Introduction

Art education is a significant factor in student development, improvement, and growth. Guns (2015) suggests considering art as a tool that can co-exist with human nature, supports its creativity, and cooperates with other disciplines in a way that promotes self-development. In the given paper, the chosen Key Learning Area (KLA), visual arts, will be discussed in the context of culturally responsive pedagogy.

Lewthwaite et al. (2015) state that by integrating cultural elements into the curriculum and considering the interests of indigenous students, educators may significantly improve teaching and learning outcomes. The paper will include a critical analysis of their study. Then, the review findings will be used to design a culturally responsive classroom activity.

Critical Analysis Reading

In this part of their article, Lewthwaite et al. (2015) discuss the inequity in school outcomes in the Australian education system. The researchers claim that there is a significant achievement gap between indigenous and non-indigenous Australian students, and the major factor contributing to it is teachers’ cultural unresponsiveness. Consideration of students’ backgrounds can significantly improve academic success. Thus, learning and instructional activities should be revised to make them more culturally relevant.

Article’s Description

By interviewing students, their parents, and teachers, Lewthwaite et al. (2015) aimed to identify what practices can potentially improve the academic outcomes for indigenous learners. They also attempted to determine which of teachers’ attitudes and behaviors may foster a favorable change. To support the research process, Lewthwaite et al. (2015) used the conceptual framework of culturally relevant pedagogy (CRP) that implies educators’ use of “the cultural knowledge, prior experiences, frames of reference, and performance styles of students to make learning more closely linked to and effective for them” (p. 134).

In the recent literature on the given topic, many other researchers also acknowledge the favorable effects of CRP on minority students’ performance in many disciplines including science and art. For instance, Aronson and Laughter (2015) state that it may foster better student engagement and motivation. Additionally, it is observed that by examining “their own beliefs, perceptions, and biases of education, their students, and other cultures,” educators may improve self-efficacy and quality of teaching (Gardner, 2015, p. 75).

Article Relevance

Nowadays, many Australian schools attempt to understand if it is necessary to use visual arts as an obligatory course in secondary education (Peake, 2016). Until now, traditional approaches to visual arts in schools and teachers’ ways of interacting with students were not very efficient (Lummis, Morris, & Lock, 2016). Thus, researchers find it necessary to discuss the role of arts in education, the possibility of education improvement through this discipline, or even a chance to prepare students to think critically, make decisions, and solve problems using their knowledge of arts (Torres de Eca, Milbrandt, Shin, & Hsieh, 2017).

At the same time, it is observed that multiethnic and multicultural art education can help students to think about distinct ideas represented in different art movements across the globe. As states by Gardner (2015), it can expose learners to the art of cultures they may not otherwise come in touch with and, therefore, multicultural art education is extremely important for public education as such.

The implementation of CRP in the chosen KLA is evident. By reducing the domination of the mainstream ideology in art lessons, making them more culturally diversified, and relevant to the ethnic class population, teachers may create more inclusive environments and develop greater awareness of cultural identities in students. It will help them to investigate the field of art and use all possible methods to improve their creativity in educational discourses.

Critical Summary

The issues related to the use of various pedagogy models bother many researchers, practitioners, and parents because not all of them assist in gaining benefits and realizing opportunities offered by Australian education programs (Polesel, Rice, & Dulfer, 2014). Lewthwaite et al. (2015) use various theoretical concepts, study methods, and research evidence to show that culturally relevant pedagogy can maximize potentials inherent with the Australian education system and support indigenous students’ academic achievements.

Background research

Through the review of the literature, Lewthwaite et al. (2015) identified the major dimensions of CRP and found out that teachers’ behaviors and perceptions largely affect students’ performance. In culturally diverse school environments, educators may sometimes struggle to meet the needs and interests of all students equally because they are unable to comprehend cultural differences and peculiarities. The scarcity of understanding of the cultural and linguistic diversity in teachers interferes with their professional performance and creates barriers to the academic and cognitive development of students.

