Yayoi Kusama: Japanese Woman behind Dots

Nowadays, it became a commonplace practice among art critics to refer to the art of Yayoi Kusama as such that has a strongly defined ‘psychedelic’ quality to it. Kusama’s art is often regarded as reflective of the artist’s mental inadequacy with the famous ‘polka dot’ motif being considered essentially neurological. Such a point of view is, of course, is fully legitimate – especially given the unconventional aesthetic subtleties of Kusama’s artistic installations, the long history of psychosis, on the author’s part, and the fact that she never hesitated to admit of having been not altogether adequate, in the psychiatric sense of this word. As it appears now, the recurrent strikes of psychosis/depression served Kusama as the sources of artistic inspiration, “I often suffered episodes of severe neurosis. I would cover a canvas with nets, then continue painting them on the table, on the floor and finally on my own body”.

Nevertheless, the close discursive analysis of most Kusama’s works will reveal that being sublimation of the “oriental” workings of one’s psyche, her art pieces are not quite as eccentric and whacky as many people assume it to be the case. Even the most eccentric-looking of them are best discussed within the cause-effect (or rational) reasoning framework. In my paper, I will explore the validity of this suggestion at length while promoting the idea that Kusama’s art is consistent with the cognitive specifics of the “oriental” way of life, as a whole.

Yayoi Kusama has always been known as an utterly prolific artist who never experienced any emotional discomfort while experimenting with different artistic styles, as well as the actual mediums for conveying an aesthetic message. In this respect, we can mention that Kusama excelled in the domains of painting, street-performing, writing, etc. She also succeeded in establishing herself as a political activist, committed to the leftist liberal cause. Nevertheless, it was specifically Kusama’s artistic installations that brought her fame (although very late in her life) of the 20th century’s most controversial Japanese female artist.

Probably the most memorable of them was the room-sized installation Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field exhibited for the first time in New York in 1965. (Exhibit 1). The installation came in the form of “The mirrored room, specially constructed for the show… The four walls were lined with mirrored panels from top to bottom … The room was covered with a carpet of several hundred soft fabric protuberances that Kusama had made by stitching together sections of polka dot-printed cotton fabric”.

Once inside the room, visitors were exposed to the mirrored images of themselves with the dotted red and white pattern of the featured ‘phallic field’ serving as a background. It is now assumed that there were many feminist overtones to the artistic creation in question. As Muller noted, “Visitors can stand or lie or sit in the installation where the mirrors are set in such a way to endlessly reflect a self-reflected infinitely in the phallic field – a strong visual representation of the self’s deferral to phallocentric”. However, there appears to have been many more discursive dimensions to the Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field than merely the one concerned with sexuality. The main of them are inseparably interconnected with the already mentioned polka dot visual motif, which is now being regarded as Kusama’s artistic “trademark”.

The motif’s origins are usually discussed in conjunction with the fact that the author used to suffer from the neurological impairments (such as seeing “auras”) to her eye vision – something that is meant to justify the idea that Kusama is best referred to in terms of a “mad artist”. As Henderson and Pull argued, “Yayoi Kusama’s polka dot frenzy evokes powerful insight into the world of paranoid schizophrenia”. Nevertheless, it will prove rather inappropriate assuming that there is a necessarily pathological quality to Kusama’s art because of what was mentioned earlier. The reason for this is that despite the sheer eccentricity of many of Kusama’s art pieces, concerned with exploring the polka dot motif, the latter correlates well with the distinctively “oriental” characteristic of one’s psycho-cognitive reasoning – the person’s tendency to objectify himself/herself within the surrounding natural environment (as opposed to trying to control it, as it is the case with most Westerners). The validity of this suggestion can be illustrated regarding Kusama’s outlook on the significance of the polka-dotted patterns in her art, “Polka dots must always multiply to infinity.

Our earth is only one polka dot among millions of others… with polka dots, you become part of the unity of the universe”. The quoted suggestion leaves only a few doubts as to the context-orientedness of the very logic of the artist’s reasoning concerning what kind of message her art conveys. Consequently, this exposes Kusama as someone who never ceased being “ethnically minded” – the idea that stands in contrast to Kusama’s reputation of an intellectually liberated cosmopolitan. After all, one’s tendency to indulge in the contextual type of thinking has always been considered “innately oriental”, “In a variety of reasoning tasks, East Asians take a holistic approach. They make little use of categories and formal logic and instead focus on relations among objects and the context in which they interact”.

What this means is that having been quintessentially “ethnic”, Kusama’s art cannot be regarded deviant – at least in the sociological sense of this word. In its turn, this partially explains the strongly defined ethnocultural overtones to how the artist used to go about accentuating its “otherness”, “Kusama intentionally emphasized the ‘otherness’ of her identity as a Japanese woman by wearing her quintessential gold kimono… She took advantage of being seen as an outsider to attract attention”. There is another notable quality to a person’s predisposition towards the context-oriented (holistic) type of cognitive thinking. Its practitioner is naturally driven to assess the surrounding reality’s emanations in conjunction with what accounts for the varying measure of their utilitarian usefulness – another indication of one’s endowment with the “oriental” mindset.

