Introduction

The snow on the mountain was melting and Bunny had been dead for several weeks before I came to understand the gravity of the situation. The same fate had befallen my other brother, Melville, just two years before Bunny. These subsequent events changed my conviction that the year 1870 was going to be a huge success to my family. This very morning I had no clue of what was going on until my parents informed me that we were going to leave Edinburgh, Scotland, in search of a healthier climate. It was a very short notice and since I had counted on working on my telephone project in the spring of 1870, I was at first not ready to move with my parents. I could not because most of my equipment and tools were stationary and I did not imagine starting afresh a project, which had started to illuminate some progress.

A year before this, it would have seemed possible since I had not done much on the project, but now it seemed like a terrible disaster. I had a good excuse to remain in Edinburgh and continue with the project, since I really valued it. Furthermore, I could not imagine leaving my good neighbors, the Ricks, and the serene climate that traversed the wooden neighborhoods of Edinburgh. I was confused and I felt compelled to make a decision in such a hurry. I walked inside the house and heard my dad calling out my name loud, “Come back here, Alex. We have to agree on this issue!” “Ok, I am coming dad” I answered. His tone was not usual and I knew he was becoming agitated. His face expressed a lot of fear and my mother was just quiet waiting for my positive answer. My dad expressed his fear of losing his only remaining son and he told me how much I meant to the family. Finally, I was convinced to move and experience life outside my childhood city.

From Edinburgh to Brantford

At this point, I had worked so hard to prove my worth to my family and the rest of my friends around me, but the fact that I was leaving Edinburgh made me feel disappointed and now I was retreating and not ready to prove anything to anybody. For my fallen brothers, I had a reason to fight and live long. Running from Edinburgh felt like withdrawing from this course, but for the sake of my good relationship with my parents, time was due for us to move together as a unit (Shulman, 2008).

During this time, I had no money because I depended on my parents for livelihood and my project. It could have been hard staying back against their will. I had become very friendly with my neighbors so I took a few minutes to say goodbye as my mother helped dad to load our luggage in an old Volkswagen. Rick could not believe we had decided to move on such a short notice. I tried to explain the situation before I hesitantly said goodbye. Within less than half an hour, we were ready to depart for Brantford, Ontario. The spring of 1870 was now marking a fresh beginning in my life. Although, I had not dreamt of leaving Edinburgh, the new climate in Brantford felt more serene. From the first glance of my new town, I realized that I was going to catch up quickly and pursue my dreams of improving the state of communication for all.

Like most of the residential buildings constructed in the1870s, our new house assumed the Queen Anne style with a verandah and several rooms where each family member could find some privacy and silence. The house had a tower and it was so colorful. The entire neighborhood looked like a pattern since the building design was similar in Brantford for the middle classes (Lawson, 2008).

