Abstract

The purpose of this research was to assess the antecedents of virtual team effectiveness. To understand these issues, the study deployed a theoretical framework by reviewing the past and present studies related to the subject matter. Data was collected using questionnaires and was analyzed by statistical tools. Regression and correlation analyses evaluated the relationship between the variables. The model additionally recognized a couple of elements as having more impacts than others have. This justifies the choice of the model. The results revealed that the geographical gap between the virtual team members brings negative consequences to the working environment. It affects the correspondence quality and shared mental models. It also affects the correspondence quality with its impacts on the working environment and shared group mental models. Consequently, the separation of the team members affects the shared mental models with its consequences for correspondence quality and compelling coordination and mediated correspondence with its impacts on correspondence quality and interpersonal atmosphere.

Introduction

Overview

This section explores the context of the research, statement of the problem, research aims, research questions, and the implication of the study.

Background to the study

Current changes in technology together with a quickly changing business setting have made both the capacity and requirement for associations to work over a geographical separation (Kantabutra & Avery 2010). Virtual teams are dedicated colleagues who are physically isolated from each other and depend on data innovations to impact the team communication up, and arrange work to accomplish a typical objective (Gallos 2008; Cramton 2001; Maznevski & Chudoba 2000). They permit businesses to influence the scholarly resources, improve group work execution, the evolving client requests and procure and maintain an upper hand in turbulent and aggressive situations (Malhotra et al. 2001; Kang & Singh 2006). Subsequently, it is normal to see associations depend on virtual groups for center procedures including learning administration, research and development and item advancement, programming improvement, client administration, and strategic examination (Espinosa et al. 2007; Majchrzak et al. 2000; Maznevski & Chudoba 2000).

Such a gap, which is a successive event as fields mature, makes it hard to completely comprehend the working of virtual groups and acquire a coordinated and all-encompassing perspective of the components adding to or hindering virtual group execution (Sole & Edmondson 2002; King & He 2005). The headway of an area of study requires the aggregation and refinement of an assortment of learning and the mix of past studies and discoveries (Malhotra & Majchrzak 2004; King & He 2005). The increase of much knowledge and advantages come through a thorough audit of experimental proof, looking at both the immediate and backhanded drivers of diverse execution measurements in virtual groups. Computer-mediated communications promote the sharing and correspondence of data among colleagues, which would somehow absolutely influence the yield quality and fulfillment with group forms (Piccoli, Powell & Ives 2004; Cramton 2001; Jha 2014).

Statement of the problem – antecedents of virtual team effectiveness

In recent years, there has been a considerable assortment of learning concerning the antecedents of virtual team effectiveness (King & He 2005). This study, therefore, stays divided, with little investigation of the connections and associations among these forerunners of virtual group execution. Further jumbling the comprehension is the way that there is much concentration on diverse measurements of execution, which makes the examination and incorporation of discoveries crosswise over complex studies. To understand this diverse quality, there is a separation of concepts in line with three key scientific classifications. The first classification is the measurements of execution. The second includes configuration, emergent procedures, and developing states. Finally, the third classification includes interpersonal, assignments, and information technology components. This method yields various essential advantages (King & He 2005).

This approach additionally allows for developing procedure and rising state variables to execution and gives both bits of knowledge relating to virtual group execution under further learning. The exact confirmation checked on gives backing to these distinctions, as they contrastingly influence virtual group execution. Past the wide advantages picked up by taking a separated and coordinated perspective of execution, configuration components, rising procedures, and rising states, and interpersonal, errand, and information technology-related elements, separating every measurement yields important experiences.

Research purpose and rationale

Incorporating the existing literature will lead to a better appreciation of key issues that relate to the subject that the case study will reveal. The rationale for conducting this study has arisen from the need to understand the antecedents of the virtual team. Currently, organizations increasingly appreciate human capital as a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Thus, the need to adopt effective ways that help to get the job get done. Such consideration will provide the organization’s management team with an insight on how to adjust their employee effectiveness.

Research objectives

This paper intends to achieve several objectives, which include:

- To evaluate the basis for the implementation of virtual teams, and

- To assess the factors that make the virtual teams effective.

Research question

The above research objectives will be assessed by taking into consideration the following research question.

What are the antecedents of virtual team effectiveness?

Research Hypothesis

To achieve the research objective, the proposal is based on the following null (H0) and alternate (H1) research hypotheses.

- H0: The use of virtual teams has great benefits for an organization.

- H1: The use of virtual teams has no benefits to an organization.

Justifications of the study

This work adds to both research and practice. It allows for the recognition of the key components of virtual group execution and sees how they relate with one another. By separating the measurements of execution between planned and new components, and between procedures and states, while in the meantime analyzing the complex resembling system uniting these unique variables, there is the capacity to arrange and incorporate the virtual groups’ research. This expanded accuracy and acknowledgment of interrelationships is especially essential in situations where there have been contentions with conflicting discoveries.

Furthermore, the acknowledgment of hypothetical and methodological similitudes within, and contrasts over classes further helps the researchers and scientists to better outline (both hypothetically and methodologically) the studies in the future. The fourth point is that this work emphasizes the significance of perceiving the interconnections among constructs and fortifies the prevalence and significance of intervention and control parts of rising group procedures. It also states and clarifies the contrasts and the interrelationships among distinctive sorts of virtual group execution. This procedure produces results that permit managers of virtual groups to organize their activities and choices to concentrate on the results that are essential to them.

This framework likewise furnishes managers with a model of virtual group execution. This can assist them with making the complex connections and reliance among those variables set toward the formation of the group (much of the time outside their control) and those that emerge over the life of the group (in which they might assume more impact).

Conclusion

In line with examination on virtual group efficiency, the proof concentrates vigorously on the indications of yield quality. Aside from the negative impacts of requesting assignments and intervened correspondence, there is an astounding absence of confirmation for antecedents of yield amount. This attention on virtual group efficiency from numerous points of view reflects comparable patterns in the customary group writing, which likewise at first centered on profitability. This center is certainly not shocking, given that efficiency is the clearest administrative metric for evaluating the achievement or disappointment of a group (Jha 2014).

Literature Review

Introduction

This section surveys the hypotheses both exact and hypothetical that is nearly connected with the antecedents of virtual team effectiveness. Various works of literature that are related to the subject matter have been explored to shed light on the same.

Standing in line with previous studies

Analysis of virtual groups is still in its incipient stages and view of the relative originality of virtual groups; there are numerous ranges of exploration yet to emerge (Badrinarayanan & Arnett 2008; Prasad & Akhilesh 2002). Setting up a framework for a virtual group still requires a huge building exertion, which speaks to a noteworthy deterrent for the implantation of this new worldview (Camarinha-Matos & Afsarmanesh 2003). Many researchers are of late exploring the antecedents of virtual team effectiveness. A large number of these audits do indeed cover in with this survey regarding the studies they incorporate.

Powerful and effective collaboration crosswise over controls and disseminated groups gets to be vital for the achievement of designing activities (Zhang, Gregory & Shi 2008). In this way, the tests propose that future research should investigate the approaches to improve the execution of virtual groups (El-Tayeh, Gil & Freeman 2008). Nevertheless, none has developed as a solitary, generally acknowledged review of the present comprehension of virtual groups (Badrinarayanan & Arnett 2008; Prasad & Akhilesh 2002). With the quick advancement of electronic data and correspondence media in the most recent decades, disseminated work has turned out to be much simpler, speedier, and more productive (Hertel, Geister & Konradt 2005). Organizations are at present confronting essential and uncommon difficulties in an ever dynamic, continually changing, and complex environment (Rezgui 2007; Adetule 2011). Some researchers endorse the monetary and technological gap between third world countries and first world countries. They explain this by examining the gaps in the levels of delicate technology and delicate environment between the two arrangements of nations (Zhouying 2005). Therefore, this matter deserves consideration.

The rapid advancement of new communication channels, for example, the web has quickened this pattern so that today, a large portion of the bigger association utilizes virtual groups to some degree (Hertel, Geister & Konradt 2005). Data innovation is giving the base important to bolster the improvement of new association shapes. Virtual groups speak to one such authoritative structure, one that could reform the work environment and furnish associations with an uncommon level of adaptability and responsiveness (Piccoli, Powell & Ives 2004). Countering the expanding decentralization and globalization of work procedures, many organizations have responded to their dynamic surroundings by presenting virtual groups that team up by correspondence innovations crosswise over topographical, transient, social, and authoritative limits to accomplish the regular objective in their associations’ yields. Virtual groups are developing in prominence (Aquinas 2006).

