Introduction

Agriculture is supposed to be the most powerful sector in a growing economy. If we dismantle all merchandise trade barriers and farm subsidies, surely it will show benefits in the whole development of the economy. The developing countries therefore should rightly focus on the agriculture sector and negotiations.

It is seen that there are disparities between the agricultural policies of rich countries and their consequent impact on poorer ones lies in the fact that the current distribution of over 90 Billion Euros in farming subsidies has widened the gulf between the rich and poor countries. It is seen that through farming subsidies the rich countries like USA, Germany, UK, France, Netherlands have a larger segments of subsidies than the poorer countries like Spain, Italy, etc. This is because agricultural policies are leaning heavily in favour of prosperous and urbanised countries rather than countries based on fingers and peripherals areas. (New research backs reform of EU farming subsidies. 2008).

Almost all the developing countries including the G-20 – are emphasizing on needs for cuts in subsidies. (Agricultural Market Access: The Key to Doha Success. 2005, p.1).

Aspects of Common Agricultural Policy

Even the reforms initiated in the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) fails to provide the necessary impetus to the economic considerations of developing countries.

The main factors lie in the fact that the US gives loans to poorer countries, but as part of the bargain, the countries are forced to import wheat, etc, from the USA, even though they may not be wheat-consuming countries. It is seen that the agricultural policies pursued by the USA is in terms of offering food aid to poorer countries to buy food. The export of foods is beneficial to the exporters but it does serious harm to the importer, since the local producer is put at heavy losses without market outlets to sell his produce. Most local governments fail to realise the fact that the multiplier effect could convert much of the money spent on inputs to be multiplied several times. Taking the case of Thailand, for instance it is seen that 43% of the Thai population fall in the poorer category, “even though agricultural exports grew an astounding 65 percent between 1985 and 1995.” (Shah 2005).

Again, taking the case of Kenya, it is seen that it was a self sufficient country but in 1992, EU sold produce to Kenya at 39% cheaper rates than the prices paid by EU to the European farmers, and finally the Kenyan market failed due to oversupply. (Shah 2005).

Stance of the World Trade Organisation

It is further seen that the less developed or developing countries have placed resistance to the global pressures to reduce trade barriers regarding the World Trade Organisations. (WTO). This is specially so in the case of the agricultural produces. It is seen that in the case of many of the countries severe declines have set in, because the local producers are not able to compete with the US imports, and also imports made by developed countries like Japan, Europe, etc., since in all these countries there are heavy subsidies, which significantly lower costs which Third World producers cannot match. Therefore, at the World Trade summit held in 2003 in Mexico, attempts were made to solve this vexatious issue, but it could not be amicably resolved.

However, during 2004 at the summit talks held in Geneva, Switzerland, “147 members will cut rich countries’ farm subsidies in return for developing countries opening markets for manufactured goods. The implementation of the agreement presents obvious internal political challenges in the developed countries.(Globalization, free trade, foreign trade. 2006).

Food and Agricultural Organisation (FAO)

In this context, it would be necessary to quote remarks of the Asst. Director General of Economics and Social Department, FAO, Mr. Hartwig De Haen who has said that the long term fall in prices of agricultural commodities along with significant increases in exports has polarised the developing countries into two parts. On the one hand, these countries are not less dependant on just a handful of commodities having high value exports, and some have shifted into production of high value export items; on the other hand, we also have the least developed countries who have not been able to make new investments in high value export agricultural crops, and they also have problems in meeting high exacting standards of global supermarkets.

The report warns that “these problems are exacerbated by market distortions, arising from tariffs and subsidies in developed countries, tariffs in developing countries and the market power in some commodity supply chains of large transactional corporations.” (Riddle 2005).

The aspects of oversupply and high tariffs of products

It is seen that there are a host of factors that contribute towards the impact of growing economies due to the actions of developed economies. For one thing, the aspect of oversupply is significant because it would tend to undermine the economy of developing economies substantially. Therefore it is necessary that necessary steps are taken to counter this aspect, through advertising etc. Further it is seen that high tariffs also act as an impediment for developing countries since the high tariffs paid for imports may not be able to be recoverable from exports, and thus the developing economy is put under substantial amount of pressure situations.

Maladies of developing economies in terms of limited product choices

Another factor regarding developing economies is that in some cases, they are dependent upon just a few commodities for revenue generation. It may even be the case that a country may be dependent on just one commodity for revenue generation. This characteristic is typically found among sub Saharan and other African economies. Should the prices of these commodities fall in the international markets; its impact would be felt in the domestic markets also. “Tariffs, subsidies and other trade-distorting policies in developed countries have to a large extent eroded the market share and revenues of exports by developing countries.