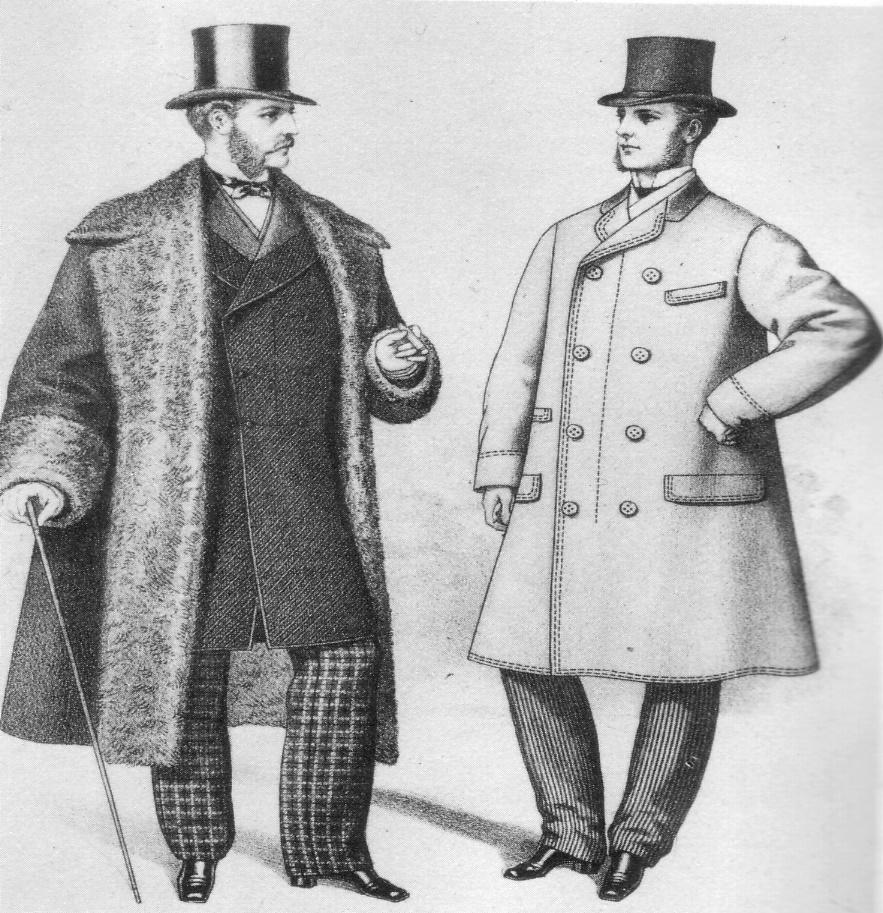

The low-class families lived in well-furnished wooden houses with little open spaces where they planted some vegetables. From the types of cars and houses, it was easy to tell that the middle-income class occupied Brantford. At this time, the climate in Brantford was very cold since winter was in its closing stages. People dressed heavily using warm clothing like woolen coats, scarfs, hats, and gloves. People covered all parts of their bodies to protect themselves from the chilly weather (Lin, 2012).

I found Brantford a little bit colder as compared to Edinburgh, as I had lighter clothes than this new climate demanded. Since I knew that the spring was on the way, I did bother buying new clothes because it would introduce a gradual return to warm environs.

Changing attitude

I knew I needed not only my parents, but also new friends, teachers, and colleagues to help me with my project. Apparently, I had to do many things by myself until I learned that my parents had decided to move following Henderson’s invitation, who was a Scottish friend and a Reverend who had moved earlier to live in Brantford. I now learned that I had someone who would help me adjust quickly to life in the wider Ontario.

My college education and teaching experience would not have been of great effect without the encouragement of friends, inspiring conversations with my father, and now my new friend, Henderson. Partly due to the experiences that had compelled my family to move on that chilly morning in March and the events that followed, I was now finding new horizons. From my new environment and relation with Henderson, I developed the desire to connect my earlier project with real life situations, which could touch people in great ways. My interaction with Henderson made me question my own adaptation to Brantford. Was my own adaptation to this new environment typical? I really did not struggle as a newcomer. I learnt that Henderson had known much from my father and organized a teaching opportunity for me to teach deaf students at a local institution and later in Boston.

As I continued to interact with this new environment, I came across different people in disparate places around Ontario. The majority of the places were fascinating, but Henderson made it easy for me until I realized I had developed a close friendship with him. After a long walk through the neighborhoods, I realized that I was gradually finding something outside myself that gave much meaning to my life than I had previously thought. I had loved working in my deserted workshop all day with only my parents getting involved at times, but now it seemed I was establishing the passion for working with the community. Having previously taught visible speech at a London private school of deaf children owned by Susanna Hull, my father’s friend, I felt motivated to take the offer that Henderson had organized for me.

At one point as we walked back home, I nearly introduced the topic, little did I know he was going to ask me about the offer before I could engage the conversation. Henderson carefully reached out my hand and called out my name quietly, “Alex, have you thought of the offer to teach at the community school of deaf children.” “Yes. I am willing to take this new challenge.” I answered (Gray, 2006, p.14). From deep within, I strongly felt that I was doing the best thing not only in my life, but also for my community.

Disturbing thoughts

Life in Brantford was changing faster than I had imagined. Even though the weather was giving me some problems, I felt safe since I had moved away from a place where I had witnessed my siblings succumb to tuberculosis. I was swiftly getting used to heavy clothes as well as having more time with friends. I had agreed to commence teaching on the following morning since my services had been long awaited although I was not aware. March 3, 1870 was to mark my first encounter with deaf children in Brantford. Since I was not used to socializing with people often, I knew I needed to perfect my presentation skills.

Early that morning before meeting Henderson for orientation, I passed by the hairdresser. The hairdresser gave me a warm welcome and said, “My friend, can I help you?” “Yes,” I responded. “Will you please cut my hair short and wash my head?” “Right away,” he answered. He was a nice charming person and within a short while, he had done his job just as I wanted. I hurriedly walked towards Henderson’s house where he was patiently waiting for me. This moment was an opportunity for me to link with people beyond my neighborhoods by interacting with children from diverse origins, but with a common need. By now, I had no clue that this event was going to build on my telephone project, which I had put on hold for some time.