Separating among the classifications of concepts of virtual teams emphasizes the most extensive examples of inter-class flow and connections and permits the addition to a general model of virtual group execution (Badrinarayanan & Arnett 2008; Prasad & Akhilesh 2002). Group outline gives the beginning group setting that shapes the future bearing of groups and permits, encourages, compels, or keeps the ensuing development of procedures and states. Group outline variables can influence group execution specifically and by implication, because they encourage, animate, or impede the rise of a few procedures and states. This separation additionally permits the investigation of the connections between emergent elements. Take, for instance, the connections between developing procedures and states, which impact each other, now and then fortifying or changing existing states or forms and at different times making new ones (Badrinarayanan & Arnett 2008; Prasad & Akhilesh 2002).

Various methodologies exist for looking at discoveries over numerous studies, extending along a continuum of expanding evaluation, from account surveys to genuine factual meta-investigation (Clawson 2011; King & He 2005). Expanding evaluation diminishes subjectivity. The greater part of former surveys on virtual groups has been descriptive and overall vulnerable against subjective inclinations (Clawson 2011). Developing procedures, through individuals’ rehashed activities, add to facilitating the formation of emergent states, upkeep, and change. The emergent states consequently, influence emergent procedures by dictating the group choice and structuration of procedures. The system additionally highlights the recursive correlation between yields and group attributes. Having such a summed up model, thus, permits for a better arrangement for future examination and arranging its discoveries inside of the collection of surviving learning (King & He 2005).

Out of the five variables, four are engaging – giving some more objectivity, yet at the same time missing the mark concerning that given by either vote-numbering or genuine meta-examinations (Clawson 2011; King & He 2005). This recommends a requirement for a target audit of virtual groups’ exploration that lays on an arrangement of precise methodology for organizing the observational confirmation. Taken together, there is a requirement for a target and comprehensive audit of writing on virtual group elements and execution to serve as a premise for incorporating the present comprehension on the theme.

Antecedents of virtual team effectiveness

Virtual groups’ components are in three unique classes. The first is design elements (for example, geographical scattering, IT elements, and framework, or the way of the assignment). The second is emergent group forms (for example, overseeing clashes, applying particular styles of administration, utilizing PC intervened correspondence, or depending on formal behavioral control systems). The third class is emergent group states (Ilgen et al. 2005; Marks, Mathieu & Zaccaro 2001). In virtual groups, every classification encompasses three sub-classifications, for instance, task, information innovations, and interpersonal. The task is the other name for activity procedures (Kirkman et al. 2004; Marks, Mathieu & Zaccaro 2001). Group configuration elements can influence diverse sorts of execution positively and/or negatively, through rising group procedures and states (Clawson 2011; King & He 2005).

Likewise, virtual teams work in different geographical locations with the common aim of achieving the group’s objectives. While various earlier surveys have been directed on the antecedents of virtual teams, numerous have picked to limit their degree to specific variables (Bannan-Ritland 2002; Dennis, Wixom & Vandenberg 2001; Nash et al. 2000). Others have limited the area inside which they contemplated virtual group motion (Bannan-Ritland 2002). Virtual groups are imperative systems for associations trying to influence rare assets across geographic and different limits (Munkvold & Zigurs 2007; Anderson et al. 2007). Capacities of this sort offer associations a type of upper hand (Bergiel, Bergiel & Balsmeier 2008). Virtual groups speak to an extensive pool of new item knowledge, which is by all accounts a promising wellspring of advancement (Fuller et al. 2006).

Keeping in mind the end goal to give a premise to understanding the vast assemblage of examination on virtual group adequacy, a given survey must evaluate the full arrangement of pertinent exploration. This is especially troublesome for the examination of virtual groups given that virtual groups are intricate frameworks influenced by wide-ranging elements including innovation, social elements, and social structure. An outcome of this constraint is the different combinations performed in these surveys that stay hard to coordinate. This recommends a requirement for a coordinated audit that explores the surviving information overall spaces and addresses all parts of such groups (Clawson 2011; King & He 2005).

Virtual groups effectiveness

The scaling of technological advances has necessitated the application of virtual groups (Beranek & Martz 2005). Authoritative and social hindrances are also a genuine obstruction to the adequacy of virtual groups (Gallos 2008). As a drawback, virtual groups sometimes experience communication breakdowns, and conflicts of control as the individuals work apart (May & Carter 2001; Rosen, Furst & Blackburn 2007). The display time is a standout amongst the most imperative solutions for achievement in assembling organizations (Sorli et al. 2006; Qureshi & Vogel 2001).

Various researchers have alluded that the significance of reviewing group execution encompasses three unmistakable measurements. These elements are profitability (Bass 2005), suitability (Collins 2001), and self-improvement (Kouzes & Posner 2012; Daft 2005). The separation among these measurements allows for the understanding of the unmistakable cooperation and interdependencies that exist among diverse predecessors of a particular measurement of execution. This creates a more nuanced and exact comprehension of virtual group execution drivers. The principal, profitability is the degree to which a group’s yield meets or surpasses the models of those getting it and incorporates measures like amount, proficiency, yield quality, auspiciousness, and imagination (Clawson 2011; King & He 2005). The second, reasonability, is the degree to which completing its work allows or upgrades a group’s capacity to keep cooperating and incorporates components like fulfillment and ability to cooperate later on. Finally, self-awareness is the degree to which a group’s experience satisfies the individual needs, builds to the development and individual prosperity of its individuals, and incorporates elements like learning.

Constructing and working in virtual groups is valuable for ventures that need practical ideas and the way to their quality construction is to ensure a branded approach to defeat the concerns emphasized, particularly the time differences and social matters (Clawson 2011; King & He 2005). While correspondence is a conventional group issue, factors like geographic separation, social differing qualities, and dialect or accent challenges amplify it (Sole & Edmondson 2002). For promotions or comparative big ventures, individual task administration competency, fitting utilization of innovation and systems administration capacity, eagerness for self-administration, social and interpersonal mindfulness is essentials of an effective virtual group (Lee-Kelley & Sankey 2008). The innovation facilitator part could be fundamentally vital to virtual group achievement (Thomas & Bostrom 2005).

A thorough survey is relevant to identifying connections among pertinent forerunners of particular measurements of execution that exist in the current literature (Majchrzak et al. 2000). For instance, while interesting mastery and imparted comprehension directly correlate to result from quality and advancement, the relationship between these indicators stays indistinct (Balthazard, Potter & Warren 2004; Yoo & Kanawattanachai 2001). Consequently, the objective of this paper is to survey and combine the present writing keeping in mind the end goal to create resembling nets that guide the variables driving virtual group execution (Malhotra & Majchrzak 2004). The paper is a push to give a complete point of view of the connections among components of virtual groups, to add to a superior comprehension of how they positively and negatively influence execution, and to provide substantive bearings for future examination.

Features of team design

Group configuration influences three parts of the group, for instance, information technology, interpersonal, and assignment or task (Annabelle 2006; Flint 2012). Interpersonal elements (additionally alluded to as enrolment components) are the qualities of individual colleagues and the subsequent group-level auxiliary properties molded by those people characteristics. Group outline gives the starting venture arrangement, setting the stage for the group to start to work, and giving the basic connection inside which the group develops (Clawson 2011; King & He 2005). It provides the situational advantages and requirements that influence the event and significance of virtual collaboration (Johns 2006). They incorporate identity qualities (Balthazard, Potter & Warren 2004), aptitude (Malhotra et al. 2001), a scattering of physical location (Hinds & Bailey 2003), group size (Majchrzak, Malhotra & John 2005), and different properties of the group specifically identified with its participation.

Assignment or task variables allude to both the nature and qualities of the undertaking in progress. Illustrations incorporate the required level of reliance, many-sided quality, new item advancement, or research and advancement (Hinds & Mortensen 2005; Malhotra et al. 2001). Information technology components incorporate the sorts of data advancements used to bolster virtual group cooperative procedures, for example, PC conferencing frameworks (Avolio, Walumbwa & Weber 2009), e-mails (Mortensen & Hinds 2001), and sound/videoconference frameworks (Andres 2002). The procedures catch how individuals act, carry out their employment, interface with different individuals, and utilize information technology.