The given ideas are consistent with the premises of Sociocultural theory introduced by Greenfield (2013) in her research paper. According to this theory, the individual’s process of education is not separable from his/her social and cultural contexts (Greenfield, 2013). Based on this perspective, teachers must raise awareness of the cultural differences and develop the educational strategies that would meet the interests and needs of diverse students. The consideration of the socio-cultural components of the cognitive processes is important in the creation of a positive school environment aimed to provide learning accessibility and ensure compliance with high standards of education proficiency.

Methods

Lewthwaite et al. (2015) employ qualitative research methodology. They conducted interviews with teachers, students, and their parents and analyzed their perceptions of current barriers to better education outcomes including educators’ cultural beliefs, opportunities for change in the education system, teacher-student communication, and so on. Qualitative data is interpretable and subjective. The methods used by the researchers provide information about the relationship patterns between the studied variables, e.g., students’ attitudes and the actual academic results; self-concepts, and barriers to knowledge (Keister & Grames, 2012).

Findings

The results obtained by Lewthwaite et al. (2015) reveal that teachers’ understanding of the cultural and historical backgrounds of indigenous students is essential. Parents expressed their hope for teachers to have positive perceptions of their children because when indigenous people are regarded as inferior, the quality of teacher-student and teacher-parent communication decreases. The development of positive dialogue in the classroom is considered by students as important as well. Additionally, they reported that the language teachers use may sometimes prevent them from better behavioral adjusting to the school environment and interferes with their understanding of educators’ demands.

Overall, the researchers show that teachers’ characteristics, values, and beliefs may significantly affect their attitude to students from distinct demographic backgrounds, their performance in class, and their abilities. The lack of understanding of how cultural and environmental factors influence children’s cognitive performance and a narrow view of how academic talents may be expressed in diverse students can lead to the formation of an inadequate attitude towards them.

Practice Recommendations

The findings allowed Lewthwaite et al. (2015) to develop specific practice guidelines. First of all, to redress cultural inequities in education, teachers should strive to establish trustful, respectful, and warm relations with students. They should value learners’ cultural identities by “showing respect for students’ home language and knowledge, family and community, values and beliefs” (Lewthwaite et al., 2015, p. 151).

Students’ learning activities should be scaffolded through appropriate strategies aimed to facilitate the switching from Aboriginal English and Standard Australian English. Additionally, teachers must be explicit regarding academic and behavioral expectations and should communicate them to children. Lastly, the shift from the teacher-centered model should be made towards the creation of a more student-centered form of learning.

Researching

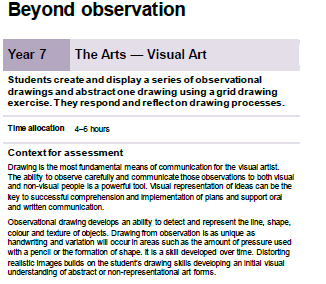

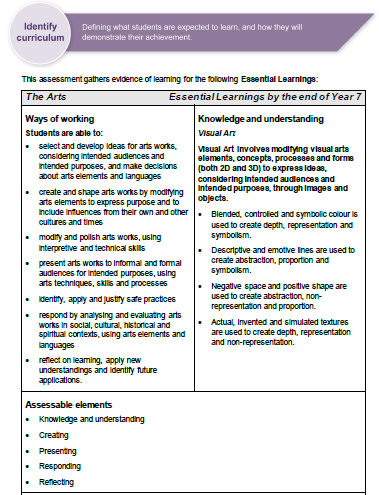

In this part of the work, the attention will be paid to one of the possible learning activities to be offered for students aged 9 years. A lesson plan titled “Beyond Observation” is chosen for the analysis (“Years 1-9 the arts: Visual art assessments”, 2017).

Observational drawing is the main learning activity that is developed on a foundation of background knowledge, a tutor’s role (that may be compared to the role of the Subject Superintendent), and critical “visual thinking” that is supported by new technologies and scientific management (Lummis et al., 2016). Tutors have to be models for students to explain what kind of work is expected, and the chosen activity is a good attempt to combine individual skills and knowledge with collective thinking abilities.