But policies, priorities and conditions within the developing countries themselves have also contributed to their loss of competitiveness and inability to diversify into more profitable and less volatile sectors.” (The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets. 2004, p. 24).

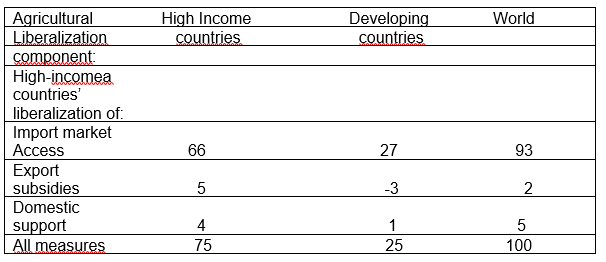

It has been documented in this context that 93% of the welfare gains from removing the distortions in the agricultural investments on a global level could be achieved by removing of the import tariffs, since this has proved to be the major issue impinging the differences between the economies of richer and poor nations. It is also seen than only 2% pertains to export subsidies and 5% to the domestic supply markets. (Agricultural Market Access. 2005).

Differences between economy perspectives of developed and developing economies

It is further seen that the perspectives of the developed countries and the developing countries towards agricultural policies and their implementation are quite different. It is seen that in the case of most of the developed countries, the contribution of agriculture to the national income, employment or GDP is not as significant as it is to the developing countries like China, India, Brazil, etc. This is because in these countries agriculture forms the nuclease of the livelihood of families and invariably, only source of incomes.

Thus it is not surprising that the attitudes of the developed countries would be quite different from that of developing countries, where it is necessary to stabilise prices of agricultural commodities and also ensure abundant availability in order than people do not remain hungry or starved. But this is not so in the case of developed countries since their fooding and other basic needs are well taken care of. Further major foreign exchange earnings come from exports of agricultural produce in the case of developing countries which may not be the case of developed countries where industry and commerce play crucial roles in foreign exchange earnings. (Stockbridge 2006).

It needs to be emphasised in this context that the scenario facing developing countries today is different from what was available around 3 to 4 decades ago, in that sea changes have occurred in terms of economic fundamentals and how they impact upon the growing economies of these countries. With globalisation and open markets, the need for developing countries to remain globally competitive and fighting fit is necessary if it has to raise the economic standards of its country.

It is also necessary that growing economies realise that although agriculture is the bulwark of their economy, it also needs to make paradigm shifts in order to create a stronger economic agricultural base for future years. For developing and underdeveloped countries, the available for food for population is uppermost in the agricultural agenda, and this could be done by producing abundantly, and thus making agricultural produce cheaper and available to everybody.

Price stability and controls in agriculture, which is vital for sustenance and growth of the economy also should percolate to the lower echelons of the society and the benefits of lowered prices due to economies of large scale production should be passed on to the rural population also.

Subsidies and Trade Barriers

While considering agricultural policies pursued by developed and also developing countries, different aspects need to be taken into account, like marketing, input-output policies, credit, mechanisation, land reform, irrigation technologies, methods of research, as also study status of the role of women in formulation and execution of agricultural policies.

Subsidies and trade barriers should be effectively sorted out by the Government for social and environmental benefits, as also the costs of reducing subsidies and trade barriers. (Anderson 2004).

If wasteful subsidies offered and spent by the Government and trade barriers are used in better ways, the amount can be utilised to actually achieve the objective of the subsidy, or be saved to be spent at the next best opportunity. The trade reform policy will allow people to spend more effectively on other issues under free trade, thus resources could be allocated more efficiently. This will also indirectly contribute to newer opportunities and bring out new challenges.

To understand the undesirable effects of subsidies, it would help to take a look at the case of European Union and its Common Agreement Policy, and the way that, although it initially satisfied all parties, eventually it turned as a huge detriment not only for their own people, but also members of the Third World markets in particular, and also world trade at large. By dumping their surplus produces onto Third World countries, they damage the general equilibrium of trade and create conditions which encourage price wars on an international level which could be exploited by unscrupulous global traders.

“If a company exports a product at a price lower than the price it normally charges on its own home markets, it is said to be ‘dumping’ the product.” (Understanding the WTO. 2008). If we were to consider the studies relating to the role of the European Union (EU) in promoting unfair subsidies that adversely affect the economics in developing countries, the following factors are found:

How CAP activities vitiates agricultural exports

The Common Agricultural Policy (CAP), an agreement signed among EU Countries allows subsidies to the large-scale farmers and agricultural industry owners to such unethical levels that the agricultural exports of EU are unfairly lower priced, for the rest of the world to match. It not only affects export markets of developing countries, because they will not be able to export at such low costs, without the benefits of any concurring subsidies, not only because domestic markets in the developing countries would be harmed, but because the imports from EU will be cheaper than their outputs.

