Architectural Principles

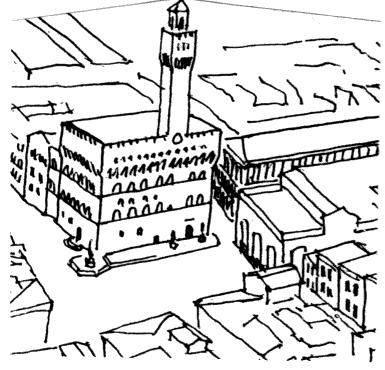

According to Bleek and Hinze (2000), the architectural principles used in the design and construction of Piazza Annunziata and Palazzo della Signoria vary significantly because of the difference in the purpose for which they were intended and the designers. For instance, the final building that is known as Palazzo della Signoria, which is also referred to as the Palazzo Vecchio was successfully build after three design stages between the 13th and 16th centuries. The main construction of the main building started at the Arnolfo’s palace next to the Loggia dei Lanzi and was later modified by Vasari, after coming to power in the late years of the 15th century (Burckhardt 1987).

Pythagoras theorem

The architects who constructed the Palazzo della Signoria used different principles some of which were based on the theories of corrective thinking such as the use of ratios to communicate or share information. Some of the examples of the principles that were applied include the Pythagoras theorem and the stoical principle of internal speech. Trachtenberg (1988) argues that the principles formed the foundation of architect that was used to express the internal geometry of buildings, which changed the qualitative understanding of numbers.

Typically, it was Piazza Del Duomo who designed the plan and other views that were used to build Palazzo della Signoria based on the principle of the triangulation of vision. Here, the projecting corners of the Palazzo della Signoria reinforced the oblique view of the structure, which consisted of corners that were at 90° subtended at 45° from a viewer’s side to the apex of the belfry (Nevola 2007).

It is evident from the study that the visual effects created by the geometry used to design the Palazzo della Signoria were the result of medieval optics. However, it is important to conclude that there were other people who made minor contributions to the knowledge used to design the structure besides those mentioned in this study (Marina 2012). For instance, Roger bacon made contributions on how optics to measure the distance between two corners and the angular distance between corners using geometric forms, space and views that were consistent with the geometric principles of medieval optics.

Ratio and views

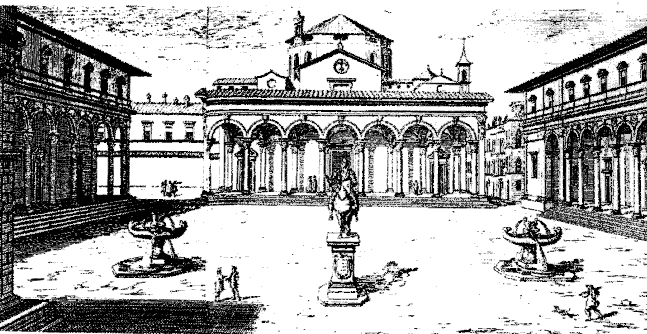

On the other hand, the Piazza Annunziata is an architectural design that provides a description of the proper use of town space for setting up buildings in public places (Horváth 2011). Here, Piazza Annunziata is a building with a small rectangular space that has a back that was used as the plan to build the house, which approximates to a perfect square. The designers used the principle of ratios to express distances as ratios, where the ratio of the short direction of the back of the piazza to the effective height was 1:3.3, and the ratio of the piazza in the long direction to the height was 1: 5.4. However, the ratio of the distance between the back of the piazza to the direction towards the cathedral was 1: 3.8 (Canniffe 2012). An investigation of the relationship between the ratios and the architectural principles of designing and constructing buildings shows that the ratios were within the ideal range advocated by Alberti the architect (Horváth 2011).

However, an inspection of the other sections shows that the vertical viewing angle of the hospital that formed part of the Piazza Annunziata was 18° from the ground which was presumed to be the correct angle that could provide the best enclosure. On the other hand, the viewing angle of the Piazza Annunziata from the direction of the hospital was 60°, which theorists contend to be the best angle that provides the best enclosure of the piazza. The issue is that the piazza was supposed to maintain the best visual structure that could show an effective architectural design and composition of the building.

The Piazza Annunziata demonstrates the use of the simple architectural elements of the piazza structure that consist of arcs and columns that unified the theme of the work of many artists for many centuries. It is evident that three of the corners of the building were open while the outlets were narrowed to make it difficult for the eye to wonder beyond the space that was enclosed by the piazza structure.

It is evident from the design and composition of the elements used to construct the piazza that the views were created by use of the ideal distances that were necessary to make the views clear for one who wanted to see the piazza from different directions.

Principle of the second man

On the other hand, the existence of the building is based on the principles of the second man, which states that the first man can only be created or destroyed at the discretion of the second man. The principle of the second man typically set in motion the process of completing the civic design by later architects and artists when those who designed the piazza were not there.

On the other hand, the design principles that were evidently used to create the framework used for the construction of Piazza della Santissima Annunziata include the Foundling’s Hospital, which is an example of the renaissance architecture that had the patterns used to design the piazza. This is a beautiful and elegant building that consists of columns and elements that are arranged in a symmetrical pattern. The building also consists of the hall of the confraternity, an enlarged porch, and a spatial unity of the ensembles.

On the other hand, the Piazza della Signoria consists of a medieval appearance with a subordinate space north of the Palazzo. Here, the interplay of different points on the space occupied by the formal facade with completely organised design decomposition meets the eye when making entry into the piazza. On the other hand, the view from the northeast of the piazza provides the viewer with a detailed design of the building and the narrow streets that occur between the equestrian figure and the figure of the Neptune.

