Introduction

Dreams are considered by psychologists as a way through which the human body overcomes both mental and physical challenges. The psychology of dreams in human beings is an aspect that has been studied for ages now since the onset of the 19th century. Among key psychologists that have examined dreams in human beings are Sigmund Freud and Jung C.G. These two attribute the occurrence of traumatic events in dreams to past fears or previous traumatic exposures. The current study is based on the findings of a previous field study on two groups of children in Palestine. In this study, the concepts of dreams as presented by Sigmund and Jung and their application on Trauma and Dream content will be evaluated. The article by Valli et al. (2006), depicting a field study on children in Palestine is the basis of the current study. The original study was a case control study in which children presenting with past traumatic experiences were matched to those presenting without past traumatic experiences and their dream contents compared. The children used in this study were randomly drawn from two distinct regions in Palestine that is, the Gaza strip and Galilee. The main objective of this study was to test a number of hypotheses and predictions emerging from the Threat simulation theory (Punamaki et al., 2005). Among the obvious objectives was to examine the impact of exposure to military activities such as gun shots on the psychology on children. With reference to the threat simulation theory, it is postulated that experiences in real life should induce the response to the simulation of threats if the role of dreams is to simulate any threats (Revonsuo, 2000). Therefore for the children in the Gaza strip, their experiences in real life with various military activities should possibly have an influence on their dream contents.

Hypotheses

When comparing the contents of the dreams in the two groups of children, it is expected that:

- Dreams of previously traumatized children will more often point to threatening experiences as opposed to the dreams of children without any previous traumatic experiences. This is with regard to the fact that the dreams of traumatized children are stimulated by real threats which impact on their threat induction system.

- Since dreams are induced by real threats, it is thus expected that previously traumatized children will experience more dreams than their peers in the control group that is, children drawn from a rather peaceful setting.

- In traumatized children, the efficiency of threat simulation depends on the parties common to the dream or rather the dream self. This implies that unlike in non traumatized children, the items significant to a dream are more threatened in the dreams of previously traumatized children than in children from peaceful backgrounds.

- Unlike in children that do not have previous traumatic experiences, the threats common to the children with traumatic experiences happen to be of a greater degree of threat or are more threatening when viewed in a real life perspective.

- The simulation of the threat is thought to be rampant in the event that a presumed threat is immediately followed by an attempt to avoid the threatening situation. This implies that the dream self reacts more frequently to the threatening situation in traumatized children than in children presenting without previous traumatic experiences.

- It is also postulated that the reaction of the dream self positively correlates to the severity of the threat.

Methodology

This study is based on the findings of a previously conducted field study in Palestine in the year 1993. The main source of data is thus the findings depicted in this study that will be subjected to retrospective analysis. In the study, the Threat Simulation theory was used while focusing on the events that occur following an exposure to trauma while in sleep. In the original study, the participating subjects were each offered a diary which was used to take note of all the events that transpired while in their sleep (Valli et al., 2006). The children and adolescents included in the study were randomly selected and given instructions on how to fill in their dairies. Consent for participation in the study was obtained from both the parents and the children. The dairies were filled in Arabic languages and the contents were later translated into English by analyzers. Illiterate children relied on their mothers to fill in their dairies for them after narrating their experiences to their mothers every morning. This data was then handed to observers at the end of a week. The data was then subjected to analysis by two judges who classified it into two categories (Valli et al., 2006). In the first category also referred to as the Objective Threat, either the physical or mental state of the subject is endangered in a dream. The second category also called the Subjective Threat was such that an event experienced in a dream is presumed to be dangerous. Each of the dreams experienced by the subjects was also classified into its own category. Among the categories in which the analyzers classified the dreams were; with regard to the threat, the severity of that threat and the reaction of the self to the threat.

Sample Size Determination

In the original study, sample size determination was guided by the purpose of the study. A relatively large sample was used in order to allow for a better comparison between groups. The large sample size was equally important in order to obtain a significant statistical power. The study was conducted on 413 subjects comprising of children and adolescents randomly sampled from Galilee and Gaza.

