie, D & Rantisi, NM 2016, ‘Creativity and place in the evolution of a cultural industry” the case of Cirque du Soleil’, in LP Leroux & CR Batson (eds), Cirque global: Quebec’s expanding circus boundaries, McGill-Queen’s Press, London, pp. 223-240.

Magretta, J 2012, Understanding Michael Porter: the essential guide to competition and strategy, Harvard Business Press, Boston.

Malhotra, D & Seth, S 2014, ‘The rise of blue ocean strategy and leadership’, The International Journal of Business & Management, vol. 2, no. 9, pp. 248-253.

Moutinho, L 2016, Worldwide casebook in marketing management, World Scientific, London.

Rantisi, N & Leslie, D 2014, ‘Circus in action: exploring the role of a translation zone in the Cirque du Soleil’s creative practices’, Economic Geography, vol. 91, no. 2, pp. 147-164.

Sahinoglu, DZB & Yildirm, F 2016, ‘Entertainment: the new era in lateral thinking -issues and competing trends in retailing’, in RG Ozturk (ed), Handbook of research on the impact of culture and society on the entertainment industry, IGI Global, Hershey, pp. 332-350.

Simon, L 2015, ‘Setting the stage for collaborative creative leadership at Cirque du Soleil’, Technology Innovation Management Review, vol. 5, no. 7, pp. 59-65.

Strittmatter, L 2011, ‘The big top that wasn’t big enough: the case of Cirque du Soleil‘, Journal of International Management. Web.

West, D, Ford, J & Ibrahim, E 2015, Strategic marketing: creative competitive advantage, Oxford University Press, Oxford.