Everyone in the Brantford deaf institution appeared very understanding and welcoming. I did not feel like a stranger as Henderson had worked everything out for me. Although I had left the security of my former comfortable workshop to share my knowledge and advance my ability through teaching in diverse communities of deaf students, a lot of courage was swiftly building from inside. I did not know this beginning would later mean a lot to my life.

I had always believed that my destiny would be solely determined by my passion for inventing a communicating device. With my little experience with deaf children, I made my first speech about how everyone can understand and communicate using symbols and how I was determined to help my new students to learn. At this time, I was not even sure if the students were in a position to understand my visible speech. It was a big challenge, but just as my father had flourished in this field, I was keen to follow his footsteps. I was keen to pioneer the visible speech, an idea developed by my father to help the deaf-mutes and speech-impaired children. I had long been fascinated by the concept of transmitting speech and I knew I stood a better chance of actualizing this aim by interacting with speech-related problems (Royston, 2010).

That morning was my first day teaching in Brantford community school for the deaf children and it marked my second encounter with a class of deaf children. At this point, it started to appear as if we were not off on the right footing. One of the students attempted visual conversations implying that he disliked visible speech and he was not ready to cooperate. I composed myself and assured the children that I was going to be friendly to them and help them learn visible speech. Visible speech included a system of symbols to assist deaf individuals in speech. This aspect was not common in Brantford, but it was a source of hope for the deaf and speech-impaired children.

Teaching the virtues and successes of visible speech was not going to be easy as I first thought. Although students seemed to understand some of the ideas of visible speech, the students did not express concerns to let me know which parts of visible speech confused them and the kind of assistance they required in a bid to improve their speech. Nearly an entire class of angry faces confronted me that day. This move was just but an insight of what awaited me in this new course that I had chosen to endeavor. This institution consisted of deaf students representing diverse cultures and a wide range of social classes (Carson, 2007). Since Ontario was a city of immigrants, I anticipated such experiences. Since most of the students came from low-income backgrounds, I felt obligated to help them and create an impact in their lives.

Building confidence

During my first lesson, the situation was highly complicated, but I was not ready to withdraw. On the contrary, I focused on overcoming all barriers. At the end of my first lesson, I summoned a boy who had demonstrated an extreme lack of interest in this lesson. “Jack, right?” I asked using symbols of which I was not sure he understood in the first place. “Yes, so what?” he implied using visible speech. Although the response was not perfect, I was fascinated to realize that there was a chance to develop from somewhere. “Listen, I surely understand each student’s feelings about visible speech. I have joined you to assist everyone to learn how to communicate successfully.

Kindly do not let any obstacle come your way while I can help.” I affirmed this using visible speech. Jack smiled discouragingly at me as he walked out of the class. I knew I would find a way to engage him, which would serve as a breakthrough to creating rapport with other students. Whenever I felt like quitting, I would experience memories of my deceased brother, Bunny. I had to do everything possible to achieve what my family had set to achieve. By now, I had realized that my father had moved us from Edinburgh so that I could see the maturity of the family dream in helping deaf children learn how to communicate successfully.

Despite the inspiring support from my parents and Henderson, I never saw myself developing personal ability in my current role. At one point, I solely wanted to help and never thought of myself for a second. I was not sure how long this feeling would last. I spent an entire evening attempting to figure out how wrong I had approached my first lesson in this new institution. Everything seemed normal so I had no basis to complain. I knew I needed time to learn how to engage my class.

My anxiety from being a prospective teacher to conducting my first lesson had now declined since the reality had hit me hard. I spent the best part of that evening trying to see how I could set up my telephone project and divert my thoughts from the school experience. Unfortunately, I had to get new materials to set up a new station, but I did not know how since I had not saved any money for this project. Henderson had taught me to take everyday situation as a basis to build a better tomorrow. This aspect reminded me of the new horizons that I was starting to join. Each new day, I had the opportunity to interact with new people who played a significant role throughout the process whilst presenting a broad range of expectations and experiences.

