Description of the movement of US Current Account and Budget Deficits in Since 2005

The current account tracks the flow of goods, services, income, and transfer payments into and out of a country. The figures of the current account balance for a particular year are an indication of how a given country’s economy has interacted with other economies around the world in terms of exports and imports of goods and services, unilateral transfers (such as taxes, one-way gifts, and taxes), and income payments (such as dividends, salaries, and interest) (Trading Economics 1).

The Current Account, along with capital account and financial account, is a fundamental determinant of the magnitude of a country’s Balance of Payment (BOP); which summarizes all international trade transactions a country engages in as at a particular point in time, or over a particular period. The current account tracks that part of international trade involves goods and services, unlike capital and financial accounts which deal with the flow of investments as well as financial assets.

A positive balance in the current account (a surplus) is an indication that the flow of goods and services into a country (imports from its trading partner or partners) is less than the flow of the same out of the country (International Monetary Fund (IMF) 6). On the other hand, a negative balance in the current account (a deficit) is an indication that the country imports more goods and services from the outside world – or a particular trading partner – than it exports to the same.

The United States accounts for the largest volume of international trade. It has consistently occupied the leading position when it comes to the volume of imports and, similarly, it has continued to be among the top three exporters in the world. However, for the past few decades, the United States has been recording large deficits in its current account mainly due to significantly large deficits in its trade balance with foreign countries such as China.

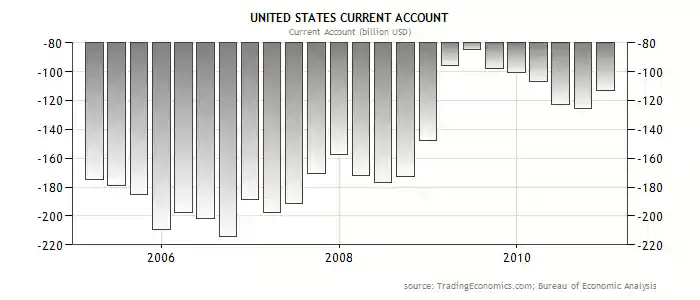

For the first three months of 2005, the US trade account deficit stood at $198.7 billion, which represented the largest shrink in the current account deficit in a single quarter within the previous four years. In the rest of the year, however, the current account deficit went back to the previous deficit expansionary path, with the third and fourth quarters witnessing the deficit hit $195.8 billion and $ 197.8 billion respectively (Trading Economics 2).

The unexpected narrowing of the deficit, especially between July and September, was credited to an upsurge of insurance payments to victims of Hurricane Katrina as well as donations to the same course that poured into the U.S from abroad.

The deficit continued to widen because the demand for imported goods was still matching upwards driven by an expansion of the economy. The country’s demand for crude oil, televisions, and autos was increasing, too. Therefore, the first quarter of 2006 saw the current account deficit reach $857 billion despite significant growth in the last quarter of the year. This represented a further annual expansion of the deficit; by $67 billion more than the deficit for the previous year, or 8.2% of the previous year’s deficit. The current account deficit for 2006 represented six and a half percent of the county’s GDP, which essentially meant that the country produced 6.5% fewer goods and services than it consumed in the same year (Cline 2).

In the first quarter of 2007, the current account deficit rose by about $5 billion in excess of the balance recorded in the fourth quarter of 2006 (Scott 1). However, the balance was below the figure reported for the same period in the previous year. At the close of the year, the current account balance stood at $708.5 billion, which represented a 6% improvement compared to the figures for 2006.

Net unilateral transfers to non-US citizens, which included grants by the US government as well as foreign remittances by US citizens or non-US citizens residing in the US, accounted for the largest part of the deficit in the 2007 current account deficit,. Moreover, an increased deficit in goods during the year also significantly contributed to the expansion of the current account deficit. Services trade, on the contrary, recorded growth in surplus over the same period.

The current account deficit declined to $673 billion in 2008 from 2007’s figure of $708.50billion. This was partly due to a slight increase (from $819.4 billion registered in 2007 to $820.8 billion) deficit on goods (Trading Economics 1). As such, there was a significant increase in net exports as exports grew slightly more than imports into the U.S., and this was the second time in a row that the deficit was recorded to have improved. Net unilateral current transfers to foreigners also fell, thus contributing to the decline, as did the expansion of surplus on income over the same period.

