The number of working women in the international labour force continues to grow. In the recent years, more women with young children have decided to re-enter the labour force. According to Lavery (2012), the share of working mothers with children under age 6 has risen sharply against the overall state of the labour force.

High labour force participation rates for women with children aged below 6 years are associated with “the recent economic recession, the steady decline in men’s real earnings, the growth in single-mother families, and the increase in women’s educational levels” (Lavery, 2012).

However, the main question is not in why so many mothers choose to work but in whether at all women with small children should work. This is the question of opportunities and costs, which has profound implications for women’s and whole societies’ economic and social development.

The existing theoretical and empirical models suggest that women who enter paid labour force when their children are still young face better wages and improved career growth opportunities; government policies that guarantee universal and affordable day care, increase women’s wages and reduce their paid parental leaves create strong incentives for women with young children to get back to paid work.

Working Women with Young Children: Statistics and Trends

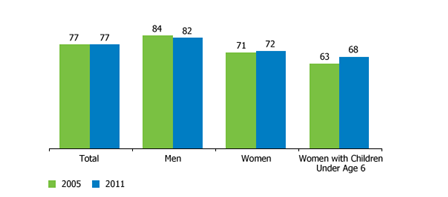

The number of women who enter paid labour force after childbirth has increased substantially over the past years. This trend is similar across most European countries and the United States. In the United States, the percentage of working women with young children (under age 6) increased from 63 percent in 2005 to 68 percent in 2011 (Lavery, 2012).

The graph shows the growing percentage of working women with young children in the U.S. workforce.

According to Hayghe and Bianchi (1994), the patterns and experiences of working women vary considerably, depending on the age of their children: school children tend to spend most of their time at school and do not require as much supervision as younger children.

In Europe, especially Scandinavian countries, governments welcome women’s increased participation in the labour force, while also fostering continued support at all stages of children’s development (Gimenez-Nadal, Molina & Ortega, 2012).

However, changes in the women’s roles across different European countries have been uneven. Compared to the 70% of female labour force in the U.S. and northern Europe, only 58% of women in Southern Europe have an opportunity to work (Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2012). State policies adopted by countries in Southern Europe do not favour women’s re-entry into paid labour force.

Women who return to work earlier after childbirth have better opportunities to earn good wages, pursue a prospective career, and provide for their families’ living. In all these situations, government policies aimed to provide sufficient day care opportunities for children and reduce the length of paid parental leave will work as a strong incentive for women to enter paid labour force, while their children are still young.

Women and Choices: Paid Labour, Childbirth, and Theories

Numerous theoretical models were developed to explain the economics of mothers’ early re-entry into paid labour force. All these models universally confirm that women who get back to work while their children are still young benefit themselves and their society. The choices facing women in terms of work and child care can be reviewed in the context of opportunity costs.

In other words, women with young children will have to weigh the relative benefits of being employed against the benefits of staying at home and caring for the child. Basically, when the opportunity costs for paid labour exceeds that of being a mother, more women will prefer work to childbirth (ESHRE Capri Workshop Group, 2010).

The opportunity costs of being employed become higher with women’s higher educational attainment and higher levels of wages (ESHRE Capri Workshop Group, 2010). This relationship between the benefits and costs of labour and childrearing also implies the fundamental role of government policies, which can manage these costs.

The direction of such policies will usually depend on the long-term goals set by governments. Apparently, in the countries where fertility levels are low, governments will seek to increase the costs of employment against the costs of being a mother, and vice versa. For instance, increased maternity benefits and paid parental leaves will reduce the costs of motherhood against the rising costs of continued employment.

Still, being a working mother with a young child is a much better option that staying at home. A mother’s decision to keep away from work for the sake of childrearing can have far-reaching implications for her career and participation in labour force. Mothers who exit paid labour force to care for their children fail to accumulate enough work-related skills and talents capital (Drange & Rege, 2012).

Simply stated, the skills and knowledge of mothers, who do not work, tends to depreciate. More importantly, labour market opportunities usually depend on the quality and complexity of the connections and networks developed by workers in the pursuit of a prospective career (Drange & Rege, 2012).

In addition, being away from work for a lengthy period of time can be devastating for the economic wellbeing of the mother and society at large. At the individual level, and in long-term periods, mothers who do not work and stay with their children at home will have lower lifetime earnings and reduced pension disbursements (Ronsen & Kitterod, 2012).

At the level of society, lengthy parental leaves lead to the reductions in female labour supply, which cannot benefit the developed world with its ageing population and the growing demand for quality labour (Ronsen & Kitterod, 2012). Again, these theoretical assumptions confirm that government policies, which are too family-friendly, will not benefit the working society.

Women should get back to work, when their children are young, while the government must provide the resources and assistance needed to motivate women to work and fulfil their family responsibilities.

Apart from the opportunity costs of employment and child care, women’s choices are influenced by the following factors: industry characteristics, demographic and human capital features, and health characteristics. Women who used to work in industries with better job creation opportunities are less likely to quit their jobs after they give birth to a child (Hotchkiss, Melinda & Beth, 2011).