In the domain of activities, group procedures are powerful and commonly transient. As colleagues collaborate and take part in continuous exercises, new developing procedures arise and existing ones are strengthened and/or rapidly change (Johns 2006; Marks, Mathieu & Zaccaro 2001). Similarly, as with outline elements, there are three sorts of rising group forms, for instance, interpersonal, assignment, and information technology. Interpersonal procedures are the exercises performed by individuals from virtual groups to oversee connections among them (Marks, Mathieu & Zaccaro 2001). They incorporate procedures for overseeing strife (Montoya-Weiss, Massey & Song 2001), building trust (Hughes, Ginnett & Curphy 2012; Walther & Bunz 2005), and another intellectual, verbal, and character exercises used to oversee socio-enthusiastic and full of feeling progress inside of the group (Kayworth & Leidner 2000).

Assignment procedures are the exercises performed by individuals from virtual groups to structure, sort out, control, and screen work inside virtual groups. They incorporate trading assignment-related data and learning (Majchrzak et al. 2000; Maznevski & Chudoba 2000), depending on organized procedures (Kirkman, Gibson & Shapiro 2001), and taking advantage of the virtual team partners (Huang et al. 2002; Massey, Montoya-Weiss & Hung 2003). Information technology rising procedures are the psychological, verbal, and behavioral exercises identified with information technology use and capacities. These incorporate utilizing PC intervened correspondence (Maznevski & Chudoba 2000; Robey & Khoo 2000; Yoo & Kanawattanachai 2001) and adjusting information technology to the setting of the group (Montoya-Weiss & Hung 2003; Majchrzak et al. 2000). Altogether, the three sorts of new procedures catch individuals’ activities aimed at changing over inputs into yields.

Foundation and developments of virtual teams

Virtual teams started in the year 1960 in the US. In the late 1980s and mid-1990s, numerous organizations executed self-overseeing or enabled workgroups. To cut administration, lessen process duration, and enhance service quality, line-level workers assumed decision-making and critical thinking obligations generally meant for the senior management (Piccoli & Ives 2003; Kirkman, Gibson & Shapiro 2001). Presently, because of the innovation in communication equipment and widespread globalization, virtual groups have expanded quickly around the world (Kirkman et al. 2002; Walvoord et al. 2008, Avery 2004).

However, it is critical to perceive that lack of examination on virtual group learning and feasibility or the researchers’ capacity to estimate, and specialists’ capacity to oversee are restricted. For both researchers and professionals, a model of virtual groups that concentrates exclusively on yield may not catch huge numbers of the variables that propel individual colleagues like fulfillment or self-awareness. It additionally dangers concentrating on fleeting increases (as more or better yield) at the expense of long-run advantages as far as solidness or the advancement of individuals as future assets. Consequently, future exploration in the areas of virtual group advancement and practicality is required.

Virtual groups have additionally been the subject of significant research consideration, which has yielded knowledge on the drivers of distinctive measurements of execution. In any case, the insight on the theme, particularly how drivers identify with each other, stays divided rather than coordinated. For example, analysts have explored the impact of the components like trust (Kanawattanachai & Yoo 2002; Paul & McDaniel 2004). Others have explored the component of clashes (Mortensen & Hinds 2001; Keller 2006) and shared standards of use of information technology (Malhotra & Majchrzak 2004). In the same way, there are explorations on assigning information technology to tasks and on the nature of the yield of virtual groups (Ferch & Spears 2011). Others have considered the impacts of shared comprehension (Malhotra et al. 2001), and geographical scattering on inventiveness and development (Gibson & Gibbs 2006).

Exploration has likewise been directed to comprehend the impact of computer-mediated communications (Andres 2002; Blanchard & Cathy 2002) on the creation effectiveness of virtual groups. The components affecting part fulfillment, for example, administration style (Kayworth & Leidner 2000), sharing and conveying data (Jarvenpaa, Shaw & Staples 2004; Piccoli, Powell & Ives 2004) have additionally been examined as has been the impact of fitting information technology on individual learning (Majchrzak, Malhotra & John 2005; Malhotra et al. 2001). Researchers have explored the components incorporated with groups through their beginning outline and those that rise after a while through regular working and connection. They have analyzed the qualities of virtual groups’ participation, their assignments, and their advances.

Applicability of virtual team

The idea of a “team” is a little number of individuals with integral attitudes who focus on a typical reason, objectives, or working methodology for which they consider themselves commonly responsible (Zenun, Loureiro, & Araujo 2007). It is worth specifying that virtual groups shape to overcome vast geographical segregations (Cascio & Shurygailo 2003). Writing identified with virtual groups uncovered an absence of profundity in the definitions. Albeit virtual cooperation is a present point in the literature on worldwide organizations, it has not been easy to characterize what “virtual” means over numerous institutional settings (Chudoba et al. 2005). Virtual groups, therefore, are gatherings of people teaming up in the execution of a particular undertaking while at the same time are geographically distributed, potentially any place inside their main association (Leenders, Engelen & Kratzer 2003). Virtual groups can be gatherings of individuals who cooperate even though they are regularly scattered crosswise over space, time, and/or hierarchical limits (Lurey & Raisinghani 2001).

The virtual group is a gathering of individuals and sub-groups who connect through related undertakings guided by normal reason and work crosswise over connections fortified by data, correspondence, and transport innovations (Gassmann & Von Zedtwitz 2003b). Another definition proposes that virtual groups are convened workgroups whose individuals are geographically scattered and organize their work dominatingly with electronic data and correspondence technologies (Hertel, Geister & Konradt 2005). Virtual groups work crosswise over limits of time and space by using advanced PC driven advances. The expression “virtual group” normally includes an extensive variety of exercises and workings that rely on innovation (Anderson et al. 2007). Virtual groups include individuals who station in various physical areas. This group characteristic has cultivated broad utilization of an assortment of types of PC intervened correspondence that empowers geographically scattered individuals to organize their endeavors and inputs (Peters & Manz 2007).

Amongst the diverse meanings of the idea of a virtual group the one that stands out is virtual groups are gatherings of geographically, hierarchically, and/or time scattered workforce united by data innovations to achieve one or more association’s undertakings. This procedure gives a more exact comprehension of the synergistic, integral, and in some cases restricting impacts of diverse sorts of components on distinctive parts of execution that could conceivably be corresponding. Secondly, gathering individual builds into classifications of outline variables, emergent procedures, and states. The varying measurements of execution permit for the recognition of more extensive examples of inter-category elements and connections; the acknowledgment of which allows for the accurate credit impacts to either individual elements or the more extensive classes to which they have a place.

Structures of virtual teams

For the most part, there are different types of “virtual” labor contingent upon all the individuals included and the level of connection that they have. The principal is “telecommuting” (working from home). Telecommuting occurs in part or totally outside of the principal organization’s working environment with the guide of data and telecom services. There is evidence of “virtual teams” when a few telecommuters are all under the same boss. Interestingly, the virtual group is portrayed in a scenario when individuals meet the basic objectives of the company by getting the job done as a group. At last, “virtual groups” are bigger elements of appropriated work in which individuals participate using the web, guided by basic purposes, parts, and standards. Virtual societies are not tangible within the frameworks of a company, nevertheless somewhat introduced through a few of the participants in the company. Illustrations of virtual groups are Open Source programming activities (Hertel, Geister & Konradt 2005).

Teleworking provides an option to composting efforts like that includes a thorough or fractional utilization of ICT to empower specialists to become accustomed to their activities from diverse and remote areas (Martinez-Sanchez et al. 2006). Telecommuting gives cost-saving funds to workers by disposing of tedious drives to central workplaces and grants the team’s additional adaptability to streamline their career and family obligations (Johnson, Heimann & O’Neill 2001). Some researchers have illuminated the diverse types of the virtual group by ordering it regarding two essential variables, in particular, the quantity of area (one or more) and the number of directors (one or more) (Cascio & Shurygailo 2003). The kinds of virtual teams exist in four ways. The first kind is teleworkers, which has only one manager who is located at one location and managing a team. The second one is the remote team in which one manager is in charge of a team that is located in multiple areas (Martinez-Sanchez et al. 2006).

CMC (Computer-Mediated Collaborations) is important for enveloping offbeat cooperation over a collective working environment, and also email, texting, and synchronous collaborations utilizing a framework that joins common workstations, desktop video conferencing chats, and different elements (Rice et al. 2007; Sorli et al. 2006). Communitarian networked associations are bodies in which their legitimate comprehension, outline, usage, and administration require the reconciliation of diverse demonstrating points of view (Camarinha-Matos & Afsarmanesh 2007).