In 2009, the current account deficit of the United States declined rapidly to $378.4 billion from a deficit of $673 billion in 2008 (CIA 1). This was the smallest deficit in a decade. In 2009, the major factors that contributed to a sharp decrease in the current account deficit were: a sharp decline in the deficit on goods due to a more rapid decline in United States’ imports than its exports, a considerable surplus on income as well as a similar surplus on services, and a sharp increase in net unilateral current transfers to foreigners.

By the end of 2010, the current account deficit had taken an upward turn yet again and stood at $470.2 billion (Carbaugh 445). This was the first time that the deficit had risen (in regard to a yearly basis) since 2006, and the major factors that were attributed to the increase ware; a huge increase in the deficit of goods, as well as a spike in net unilateral current transfers to entities outside the United States.

United States Government Budget Deficit

Government budget can be described as an itemized accounting of the payments received by the government, from such sources as taxes, levies, licenses, and other fees, and all payments made by the government in such activities as government purchases as well as transfer payments. A budget surplus is said to occur when government receipts exceed its planned expenditure, whereas a budget deficit occurs when the planned government expenditures are more than payments received by the government.

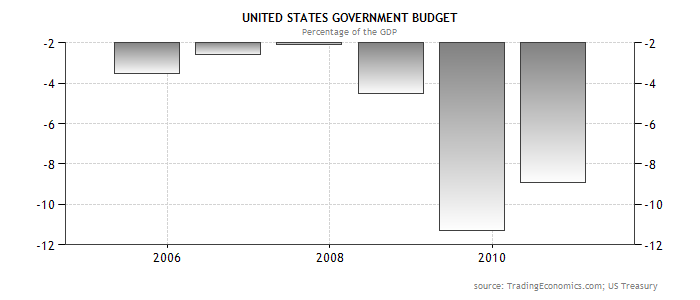

Since 2002, the US government has consistently been running a deficit budget. For the years 2005 through the beginning of 2011, federal deficits have been as follows: $318.6 billion, $248.6 billion, $170.0 billion, $ 458.5 billion, $1,452.7 billion, and $1,555.6 billion respectively (Trading Economics 1). The figure planned for 2011 is 1,266.7 billion. For 2010, the budget deficit was equivalent to nearly nine percent (8.9%) of the country’s GDP.

The link between U.S Current Account Deficit and Budget Deficit

From the above historical data, it is evident that both the current account and budget balances move in the same direction. Because a current account deficit indicates that a country is importing more than it is exporting; that is, it is consuming more than it can produce, it follows that the government has to borrow mainly from external sources in order to fund the excessive expenditures it incurs in the provision of public services.

Policy Options for Reducing US Current Account Deficit

In 1980, the U.S had a small surplus in its current account. However, beginning 2001, the U.S current account has been operating with negative balances which keep growing almost on yearly basis, such that the country now has one of the largest deficits in the world.

A negative balance in a country’s current account is of serious concern to policymakers who view a large deficit in the current account as a recipe for the increased likelihood of the country experiencing a recession, reduced national saving, as well as intensified pressures for implementation of protectionist legislations.

The U.S government has two tools with which it can try to reduce the negative balance in its current account: using monetary policies or fiscal policies or both.

Many economic analysts believe that fiscal policies are the most effective in reducing current account balances than monetary policies (Congressional Budget Office (CBO) 29). The reason for the inappropriateness of monetary policies in solving the problem of current account deficits comes from the fact that monetary policy actions tend to produce offsetting effects on the external balance. For instance, a monetary policy that restricts the amount of money circulating in the economy has the effect of lowering aggregate demand which then makes the balance in the current account to improve due to a reduction in personal incomes as well as a similar reduction in the demand for exports.

However, this desired effect is eroded by the gains made by the country’s currency that automatically follow the constriction of the money supply. Higher interest rates produced by the reduction in money supply attract foreign investments, which worsens the balance in a country’s current account by means of diverting expenditures on locally produced goods and services to imported goods and services (CBO 23). Thus, the net impact of using monetary policies in trying to reduce current account deficits is likely to be insignificant.

Using fiscal policies to reduce a negative balance in the current account

Most analysts agree that the current-account deficit is best tackled by the use of fiscal policies that aim to reduce domestic spending, or “absorption”, through increased national savings. National or public savings can be increased by adopting austerity measures that significantly cut back on government or public spending; that is, reducing the budget deficit (Carbaugh 433). Hence, fiscal austerity or restraint has the impact of improving the current-account deficit through effectively reducing personal as well as corporate incomes and devaluing the currency.