Learning Activity Introduction

According to Lewthwaite et al. (2015), visual imagery can be utilized to “prompt engagement and support learning,” and in a holistic approach to learning, new information and student’s skills can be “chunked and scaffolded, and connected to prior knowledge” (p. 152). Visual arts education and observational drawing, in particular, can be used as such a holistic educational method as it can easily be combined with the instructional activities from other disciplines such as history and cultural studies.

Tutors have to understand that arts education is not only a discipline where specific art concepts and terms are elaborated and used to create certain work. Arts pedagogy has to demonstrate specific abilities to go beyond arts learning and use the initiatives from different spheres (Anderson, 2016). It is possible to say that observational drawing is an activity with the help of which it is possible to develop numerous students’ skills, including critical thinking, observations, analysis, discussion, and comparison.

Assessment and Revision

According to Lummis et al. (2016), drawing is “central to any observation or design process” (p. 123). It is self-expression with the help of which students demonstrate their understanding of the work which may help educators to identify learners’ strengths and weaknesses.

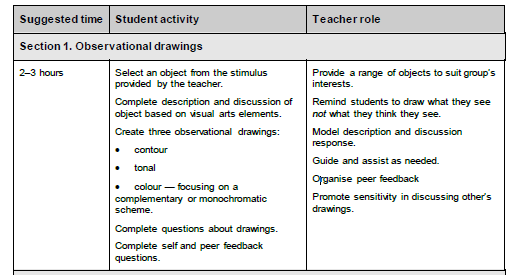

In the chosen activity, the major teachers’ tasks include the selection of an appropriate and culturally relevant object that will suit group interests, the guidance of students in how to start drawing and how to integrate the personal vision in what they see (“Years 1-9 the arts: Visual art assessments”, 2017). However, the role of students should not be minimized because they have to understand the level of their responsibility and the necessity to investigate their skills and abilities to make improvements.

Visual arts education may include numerous activities. Still, the drawing should be at the core because it may be interpreted as the “whole notion of investigation (Lummis et al., 2016). As a part of arts, the drawing should contribute to social attention, student engagement, and emotion regulation in people’s attempts to understand each other and depict their past in their present activities (Goldstein, Lerner, & Winner, 2017; Hursen & Islek, 2017).

Also, drawing lessons guide students in how they should develop their critical thinking and operate various communicable ways in their activities (Knight et al., 2016; Lazo & Smith, 2014). Some students may need additional help, and some students are eager to work independently to check what they can do and what aspects should be improved. Still, the most important thing they have to remember about visual arts is that different activities should be taken, and unexpected results may be achieved.

Taking into account the recommendations for practice suggested by Lewthwaite et al. (2015), as well as the visual arts framework in which it represents as a discipline contributing to the development of different skills in students, the chosen observation drawing activity provided by Queensland Curriculum & Assessment Authority can be revised and improved to achieve better academic outcomes for indigenous students and make sure that their involvement in the learning and instructional processes is equal to the teacher’s involvement.

First, it is necessary to admit that the activity begins with the necessity to select an object and discuss all possible visual arts elements that can be detected. However, such beginning proves that a learning activity is based on certain instructions, and no personal interests and demands are taken into consideration. Students get a task and complete it. Visual arts activities should be more interesting and promote students’ involvement. It is possible to begin this activity with a questionnaire or short interviews with students about their preferences in art or objects that they can like to analyze and evaluate. Students should share their background knowledge neglecting any frame and academic boundaries so that a tutor can identify students’ behaviors and moods.

Second, there are no specifications about what technologies and techniques are appropriate for the creation of observational drawings. Lummis et al. (2016) mentioned that several studio techniques available to students might build expressive and manipulative skills. If there is an opportunity to provide students with several options for observational drawings, this chance should be used.