Unless CAP is appropriately amended, the farmers in the developing countries will find it difficult to hold on to their only source of livelihood. This is because they cannot sell their produce in their own country and they cannot export it to other countries at competitively unfair prices. This is caused primarily by the fact that EU gives enormous subsidies for its export produce which causes detriment to exports of other countries since they cannot match low prices offered by EU Countries.

The Mozambique and Jamaica issue

Research has shown particular instances where EU exports have destroyed the markets of developing countries. The sugar markets in a poor country like Mozambique are a pertinent case. The dairy products market in Jamaica and India is other relevant case.

It is important to note here that Mozambique, India and Jamaica are instances of some of the most developing countries in the world who depend largely on agriculture produce to provide gainful jobs for their rural population.

It is now necessary to take up the case of EU’s Sugar exports to Mozambique, who happens to be one of the poorest nations in the world, with around 80% of its people living solely on agriculture in rural areas. Owing to a lot of activities done by the UNO and other agencies, Mozambique has a reasonably good output of sugar and their cost of production is much lower to that of EU countries. This should give Mozambique a gainful opportunity to export sugar to other Third World Countries, or at least to neighbouring countries like Nigeria and Algeria. But this is not the true picture. EU has been exporting Sugar to the African countries at rates that Mozambique just cannot match because EU exports are heavily subsidised.

It has been the practice of the European Union countries to dump their surplus produce of sugar, thereby, destroying the livelihood of small time farmers in Mozambique. “Because Europe dumps its excess production overseas, it pushes other exporters out of third markets. In 2001 Europe exported 770,000 tones of white sugar to Algeria and 150,000 to Nigeria – these are lost export opportunities for more efficient producers in southern Africa.” (Sweet sufferings).

Again, taking the case of Dairy products markets in Jamaica and India. Dairy dumping has hit marginal farmers in these countries. India, for instance, largely through the efforts of a large scale campaign called Operation Flood, funded jointly by EU countries, UN Food Programme, World Bank, to the tune of billions of dollars, has become the world’s largest producer of Dairy products in recent years. Riding high on its huge domestic market the farmers have enjoyed reasonable returns for their efforts but with the advent of CAP, the EU has abruptly stopped India’s progress. India’s efforts to export its dairy products to the Gulf countries, South-East Asian countries, etc., has not met with much success, since relevant studies have found that there are no buyers for Indian dairy products since the dairy exports from the EU are priced cheaper, although their cost of production is much higher than that in the Indian context..

In Jamaica, even the local dairy processing units find themselves in a situation of having to use imported EU milk because it works out to be much cheaper than the produce of local farmers. This is an unenviable situation which could hamper whatever little economic progress developing countries are making on their road to improving the quality of life for their people.

The under mentioned table depicts the statistics on poverty and human welfare for 10 developing countries and three developed countries.

**Less than 1%: (Economic Conditions in Developing Countries. 2008).

From the above table it is seen that the maximum percentage of people living below the poverty line are in Nigeria, followed by developing and underdeveloped economies like that of India, Bangladesh and the Philippines. The most underdeveloped people are found in Bangladesh according to this statistical table of 2002-04. Again the highest infant mortality rates are also found in Nigeria and the lowest in Japan. Life expectancy for Nigerians is the lowest and for the Japanese it is the highest. It is seen that Brazil and China could be considered as developing economies.

How farming community in EU are deprived of benefits

Ideally, millions of agricultural producers across the world should have equal opportunities to trade their produce in local, regional, national and international markets. Yet, many small farmers in developing countries face acute market conditions, lost market shares, lowered margins of profits and unfair competition due to their inability to face up to undercutting and unfair competition from unscrupulous trade cartels.

Through CAP agreement, EU is subsidising the price of their agricultural products to as low as 34% of their production costs. However, this gives a false impression that farming community in European countries are financially well off. The ground realities are that the common farming community in EU countries are not benefited by CAP. On the contrary, the only beneficiaries are large agricultural and industries houses who, thanks to their lobbying capabilities, emerge as their main gainers.

Countries like France and Spain have sponsored largesse of subsidies for their industrial farmers from the EU. By making the rich farming industrialists even wealthier through lopsided subsidies, the EU has only been able to hasten marginalisation of small holdings farmers in their own territories.