Utilizing virtual teams

The weight of globalization makes the rival organization’s faces expanded weights to fabricate minimum amount, stretch to fresh arcades, and bridge expertise gaps. The new item improvement endeavors are progressively important for numerous countries over all types of structures of an organization (Cummings & Teng 2003). Given the subsequent contrasts in time differences and geographical separations in such endeavors, practical new product development tasks are accepting expanding consideration (McDonough, Kahn & Barczak 2001). The utilization of virtual groups for new item advancement is quickly developing and associations can be is one answer for small and medium ventures (SMEs) having the vision to build their intensity (Kline 2010). The mix of touchy learning development and cheap data exchange makes a prolific ground for a boundless invention of virtual teams (Miles, Snow & Miles 2000).

Pros and cons of virtual teams

Amid the most recent decade, words, for example, “virtual”, “virtualization”, “virtualized” have been all the time upheld by researchers and experts in the examination of collective and monetary matters (Vaccaro, Veloso & Brusoni 2008), however, the points of interest and drawbacks of the virtual group cannot be outlined. Finding the adaptable and designable benchmark is among the main points of interest of light-footed virtual groups. Anderson et al. (2007) recommend that the compelling utilization of correspondence, particularly amid the early phases of the group’s improvement plays a just as essential part of picking up and looking after trust. Virtual research and development groups in which individuals work in different times or places regularly confront tight calendars with a requirement to begin rapidly and implement quickly (Munkvold & Zigurs, 2007; Stoker et al. 2001; Gassmann & Von Zedtwitz 2003a).

Dissimilar to a customary group, a virtual group works crosswise over space, time, and authoritative limits with connections fortified by networks of correspondence advancements. Nevertheless, a hefty portion of the best practices for conventional groups is like those for virtual groups (Bergiel, Bergiel & Balsmeier 2008). Virtual groups are altogether not the same as customary groups. In the typical conventional group, the individuals work by each other, while in virtual groups they work in distinctive areas. In conventional groups the coordination of undertakings is clear and performed by the individuals from the group together; in virtual groups, in contrast, errands must be a great deal all the more exceedingly organized. Additionally, virtual groups depend on electronic correspondence, rather than eye-to-eye correspondence in customary teams (Kratzer, Leenders & Engelen 2005). Specifically, dependence on PC interceded correspondence makes virtual groups one of a kind from conventional ones (Munkvold & Zigurs, 2007). Customary innovative workgroups have gotten to be uncommon.

The procedures utilized by fruitful virtual groups will be not the same as those utilized as a part of eye-to-eye coordinated efforts (Rice et al. 2007). In a development system taking after a “customary” association, the advancement procedure faces the limitation by area and time. At the end of the day, the advancement handle, for the most part, happens inside of the structure of physical workplaces and working hours. In virtual associations, people’s work does not have limitations of time and place, and correspondence is emphatically encouraged by information technology. Such an item improvement environment permits a more noteworthy level of opportunity to people included with the advancement venture (Ojasalo 2008). Thus, multinational organizations will probably turn out to be part of a worldwide research and development system than littler unit (Boehe 2007). Dispersed groups can do basic undertakings with proper choice bolster advances.

An essential lesson is that the web assists organizations with being both worldwide and local simultaneously. It is conceivable to infer that the virtual groups substitute with the web. The web can encourage the coordinated effort of diverse individuals who are included in item advancement, build the velocity and the nature of new item testing and acceptance and enhance the viability and the proficiency of item improvement and dispatch (Lurey & Raisinghani 2001). Geographical measurement is not a variable that affects considerably the typology and destinations of research and development participation. This conforms with the outcomes highlighted in the writing survey that they have done. Virtual groups have more powerful research and development continuation choices than face-to-face groups because the virtual group has offbeat correspondence and it takes into account more opportunity for assimilation and lessens the weight of team similarity (Cummings & Teng 2003).

Probably, virtual groups will not supplant customary groups. Albeit virtual groups are and will keep on being a critical and important sort of work game plan, they are not proper for all circumstances. Some researchers rely on virtual groups overview in 12 separate virtual groups from eight distinctive donor organizations in the high innovation found that associations deciding to actualize virtual groups ought to concentrate quite a bit of their endeavors in the same bearing they would on the off chance that they were executing conventional, co-found groups (Lurey & Raisinghani 2001). Technology empowered virtual cooperation is successful with the presence of face-to-face correspondence. It can bolster and prompt larger amounts of fulfillment in a coordinated effort. Assorted qualities in the national foundation and society are basic in transnational and virtual groups. Past exploration has found that collaboration in PC interceded correspondence settings is more generic, more undertaking focused, more systematic, and less well-disposed than in up close and personal settings. The utilization of information and communication technology affected the information base group’s execution.

Challenges of virtual teams

Virtual groups have specific difficulties including trust (Malhotra, Majchrzak & Rosen 2007). Trust is a key component to construct fruitful associations and to overcome narrow-minded interests, powerful correspondence that is much more basic for achievement in the virtual setting, due dates, and group togetherness. While incredibly favorable circumstances accompany the selection of the virtual groups, new difficulties ascend with them. There are five principle burdens to a virtual group: the absence of physical connection, loss of up close and personal cooperative energies, the absence of trust, more prominent worry with consistency and dependability, and absence of social communication (Cascio 2000; Lurey & Raisinghani 2001). In building a virtual group, these issues must be at any rate verifiably tended to with a specific end goal to have a compelling virtual group. Virtual groups are tested because they are virtual; they exist through PC intervened correspondence innovation instead of eye-to-eye cooperation.

Now and again, the answer to diverse managers and they work as engaged experts who utilize their drive and assets to add to the achievement of the group objective. Less open door for casual work and non-business related discussions may frame difficulties to the virtual group. Besides, the virtual group’s members are relied upon to end up related and completely negotiate social contracts, and perform their errands through PC-mediated innovation. The procedure to inspire colleagues may vary contingent upon their introduction (Lurey & Raisinghani 2001).

Conclusion

Incorporating the existing literature will lead to a better appreciation of key issues that relate to the subject that the case study will reveal. The rationale for conducting this study has arisen from the need to understand the antecedents of the virtual team. Currently, organizations increasingly appreciate human capital as a source of sustainable competitive advantage. Thus, the need to adopt effective ways that help to get the job get done. Such consideration will provide the organization’s management team with an insight on how to adjust their employee effectiveness. This paper intended to achieve several objectives, which include:

- To evaluate the basis for the implementation of virtual teams, and

- To assess the factors that make the virtual teams effective.

A survey of the available literature demonstrates that the elements that influence the adequacy of virtual groups are still uncertain. A hefty portion of the recognized difficulties of a powerful virtual group working aims on guaranteeing great correspondence among all individuals from the group (Anderson et al. 2007). For instance, some researchers found that customary and auspicious openness input was of the utmost importance to building trust and duty in appropriated groups. Social dimensional components should start at an early stage in the virtual group formation process and are basic to the adequacy of the group. Correspondence is an apparatus that specifically affects the shared measurements that form the group (Clawson 2011; King & He 2005).

Further to the execution of the group, it has a direct effect on the fulfillment with the virtual group. In the case of groups moving to virtual situations, it takes a longer period to adjust because the procedure is accompanied by experimentation situations. This procedure is important to support powerful virtual groups. Notwithstanding powerless ties between virtual colleagues, guaranteeing parallel correspondence is perhaps sufficient for compelling virtual group execution (Lurey & Raisinghani 2001). Making a condition of common perception in regards to the objectives and targets, job responsibilities and sharing, the assigned tasks and obligations, and the skills of the partners had a beneficial outcome on yield quality. As criteria, it was necessary to gather the viability appraisals from the group supervisors. The aftereffects of the survey indicated great dependability of the undertaking business-related properties, collaboration related qualities, and ascribes identified with tele-cooperative work (Clawson 2011; King & He 2005).

Methodology

Introduction

Research Methodology is an approach to discover the aftereffect of a given issue on a particular matter or issue that likewise alludes to a problem in research. In Methodology, analyst utilizes diverse methods for comprehending and looking at the given problem in research. Diverse sources use a distinctive sort of strategies for taking care of the issue. Considering the term ‘methodology’, provides the method for seeking or taking care of the problem in research. Noting unanswered inquiries or investigating which, as of now, does not exist, is considered to research. A research methodology is a cautious examination or requests particularly through the quest for new realities in any branch of learning (Blanchard & Cathy 2002).