By March 2011, the United States had accumulated over $14 trillion in national debt, and the figure is projected to continue rising in the future. There are many disadvantages to running a national budget largely on borrowed funds as is the case currently with the US government budget. Generally speaking, the government is – partly – economically undesirable for it engages the private sector, which is a much more efficient producer, in a competition for the scarce resources of a country and, as a matter of fact, almost always emerges as the winner in this duel for economic resources; thereby harming the economy.

This, almost naturally, calls for drastic measures to attempt to reduce – if not to eliminate – the huge budget deficit. This can be done through either or both of two fundamental actions: increase government revenue and/or cut government spending.

In the case of the United States, efforts to lower the country’s budget deficit are complicated by the large number of programs run by the federal government, as well as the complex tax code that exists in the country, plus many politically driven funding decisions rather than decisions driven by economic sense (Stocks Market Today 1). These complications, however, do not mean that it is entirely impossible to significantly cut back on US government spending and thereby reducing the huge deficits recently characteristic of US government budgets.

One of the most effective and readily available tools for manipulating the revenues of the government is taxes. The government can decide to raise either all categories of taxes or just a few taxes, in order to raise the amount it receives as tax revenue. It can decide to raise the tax rates on personal income, dividend earnings, capital gains, corporate profits, as well as the rates chargeable to inheritances. Another fertile area from which the federal government can raise a significant amount of tax revenues is tariffs. Although an increase in the rates of tax on imports or exports can bring about frictions with trading partners, the government can effectively raise the rate of taxes on a specific category of imports as well as exports.

Nonetheless, the option of raising tax is not easy. Many analysts oppose this option on the basis that high tax rates have a considerably substantial negative impact in that they reduce incentives to work, save, as well to invest. In this regard, therefore, the most appropriate approach to reducing the budget deficit is the federal government embarking on policies that significantly cut back on excessive public expenditures.

Reduce Entitlement Spending

One of the areas in which the federal government is accused of spending a little too much is entitlement spending. The federal government’s expenditure on such entitlement programs as Medicaid and Medicare, which are designed to provide health care services to particular groups of people in the society, including elderly citizens, low-income earners, teen mothers, as well as the disabled, has been widely criticized as being unnecessarily too high (Riedl 2).

The government should, therefore, seek appropriate ways to cut back on the amount allocated to these programs. For instance, it can revise upwards the age at which retirees become eligible for receiving elderly benefits, and/or lower the number of benefits available in these social welfare programs. The huge wastages reported in the programs’ operations need also to be reduced. This way a lot of costs would be saved which, in turn, would go a long way in helping reduce the large funding gap in the US national budget.

Cutting back on non-defense discretionary spending

In 2011 alone, The Pentagon has been allocated $700 billion of taxpayer’s money to run the U.S security apparatus (Riedl 1). Despite U.S national security ranking topmost among the priorities of US government spending, there is a huge room for exercising austerity measures in military expenditure. For instance, the United States has military bases in addition to keeping a sizeable number of troops in several regions of the world which are currently quite stable, like South Korea, Japan, and parts of Europe. A significant reduction in the number of these bases and troops would most likely not jeopardize U.S national security, and the savings made from reduced maintenance costs would go a long way in reducing the deficits in the current account.

Also, a sizeable chunk of the country’s military budget is used in the research and development of advanced weapons and weapon systems. Given the current superiority of US military hardware as well as software compared to that of countries perceived as US enemies, plus the fact that no major war involving the U.S is foreseeable in the near and middle-term future, a sizeable cut on the taxpayers’ money spent on financing weaponry development programs would be in order, and would also help reduce the current account deficit by a significant margin (Riedl 3).

Cap farm subsidies for farmers

The US government allocates in its annual budget roughly an equal amount of money to corporate welfare as it does to homeland security. Subsidies to American farmers form the largest portion of this corporate welfare, yet questions have always arisen as to the economic sense of such massive programs in the same way they have arisen concerning the real beneficiaries of the programs. These programs are repeatedly heavily criticized for attempting to bankroll economically unsustainable overproduction by U.S farmers as well for driving down farm produce prices downwards. They are also, more importantly, blamed for benefiting wealthy farmers as opposed to helping modest and struggling farmers they are meant to help (Cook 2).