The above-stated provides us with the important clue, as to what should be deemed the discursive implications of yet another “trademark” feature of Kusama’s art – the fact that it used to violate the provisions of socially constructed morality in the West, which resulted in Kusama having been arrested on several different occasions through the sixties and seventies. In this regard, we can mention Kusama’s famous “happenings” (now referred to as performance art), which were, in fact, the exhibitions of male and female nudity in public – deliberately designed to result in triggering as much public outcry, as possible. For example, as a part of Kusama’s 1968 Naked Protest at Wall Street “happening” (held in New York), “Four naked participants danced to the sound of bongo drums while Kusama sprayed them with polka dots (the police quickly closed the event down)”. Kusama’s Homosexual Happening, held in the same year, proved even more shocking (Exhibit 2). The artist’s formal stance on the semiotic meaning of phallic/nudity motifs in her performance art was concerned with Kusama continuing to stress out the importance of “sexual liberation”, “Kusama was especially keen on projecting an image of herself as a sexual liberator.

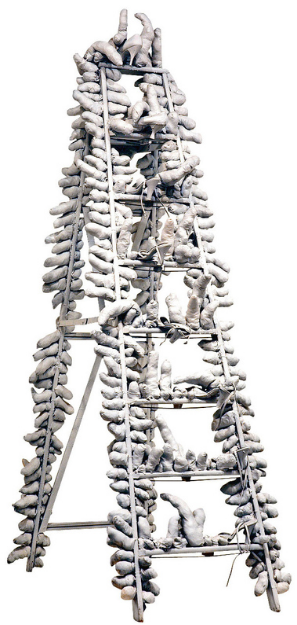

At the time of Homosexual Wedding in November 1968, Kusama served as ‘The High Priestess of the Polka Dots’”. Therefore, it does make a certain sense for art critics to be trying to recognize the presence of some hidden feminist themes in just about every of Kusama’s artistic works, such as her 1964 sculpture Travelling Life (Exhibit 3). While interpreting the semiotics of this particular artistic exhibit, Yoshimoto stated, “Women are represented by high-heeled shoes, attempting to climb up the ladder, whose steps are filled with white phallic forms of different sizes… this work symbolizes ‘womanhood menaced by men’”.

Nevertheless, unlike what it used to be the case with Kusama’s elaborations on the significance of the polka dot motif, the artist’s explanations of the essence of her obsession with “phallocentrism” never sounded convincingly enough – at least when assessed from the psychological perspective. As Kusama once pointed out, “I make a pile of soft sculpture penises and lie down among them. That turns the frightening thing into something funny, something amusing”. And yet, as psychiatrists are well aware of, those psychotic patients who experience the unconscious fear of phallic shapes could not care less about the actual material out of which these ‘freighting shapes’ are made. Therefore, Kusama’s statement appears misleading. The artist’s mental fixation on penises had very little to do with her presumed commitment to the cause of liberating women from patriarchal oppression.

Rather, this fixation was reflective of the sheer strength of the dominance-seeking instinct in Kusama. After all, there are plenty of indirect indications that while striving to position herself as the ardent critic of Western consumerism and benevolent prophet of “sexual liberation”, Kusama never ceased trying to gain the reputation of a famous artist while expecting that this would enable her to become rich – pure and simple. Having been a holistically-minded person, Kusama proceeded taking care of such her existential agenda in the most energetically efficient manner – by making her artistic escapades as scandalous, as possible. This is the actual reason why most of Kusama’s artistic statements balanced on the edge of ethical appropriateness. What this means is that, contrary to the opinion of many “progressive” critics, there are no hidden messages to be found in Kusama’s performance art.

By exposing audiences to her phallocentric installations, Kusama was trying to provoke the former to react emotionally to what they saw while anticipating that this would attract the media’s attention. Then, it would be only a matter of time before she could turn her “artistic wackiness” into a money-generating asset. Kusama, however, did not take into consideration the fact that at the time there were thousands of other mentally deranged and fame-seeking artists (affiliated with the Fluxus movement) in New York, who directly competed with her for the place under the Sun while relying on the “cost-effective” (scandalous) strategies of winning people’s attention. This explains the comparative recentness of Kusama’s popularity as an artist – despite the person’s advanced age.

I believe that the deployed line of argumentation, in defense of the idea that Kusama’s art is not quite as phenomenological as many contemporary art critics tend to think of it, is fully consistent with the paper’s initial thesis. To be able to grasp the actual significance of this person’s art, one merely needs to possess a basic understanding of what the notion of “oriental” mentality stands for, as well as to be aware of the essentially animalistic (concerned with dominance-seeking) nature of a person’s commitment towards achieving self-actualization through art – especially if the affiliated individual does not appear to have much artistic talent. Thus, it will only be logical to conclude this paper by suggesting that there is indeed much rationale to the practice of subjecting art to the reductionist analytical inquiry – even though most artists would find this practice utterly inappropriate and even offensive.

Bibliography

Applin, Jo.Yayoi Kusama: Infinity Mirror Room – Phalli’s Field. Springfield: MIT Press, 2012.

Bower, Bruce. “Cultures of Reason.” Science News 157, no. 4 (2007): 56-60.

Henderson, Daniel and Emily Pull. “Exhibition: Walking in My Mind.” Student BMJ 17, no. 5 (2009): 1-6.

Kusama, Yayoi. Infinity Net: The Autobiography of Yayoi Kusama. London: Tate Publishing, 2011.

Muller, Vivienne. “The Dystopian Mirror and the Female Body.” Social Alternatives 28, no. 3 (2009): 29-34.

Reisel, Mary. “PostGender: Gender, Sexuality and Performativity in Japanese Culture.” Asian Studies Review 36, no. 2 (2012): 284-286.

Sliwinska, Basia. “Yayoi Kasuma: Social Transformation through Infinite Multiplication.” Sculpture 31, no. 7 (2012): 36-41.

Yoshimoto, Midori. Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York. New York: Rutgers University Press, 2005.

Exhibits