CAP was developed in the early 1960s as a mechanism to support and develop farming in Europe and through which a stable internal food supply and a high level of self-sufficiency could be made possible. Two decades later, over supply in the European market made international marketing inevitable, and through Amendments in CAP enforced since 1992, EU pursued active campaigns to make its exports over competitive, through subsidies and unfair pricing.

The CAP has by far outlived its utility and need to be radically reformed. Any subsidies that promotes over production and exports into international markets at prices lower than its production cost should be banned. Anti-dumping laws should be formed to regularise exports made at unfair prices.

Dumping and its evils

EU should act responsibly and responsively to the needs of Third World countries. Dumping damages their economy, the livelihood of their poor farmers and questions the rationale of UNO and other world agencies who work to upgrade the quality of life of developing countries. (Godfrey 2002).

The dumping measures are taken by the developed countries in order to protect themselves from the gains derived by developing countries with nascent industries, even though such dumping is illegal under US anti-dumping legislation. Nevertheless, the WTO members are more commonly using the anti-dumping measures. Canada happened to be one of the pioneer countries who decided to impose anti dumping measures in order to protect its economy from competition of developing countries

The trade reforms will also reduce poverty, which, ultimately will lessen degradation of environment, and take over other challenges like change in climate, conflicts, communicable diseases, educational investment, stable finance, corruption, population, water issues, hunger and malnutrition etc.

“Not all subsidies are welfare-reducing, and in some cases a subsidy-cum-tax will be optimal to overcome a gap between private and social costs that cannot be bridged a la Coase (1960). Throughout this paper all references to ‘cutting subsidies’ refer to bringing them back to their optimal level (which will be zero in all but those exceptional cases).” (Anderson 2004).

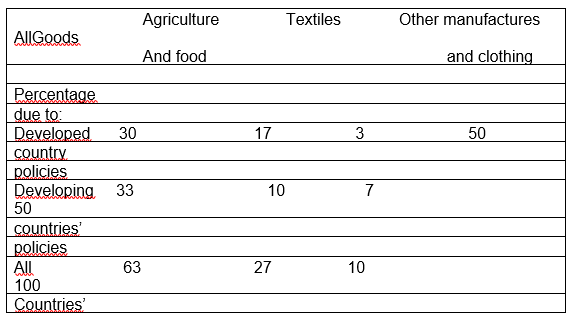

However, regardless overall benefits of reducing most of the Government subsidies, and apart from the open trade, most of the national government interference in the market for goods and services which can harm the International commerce. Such Governmental interference inversely effects the most to worlds poorest community mainly agriculture and clothing. Action should be taken to get rid of such policies which harm economic developments, and the Government’s international trade negotiations should have some influence both at home & abroad which excludes basic taxes on income, consumption and value added, government spending on mainstream public services, infrastructure and generic social safety nets.

Generally Agreements on trade and tariffs

In making up the 1995 GATT, World Trade Organization oversaw the fact that the tariffs on imports of manufactured goods were lower in most of the developing countries and the manufacturing tariffs remained high, but unfortunately the distortion of subsidies and trade policies were continuously damaging effectiveness of resource allocation, growth of economy and reducing poverty.

In the year 1994 agreements were made under multilateral trade registration, which came into effect by year ending 2004, under which many trade liberalization policies were there, many of subsidies and trade distortion will remain which includes not only trade taxes, but also protection against the anti-dumping, some remedies against technical barriers against trade and domestic production subsidies. Insufficient or excessive taxation and lack of measures to reduce pollution can also lead to inefficiency and effect trade adversely. Under certain conditions the arrangements are leading to trade and investment distraction rather than creation.

How economic distortions could be ironed out

The chances of lessening trade distortion is very low, as policies relating to this can effect government treasure, as most of the countries government heavily depends on the trade taxes for revenue. The distortion remains mainly because if the Government reforms or become less strict towards trade and cuts of subsidies, redistribution of jobs, income and wealth can reduce the governmental power.

The government should find out new effective ways to sort out current distortions in world market by bringing out new methods on market for goods, capital, services including labour, which should focus on trade taxes, subsidies, restrictions on quantity, and technical barriers, as also some of the trade distorting production subsidies.

Studies show that there can be gains as well as losses by removing subsidies and trade barriers.

Many times the gains from trade can be higher as share of national output with countries of smaller economy, mainly in economies where production has not been fully exploited and variety of products is preferred by consumers. In such cases the firms which are more competent with mounting industries can take over the less efficient ones. It is seen that if resources are used within the industries rather than in between the industries the chances of welfare increases.

Increase in trade barriers can allow ‘imperfect competition’ in the domestic market, which is more commonly found in smaller economies where number of firms is less in the industry.

