When people hear of the South Pacific, pictures of balmy equatorial islands come to mind first. However, the islands of Oceania encompass a much wider range of habitats. It ranges from the Australian deserts to New Guinea’s tropical forests to the Marshall Islands’ coral atolls. Overall, the region is not only geographically diverse but also varies culturally, politically, linguistically, and artistically.

Due to the expansive colonization beginning in the 16th century and peaking in the 19th, the West took an interest in these island groups. Consequently, much of Oceania’s history in the 20th century is centered around the natives’ struggle for independence from the colonial powers (Kleiner, 2016b).

Nevertheless, colonialism also made an exchange of ideas possible — it was not a sole one-way transfer of Western technology and cultural values to the Pacific (Kleiner, 2016a). Oceanic art, for instance, strongly impacted many Western artists, Paul Gauguin among them (Atkin, 2018). On a broader scale, the “primitive” Oceanian art influenced the early-20th-century artistic movement of surrealism by its poetic and even “magical” vision.

Traditional Oceanian Art

Oceania is divided geographically into the areas of Australia, Melanesia or black islands, Micronesia or small islands, and Polynesia or many islands. Melanesia consists of New Guinea, New Britain, New Ireland, New Caledonia, the Solomon Islands, the Admiralty Islands, and other smaller groups. Micronesia in the western Pacific includes the Mariana, Caroline, Marshall, and the Gilbert Islands. Lastly, Polynesia covers the eastern Pacific, with the Hawaiian Islands situated in the north, Rapa Nui (also referred to as Easter Island) in the east, and, finally, New Zealand being in the southwest.

Australia

In Australia, the Aboriginal world’s perception centers around the concept of the Dreamings – ancestral spiritual beings pervading the present. Aborigines identify particular Dreamings as their totemic ancestors responsible for creating physical space and landscape and turn to them for religious, cultural, and moral guidance (Kleiner, 2016a). Due to the significance of Dreamings to all Aboriginal life aspects, native Australian art connects Aborigines with ancestral beings in a symbolic fashion.

Various art forms, such as carved figures, body painting, sacred objects, decorated stones, and bark and rock painting, serve as essential means of their expression. Being predominantly gatherers and hunters in severe environments, the Aborigines, in general, were nomadic; thus, monumental art proved impractical, causing most Aboriginal pieces of art to be portable and relatively small. The artworks showcase an X-ray style, which Aboriginal artists used to illustrate human and animal forms (Figure 1). In this style, the painter simultaneously depicts the exterior appearance and internal organs of the subject.

Melanesia (New Guinea)

Typical Melanesian cultures are relatively democratic and unstratified: existing political power usually belongs to groups of older men and, in some areas, older women who communally manage the people’s affairs. Among these groups, locally distinct individuals (Big Men) renowned for their political, economic, and, in the past, warrior skills can accrue power (Kleiner, 2016a). Because power and rank in Melanesia are within certain limits earnable, multiple cultural practices, such as rituals and cults, are centered around obtaining knowledge that allows advancing in society.

In order to represent and acknowledge the advancement, Melanesian societies conduct elaborate festivals, build communal meetinghouses, and create art objects. For example, the Asmat people of the southwestern coast of New Guinea practiced headhunting and built bisj poles as pledges to avenge their fallen relatives (Figure 2). Overall, these cultural compositions serve to support the social order, maintaining social stability.

Microneisia (Caroline islands)

The Austronesian-speaking societies of Micronesia have a much more strict social stratification than the ones in New Guinea and other Melanesian islands. Micronesian cultures often center on chieftainships; their craft, ritual specializations, and religions include both honored ancestors and named deities. Life in nearly all Micronesian cultures concentrates on maritime activities, such as fishing, trading, and long-distance travel with the use of large oceangoing vessels (Kleiner, 2016a).

For this reason, much of the Micronesian artistic imagery is associated with the sea. For instance, it is unsurprising that the most highly skilled artists from the Caroline Islands predominantly were masters in canoe building. The canoe prow ornament depicted in Figure 3 comes from the Chuuk people. Carved from a wood plank and fastened to a paddled war canoe, the prow ornament ensured protection on challenging or long voyages. The fact that prow ornaments represent not permanent canoes’ parts mirrors their function. When approaching another canoe or vessel, the Micronesian seafarers could lower the ornaments, signaling that their voyage was peaceful.