The Study Population

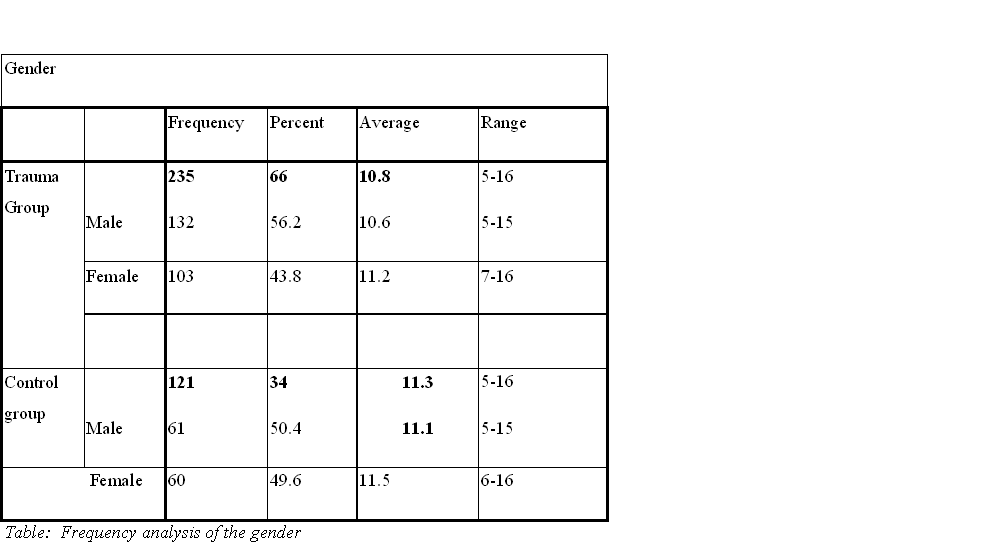

From the study population, 269 of the participants were drawn from the Gaza strip while 144 were drawn from Galilee. The two regions are distinct in that Gaza has been exposed to various uprisings while Galilee enjoys a peaceful life. The children drawn from Gaza were thus labeled as the Traumatized group while those drawn from Galilee were classified as the peaceful or non traumatized group. The first group of children also called the trauma group had 235 subjects with the control group made up of 121 subjects (Valli et al., 2006). From the original study population, 34 children from the first group and another 33 from the second group were excluded from participation for lack of dream related experiences. The children excluded in the study also happened to be relatively older than those that were included in the study. The distribution of the population by gender is as depicted in the table below.

Data Collection

In the original study, a dream was described as an experience during sleep which can be complex, subjective and at times progressing temporary. With this definition, real dream experiences were clearly distinguished from other experiences that could not qualify as dreams. The reports as filled in the diaries were collected from the subjects and subjected to analysis. For reports that were not narrated which were subsequently excluded from further analyses, only the dream’s topic was mentioned (Valli et al., 2006). For the population included in the study, 25 and 47 non narrative reports from the trauma and the non trauma groups respectively were noted and thus not subjected to further analysis. The rest of the reports were then analyzed with regard to the inherent threat. Initially the threats as pointed to in dream narrations were categorized on the basis of the content of the dream.

The identification and the classification were conducted by two judges working independently. This was later subjected to a common rating to attain some common agreement. As previously mentioned, threats were classified as either objective or subjective. For effective rating of the reports, the dream reports from the subjects in the study were mixed with those from a previously conducted study on Kurdish children and rated blindly. Any ambiguities were excluded in the study in order to support the hypotheses. The threats as depicted in the dream reports were later categorized with regard to the target, the severity and the reaction to the event. To foster a common rating standard, any disagreements among the raters were subjected to a joint discussion until a common agreement was attained (Valli et al., 2005).

Statistical Analysis

Analysis of the generated data was done using SPSS 10.0. Differences between groups were compared using a non parametric test while using the group medians. The frequency distribution for the threatening events between groups were compared using a Pearson’s Chi-test. In order to avoid the tendency of type II errors, unequally distributed data was logarithmically normalized.

Results

In summary, children in the trauma group depicted results that were significantly higher with reference to almost all of the quantitative variables compared to their peers in the non trauma group. The results were in favour of the hypothesis that the children in the trauma group had more dreams than their peers in the control group. The number of threatening events also differed significantly between groups as was indicated by U=10432.5 and U=9555.0 for the number of threats and the number of dreams respectively among the trauma group. With regard to the target of the threats, the results indicated that the self in the non trauma group was the most threatened than was the self in the trauma group (Valli et al., 2006). When the nature of the threats was compared, it was evident that children in the trauma group experienced more severe threats in their dreams than those in the control group. With regard to the reaction to the threat, the two study groups were compared on the basis of who specifically reacts to the threat. The results showed no significance differences between groups.

Background of the Study

Various studies on the causes of traumatic experiences in dreams have previously been major topics of discussion among psychologists. In all aspects, it emerges that dreams are experiences common to all people (Punamaki et al., 2005). However Freud indicated that all dreams have their own distinct significance and impacts. He further indicated that an understanding of dreams requires a clear understanding of the predetermining experiences (Eng et al., 2005). With very many theories geared at explaining the significance of dreams, most psychologists indicate that dreams are meant to allow the dreamer to address the threats or fears pointed to in their dreams (Cartwright, 2006). According to Freud, the unconscious state of the mind happens to be submerged but also very enormous. He adds on to say that all dreams have a meaning irrespective of how they occur. According to Wade and Tarvis (2008), the trauma impact on the dream tends to awaken the dreamer as they plunge into consciousness. This aspect basically implies that a dreamer is likely to be awakened by the severity of the threat in the dream. There are situations in which dreams are regarded as situations through which people encounter problems (Villalba et al., 2007). However, trauma is an aspect that tends to accompany individuals at varying times and different individuals have varying ways of dealing with it (Adler-Nevo et al., 2005). Some people have evolved mechanisms of dealing with trauma while others do not have such mechanisms.