It is estimated that if the programs were efficient enough and catered only for the modest and struggling farmers, then an annual amount of $4 billion would be enough to run successful subsidy programs, which means the government would stand to save $70 billion in subsidy costs over the next ten years, and at the same time strengthen the economic stability of American farmers (Cook 5). The introduction of subsidized crop insurance could also help cushion farmers against weather hence crop yield fluctuations.

Why the Chinese authorities are willing to finance US profligacy

Over the last decade, the Chinese economy has been experiencing exponential growth, and it is only natural that the country has been accumulating huge budget surpluses over the same period. These large surpluses are mainly due to China’s current account balance, which is largely positive since China exports far more goods and services than it imports. On the other hand, United States’ has been running a twin deficit for nearly one decade now, and China has been one of the largest lenders of funds needed to fill the gap in the U.S government budget left by overspending (Swartz and Steil 1).

Chinese interest in the US treasuries and bonds is multifaceted. First, the U.S is China’s biggest foreign market for goods produced by its booming industries. The US does not just provide China with a considerably large market for its goods, its consumer market – more importantly – is wealthy and it is willing to spend much more than it earns; which help soak up a considerably large chunk of the output of Chinese firms in addition to helping create employment in China, hereby helping sustain social stability in the country; Chinese authorities’ single most important objective. As a matter of fact, China’s exports to the US outstrip its import volume by nearly five hundred percent.

One important element of the US-China bilateral trade is that a considerably large portion of Chinese goods purchased by the US has been- and continues to be – done on credit. Therefore, a significant amount of the debt the US owes China comes from goods and services sold to the US by China (Swartz and Steil 3). China would not, therefore, just sit around and watch the US economy tumble because if it did China would have a lot to lose, too.

Perhaps the biggest reasons why the Chinese continue to fund the United States’ rapidly growing twin deficit is the safety, stability, and liquidity of investments in US treasuries. Historically, there has always been a very low risk of the US government defaulting on its loans. In addition, investments in the US government bonds have historically generated fairly stable yields largely due to the stability of the value of the dollar. On the other hand, the Euro and the Yen markets (the other options for Chinese investments), often record significant currency fluctuations depending on the prevailing economic cycle.

In addition, no other countries have deficits in their national budget as huge as that of the US budget, which makes them too small to sufficiently soak up China’s huge trade surpluses, thus making their home government’s treasuries significantly unattractive investments (Swartz and Steil 3). Investment in gold is another option for the Chinese, but such investments do not bear interest and are not liquid, not to mention that the gold market is too small to accommodate Chinese trade surpluses. Thus, in sum, US treasuries are the most viable option for investing in China’s budget and current account surpluses.

The United States economy benefits from running trade deficits in the long run as long as the Chinese monetary authorities continue to buy U.S treasuries

In the recent past, the U.S. economy has been going through tough economic times. The 2007 subprime mortgage crises and the 2008 global economic recession hit hard the economy particularly hard. As a result, the government was forced to incur huge loans from both the domestic and the foreign markets in its subsequent years’ budget, as it could hardly raise the number of funds required to run its public programs from the traditional revenue sources.

Arguably, fiscal policy measures provide the most appropriate approach to lifting a country’s economy from stagnation or recession. In this respect, the US government has deliberately attempted to boost consumer demand and steady the turbulent market in the country through massive public spending programs, such as the massive bailouts of investment banks and other financial services institutions faced with imminent collapse due to the collapse of the subprime mortgage market that began in 2007. The bailout commitments now stand at an estimated $9 trillion since the onset of the credit crises in 2007 (Wang 3).

Considering the above facts, the U.S economy is in dire need of capital injection to stimulate consumer demand. Fortunately enough, the U.S has China to turn to; China boasted of having an estimated trade surplus of $ 272.5 billion by the end of 2010 (CIA 1).

Although some analysts have argued against U.S. dependency on foreign debt – more so from the Chinese – for the reason that countries holding US treasuries could collude and attempt to bankrupt the US economy by selling the treasuries they hold on a large scale and within a short period of time, the funds secured from foreign debts are extremely useful in boosting the ailing US economy; much more than the underlying risks in the loans. For instance, loans and mortgages underwritten by foreign debts cause mortgages market rates of interest to go down in addition to allowing the introduction of flexible terms of credit.