How trade barriers could affect economic growth

In a helpful survey done in year 1999 by Taylor, several points have remarkably shown the economic growth through open trade system. Even as per the survey by USITC-1007, there are ample evidences which strongly supports that open economies have faster growth and progress.

Studies have also shown that freeing up of the importations of capital and intermediary goods; can promote investments which can lead to increase economic growth. The developing economy can grow faster by import of capital goods rather than domestically producing them.

Eastery (2001) studies that people respond to investments, like investment in education, health, agricultural researches etc. Getting incentive right in factor and product market is part of that process.

Nevertheless, the developing economy to attain higher growth rates the Government should have good institutions which can allocate and protect property rights, allow the domestic and product market to operate freely and ensure stability of political and macroeconomic conditions. However, the only fact of trade openness cannot bring all round economic growth in all sectors because other factors such as even and proper investment, implementation, education of the participants etc. should be taken care of.

Despite all the facts that removal of trade barriers can improve the economy of the nation, in most of the countries the government still continues to be protective towards foreign competition for at least some of their industries. There can be various reasons for such trade barriers by the Government, like assisting the upcoming or new industries, unemployment, payment maintenance, revenues and taxes etc. should be taken care of.

It is also seen that changes in price of products resulted from open trade or no subsidies can change the value of service of production such as land, labour and capital. Therefore even though the aggregate of nation wealth may increase, individual rise is not likely expected and gain per consumer can be low.

The benefits of reduced government involvement in markets, is accepted by majority as also the profits of lower subsidies and trade barriers. Magazines like The Economist and other daily publications are bringing out awareness in respect of the virtues of open market.

The studies relating to the reduced subsidies and trade barriers have very much been able to persuade all Governments to fully free up their trade and the profits or gains derived from such opportunities would be measured by gains from moving the current world to one free of subsidies and trade barriers.

America is making efforts of on making a Free Trade Area, potentially bringing together economies of north, central and South America. The FTA negotiations by US & EU are together with variety of other countries, and are more advanced than other proposed FTAs like in south Asia and China & south East Asia.

- Cotton trade and production are highly distorted by policy. More than one-fifth of world

- Cotton producer earnings during 2001/02 came from government support to the sector.

- Support to cotton producers has been greatest in the US, followed by China and the EU.

For 2001/02, US combined support to the cotton sector was US$2.3 billion. The EU’s support (to Greece and Spain) totalled US$700 million. Subsidies encourage surplus cotton production, which is then sold on the world market at subsidized prices. This has depressed world cotton prices, damaging those developing countries which rely on exports of cotton for a substantial component of their foreign exchange earnings.

A number of West and Central African countries raised the issue of the abolition of cotton subsidies at the WTO in May 2003. Cotton subsidies also form the basis of a WTO dispute brought by Brazil against the US on 26 April 2004 in which the panel ruled in favour of Brazil. The expansion of cotton cultivation in many developing countries has played an important role in reducing poverty, where scope for replacing cotton by other crops is limited.

These gains have been threatened by the fall in world prices for cotton. Cotton is a minor component of economic activity in industrialized countries, accounting for only 0.12% of total merchandise trade, but its production plays a major role in some Least Developed countries in West and Central Africa. In Benin, Burkina Faso, Chad, Mali and Togo cotton accounts for 5-10% of GDP, more than one-third of total export receipts and over two-thirds of the value of agricultural exports. Even in Côte d’Ivoire and Cameroon (both classified as developing, not Least Developed), which are among the largest African cotton producers, cotton production accounts for 1.7% and 1.3% of GDP.

Cotton is also a major component of total exports for a number of non-African developing countries. Cotton exports in Uzbekistan, Tajikistan and Turkmenistan account for 45%, 20% and 15% of total merchandise exports and make a significant contribution to GDP in these countries (8% in Uzbekistan and Tajikistan; 4% in Turkmenistan).

From this particular instance regarding the cotton trade itself; it is easy to understand the perils of subsidies in developed regions like US and EU and how it adversely affects the opportunities for the farmers in developing countries in Africa and Asia. Considering the fact that how important Cotton is to the economies of small developing countries with no other major crops to speak of, the subsidies given in the developed countries are totally unfair and they need to reform their policies as a responsible country towards the poor countries. (Gillson et al 2004).

Report of World Bank on Agriculture

The World Bank from past 25 years, for the first time in its annual report focused on development of agriculture and small farmers and reduction of poverty. The report shows that if the wealthy nations like United States and Europe removes the subsidies an other tariffs on agricultural products like cotton, soybeans, other oil seeds, the developing nations share in world trade of such agricultural products can raise to 80% by the year 2015.In the year 2007, studies reported that the food production all over the world was enough to double the population, yet millions of people went without food, only because of unwanted amount spend on agricultural subsidies by developed countries.