Finally, the last tasks are based on the necessity to develop self and peer feedback on the work done. In this kind of work, students should be introduced to new instructions and expectations. The quality of instructions has to be enhanced through the introduction of policies and requirements (Lummis et al., 2016). It is also important to make sure that both students and teachers leave a classroom when they are done with the offered learning activity with high self-efficacy that is usually associated with “the mastery of skills and knowledge” (Lummis, Morris, & Paolino, 2014, p. 61). Satisfaction and knowledge in education play an important role.

Conclusion

In general, the evaluation of the lesson plan and the offered learning activity turns out to be a helpful method for implementing the recommendations given by Lewthwaite et al. (2015) and other researchers. Visual arts education is a complex discipline with an impressive history and significant contributions.

Teacher-student cooperation, critical thinking, stimulation, goal-solving activities, and decision-making processes can be improved in case a student understands what kind of work should be done in terms of the chosen course, and a tutor knows how to support culturally diverse students and arrange appropriate activities for indigenous students. Observational drawing, as a part of visual arts, promotes student development from different perspectives that cannot be neglected or misunderstood.

References

Anderson, M. (2016). Negotiating arts education research: Setting the scene. In J. Fleming, R. Gibson & M. Anderson (Eds.), How arts education makes a difference: Research examining successful classroom practice and pedagogy (pp. 29-38). New York, NY: Routledge.

Aronson, B., & Laughter, J. (2015). The theory and practice of culturally relevant education: A synthesis of research across content areas. Review of Educational Research, 86(1), 163-206.

Gardner, A. (2015). Critical analysis of culturally relevant pedagogy and its application to a sixth grade general music classroom. Web.

Goldstein, T.R., Lerner, M.D., & Winner, E. (2017). The arts as a venue for development science: Realising a latent opportunity. Child Development, 88(5), 1505-1512.

Greenfield, R. A. (2013). Perceptions of elementary teachers who educate linguistically diverse students. The Qualitative Report, 18(47), 1-26.

Guns, A. (2015). Examining secondary school students’ attitudes towards visual arts course. Journal of Computer and Education Research, 3(5), 166-182.

Hursen, C., & Islek, D. (2017). The effect of a school-based outdoor education program on visual arts teachers’ success and self-efficacy beliefs. South African Journal of Education, 37(3), 1-17.

Keister, D., & Grames, H. (2012). Multi-method needs assessment optimises learning. Clinical Teacher, 9(5), 295-298.

Knight, L., Zollo, L., McArdle, F., Cumming, T., Bone, J., Ridgway, A.,… Li, L. (2016). Drawing out critical thinking: Testing the methodological value of drawing collaboratively. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 24(2), 320-337.

Lazo, V. G., & Smith, J. (2014). Developing thinking skills through the visual: An a/r/tographical journey. International Journal of Education through Art, 10(1), 99-116.

Lewthwaite, B. E., Osborne, B., Lloyd, N., Boon, H., Llewellyn, L., Webber, T.,… Wills, J. (2015). Seeking a Pedagogy of Difference: What Aboriginal Students and Their Parents in North Queensland Say About Teaching and Their Learning. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 40(5), 132-159.

Lummis, G.W., Morris, J., & Lock, G. (2016). The Western Australian art and crafts superintendents advocacy for years k-12. History of Education Review, 45(1), 115-130.

Lummis, G.W., Morris, J., & Paolino, A. (2014). An investigation of Western Australian pre-service primary teachers’ experiences and self-efficacy in the arts. Australian Journal of Teacher Education, 39(5), 50-64.

Peake, R. (2016). Nation needs to consider high schools specialising in visual arts: Minister.The Canberra Times. Web.

Polesel, J., Rice, S., & Dulfer, N. (2014). The impact of high-stakes testing on curriculum and pedagogy: A teacher perspective from Australia. Journal of Education Policy, 29(5), 640-657.

Torres de Eca, T., Milbrandt, M.K., Shin, R., & Hsieh, K. (2017). Visual arts education and the challenges of the millennium goals. In G. Barton & M. Baguley (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of global arts education (pp. 91-106). London, UK: Springer Nature.

Years 1-9 the arts: Visual art assessments. (2017). Web.