Helping the deaf children learn visible speech was not an easy or pleasant experience as I thought, but meeting students like Jack for a second time felt scary. One of the hardest things I was yet to learn was being tough. I was always keen not to hurt anybody, but I decided that helping these students was very necessary and nothing was going to stop me. What I realized was that acting tough would also build my confidence in all my objectives. The two weeks following my brother’s death kept lingering on my mind. Mentally and emotionally, I got the taste of real life. Now I thought of pursuing what my brother cherished, viz. helping the deaf children, but I felt lacking in my approach.

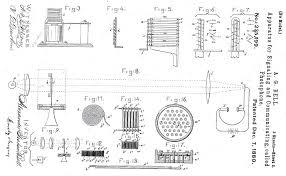

My father was always there when I sought his advice, as he had a lot of hope in me. For the first time, I wanted to be on my own doing what I felt was best for my students. I decided to relate my classes with my project and see how I could help the deaf students. In the evenings after school, I would spend a little time in my newly set station. I started experimenting with electrical signals in an attempt to invent a telephone device. However, I realized that whenever reflecting on my project, the skills that I had learned from my father never crossed my mind. On the contrary, there were memories of everyday dreams that my late brother, Bunny, wanted to achieve for the deaf children. Unfortunately, I did not realize that I was at one time going to be accredited for inventing the telephone, which my father and I had always thought of in our lives.

The great invention

By the summer of 1870, I had worked with two schools for the deaf and this felt little of what I looked forward to attaining within my first year in Brantford, Ontario. The spirit of invention had possessed me and motivated by the urge to benefit the world, I sought to improve life through communication. I always looked at the situation in Ontario and with the breakthrough I had helping deaf children learn how to communicative using symbols, I was convinced that this was not enough to improve the lifestyles for all people. I had a strong feeling that my harmonic approach was viable to invent a device that could transmit signals from one end to the other. My childhood interaction with my grandfather who often liked experimenting was in a short while going to prove vital. By the end of 1870, the idea of the telephone became so vivid.

At this time, I had invested a lot of time and money on this project and I experimented with a system that could relay several message at the same time through a single wire. As I taught, I also experimented with different devices to assist the deaf learn to communicate. Eventually, on December 14, 1870, I came up with the first telephone device. With the help of my assistance, Lucy, we made the first conversation over the phone. Within a short while, the news had spread everywhere through the same device that I had invented. By the eve of the New Year, many families in Ontario had acquired a telephone device (Grosvenor & Wesson, 1997). At last, I realized that I had achieved something for my family and community.

Conclusion

As I constantly embarked on perfecting my device, I tirelessly committed my time to help the deaf children to improve their integration into the mainstream community with the means of lip-reading and alternative techniques. Despite the fears that developed at the beginning of the year, losing Bunny was surely a turning point in my life. This year defined my entire life and it remains fresh in my mind.

Figures 3a & 3b show that only a few people owned cars with most of the middle-income earners opting for horse-ridden caravans, which were deemed prestigious. Availability of motorcar and road network facilitated Moving from Edinburg to Brantford. Fig. 4

Figure 4 shows the kind of weather experienced during nights in Brantford. Adapting to this kind of climate is not hard since Edinburg and Brantford had relatively similar weather patterns.

Figure 5 shows the environment in Brantford. The climate is admirable and welcoming though it is a bit chilly.

Figure 6 family life was always cherished in during 1870s in Brantford. Having close family ties facilitated networking which helped cope with new neighborhoods and social integration.

Figure 7 demonstrates the telephone project that was part of my daily involvement

Figure 8 demonstrates an accomplished telephone project that changed lives of many people. To me, this was a dream come true and a dedication to my family whose support was reflected through the project.

References

Carson, M. K. (2007). Alexander Graham Bell: Giving voice to the world. New York, NY: Sterling. Web.

Gray, C. (2006). Reluctant genius: Alexander Graham Bell and the passion for invention. New York, NY: Arcade Pub. Web.

Grosvenor, E., & Wesson, M. (1997). Alexander Graham Bell: The Life and Times of the Man Who Invented the Telephone. New York, NY: Abrams. Web.

Lawson, D. (2008). Posterity: Letters of great Americans to their children. New York, NY: Broadway Books. Web.

Lin, Y. (2012). Alexander Graham Bell and the telephone. New York, NY: PowerKids Press. Web.

Royston, A. (2010). Inventors who changed the world. New York, NY: Crabtree Pub. Web.

Shulman, S. (2008). The telephone gambit: Chasing Alexander Graham Bell’s secret. New York, NY: W.W. Norton & Co. Web.