If the richer countries get rid of subsidies, they can save lots of funds and become healthier. The developing countries will get fair chances in trade.

Most of the economic research show that subsidies are hopelessly inefficient in view of agricultural development in developing countries.

The policies by congress to save small farmers are rather proved to be reason for their demise. Here the owners of bigger farms receive large share of government subsidies by which they can buy more property like land etc., which can adversely affect small & upcoming farms.

In the year 2006, incident regarding a group of farmers were brought into notice were they received no subsidies so far, mainly the garlic producers, who faced the problem of under cutting by China importing the product at half the original price.

In a report made by Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz, over 60% of US farmers don’t get any subsidies at all yet manage to survive. Even in case of New Zealand, after abandoning subsidies unilaterally, some years ago, its farming industries survived without any serious reverses.

The OECD report on agriculture subsidies says that by cutting tariffs and export subsidies 80% benefits can be seen in agriculture for the most efficient agriculture exporter, however, the developing economies benefits would be relatively less as they will be more concerned in manufacturing fields rather than agricultural trade.

It should be agreed that if the foreign oil imports are reduced by the United States, the developing countries will get a big economic lift, as they will be able to grow traditional crops more efficiently without bothering to compete against US subsidies.

Pietra Rimoli discovers that, removal or abolition of subsidies only cannot help poor countries; there are lots of other trade barriers which come across these developing countries which also should be taken care of. (The gravy train rolls on. 2005).

Under the world development report-2008 on agriculture for Development, development of agriculture plays an important role in achieving millennium development goals and reduction of extreme poverty and hunger. The report also guides the Government of international community for improving agriculture, which can change lives of millions of poor people in rural areas. In many of the poor countries development of agriculture can be one of the important factors for overcoming poverty and enhance food security.

Taking into consideration the rapidly growing domestic and international markets, as well as the new technical and institutional innovations in markets, revolution in biotechnology and information technology, provides more opportunities for agriculture to promote development. The renovation of agriculture today gives opportunity to hundreds and millions of poor public under rural region to move out of poverty with right policies and supportive investments at local, national and international level.

How development activities in agriculture could be carried on

However, agriculture alone is not enough to materially reduce poverty, even though it is a powerful source. Lots of improvement has to be done, like in the transforming countries, which include most of south & east America and Middle East and north of Africa, rapidly rising rural urban income disproportion and continuing extreme rural poverty are major tensions for political and social organization.

The improvement in civil society empowerment, particularly of producer organizations is essential as well as power at all levels. Improved Agriculture can be one of the top reasons for reducing poverty and improving development, but the benefits will be found only if Government and other donors change their pattern of underinvestment and disinvestment in agriculture. Top priority should be given to increase assets of poor, and make small holders, as also make agriculture more productive and create more opportunities in rural areas.

Under agriculture more sustainable production systems should be found out, for which the property rights should be strengthened and get right incentives as also remove subsidies that encourage degradation of natural resources.

The World Bank report mentions that, “Agriculture can contribute to development as an economic activity, as a livelihood, and as a provider of environmental services, making the sector a unique instrument for development”.

Other barriers for development of agriculture includes rapid population growth, declining farm size, soil infertility, missed opportunities for income diversification and migration.

The excessive tax policies and underinvestment in agriculture are to be blamed very much in bringing down the agriculture development; such policies are most found in economies giving priority to urban growth.

The world market prices of traditional products like cotton and coffee, questions the survival of millions of local producers. Reduced taxation and more liberalization of export markets have improved income levels in many countries. Nevertheless Government has to take care of regulating fair and efficient trade operations in the market.

It has been noticed in places like Sub Saharan Africa, products like seed and fertilizers, market failures still continue because of high transaction costs, risks of economies scale etc. Here low fertilizer use is one of the major barriers in growth of agriculture.

Like any of the subsidies, the input subsidies also should be used with extra care, as they have high opportunity costs for the productive public goods and social expenditure. Although proper use of subsidies can reduce risks of early adoption of new technologies and achieving economies of scale in markets to reduce output prices.

Subsidies need to be part of a comprehensive strategy to improve productivity and must have credible exit options.

Rapidly growing private investment in research and development, the knowledge divide between the developed and developing countries is huge. Including both private and public sectors, developed countries only invest ninth part of what Industrial or developed countries put into Research & Development under Agriculture, as share of Agriculture GDP. Revolutionary progress in field of biotechnology also can bring large benefits to the poor or new producers and consumers.