Polyneisia (Easter island)

Polynesia was one of the world’s last areas where humans settled. Residence in western Polynesia began near the end of the first millennium BC, whereas in the south only in the first millennium AD (Kleiner, 2016a). The settlers brought complex religious and sociopolitical institutions with them.

While Melanesian societies are relatively egalitarian and in-rank advancement is possible, Polynesian societies generally are highly stratified, with heredity determining the power. The origins of their rulers are traceable “directly” to the gods of creation. Most Polynesian societies have elaborate political organizations ruled by ritual specialists and chiefs. By the 19th century, some Polynesian cultures, such as Hawaii and the Society Islands, became kingdoms (Kleiner, 2016a).

Historically, because of strict social hierarchy, most Polynesian arts belonged to noble or highly-ranked religious individuals, serving to support their prestige and power. It was believed that these art pieces, like their owners, possessed great spiritual power. For instance, moai found on the Easter island were thought to accommodate spirits or gods (Figure 4). Thus, they mediated between chiefs and the latter and between physical and spiritual worlds.

European Surrealism

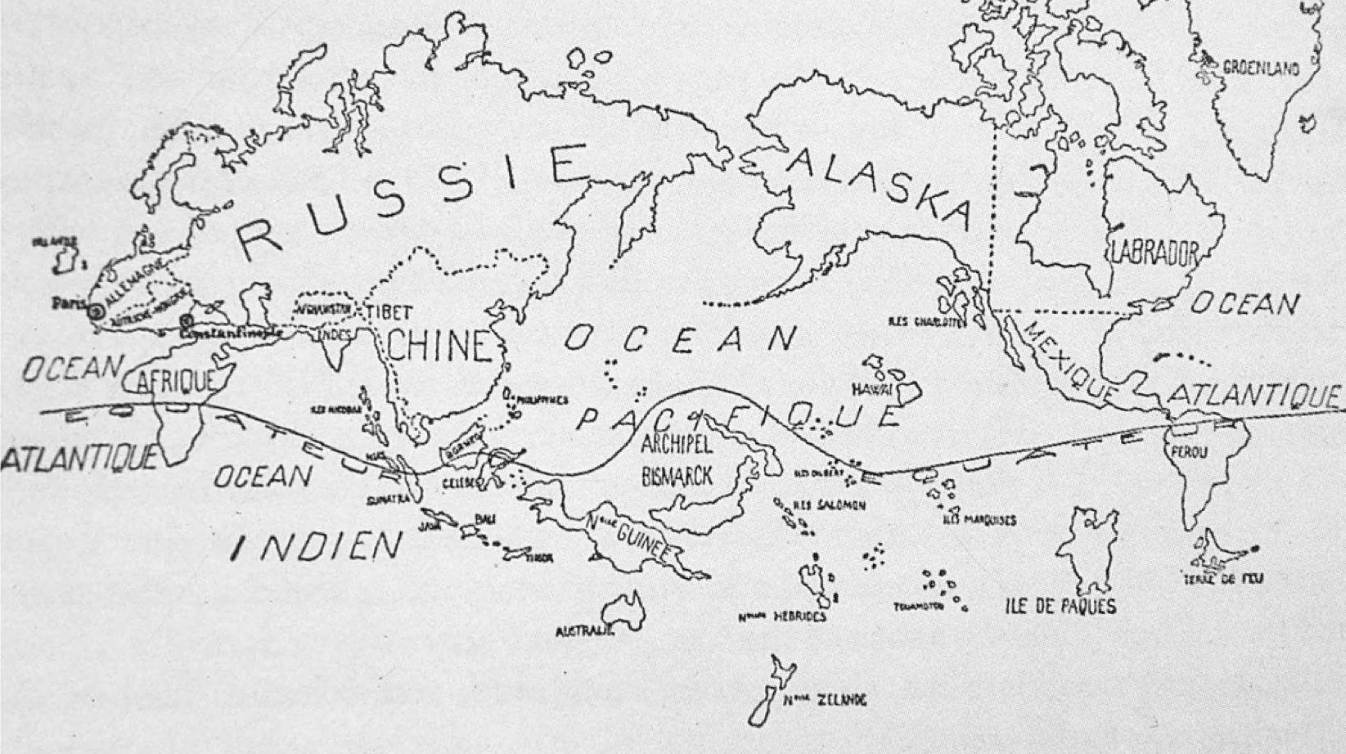

Unfortunately, many traditional artistic features of Oceanian cultures ceased due to the European colonial influence. In this regard, Aborigenal art received a lot of support from various sources, especially from surrealists of early 20th century (Atkin, 2018). Figure 5 pictures the surrealists’ vision of the world from the perspective of artistical contribution each country and continent made to society. Most notably, the colonial powers, such as France or the U.S., are greatly underrepresented, while Oceania is put in the center, being the greatest in size. It implies that surrealism as a movement had its reasons to display such attitude toward the “developed” societies.

Born of an intellectual protest against World War One, surrealism was uniquely tied to the idea of an acute revolution against western modernity. At this point in the history of the surrealism movement, Pacific art began to acquire new significance for surrealists as a “magical” revolution template.

In this context, the “magic” took a more specific form behind the surrealist concept of “magic culture,” which deemed Pacific art a guide to experience the world anew (Atkin, 2018). The utterly alien patterns and motifs of Melanesian, Polynesian, and Micronesian cultures did not simply represent different abstract or figurative imaging modes for the surrealists. Instead, they displayed an entirely new semiotic relationship order.