Research philosophy

Research philosophy refers to the development of the research foundation, research information, and its inclination. It is additionally characterized by the use of a research paradigm. The research paradigm is the wide structure, which contains discernment, convictions, and comprehension of a few hypotheses and practices that are utilized to lead research. It is described as an exact methodology, which includes different strides through which an analyst makes a relationship between the research targets and inquiries. Paradigm is a particular state of mind about directing an exploration. It is not entirely a procedure, but rather all the more a logic that aids how the exploration is to be led (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009). Research philosophy and logic contains different variables, for example, the state of mind of an individual, his point of view, the assortment of convictions towards reality, and so on. This idea impacts the convictions and estimation of the scientists, with the goal that he can give substantial contentions and phrasing to give solid results. There are three sorts of research paradigm. They incorporate authenticity, positivism, and interpretivism.

Positivism

This idea is specifically connected with objectivism. With this philosophical methodology, researchers give their perspective to assess the social world with the offer of objectivity set up of subjectivity. This implies the analysts are intrigued to gather general data and information from a substantial social example as opposed to assessing subtle elements of the examination. As indicated by this position, the analyst’s particular convictions have no worth to impact the exploration study. The positivist philosophical methodology is for the most part connected with the perceptions and analyses to gather numeric information (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009).

Interpretivism

This can allude to social constructionism when focusing on research management. As per this philosophical methodology, examination offer significance to their convictions and worth to give a satisfactory defense for a problem in research (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009). With the assistance of interpretivism, scientists center to emphasize the genuine statistical data points as indicated by the problem in research. Interpretivism comprehends particular business circumstances. In this methodology, analysts utilize a sample and assess them in point of interest to comprehend the perspectives of the population.

Authenticity

Realism (or authenticity) predominantly gathers in the truth and convictions in nature. Two primary methodologies are immediate and basic authenticity (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009). Immediate reality implies the tangible attributes that a person can see, touch, or feel. Then again, in basic authenticity, people contend about their encounters for a specific circumstance (Blanchard & Cathy 2002). This is connected with the circumstance of social constructivism because a person tries to demonstrate his convictions and qualities. This study adopted the positivist approach.

Quantitative and Qualitative Approach

Qualitative research, commonly known as subjective research is a form of exploratory examination (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009). It is utilized to pick up a comprehension of hidden reasons, sentiments, and inspirations. It gives knowledge into the issue or creates thoughts or speculations for potential quantitative examination. Subjective research is additionally used to reveal patterns in thought and sentiments and plunge more profoundly into the issue. The subjective information accumulation systems vary utilizing unstructured or semi-organized methods. Some regular routines incorporate focus groups, individual meetings, and cooperation or perceptions. The sample size is ordinarily little, and respondents are chosen to satisfy a given share (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009).

Quantitative research is utilized to evaluate the issue by a method for producing numerical information or data that can be transformed into usable perceptions. It is utilized to evaluate states of mind, suppositions, practices, and smaller results from a bigger sample of the population. Quantitative research utilizes quantifiable information to plan facts and reveal strategies in the analysis. Quantitative information accumulation routines are considerably more organized than qualitative information gathering strategies. Quantitative information gathering techniques incorporate different types of overviews – online studies, paper reviews, phone interviews, longitudinal studies, site interceptors, online surveys, and orderly perceptions.

Merits and demerits of primary research

Primary exploration addresses objective issues. The association requesting the examination has the overall control on the procedure and the exploration is shaped similarly as its destinations and degree are concerned (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009). The organization taking the research can be requested to focus their attempts to discover information concerning a particular market instead of fixation on the mass business sector. The elucidation of information is better in primary exploration. The gathered information can be analyzed and translated by the advertisers relying upon their needs as opposed to depending on the elucidation made by authorities of optional information. Normally auxiliary information is not all that late and it may not be particular to the spot or circumstance that the advertiser is focusing on. Primary research turns into a more precise device since the researcher can utilize the information that is helpful for him. The data collector in primary research is the proprietor of that data and he need not impart it to different organizations and contenders. This gives an advantage over contenders answering optional information (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009).

Gathering information utilizing primary exploration is an expensive affair. Due to the comprehensive nature of the activity, the period needed to do research precisely is long when contrasted with secondary information, which can be gathered in much lesser time length. If the exploration includes taking feedback, there are high risks that the input given is not right. Criticisms by their essential nature are normally one-sided or given only for it. Apart from cost and time, different assets like HR and materials too are required in a bigger amount to do studies and information accumulation (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009).

Research Design

The research design is the output of a progression of choices of the researcher in regards to how the study will be directed. The research design is nearly connected with the system of the study and aides making arrangements for executing the study (Blanchard & Cathy 2002). It is an outline for directing the study that emphasizes control over variables that could meddle with the legitimacy of the discoveries. The research designs differ as to the amount of structure the analyst forces on the examination circumstance and the amount of adaptability is permitted once the study is ongoing. Many quantitative studies have more structured research designs than qualitative studies, which have more fluid research designs.

A strategy that is regularly utilized to acquire data on social and behavioral elements and the connections between these elements is a research survey. In this case, the specialist chooses a specimen or subgroup of individuals and gets some information about issues identified with the examination. The responses to these inquiries are then viewed as a depiction distinguishing the suppositions and states of mind of the entire populace from which the example was taken (Blanchard & Cathy 2002).

Descriptive exploratory design

Many studies of a survey can adopt a descriptive research design or an exploratory research design. Depiction can be a noteworthy motivation behind both subjective and quantitative explorations. The descriptive research design enables the specialist to acquire data regarding any phenomenon. Exploratory studies give an inside and out investigation of a solitary procedure. On the other hand, the descriptive research design analyses the attributes of a particular populace. Both exploratory research design and descriptive research design start with the problem statement. Exploratory exploration goes for researching the research problem, how it is shown, and alternate components with which it is connected. An exploratory research design is embraced when another zone or theme is being researched (Blanchard & Cathy 2002).

Theoretical framework

The new item improvement efforts are progressively important for numerous countries in various types of hierarchical structures (McDonough, Kahn & Barczak 2001; Cummings & Teng 2003). Due to the differences in location and time zones, virtual new product development tasks are accepting expanding consideration (McDonough, Kahn & Barczak 2001). The utilization of virtual groups for new item advancement is quickly developing and associations can be is one answer for ventures having the vision to build their intensity (McDonough, Kahn & Barczak 2001; Kline 2010).

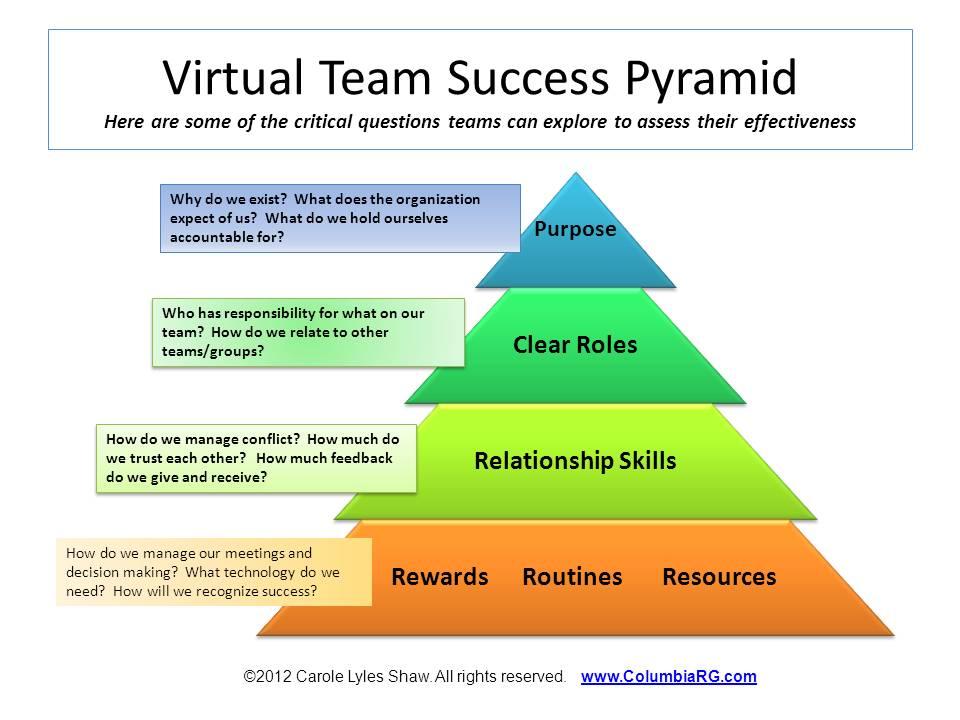

Various methodologies exist for looking at discoveries over numerous studies, extending along a continuum of expanding evaluation, from account surveys to genuine factual meta-investigation (Clawson 2011). Expanding evaluation diminishes subjectivity. To date, the greater part of former surveys on virtual groups has been descriptive and overall vulnerable against subjective inclinations (Clawson 2011). Out of the five variables, four are engaging – giving some more objectivity, yet at the same time missing the mark concerning that given by either vote-numbering or genuine meta-examinations. This recommends a requirement for a target audit of virtual groups’ exploration that lays on an arrangement of precise methodology for organizing the observational confirmation. Taken together, there is a requirement for a target and comprehensive audit of writing on virtual group elements and execution to serve as a premise for incorporating the present comprehension on the theme. Figure 3.1 shows the model used in the research.

Case Study Approach

A contextual (or a case study) analysis includes a very close and point by point analysis of a subject (the case), and also its related logical conditions (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009). Contextual investigations show up with incredible recurrence all through well-known works. Almost anybody with training can make a case for having done a contextual investigation sooner or later in their life. Contextual analyses additionally can be delivered by taking after a formal exploration technique (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009; Blanchard & Cathy 2002).

The subsequent assortment of contextual investigation exploration has long had an unmistakable spot in numerous orders and callings, extending from science, humanities, human science, and political science to training, medical science, social administration, and managerial science. In doing contextual analysis, the ‘case’ being concentrated on may be an individual, association, occasion, or activity, existing in a particular point (Blanchard & Cathy 2002). Case in point, medical science has delivered both understood contextual investigations of people and contextual analyses of medical practices. In any case, when ‘case’ is utilized as a part of a dynamic sense, as in a case, a recommendation, or a contention, such a case can be the subject of numerous exploration routines, not simply contextual analysis research (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009).

One methodology sees the contextual analysis characterized as an examination technique, an exact request that examines a problem inside of its genuine setting. Contextual analysis exploration can mean single and various contextual investigations. It can also incorporate quantitative proof and depends on different sources of confirmation. The methodology advantages from the former advancement of hypothetical suggestions (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009). All things considered, case study investigation ought not to be mistaken for subjective exploration, as contextual investigations can be founded on any blend of quantitative and subjective information (Blanchard & Cathy 2002; Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009). In the meantime, the continuous trials can give a factual structure to making inductions from quantitative information (Blanchard & Cathy 2002).

Population and Sampling

The aggregate gathering of subjects that meet an assigned arrangement of criteria is called a population. There is a refinement between the target populace and the available populace. The target populace incorporates every one of the cases about which the scientist might want to make speculations. The available populace involves every one of the cases that fit in with the assigned criteria and are open to the scientist as available literature. The procedure of selecting a bit of the populace to reflect the whole populace is a sampling (Blanchard & Cathy 2002). Exploratory outline requires little examples that are picked through a deliberative procedure to reflect the wanted populace. In subjective exploration, people are chosen to partake in the examination because of their direct experience of the problem statement (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009). In line with this survey, the population comprised of the employees of the organization under investigation. They were an excellent choice because their profiles fit the setting of this research, and also they had enough experience in the organization.

Not at all like quantitative examination, there is no compelling reason to haphazardly select people, because control and speculation of discoveries are not the expectations of the study (Scott 2011). Purposive inspecting, a technique that includes the choice of persons who speak to the population of interest was, therefore, utilized in this study. This is a non-likelihood testing technique which includes the choice of specific subjects to be incorporated into the. With the end goal of this period of the study, respondents were chosen because they were workers of the association under study. The study had a sum of 203 members.

Even though this methodology expands the likelihood of population samples that do not represent the whole population, it gave the main method for reaching all the respondents (Scott 2011). Since no official registers or records were containing the names of the workers, the specialist chose to utilize snowball testing to distinguish the respondents. Purposive testing and snowball inspecting are connected and have one shared factor: the general population most suitable to interact with on the examination trip are chosen at the time they are required. Snowball testing is important in the subjective examination because it is coordinated at people that are hard to distinguish (Blanchard & Cathy 2002). In snowball testing, the analyst gathers information on a couple of individuals from the objective populace he can find and afterward looks for data from those people that empower him to find different individuals from that populace. These inspecting strategies empower the analyst to choose particular subjects who will give the broadest data about the problem statement being concentrated on (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009).

Data Collection and Instrumentation

The researcher used questionnaires for data collection. A total of 203 questionnaires were completed by the target respondents. The questions were designed in line with the general objective of this study which was to explore the antecedents of virtual team effectiveness. Adopting this method of administration validates the need to minimize the cost of the study. This is because respondents are geographically separated (Blanchard & Cathy 2002; Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009).

Data Analysis and Presentation

The collected data were entered into an excel sheet for coding before further analysis by SPSS. Statistical techniques of analysis were utilized.

Ethical considerations

Just before the study was conducted, the researcher first developed a proposal and submitted it for approval. The proposal entailed the overview and the aims of the study. Besides, the proposal entailed how the respondents of the research would be recruited and handled. The responses of the participants were treated with confidentiality to respect and uphold the welfare and the right to privacy of the participants. Once the approval was given, the researcher went ahead to research while adhering to the stipulated guidelines.

In this exploration, the researcher is speculated to have considered all parts of the ethical issues. The moral issues should be brought up in the proposition of the examination. The research ought to be composed and embraced in a manner that encourages quality and trustworthiness. The study staff should be educated on the reason, systems, and the utilization of the exploration. Moreover, they should look into the needs to regard the secret data and the obscurity of the respondents. The harm that may be transferred to the participants must be avoided. Concerning this study, the information gathered had to be confidential and not reported to others. The members were obliged to partake in the examination wilfully, and they had the privilege of not answering questions that they viewed as uncomfortable. The researcher needed to regard the secrecy of the respondents.

Conclusion

The validity of the data represents the data integrity and it connotes that the data is accurate and consistent. Validity has been explained as a descriptive evaluation of the association between actions and interpretations and empirical evidence deduced from the data. More precaution was taken especially when a comparison was made between the consumers’ commitment and attitude. The consumers’ motivation may differ from business to business and may not be identical in an industry. Reliability of the data is the outcome of a series of actions that commence with the proper explanation of the issues to be resolved. This may push on to a clear recognition of the yardsticks concerned. It contains the target samples to be chosen, the proper sampling strategy and the sampling methods to be employed.

A research methodology is an arranged method to push to increase new information. In Research Methodology, the scientist dependably tries to seek the research question deliberately in a particular manner and figure out every one of the answers until the conclusion. On the off chance that the examination does not work deliberately on the issue, then there is less probability to figure out the last result. For discovering or investigating the research questions, a scientist confronts a parcel of issues that can be adequately determined by utilizing the right research methodology (Saunders, Thornhill & Lewis 2009).

Results and Discussions

Introduction

This section covers the analysis of the data, presentation, and interpretation. The results were analyzed using SPPS, ANOVA, regression, and correlation analysis.

Reliability Analysis

Reliability analysis is often used to evaluate whether the multiple instrument items are measuring the same variable or concept. In SPSS, the Cronbach’s Alpha value is normally used to measure the reliability of the various variables. The minimum requirement for the value of Cronbach’s Alpha is 0.7 to ensure that the items are internally consistent and reliable. In the exploratory study, Cronbach’s Alpha value of 0.6 can also be accepted. In this study, the various measurement items are adopted from previous studies, thus, the minimum value is set at 0.7. The corrected-item total correlation (CITC) is also included to evaluate the reliability of the individual item. If the CICT is below 0.5, then the item cannot reliably measure the corresponding variable and should be excluded from further analysis.

Table 4.2 Reliability Analysis for Variables.