Women who earned higher wages and did not change their jobs one year preceding their pregnancy are less likely to exit labour force after childbirth (Hotchkiss et al., 2011). The opportunity costs of leaving the job for such women are much higher than those of staying at home.

This is why women who take low-skilled jobs or tend to change their jobs frequently will be more likely to exit labour force, because the costs of this decision are lower than the costs of staying in the workforce.

At the same time, if the infant is born premature or has considerable health problems, women will leave their jobs regardless of the educational, social, and workforce characteristics mentioned above (Hotchkiss et al., 2011). This is why governments should deliver advanced support to mothers with young children, if they seek to increase women’s participation in labour force.

Government Policies: Impacts and International Comparisons

Government policies play a fundamental role in motivating and supporting women with young children, who want to work. The results of the most recent studies imply that such policies may have differential impacts on women’s willingness to work, but policies that emphasise family-friendly approaches will be absolutely counterproductive (Ronsen & Kitterod, 2012).

This is exactly what happened in Norway, where the welfare government implemented generous family-friendly approaches that fostered gender gaps in wages and discouraged women from entering paid labour force (Ronsen & Kitterod, 2012).

Since recently, the country has implemented several policy options to increase women’s education and change society’s expectations that would praise women for their early return to work. In addition, Norway has made a huge leap forward to satisfy the growing demand for publicly subsidised day care (Ronsen & Kitterod, 2012).

Actually, providing subsidised day care has become an essential driver of increased women’s participation in paid labour force across all Scandinavian countries (Drange & Rege, 2012). By contrast, in Spain, where day care services are still inadequate and rigid in terms of working hours, women are mostly discouraged from being employed, while their children are still young (Gimenez-Nadal et al., 2012).

The length of parental leave also plays a role in how women make choices regarding employment. In Austria, the reductions in parental leave duration in 1996 led to the subsequent increase in the number of working women (Lalive & Zweimuller, 2005). The same patterns were observed in Germany, where parents receive benefits for not being at work after childbirth for only 12 months (Bergemann & Riphann, 2011).

Paid leaves are less motivating to parents with children (Rossin-Slater, Ruhm & Waldfogel, 2013). In the United Kingdom, wages play one of the most salient roles in driving women’s participation in paid labour (Kalenkoski, Ribar & Stratton, 2009).

Theoretically, government reforms enhance women’s participation in labour force (Bergemann & Riphann, 2011). Government policies should provide publicly subsidised and universally accessible day care, increase women’s earnings and education levels, as well as reduce the amount and length of benefits paid to mothers and fathers after childbirth.

In this context, women will be better motivated to enter paid labour force, thus benefiting their own wellbeing and the wellbeing and growth of their society. Women should enter paid labour force early after childbirth, but only when the government provides adequate support to guarantee children’s normal development and growth.

Conclusion

Women’s decision to work or not to work is based on the opportunity costs of employment and maternity leave. Today, women who return to the labour force while their children are still young experience better wages and career prospects. They also increase the supply of labour force, thus benefiting the society at large. The government plays a fundamental role in developing work incentives for women with small children.

Through subsidized and universally accessible day care, higher wages, and reduced parental leaves, the government can increase the number of women who re-enter paid labour force. At the same time, when fertility rates become too low, the government will try to increase the costs of employment for mothers, by delivering substantial maternity benefits and paid parental leaves.

References

Bergemann, A. & Riphahn, R. (2011). Female labour supply and parental leave benefits – the causal effect of paying higher transfers for a shorter period of time. Applied Economics Letters, 18(1), 17-20.

Drange, N. & Rege, M. (2012). Trapped at home: The effect of mothers’ temporary labor market exits on their subsequent work career. Norway: CESifo.

ESHRE Capri Workshop Group. (2010). Europe the continent with the lowest fertility. Human Reproduction Update, 16(6), 590-602.

Gimenez-Nadal, J.I., Molina, J.A. & Ortega, R. (2012). Self-employed mothers and the work-family conflict. Applied Economics, 44(17), 2133-2147.

Haygne, H.V. & Bianchi, S.M. (1994). Married mothers’ work patterns: The job-family compromise. Monthly Labor Review, 24-30.

Hotchkiss, J.L., Pitts, M. & Walker, M.B. (2011). To work or not to work: The economics of a mother’s dilemma. Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta: Working Paper 2011-2.

Kalenkoski, C.M., Ribar, D.C. & Stratton, L.S. (2009). The influence of wages on parents’ allocations of time to child care and market work in the United Kingdom. Journal of Population Economics, 22(2), 399-419.

Lalive, R. & Zweimuller, J. (2005). Does parental leave affect fertility and return-to-work? Evidence from a “true natural experiment.” Zurich: Institute for the Study of Labour.

Lavery, D. (2012). More mothers of young children in U.S. workforce. Population Reference Bureau. Web.

Ronsen, M. & Kitterod, R.H. (2012). Entry into work following childbirth among mothers in Norway. Recent trends and variation. Discussion Papers No. 702: Statistics Norway.

Rossin-Slater, M., Ruhm, C.J. & Waldfogel, J. (2013). The effects of California’s Paid Family Leave Program on mothers’ leave-taking and subsequent labor market outcomes. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management, 32(2), 224-245.