In addition, the drama of living is intensified by the architectural design that creates spaces for buildings and people to occupy as in the case of the Uffizi that were designed and developed by Arno. Here, the principle of the recession plane is clearly demonstrated in the shaft of space contained in the Uffizi walls and the arch at the point where the arch terminates its links with the plane that points towards the cathedral.

Civic Principles

The civic principles that were applied in the construction of the two pizzas can be explained by the use of the renaissance spatial theory that formed the crucial foundation for the construction of piazzas in many urban areas in Italy. Typically, the architects who constructed Piazza Annunziata and the Palazzo della Signoria in the renaissance period relied on different components such as the line of sight for their urban design work (Fanelli, Hautmann & Mazza 1999).

The components were used to design the structures that could give the urban designers the ability to create different city interiors such as enclosed spaces and primary streets among others. It is argued that the structures that resulted from the use of the renaissance theory do not conform to the classical principles of design. For instance, Piazza Annunziata was constructed using the principles that make it appear to be a formal and conscious unified volume. On the other hand, Piazza della Signoria is described as an L-shaped square that reflects the government of medieval renaissance that existed when the town was constructed at the center of the original town of Florentia between the 13th and 14th centuries. On the other hand, the Piazza Santissima Annunziata was constructed to provide views that could make one get the feeling of one who is entering the Kingdom of God. Here, when entering through the entrance to the parvis exchequer gate, one could get the view of the Piazza Santissima Annunziata that made one have the feeling of entering a palatial place.

Communities

It is important to note that both piazzas were developed in communities and areas that were the subject of production and subjectivity. Typically, it is important to note that subjectivity was defined by the cultural aspirations of the people, the symbols represented by the structure, and the rituals of the people. For instance, the Piazza della Signoria was defined by Florentines who could enter and use the piazza through different routes which led into the square where benches were positioned in the open spaces for the people to use when they wanted to engage in parody and play.

Symbols and meaning

It is argued that symbols sometimes do not express meaning but provide the people with the ability to make meaning. When symbols are used to analyse the Piazza della Signoria, it is evident that the piazza is a practiced place rather than a passive site. In the context of the civic principles used at the time, the piazza is a viewed as an icon of popular guild based republicanism that embodied the virtues of popular assembly and open government (Flanigan 2008).

Here, the piazza was viewed as a civic icon because of the ideological dimensions and enshrined legal principles of the Roman legal system. It is the piazza that formed a place where the dignitaries of the town could come to the town for political participation before mass gatherings in the main civic area. It is important to note that the political participation of the dignitaries was done in the public square that consisted of a raised platform on the northern façade. The construction of the façade transformed the relationship between the piazza and the palace by making it to mediate between the internal and the external views of the piazza. On the hand, it is possible to see that some sections of the piazza consisted of a detailed fine massive sculpture and interlaced arcading with low resolution that was caused by the twin towers lying in the structure. In addition, the Piazza Santissima Annunziata lacked the dominance of the features that were distinct of a door, but the defect in composition did not deny the structure the richness of the rhythm is portrayed (Horváth, G 2011).

Typically, Piazza Santissima Annunziata represents the standards of the renaissance and urban landscape. In addition, the symbolic meaning of the structure is embodied in the symmetrical arrangement of the arcade that faces the hospital.

Shared spaces

It is critical to note that the construction of the Piazza della Signoria was based on the civic principles that allowed the architects to create space for bridges and walls and to add shared spaces such as streets under the principle of the publication of urban space (Cox-Rearick 1993). The spatial recognition of urban space and the creation of communal space formed the foundation upon which the piazza was shaped. However, there was a strong link between spatial and political reordering of the piazza, which demonstrated the symbiosis that existed between the two elements. The civic principles were based on the inspiration of the duke who wanted to construct the piazza as a fortified defensive bulwark.

On the other hand, Piazza Santissima Annunziata consists of fortification designs, new districts, extended streets, and new towns. The symbolic meaning of the city was demonstrated in the stimulated interest in military engineering of an ideal city (Cox-Rearick 1993). However, the spaces within the city existed as roads functioning as visual links to those monuments and buildings within the city.

References

Bleek, U & Hinze, P 2000, Florence-Fiesole, Prato, Pistoia, San Gimignano, Volterra, Siena: An Up-to-date Travel Guide;[with Fold-out Map]. G. Nelles (Ed.), Hunter Publishing, Inc.New York.

Burckhardt, J 1987, The Architecture of the Italian renaissance, University of Chicago Press, Chicago.

Canniffe, E 2012, The politics of the piazza: the history and meaning of the Italian square. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd, London.

Cox-Rearick, J 1993, Bronzino’s chapel of Eleonora in the Palazzo Vecchio (Vol. 29). Univ of California Press, California.

Drisin, A 2004, Intricate Fictions: Mapping Princely Authority in a Sixteenth-Century Florentine Urban Plan. Journal of Architectural Education, vol. 4, no. 57, pp. 41-55.

Flanigan, T 2008, The Ponte Vecchio and the Art of Urban Planning in Late Medieval Florence. Gesta, 1-15.

Fanelli, G, Hautmann, A & Mazza, B 1999, Anton Hautmann: Firenze in stereoscopia. Octavo.

Horváth, G 2011, Rephrased, Relocated, Repainted: visual anachronism as a narrative device. Image & Narrative, vol. 4, no. 12, pp. 4-17.

Marina, A 2012, The Italian piazza transformed: Parma in the communal age. Penn State Press, Pennsylvania.

Nevola, F 2007, Siena: constructing the Renaissance city. Yale University Press, Yale.

Trachtenberg, M 1988, What Brunelleschi saw: monument and site at the Palazzo Vecchio in Florence. The Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians, vol. 1, no. 1, pp. 14-44.