According to the results, the Cronbach’s alpha value of Functional diversity, deep level diversity, mutual trust, knowledge sharing, communication quality, cultural adaption, and virtual team effectiveness are 0.836, 0.817, 0.761, 0.739, 0.898, 0.833, and 0.837, which are all above the minimum requirement of 0.7. Besides, the CICT for individual items is all above the minimum requirement of 0.5, and the Cronbach’s Alpha, if deleted for individual items, are all below the Cronbach’s Alpha value. These results demonstrate that these items are internally consistent and reliable, and can be used for further analysis.

Frequency analysis

Functional diversity frequency analysis

Table 4.3. The functional diversity frequency analysis.

As can be seen from Table 4.3, more than half of the participants are familiar with functional diversity. There are 52.1% of the participants indicate that “Members of the team are similar in terms of their functional expertise” and 46.2% of the participants indicate that “Members of the team are similar in terms of their educational background”. From the total score of these 3 items measuring functional diversity, a large group of participants has a score of 11 or 12. To gain a clearer picture of the participants’ functional diversity, the items measuring functional diversity were aggregated. The aggregated mean value was 3.69, suggesting that participants have medium level functional diversity.

Deep level diversity frequency analysis

Table 4.4 Deep level diversity frequency analysis.

Table 4.4 shows the overall responses to the deep level of diversity among participants. According to the results, the mean value of all measurement items was between 3 and 4. Thus, the participants’ attitude, concern was at a medium level. By analyzing the frequency, it can be seen that more than half of the participants have expressed their concern regarding the level of diversity. To gain a more detailed picture of the level of deep-level diversity, the aggregate mean score was classified into three levels: low (below 2), medium (2-4), and high (4-5). The aggregate mean score was 3.76, suggesting a medium level of deep-level diversity. The overall scores of the items measuring deep level diversity were summarized, and it is found that the range was 16, with scores ranging from 5 to 20. The majority of the participants have an overall score between 14 and 16.

Mutual trust frequency analysis

Table 4.5 Mutual trust frequency analysis.

Table 4.5 summarized the frequency analysis for items measuring mutual trust. According to the results, the majority of the participants agree or strongly agree that “Team members in this team are considerate of other’s feelings”, “Team members can rely on fellow team members”, and “Members in the team are trustworthy”. The aggregated mean value of mutual trust is 3.98, nearly 4; suggesting that participants have a positive attitude towards mutual trust.

Knowledge sharing frequency analysis

Table 4.6 Knowledge sharing frequency analysis.

Table 4.6 summarized the frequency analysis for items measuring knowledge sharing. According to the results, more than half of the participants agree or strongly agree that “Members in this team share work reports, methodologies, and official documents within the team”, “Members of this team share their functional experience and know-how within others on the team”, and “Members of this team share their knowledge from education or training with other members of the team”. The aggregated mean value of mutual trust is 3.85, suggesting that knowledge sharing is at a medium to a high level. As can be seen from the results, the majority of the score ranged between 10 and 13, which also indicate a medium to high-level knowledge sharing perception.

Communication quality frequency analysis

Table 4.7 Communication quality frequency analysis,

Table 4.7 summarized the frequency analysis for items measuring communication quality. According to the results, more than half of the participants agree or strongly agree that “There is frequent communication between team members”, “There is timely communication among team members”, and “There is accurate communication among team members”. The aggregated mean value of communication quality is 3.79, suggesting that the communication quality is at a medium to a high level. As can be seen from the results, the majority of the score ranged between 18 and 22, which also indicate a medium to high-level communication quality.

Cultural adaption frequency analysis

Table 4.8 Cultural adaption frequency analysis.

Table 4.8 summarized the frequency analysis for items measuring cultural adaption. According to the results, less than half of the participants agree or strongly agree that “Cultural adaption is a natural and timely process in the team”, “The company provides cultural training for team members”, “Team members try to adapt to each other’s working style”. The aggregated mean value of mutual trust is 3.53, suggesting that the cultural adaption is at a medium level. As can be seen from the results, the majority of the score ranged between 10 and 11, which also indicate medium level cultural adaption.

Virtual team effectiveness frequency analysis

Table 4.9 Virtual team effectiveness frequency analysis.

Table 4.9 summarized the frequency analysis for items measuring virtual team effectiveness. According to the results, nearly half of the participants agree or strongly agree that “In the past, the team has been effective in reaching its goals”, “Completion of work is generally within the assigned budget”. The aggregated mean value of mutual trust is 3.52, suggesting that the cultural adaption is at a medium level. Figure 4.13 summarized the score of the items measuring virtual team effectiveness. As can be seen from the results, the majority of the score ranged between 10 and 11, which also indicate medium level virtual team effectiveness.

Correlation analysis

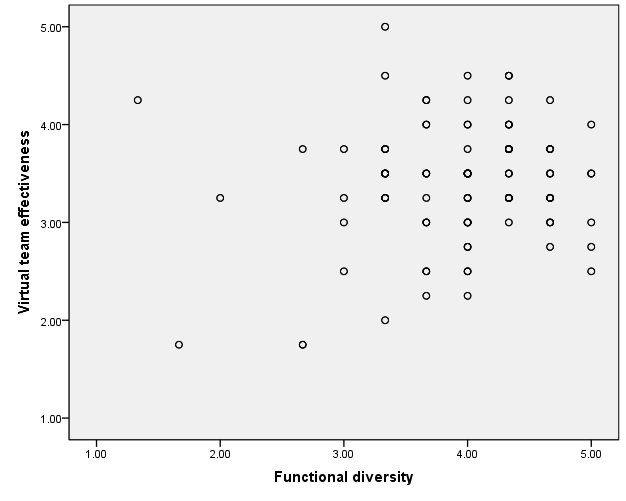

Correlation between Functional diversity and Virtual team effectiveness

To check the correlation between functional diversity and virtual team effectiveness, a scatter plot was first created to ensure that there was not a violation of the assumptions of normality, linearity, and homoscedasticity among the data. As seen in Figure 4.1 below, there is a strong, positive correlation between the variables of Functional diversity and virtual team effectiveness, and the data is normally distributed.

After inspecting a positive correlation between functional diversity and virtual team effectiveness, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was carried out to analyze the relationship between Functional diversity and customer virtual team effectiveness. The correlation value below 0.3 indicates a low-level correlation; the correlation value between 0.3 and 0.6 indicates a medium level correlation, while the correlation value above 0.6 indicates a higher-level correlation. As can be seen in Table 4.10, there was a medium positive correlation between functional diversity and virtual team effectiveness, with a correlation value of 0.373, which is significant at 0.01 levels, indicating that higher levels of functional diversity are associated with higher levels of customer virtual team effectiveness.

Table 4.10 Correlation between functional diversity and virtual team effectiveness.

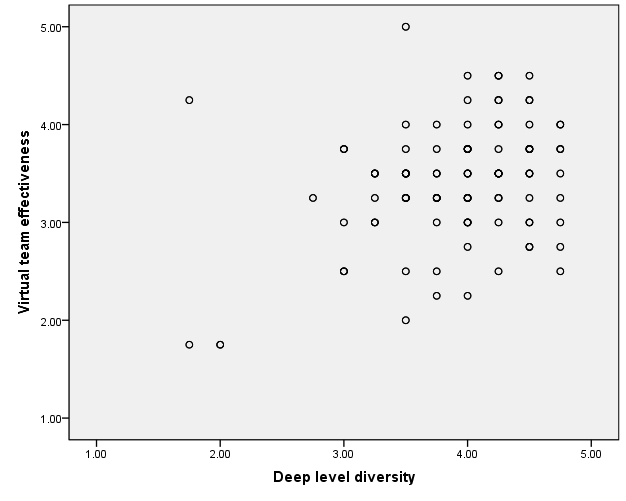

The correlation between deep-level diversity and Virtual team effectiveness

To check the correlation between Functional diversity and virtual team effectiveness, a scatter plot was created. As seen in Figure 4.2 below, there is a strong, positive correlation between the variables of deep-level diversity and virtual team effectiveness, and the data is normally distributed.

After inspecting a positive correlation between deep-level diversity and virtual team effectiveness, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was carried out to analyze the relationship between deep-level diversity and customer virtual team effectiveness. The results are shown in Table 4.11 below. As can be seen in the table, there was a medium positive correlation between deep-level diversity and virtual team effectiveness, with a correlation value of 0.313, which is significant at 0.01 level, indicating that higher levels of deep-level diversity are associated with higher levels of customer virtual team effectiveness.

Table 4.11: The correlation between deep-level diversity and Virtual team effectiveness.