Traumatic events that arise in dreams are as a result of the memory retained following the encounter of the event in real life situations (Gaffney, 2006). Jung’s perspective of dreams as a collection of memories in the subconscious mind of a human being is important in explaining the implication of dreams (Wade & Tarvis, 2008). This perspective was narrowed down into several categories with regard to the persona, the shadow, the animal, the divine child, the wise old man or woman, the great mother and the trickster. This perspective has a very strong impact in the study of dreams in children (Gaffney, 2006). According to Jung, young children are more likely to give an account of events as they occurred and may possibly exaggerate in order to make it easier to understand and possibly interesting (Kuiken et al., 2006). Further studies have also indicated that very many children have a tendency of narrating things that did not happen. This possibly explains the need to critically distinguish between real dream experiences and non dream related experiences.

Conclusion

In the original study, the children in the trauma group had been previously exposed to traumatic events following uprising in Gaza unlike their peers in Galilee which happens to be rather peaceful. The subjects in the study never left their homes during the study period in order to avoid subjecting them to other varying conditions. Though the study indicated significant differences in the two groups with regard to the variables examined, a better study design based on the children in Galilee alone would have been more appropriate. These children would possibly have been put under traumatic conditions for some time and later had their dream contents examined. Though it has been proved that dreams are common to all people, further research was highly needed to establish if real life experiences have any significant impact on the occurrence of dreams which formed the basis of the field study in Palestinian Children. Insights in to the basis of dreams have been highly driven by theories indicated by Freud and Jung despite the fact that these theories are yet to receive worldwide acceptance.

The psychoanalysis by Freud is an indication that dreams have meanings and that encounters in the conscious state of the mind can as well be encountered in the subconscious state during dreams. Jung’s theory was almost similar to Freud’s theory with the seven categories depicting the most likely experience that an individual may have in a dream. However both of these theories were lacking any concrete evidence that would have allowed them to possibly gain acceptance. The two theories are still vital in the study of the impact on trauma on the content of dreams. With regard to the results depicted in the case study, the two theories need further testing and evaluation coupled with evidence based findings to foster their applicability and acceptance. The field study in this paper points out an ideal illustration of how a hypothesis or theory can be tested. With regard to the study population, it was easy to state and proof that children in troubled regions such as those from Gaza are more likely to be subjected to lots of traumatic experiences which have an impact on their dream content. This is as opposed to children in relatively peaceful settings such as those in Galilee. These findings in this study have a strong implication to help assert that indeed trauma has an effect on people’s dreams. The study done on the children of Palestine is equally an ideal illustration of how researchers can distinguish dreams from non dream experiences. Though the theories pointed to by both Jung and Freud are vital to the understanding of dreams, more studies in the future should help proof if the dream theory illustrated by Freud can be used to resolve past experiences in life.

References

Adler-Nevo, G., & Manassis, K. (2005). Psychosocial treatment of pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder: The neglected field of single-incident trauma. Depression and Anxiety, 22(4), 177-189.

Cartwright, R.D. (2006). Dreams and adaptation to divorce. In D. Barret (Ed.), Trauma and dreams (pp. 179-185). Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Eng, T.C., Kuiken, D., Lee, M.N., & Sharma, R. (2005). Navigating the complexities of two cultures: Bicultural competence, feeling expression, and feeling change in dreams. Journal of Cultural and Evolutionary Psychology, 3, 261-279.

Gaffney, D.A. (2006). The aftermath of disaster: Children in crisis. Journal of Clinical Psychology, 62(8), 1001-1016.

Kuiken, D., Lee, M.N., Eng, T.C., & Singh, T. (2006). The influence of impactful dreams on self-perceptual depth and spiritual transformation. Dreaming, 16(4), 258-279.

Punamaki, R., Jelal, K., Ismahil, K. H., & Nuutinen, J. (2005). Trauma, dreaming, and psychological distress among Kurdish children. Dreaming, 15(3), 178-194.

Revonsuo, A. (2000). The reinterpretation of dreams: An evolutionary hypothesis of function of dreaming. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 23(6), 877–901.

Valli, K., Revonsuo, A., Pa¨ lka¨ s, O., Ismahil, K. H., Ali, K.J., & Punama¨ ki, R-L. (2005). The Threat Simulation Theory of the evolutionary function of dreaming: Evidence from dreams of traumatized children. Consciousness and Cognition, 14(1), 188–218.

Valli, K., Revonsuo, A., Palkas, O., & Punamaki, R. (2006). The effect of trauma on dream content: A field study of Palestinian children. Dreaming, 16(2), 63-87.

Villalba, J.A., & Lewis, L.D. (2007). Children, adolescents, and isolated traumatic events: Counseling considerations for couple sand family counselors. The Family Journal, 15(1), 30-35.

Wade, C., & Tavris, C. (2008). Invitation to Psychology. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson.