Introduction

In the United States, the strategy has mostly been ineffective in reducing drug abuse and trafficking. Instead, the American War on Drugs had a number of unforeseen consequences, including the enormous incarceration of drug offenders who were not violent and the continuation of racial imbalances in the criminal justice system. Despite the significant resources and efforts that local and federal governments have taken to stop drug abuse in the United States, the War on drugs has ended in failure.

Course of Drug War

Nixon’s Government

The fight against drugs began during the Nixon administration. In 1971, Nixon dramatically increased the staff and budgets of federal law enforcement agencies aimed at combating the import and distribution of substances into the United States (Drake et al., 2020). In 1972, after temporarily including cannabis in the first category of the drug list, Nixon immediately ordered the creation of a commission to review its legal status (Yu et al., 2020). He appointed Republican Governor of Pennsylvania Ronald Shaffer to head this commission. The results of his work had to wait almost a year.

The Commission unanimously recommended that Nixon decriminalize the possession and distribution of cannabis for personal use. Nixon ignored the recommendation, and his manual commission had no choice but to finally include cannabis in the first category of the List of Prohibited Substances (Drake et al., 2020). Such qualifications made it the main target of hunting for special services. When cannabis was given the status of a narcotic substance that promotes rapid addiction, law enforcement officers felt like the arbiters of fate with impunity.

The Black and Latin American population of the United States still suffers from bias in the imposition of cumulative sentences for minimum terms. Currently, out of 111 Americans, one is serving time in federal, state, or county prisons (Cooper et al., 2020). America is ahead of the whole world in terms of the number of prisoners, more than half of whom are serving sentences for crimes related to psychoactive substances.

Reagan’s Government

Under Ronald Reagan’s administration, the expansion of powers and the increase in funds of law enforcement agencies that dealt with the use and storage of substances was carried out at an unprecedented speed. In 1980, when Ronald Reagan came to the White House, there were 50,000 prisoners in US prisons who were convicted of nonviolent drug crimes (Earp et al., 2021). By 1997, the number of the above-mentioned prisoners reached more than 400 thousand (Earp et al., 2021). In 1981, Nancy Reagan launched the Just Say NO campaign, which the media was required to advertise and promote in schools (Yu et al., 2020). This opened the way for the so-called zero-tolerance policy.

In parallel with the zero-tolerance policy for drugs, an anti-drug education program was introduced in schools. The author of this program turned out to be the owner of a remarkable mind and part-time Los Angeles Police Chief Daryl Graves (Drake et al., 2020). Graves was sincerely convinced that all drug addicts should be brought to criminal responsibility (Yu et al., 2020). Despite the fact that this program had no evidence base, it became mandatory in all US schools.

The growing hysteria, spurred by the adoption of relevant laws, led to the imposition of a ban on syringe replacement programs. This has led to the spread of HIV infections (Cooper et al., 2020). 25-30 percent of cases of this disease in America are due to prohibitive measures (Cooper et al., 2020). The ban on financing such programs has shown the ineffectiveness of the policy of struggle adopted in the United States already at this stage.

Clinton’s Government

During his election campaign, Bill Clinton promoted the thesis that drug addicts should be treated, not imprisoned. However, as soon as he took office, the escalation of the war on drugs continued (Drake et al., 2020). He took an equally controversial position on the issue of racial discrimination in sentencing.

When the US Sentencing Committee proposed to eliminate the discrepancy between criminal liability for crack and cocaine, Clinton rejected the arguments of the commission and insisted on tougher measures against crack (Yu et al., 2020). As a result, among drug addicts, the death rate from a crack overdose was less than 10 percent, and from HIV infection – almost 30 percent (Drake et al., 2020). This was due to the fact that Clinton also supported a federal ban on syringe replacement programs, which spurred another round of HIV infection among crack users taking it intravenously.

Bush’s Government

Under George W. Bush, the war on drugs continued in an escalating straight line. It was under Bush that drug policy advisers unleashed a comprehensive drug testing program for students. However, despite the methods, the number of overdose deaths continued to grow rapidly. By the end of the Bush administration, more than 40 thousand raids by police special forces fell on the heads of ordinary Americans, mainly for nonviolent drug crimes, which, most often, turned out to be minor offenses (Drake et al., 2020). Although Obama, in favor of sentencing reforms, did lift the federal ban on funding syringe replacement programs, funding for the war on drugs continues to grow.

Concept of Reducing Drug Use

In the context of this work, it is essential to grasp the meaning of the concept of reducing drug use. Despite the billions of dollars spent annually on the treatment and prevention of drug addiction, overdose is still the leading cause of accidental death in the United States. On average, 44 thousand people die from an overdose of surfactants (Yu et al., 2020). The largest part of these overdoses relates to prescription medications — about 26 thousand deaths, of which 19 thousand are opioid painkillers and 7 thousand are benzodiazepines (Drake et al., 2020). Among the banned substances, about 5,500 people regularly die from cocaine overdose and 11,000 from heroin (Cooper et al., 2020).

The Department of the Drug Addiction and Mental Disorders Treatment Service conducted a survey. It concluded that 90 percent of people who need rehabilitation and treatment for drug addiction practically do not receive such assistance (Yu et al., 2020). Among those to whom this help still reaches, only 30 percent recover (Earp et al., 2021). The centers receiving state funding often have illiterate management, which uses outdated and ineffective methods of treatment.

Reasons for Drug War Failure

As a rule, the annual death rate from cannabis overdose is zero percent. However, at the same time, millions of dollars intended for the prevention and treatment of drug addiction are spent on cannabis consumers. Approximately 17 percent of the total number of patients in government-funded rehabilitation centers are so-called cannabis addicts (Earp et al., 2021). The majority of those found to be abusing cannabis are people whom judges put before a choice: either treatment or prison (Cooper et al., 2020). The very idea of spending a lot of effort and money on litigation with a referral to be treated for a substance that has the lowest level of addiction (9 percent) and overdose mortality seems wasteful and thoughtless.