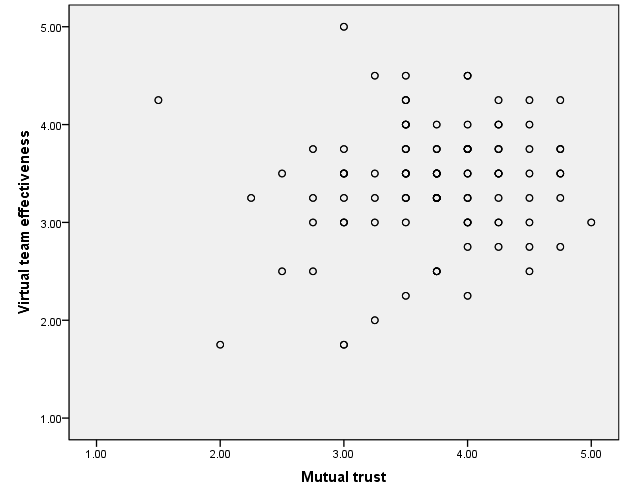

The correlation between Mutual trust and Virtual team effectiveness

To check the correlation between a fair wage and virtual team effectiveness, a scatter plot was created. As seen in Figure 4.3 below, there is a strong, positive correlation between the variables of mutual trust and virtual team effectiveness, and the data are normally distributed.

After inspecting a positive correlation between a fair wage and virtual team effectiveness, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was carried out to analyze the relationship between mutual trust and virtual team effectiveness. The results are shown in Table 4.12 below. As can be seen from this table, there was a medium positive correlation between mutual trust and virtual team effectiveness, with a correlation value of 0.412, which is significant at 0.01 level, indicating that higher levels of mutual trust are associated with higher levels of customer virtual team effectiveness.

Table 4.12 Correlation between Mutual trust and Virtual team effectiveness.

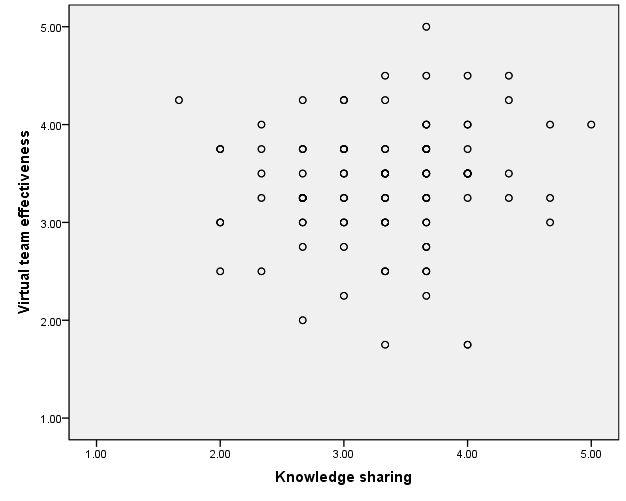

The correlation between knowledge sharing and virtual team effectiveness

To check the correlation between knowledge sharing and virtual team effectiveness, a scatter plot was created. As seen in Figure 4.4 below, there is a strong, positive correlation between the variables of knowledge sharing and virtual team effectiveness, and the data is normally distributed.

After inspecting a positive correlation between knowledge sharing and virtual team effectiveness, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was carried out to analyze the relationship between knowledge sharing and customer virtual team effectiveness. The results are shown in Table 4.13 below. As can be seen from this table, there was a medium positive correlation between knowledge sharing and virtual team effectiveness, with a correlation value of 0.409, which is significant at 0.01 level, indicating that higher levels of knowledge sharing are associated with higher levels of customer virtual team effectiveness.

Table 4.13 Correlation between knowledge sharing and virtual team effectiveness.

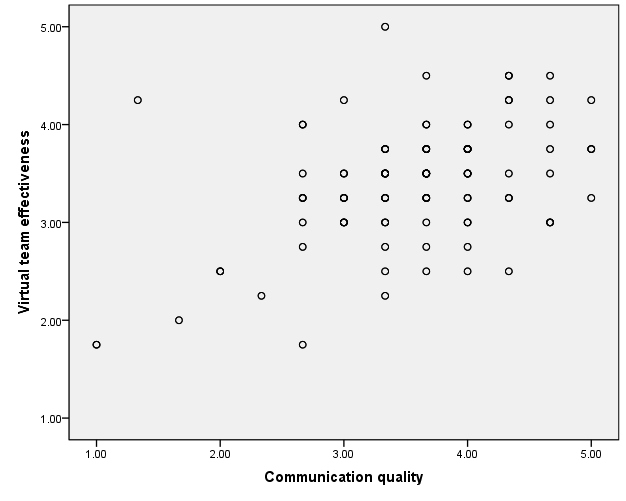

Correlation between Communication quality and Virtual team effectiveness

To check the correlation between communication quality and virtual team effectiveness, a scatter plot was created. As seen in Figure 4.5 below, there is a strong, positive correlation between the variables of communication quality and virtual team effectiveness, and the data is normally distributed.

After inspecting a positive correlation between communication quality and virtual team effectiveness, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was carried out to analyze the relationship between communication quality and customer virtual team effectiveness. The results are shown in Table 4.14 below. As can be seen from this table, there was a medium positive correlation between communication quality and virtual team effectiveness, with a correlation value of 0.455, which is significant at 0.01 level, indicating that higher levels of communication quality are associated with higher levels of customer virtual team effectiveness.

Table 4.14 Correlation between communication quality and virtual team effectiveness.

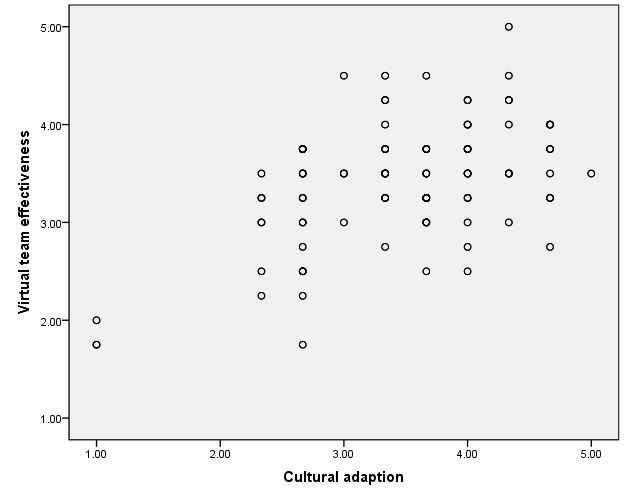

The correlation between cultural adaption and virtual team effectiveness

To check the correlation between cultural adaption and virtual team effectiveness, a scatter plot was created. As seen in Figure 4.6 below, there is a strong, positive correlation between the variables of cultural adaption and virtual team effectiveness, and the data is normally distributed.

After inspecting a positive correlation between cultural adaption and virtual team effectiveness, a Pearson product-moment correlation coefficient was carried out to analyze the relationship between cultural adaption and customer virtual team effectiveness. The results are shown in Table 4.15 below. As can be seen from this table, there was a strong positive correlation between cultural adaption and virtual team effectiveness, with a correlation value of 0.765, which is significant at 0.01 level, indicating that higher levels of cultural adaption are associated with higher levels of customer virtual team effectiveness.

Table 4.15 Correlation between cultural adaption and virtual team effectiveness.

Regression analysis

Regression analysis is a statistical process for estimating the relationships among variables (Blanchard & Cathy, 2002). More specifically, regression analysis is normally used to understand how the change of independent variables can affect the change of dependent variables (Blanchard & Cathy, 2002). The correlation analysis above indicated that there are relationships between cultural adaption, communication quality, Functional diversity, mutual trust, knowledge sharing, deep level diversity, and virtual team effectiveness. To find out how these variables influence customer virtual team effectiveness and which one has the biggest impact, multiple-linear regression is used.

Table 4.16 Model Summary.

The Adjusted R Square is 0.536, which means that the independent variables of cultural adaption, communication quality, Functional diversity, mutual trust, knowledge sharing, and deep-level diversity can explain 53.6% of the variance of virtual team effectiveness.

Table 4.17 ANOVA.

By summarizing the ANOVA table, it can be said that the independent variables of cultural adaption, communication quality, Functional diversity, mutual trust, knowledge sharing, and deep-level diversity can predict the dependent variable of virtual team effectiveness at a significance of 0.01, by considering F=411.961.

Table 4.18 Coefficients.