Therefore, as long as the Chinese are willing to continue investing in the US treasuries, which is the most probable case for they have no other significantly material alternatives besides the fact that the Chinese almost certainly are unlikely to offload their huge US treasuries’ holding for the reason that they too have a lot lose if they did so, the US government is in an order running twin deficits (Wang 4).

The currency regime adopted by China Since 2005

From 1994 up until July 2005, the Chinese monetary authorities pegged the value of the Renmimbi (RMB) to that of the US dollar (Morris and Lardy 8). Since July 2005, China shifted its currency regime to a tightly controlled, partially flexible exchange rate regime; whereby the value of the RMB would henceforth be calculated against a basket of selected currencies from China’s top eight trading partners and not just the dollar.

At the date of the currency regime shift, also, Chinese monetary authorities set the value of the Yuan against the US dollar at ¥8.11 for 1 US $, and the value of the RMB would henceforth have a very narrow band in which it could fluctuate within in any two consecutive days of trading; 0.3 lower or above. The change in the currency regime was partially due to increased pressure for China to free up the Renmimbi from the US; which the latter felt was hugely undervalued thus creating unfair trade imbalances between the two countries, and which greatly favored Chinese exports.

The currency regime adopted by China, as opposed to falling squarely in either fixed or flexible exchange rate, is a mixture of both. The fact that the value of the RMB can fluctuate, albeit very minimally, depending on the market conditions gives it some significant features of a currency with a flexible exchange rate, whereas tight control of the value of the RMB by Chinese monetary authorities makes it a currency with a largely fixed exchange rate.

Advantages and disadvantages of China’s exchange rate regime

China’s exchange rate regime is cited to bring several benefits. To begin with, keeping the value of RMB largely controlled and at a significantly lower value has the impact of lowering production and operation costs for Chinese firms because purchases of raw materials and components priced in foreign currencies in the international market costs Chinese firms as well as multinationals corporations based in China much less than their counterparts located in other parts of the world. Moreover, the currency regime adopted by China tends to shield an economy from asset bubbles and inflation much better than a flexible exchange rate regime.

However, a fixed exchange rate regime means that the government is constantly meddling with interest rates in the market by buying and purchasing its own currency in order to maintain its value (Wang 2). This requires it to keep large reserves of foreign currencies to be able to effectively trade in the exchange market. Moreover, a country may resort to raising interest rates if it feels that its currency’s value is headed downwards, which may produce inflation.

Furthermore, it is difficult to manage the exchange rate of a currency because there are many factors, other than interest rates, that is constantly changing and which act simultaneously to determine the market value of a currency (Carbaugh 466). Finally, undervaluing a country’s currency could most likely than not cause friction between a country and its trade partners, like the case has been between the US and China for quite some time now.

Works Cited

Carbaugh, Robert. International Economics, 12th ed. Mason, Ohio: South-Western Cengage Learning, 2008.

CBO. “Policies for Reducing the Current-Account Deficit.” Congress of the United the United States. 1989. Web.

CIA. Country Comparison: Current account balance. n.d. Web.

Cline, William. The United States as a Debtor Nation. Washington: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2005.

Cook, Ken. “Government’s Continued Bailout of Agribusiness”. Farm Subsidy Database. Environmental Work Group. 2009. Web.

IMF. World Economic Outlook Database April 2010 Washington: International Monetary Fund. 2010. Web.

Morris, Goldstein, and Nicholas Lardy. The Future of China’s Exchange Rate Policy. Washington, DC: Peterson Institute for International Economics, 2009.

Riedl, Brian. The Five-Step Solution: Cutting the Budget Deficit in Half by 2009 While Extending the Tax Cuts and Rebuilding Iraq and Afghanistan. The Heritage Foundation. 2005. Web.

Scott, Robert. “International Picture: March 14, 2007.” Economic Policy Institute. 2007. Web.

Stocks Market Today. Bernanke Urged Congress To Act To Reduce The Budget Deficit On Wednesday. 2011. Web.

Swartz, Paul and Benn Steil. Dangers of U.S. Debt in Foreign Hands. Council of Foreign Relations. 2010. Web.

Trading Economics. U.S. International Transactions: Fourth Quarter and Year 2010. 2011. Web.

Trading Economics. United States Government Budget. 2011. Web.

Wang, Jian. “With Reforms in China, Time May Correct U.S. Current Account Imbalance”. Federal Reserve Bank of Dallas. 2011. Web.