If the efforts and resources spent really protected the population from overdose and drug-related violence, then such zeal could be called a victory.

Nevertheless, in 2016, a statement from a 22-year-old interview with former Nixon aide and domestic policy adviser John Ehrlichman was published (Yu et al., 2020). In it, he argued that the war on drugs had nothing to do with the fight against drug addiction (Cooper et al., 2020). It was claimed that the presidential administration deliberately used this campaign as a screen to fight the left-wing anti-war movement and the desire of the black population of America to defend their rights.

The war on drugs in its current form is doomed to failure. There are a huge number of graphical indicators indicating that the number of drug addicts has not decreased at all since the declaration of war on drugs in 1971 (Earp et al., 2021). $1.5 trillion spent on combating fatal overdoses, terrible drug addiction, and the violence that accompanied the illegal trade did not lead to an improvement in the situation (Yu et al., 2020). Overdoses have not disappeared, the growth in the number of people who have become drug addicts has not decreased, and the illegal world trade in prohibited substances has only fueled the fire of violence. The adopted policy did not bring the expected results and did not even bring them closer.

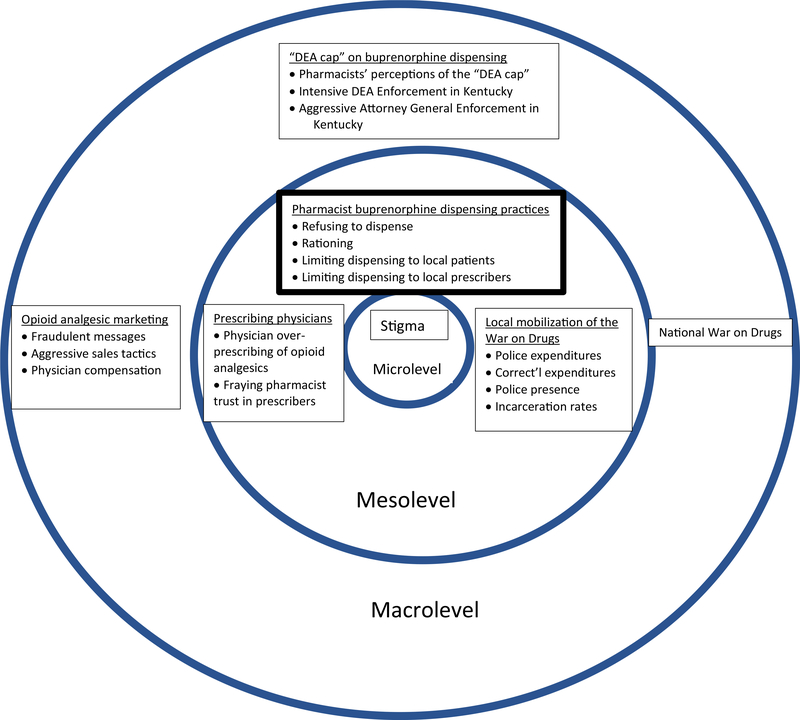

From the point of view of the Nixon administration found a simple solution to a difficult task. However, as can be seen from Figure 1, the national war on drugs was only part of the overall picture of how substances functioned in American society. The progressive forces of the late 60s and early 70s were rapidly gaining political weight, and the White House, in the shortest possible time, needed to establish control over them (Earp et al., 2021). Therefore, troublemakers were publicly associated with drugs. Moreover, on charges of using substances that allegedly lead them into an aggressive state, such subjects can be arrested en masse and, by their example, discredit the entire movement as a whole.

Understanding the motivation behind declaring a crusade against drugs is more relevant today than ever. Two out of three Americans are sure that people should not be involved in possession of heroin, cocaine, and cannabis (Yu et al., 2020). A survey conducted in 2018 showed that the majority of Americans want an end to this war, but the laws underlying such a policy continue to operate (Earp et al., 2021). They are used to prosecute, prosecute, and detain substance users. As a result, the defenders of legalization have to wait behind bars when federal policy will take into account public opinion.

Conclusion

Thus, the fight against drugs in the United States has proved to be ineffective. This happened as a result of the fact that it was not a measure for stopping drug abuse but an excuse to arrest those who disagree with the government’s policy and silence them. The perception of drug addicts not as sick but as criminal criminals has made the campaign against drugs unsuccessful, and it continues to be a failure to this day.

References

Cooper, H. L., Cloud, D. H., Freeman, P. R., Fadanelli, B. S., Green, T., Meter, S. V., Beane, S., Ibragimov, U., & Young, A. M. (2020). Buprenorphine dispensing in an epicenter of the U.S. opioid epidemic: A case study of the rural risk environment in Appalachian Kentucky. International Journal of Drug Policy, 85(102701), 82-87. Web.

Drake, J., Charles, C., Bourgeois, J. W., Daniel, E. S., & Kwende, M. (2020). Exploring the impact of the opioid epidemic in Black and Hispanic communities in the United States. Drug Science, Policy and Law, 0, 1-11. Web.

Earp, B. D., Lewis, J., & Hart, C. L. (2021). Racial justice requires ending the war on drugs. The American Journal of Bioethics, 21(4), 4-19. Web.

Yu, B., Chen, X., Chen, X., & Yan, H. (2020). Marijuana legalization and historical trends in marijuana use among US residents aged 12–25: Results from the 1979–2016 National Survey on drug use and health. BMC Public Health, 20(156), 102-126. Web.