Development of agriculture is not an easy task though; it needs proper implementation agenda in terms of increasing efficiency of small holders and private organization and state. Institutions helping development of agriculture and providing knowledge or innovating new technologies helping progressive agriculture as also proper use of natural resources and mobilizing political support, skills and resources etc.

Today the awareness of benefits of development of agriculture has improved opportunities and more people are ready to invest in agriculture, which shows that agendas for agriculture development can go ahead with proper implementation and guidance. (World development report-2008: Agriculture for Development. 2007).

“Governments in rich countries are paying over $300 billion each year to subsidise their agricultural sectors – six times the total amount of aid to developing countries. That is enough to feed, clothe, educate and provide healthcare for every child on the planet.” (Farmgate: The developmental impact of agricultural subsidies).

WTO Developments

Further it is seen that under the World Trade Organisation (WTO) directives, which are imposed on the other WTO member countries, it is felt that subsidies that impinge on trade need to be removed. This has been duly carried out and since the year 1996, both the USA and the EU have reframed their subsidy schemes in order to move payments to farmers directly rather than offer price support, in order to obviate the subsidy reduction.

Since the developed countries have the required infra-structure, this is possible, but this may not be allowable, in the case of developing countries who may not have the level of literacy or build-in infrastructure that could take up this enormous tasks. Therefore, in numerous ways, the developing countries stand to lose since they are not in a position to compete with the developed countries in the matter of affording subsidies to farmers on a very large scale.

Thus it is seen that the EU and the US farmers are receiving subsidies, which may be a risk factor for the farmers in developing countries since these disparities would eventually reflect in the sale prices of agricultural produce for the seller and the buyer.

As has been mentioned, the subsidies have the effect of making local farmers pricing uncompetitive and they have to bear the risks of having large quantities of unsold stocks.

Further, the subsidies would encourage overproduction in terms of demand supply ratios, which could not be sold in normal market operations and it would become necessary to engage in dumping practices, thus being sold below the cost of production. This dumping may create further problems in the country where the goods are dumped and act to the detriment of the local economy, since local goods may not be able to sell at the cost of dumped goods.

Hence, a lot of small and marginal farmers would be rendered bankrupt due to such activities. It is seen that “each tone of UK (and EU) wheat sold on international markets sells at about 40 per cent below the cost of production – in other words, it is dumped. As demonstrated by ActionAid.s case studies in Pakistan, Nigeria, Indonesia and Bangladesh, this is having a detrimental impact on farmers and food security in developing countries.” (Farmgate: The developmental impact of agricultural subsidies).

In this connection it would be relevant to mention about the Common Agricultural Policy (CAP) which has evoked a lot of justified criticism since it is responsible for maintenance of high price of goods and also controlling the quantity of agriculture produce of its member states. Basically, the Common Agricultural Policy is a fund in which all member countries contribute funds which is next allotted by the EU among the farming community of countries. “Member states have to contribute to a central pool, which the EU then divides, as it sees fit. Some of these subsidies are actually paid to farmers to stop them farming their land, in order to keep the amount of food on the market low and therefore maintain a good price for food.” (European agricultural policy. 2007).

There are a lot of controversies raging regarding the effectiveness of the CAP and how it really helps in the economics of countries. It is seen that in the event of the scrapping of CAP, the largest beneficiary would be the USA, since then, it would be able to dictate terms to the member countries and also impose other conditionality. It is further seen that the countries that receive financial assistances and loans from leading international lending bodies like IMF, World Bank, etc, would also need to conform to their terms and conditionality including those regarding buying of agricultural produces and other regulations. Thus, the developing countries lose their economic independence and right for self determination in economic matters and have to concede to the loaner’s demands.

It is also possible that these world bodies may change the terms governing the loans to suit changing business climates and conditions.

It is also relevant to quote in this context, the ideas imparted by the legendary economist , Adam Smith in his 1776 classic book , the Wealth of Nations in which he expressed that although it is the intention of governments of countries to increase exports and reduce imports, sometimes the reverse also happens in that system is constrained to dissuade the export of raw materials in order to facilitate benefit to their workers to undersell these materials of other countries, and similarly, it sometimes happens that the system is perforce to encourage imports of materials into the country in order that the local workmen could make finished goods out of them and thus obviate the need for such finished goods to be imported into the country. (Shah 2007).