The works of Gauguin who spent the last years of his life in the Pacific are filled with this “new” symbolism. Gauguin’s philosophy can be described by one of his favorite citations, stating that “[t]he artist will interest us less by a vision tyrannically imposed and circumscribed, however harmonious it may be, than by the power of suggestion that is capable of aiding the flight of the imagination or of serving as the decorator of our own dreams, opening a new door onto the infinite and the mystery of things” (Atkin, 2018). It is this idea of the mystery of things, that a surrealist would call “magic” and a critic “primitivism.”

Thus, surrealists correlated the colonial struggle of the “uncivilized” native against the “civilized” European with an ideological battle between a “primitive” thinking mode and “rational” western thought. However, it was sophistication, not simplicity, that the surrealists desired from the “magical” nature of Oceanic visual culture (Atkin, 2018). It was also an effective remedy, not retrospective historical escapism, that they sought for the most pressing concerns in the face of post-war civilization (Atkin, 2018).

Therefore, it becomes evident how the surrealists’ intensified propaganda of “magical” thought directly correlated with their anti-colonial attitudes. It was conceived to combat the official scientific rationalism that had indirectly enabled and now supported colonial politics (Atkin, 2018). Consequently, after being entirely convinced of the politics’ futility due to the diplomatic catastrophe that caused World War Two, the surrealists made a collective shift toward “magic” as an alternative to changing the world.

Conclusion

In its remarkable variety and “primitivity,” traditional Oceanian art managed to impress and guide the surrealistic revolutionary school of European art. Based on the choice of the archipelago, ranging from X-ray bark paintings of Australia to vengeful bisj poles of New Guinea to Carolinian ornamented canoes to monumental moai of Easter Island, Oceanian art varies but manages to maintain the idea of technologically “unspoiled” vision. This vision surrealists used to draw inspiration from, and contra posed it to the accepted civilizational status quo in their attempt to start a revolution inside people’s hearts.

References

Aldrige, R. (n.d.). Oceanic art. New Guinea tribal arts. Web.

Atkin, W. (2018). Oceanic metamorphoses: Easter Island, Paul Gauguin and “magic art” through the eyes of the surrealists.Journal of Postcolonial Writing, 54(5), 670-689. Web.

Kleiner, F. S. (2016a). Gardner’s art through the ages, book C: Non-Western art to 1300 (15th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Kleiner, F. S. (2016b). Gardner’s art through the ages, book F: Non-Western art since 1300 (15th ed.). Cengage Learning.

Appendix