A report on the developing countries vis-a vis the World Trade Organisation by the IFPM is suggestive of the fact that at the Doha talks, the developing countries had taken a two pronged strategy- one of aggressive strategy by seeking to restrain the legal framework within which the developed countries could use under the current WTO rules to subsidise their agricultural sectors and seek protection for their own domestic industries has the second one, a defensive posture aimed at seeking protection and subsidies for their own industries. (Bonilla & Gulati 2003). It needs to be emphasised that the developing countries need to persuade the developed countries to pass on a part of the subsidies and benefits derived by them for the cause of development of the developing nations, and also seek greater protection for its domestic sector in order build a stronger economy.

Unless the urgent problems confronting the developing nations, in terms of feeding and nourishing its people are met, its negotiations with the WTO or at any public forum would not serve any gainful purpose. It also needs to be emphasized in this context that all developed countries seek their own advantages in the negotiating table, and unless the developing countries are able to impress upon the latter that it would make economic sense to invest in developing countries, no worthwhile purpose could possible be served through protracted negotiations like the DOHA talks etc. It is necessary for developing countries to take up their viewpoints in order to emphasise the need for mutual beneficial interests.

Beneficiary region: “Given the high binding overhang of developing countries, even with their high tariffs – and even if tiered formulae are used to cut highest bindings most – relatively few of them would have to cut their actual tariffs and subsidies at all. That is even truer if “Special Products” are subjected to smaller cuts. Politically this makes it easier for developing and least developed countries to offer big cuts on bound rates.” (Agricultural Market Access: The Key to Doha Success. 2005, p.2).

Conclusions

Ultimately, we can see that all researches & studies have proven that there can be a better world to be gained from liberalizing merchandise, especially agriculture sector, which can be achieved by combined operations & understanding between the developed and developing countries by taking care of matters effecting trades such as subsidies, tariffs and other trade barriers. We can see that most of the developed countries may not be agriculture based and are industrialised, therefore their operational thrust would be in terms of creating a stronger industrial base and generating profits and growth avenues for its industries.

Whereas the developing countries are mostly agriculture oriented and the majority of people are living on the earnings of agriculture as also employment opportunities in some of the leading developing countries are through agriculture either directly or indirectly. Therefore, the developing countries while focusing on industrial growth and structural reforms should also look into growing aspects of agricultural providence and their developmental and social welfare schemes.

Bibliography

Agricultural Market Access: The Key to Doha Success. (2005). The World Bank Group. Trade Note. Web.

ANDERSON, Kym (2004). Subsidies and Trade Barriers Centre for International Economic Studies. Web.

ANDERSON, Kym (2004). Subsidies and Trade Barriers. Copenhagen Consensus. Web.

BONILLA, Eugenio Diaz & GULATI, Ashok (2003). IFPM: Annual Report Essay. Developing Countries & the WTO Negotiations. Web.

Economic Conditions in Developing Countries. (2008). Penn State. Web.

GODFREY, Claire (2002). How EU agricultural subsidies are damaging economies in the developing world. Oxfam: Stop the Dumping. Web.

Globalization, free trade, foreign trade. (2006).What have been the latest developments in the “globalization” controversy? Newsbatch. Web.

GILLSON, Ian et al (2004). Understanding the impact of cotton subsidies on developing countries. Web.

European agricultural policy. (2007). International Debate Education Association. Europe CAO 2007. Web.

Farmgate: The developmental impact of agricultural subsidies. What is the Farm gate Scandal? Action Aid. Web.

New research backs reform of EU farming subsidies. (2008). University of Aberdeen. Web.

Riddle, John (2005). Agriculture commodity prices continue long-term decline. FAO NEWSROOM. Food & Agricultural Organization of the United Nations. Web.

SHAH, Anup (2005). Food Aid as Dumping. Food Dumping [Aid] Maintains Poverty. Web.

SHAH, Anup (2007). Structural adjustment: A major cause of poverty. Causes of Poverty. Web.

Stockbridge, Michael (2006). Oxfam Research Report: Agricultural Trade Policy in Developed Countries during Take Off. Web.

Sweet sufferings. Undercutting export opportunities. Web.

The State of Agricultural Commodity Markets. (2004). Food and Agricultural Organization: FAO. Constraints in developing countries. P. 24. Web.

The gravy train rolls on. (2005). KICKAAS. Web.

Understanding the WTO: The agreements. (2008). Anti-dumping, Subsidies, Safeguards, contingencies, etc. World Trade Organization. Web.

World development report-2008: Agriculture for Development. (2007). World Bank Staff. Web.

Agricultural Market Access: The Key to Doha Success. (2005). Trade Note. P. 1. Web.

Agricultural Market Access: The Key to Doha Success. (2005). Trade Note. P. 2. Web.